Home » Firearms and Shooting » Shotguns » Rise of the Over-Under Shotgun: A History Lesson

Rise of the Over-Under Shotgun: A History Lesson

- This article originally ran in the Fall 2020 issue of the Project Upland Magazine.

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's…

The rise of the over-under and a history lesson in fashionable shotguns

Do you think of yourself as fashionable? Probably not, and most of the bird hunters I know would agree with you. For us, fashion is a four-letter word and as appealing as watching Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

But that doesn’t mean we’re immune to fashion-like whims.

Like any group, we have things that are in (Gunner Kennels), things that are out (beeper collars), and things that were out but are now kind of in (smoking a pipe—I guess). We have hip gadgets (Garmin fēnix watches), trendy dogs (Wirehaired Pointing Griffons), and fads (34-inch barrels). For several decades now, the over-under has been the double-barrel for us to carry. In fact, O/Us are so popular that until about a decade ago, new, affordable side-by-sides ceased to be sold in the United States. Today, a few are around; but compared to over-unders, the total numbers hardly matter. In the grouse woods, on skeet fields, and across sporting-clay courses, if you’re shooting a double, you’re shooting an O/U. As one gunmaker told me in 2019, “the side-by-side is dead.”

A hundred years ago, side-by-sides were built by hundreds of makers. Some cost less than a good week’s wage, like the Belgian-made “Highly Engraved Diana Style Breech Shotguns” sold by Sears. Others, like an extra-finish pigeon gun from James Purdey & Sons, cost more than a new house. Back then, over-unders were around, but they were scarcer than ruffed grouse are today in New Jersey.

So what happened? Where did all of today’s O/Us come from? Compared to side-by-sides, are they any better? Or are over-unders just—you’ll die if it’s true—fashionable?

“Bagh… ” my friend Art barked. “ …whoever told you that’s a fool.”

We were in his basement, leaning against his workbench, about to look over an old but new-to-him Purdey O/U. He was taking it out of its leather case piece by piece when I had asked him if over-under shotguns were a 20th-century thing.

“There’s absolutely nothing new about over-under shotguns,” Art said. “People have been making them as long as they’ve been making guns. I’ve seen percussion O/Us, flintlock O/Us. And, sure as shit, someone was building O/Us before that, probably in Italy or Germany.”

He took the Purdey’s barrels in one hand, and snapped them into the action, attached the forend, and passed the gun to me with both hands. Art always held onto a gun for a moment when he handed it to me, like he was trying to remind me just how precious it was.

“Woodward patented that shotgun in 1913.”

“But it says Purdey,” I pointed out, looking at the J. Purdey & Sons engraved on the lockplates amidst the swirling scrollwork and bouquets of roses.

“Yeah, Purdey bought Woodward’s design after World War II,” Art continued. “They made some tweaks to it, but essentially it’s the same gun.”

“Woodward came out with their O/U four years after Boss. That’s when O/Us were the hot, new thing in London. The story goes that Robertson . . . ”

“Robertson?” I asked.

“The guy who made Boss into Boss. Before him, it was just another London gunmaker. Robertson made it the king. Some O/Us showed up in London, and Robertson saw one of them. Merkel over in Germany was making O/Us around 1900, so it must have been one of those. Robertson saw one and, being a clever son-of-a-bitch, thought ‘I can do better—and make money doing it.'”

“But you said O/Us had always been around?”

“Yeah, but for whatever reason, those older designs never went anywhere. They were probably a pain-in-the-ass to build and or too much trouble to use. I think Greener built an over-under hammer gun in the 1880s. I know Dickson built a few hammerless ones around that time. They opened to the side. Strange things. None of those designs went anywhere. As far as I know, Merkel was the first outfit to really make a go with these guns.”

Art walked away, leaving me at the workbench with the Purdey. I could hear him upstairs when the floorboards above me creaked. He appeared minutes later with another O/U. “This is a Merkel, from the ’30s,” he said, setting the gun down on the workbench. “It’s a sidelock—like the Purdey—but totally different.”

I could see what he meant. The action on the Merkel was taller than the Purdey, say four fingers compared to three, and the Merkel had a full pistol-grip stock and high vent rib.

“Look at this,” Art said as he broke down the Merkel and lifted the barrels free of the action. He pointed to two lumps sticking out from the bottom of the barrel, similar to what you would see on a side-by-side.

“Boss got rid of these,” he said. “Woodward did the same thing, but in his own way. That’s why my Purdey is trim like an English pointer and the Merkel looks like a fat Lab.”

Art’s introduction to O/Us spurred me to learn more about these guns. Along with Boss and Woodward, other British gunmakers came up with their own over-unders. Joseph Lang built a few and so did Holland & Holland. Beesley built a handful called the “Shotover,” while Westley Richards sold a model named the “Ovundo.” Hussey and Churchill made some using their own designs and others that were basically copies of a Woodward.

Up until World War II, Belgian and German gunmakers like Francotte, Greifelt, Heym, and Sempert & Krieghoff also made O/Us, everything from straight-gripped .410s for quail hunting to eight-pound 12-gauges for live pigeons and targets. None of these O/Us sold in big numbers. Some were too complicated, some were too cumbersome, and almost all were too expensive. In the ’30s, the best Merkel O/U, a gun called the Paragon, cost more than a Parker A-1 Special and as much as a Boss. And Boss O/Us cost more than most people made in a year.

I saw Art a few months later at our shooting club and joined him for some sporting clays. As we walked to the course, I mentioned how I had studied up on O/Us.

“Well, it’s about time,” he said. I rolled my eyes.

“But there’s one thing I don’t get. How did the O/U go from being something for the elite to being the gun every guy had? What made them popular?”

“I always figured it was Browning and his Superposed,” Art said as we reached station one. Then he stepped up to take a shot. The clay turned into a cloud of orange dust.

Even if you don’t know who John M. Browning was, you know his work. Browning invented everything from the lever-action rifles American settlers carried into the west to the machine guns American soldiers carried into World War II. More important to us, he patented the pump shotgun that became the Winchester Model 97 and the semi-auto that became the Browning A5 and Remington Model 11. With these firearms, he did more than anyone to kill off the double-barrel shotgun. Then toward the end of his life, he did more than anyone to bring them back.

While guns like the Winchester Model 97 and the Browning A5 lacked the style and elegance of a Parker or Fox side-by-side, they made up for it with something American shooters liked far more: firepower. The Model 97 held six shells; the Auto-5 one less. A hunter with one of these shotguns could blast through these rounds before a person with a side-by-side could fire two rounds and reload. This blazing speed attracted thousands of buyers right after pumps and semi-autos were introduced. But as time went on, it also attracted scorn.

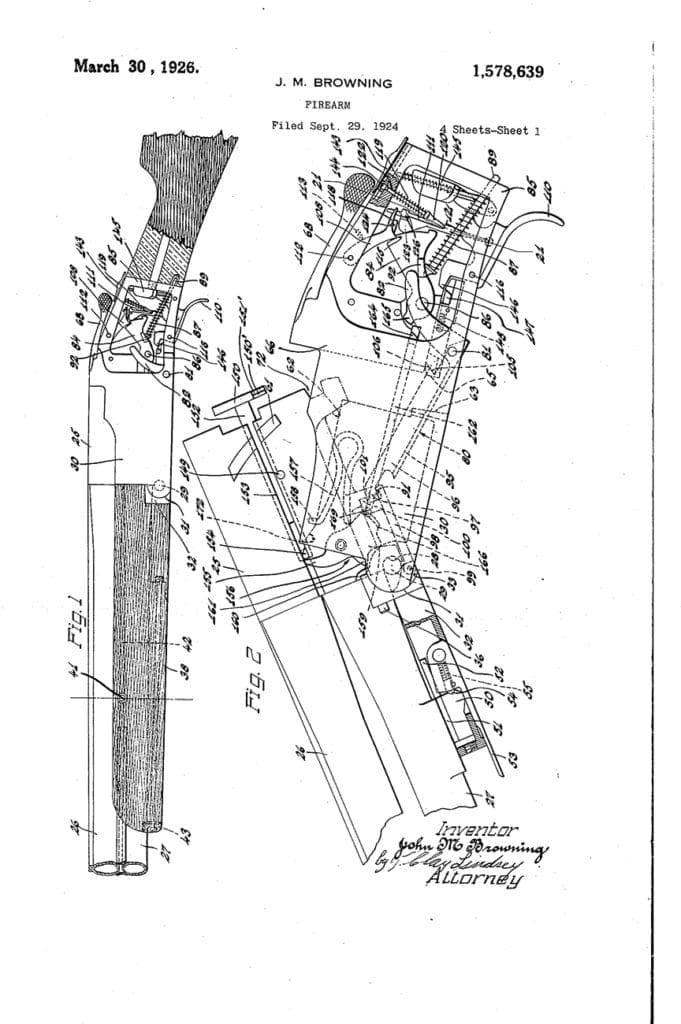

This contempt was a key reason John M. Browning created the Superposed, one of the most successful over-unders of all time. According to The Browning Superposed by Ned Schwing, “He (Browning) was concerned that the rising protest against repeating guns (conservationists called them game exterminators) would have an adverse effect on the sales of his previous semiautomatic designs.” Browning told his son Val, “I think there is a market for a reasonably priced over-under shotgun which will be one of the last shotguns to be legislated out of business.” Browning filed the first patent for his O/U in 1923, but he died before it could be perfected and built. His son Val carried the work, and in 1931, the first Browning Superposed over-unders went on sale in the U.S.

First over-under encounter

“What are those?” I said to my friend. I was 12 years old and standing in his living room. I had just spotted the wooden gun case in the corner by their television. It had frosted pheasants on its doors, and amber light shone down inside, giving the firearms it contained a holy luster.

“Those are my dad’s,” my friend responded. I walked closer and saw some rifles: a couple of lever-actions, a few pumps. Then I saw the O/U. “That’s his Browning,” my friend said, knowing what had caught my eye. He was as impressed with it as I was. We both stood there admiring it, knowing that doing anything more was not in our best interest.

My friend’s dad worked in the paper mill down the road, had a Brittany, and took weeks off in the fall to hunt grouse and woodcock. His 20-gauge Browning Superposed was a prized possession. When I was a kid, the Superposed was the kind of shotgun people aspired to own. It wasn’t cheap, but it was within reach of most people—even if they had to stretch to afford one. John M. Browning would have been thrilled to learn all this. He wanted the Superposed to be a high-quality, well-balanced gun that many Americans could afford. From the time it was introduced and into the ’70s Browning sold around 200,000 of them, proving that the Superposed was loved by hunters and shooters worldwide and that Browning’s original vision was prescient and right on.

Other players in the over-under game

I’ve always thought of ideas as being similar to radio waves. Even though they’re all around us, most of us don’t pick up on them. John M. Browning could and he used these ideas to develop the Superposed. But he wasn’t the only American receiving these signals. In the 1930s, other companies in this country introduced designs for O/Us, like the Remington Model 32, the Savage 420/430, and Marlin Model 90. On the other side of the Atlantic, Belgian and French makers such as Defourney, Lebeau Courally, and Pirlet came up with their spin on the stacked-barrel idea. But while some sold okay, none were game-changers like the Superposed. The first guns to stand nose-to-nose with Browning’s design came from Italy and a gunmaker few Americans knew a thing about.

Beretta created their first O/U in 1933. The Mod. S1. Fucile da Caccia Sovrapposta (the sexy way to say “over-under shotgun”) borrowed from British and German designs and featured sidelocks, a low-profile action, and double Kersten locks. Beretta followed up this gun with a boxlock version they called the ASE (Anson Sovrapposta Ejectore). The New York Times reviewed one in 1948 and reported: “It’s a beautifully balanced, light gun..” They also pointed out why the ASE would never take the place of the Superposed “…the prices charged put such guns beyond the reach of most shooters.” Beretta’s sidelock S1 had the same problem.

Beretta addressed this price issue in 1955 when they introduced the S55 (Silver Snipe), S56 (Golden Snipe), and S57 (Ruby Snipe). These O/Us combined features of the S1 and ASE with mass-production techniques. Compared to a Superposed, all the S55, S56, and S57 weighed less; the S55 and S56 cost less, too. Thanks to these differences, the Beretta’s S-line of O/Us sold well. Over time, these guns evolved into some of the best-selling O/Us ever, like the Beretta 686 and the S687 Silver Pigeon.

A few years after Beretta’s success in the United States, an Italian named Daniel Perazzi introduced an O/U of his own. Ennio Mattarelli used this Perazzi to win a gold medal at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo—the second time an Italian O/U had won Olympic Gold (Galliano Rossini did it with a Beretta in 1956). This proved that these new Italian shotguns were true contenders. Seeing an opportunity, the Ithaca Gun Co. started importing Perazzis in 1973. Americans won major competitions with these O/Us; Perazzi won a reputation for rugged, reliable target guns that seemed to give some shooters an edge.

From the 1960s and through the ’90s, Beretta and Perazzi introduced thousands of Americans to the merits of Italian-made O/Us. This cleared a path for other Italian gunmakers, including Zoli, B. Rizzini, Franchi, and Caesar Guerini. It also pulled the plug on the sick man of the gun world: side-by-sides. Demand for side-by-sides had been eroding since the 1920s. After World War II, it collapsed, and most of the American makers still building them went out of business or gave up on the style. Winchester made the Model 21 a custom-shop-only item in 1960, admitting that most shooters were not interested in its side-by-sides anymore. Stevens killed off their 311s and Fox Model Bs in the 80s. While other makers—including SKB, Beretta, and famous British names like Boss, James Purdey & Sons, and Holland & Holland—continued building side-by-sides, demand for these doubles was weak. For the Brits, it amounted to maybe a few hundred guns a year. The reality was this: If you wanted to sell double-barrel shotguns, the only real action was in O/Us. But why? Are they the better guns?

Is the over-under a better gun?

Magic is not something you expect to see on a trap or skeet field. But when I looked at the gadgets and oddities those shooters swear by (ported barrels, mercury recoil reducers, fluorescent barrel beads), I came away thinking that many of these “advantages” were really illusions. So let’s start with some genuine facts about O/Us:

- Over-unders are stiffer. They flex less up and down when fired, which helps you recover faster from your first shot and follow up with a quicker, more accurate second shot.

- Over-unders manage recoil better. They recoil deeper in your shoulder pocket, where your body has more meat. This extra mass does a better job of displacing shockwaves. It reduces felt recoil and makes O/Us more comfortable to shoot.

- Over-unders are easier to control. Because their forends are deep, they need to be cupped in your lead hand. At the same, most O/Us have pistol-grip stocks. These lock your rear hand in place and are more comfortable to hold. Together, these features give you more control of an O/U, making the gun more pointable.

- Over-unders have a single sighting plane. Look down an O/U and what do you see? A rib, a bit of a single barrel, and a bead. That’s it—and it’s a lot less than what you see when you look down a SxS. While this difference seems to be an obvious advantage, the first commandment of shooting a shotgun well is “Don’t look down the barrels.” If this is true, why does a single sighting plane matter?

Steve Rawsthorne of the Holland & Holland Shooting Grounds, quoted in a 2018 article in The Field, explains it this way: “While one should not be looking at the barrels during the shot, one needs to be aware of them in the peripheral vision while the central focus is on the target; the barrels of an over and under obscure less of the target and surrounding area.”

Fair enough.

So that’s four strikes against the side-by-sides. Are they out? Absolutely not. Side-by-sides have their advantages, and when it comes to bird hunting, some people think they’re the better gun. Here are three reasons why:

- Side-by-sides have a wide sighting plane. This can be beneficial. “One of the reasons side-by-side guns are easier for some people to shoot is that broad plane,” says Phil Bourjaily, Field & Stream’s Shotgun Editor. “Even though you’re not looking at it, it gives you a good point of reference—especially on rising targets like upland birds.”

- Side-by-sides are lighter…most of the time. If you’re carrying a shotgun all day, lighter is what you want. A lighter gun fatigues you less and comes to your shoulder quicker when it is time to shoot.

- Side-by-sides handle better for bird hunters. As just noted, side-by-sides are usually lighter than O/Us, especially in the barrels. This makes these guns feel livelier in your hands, so it’s easier to snap them to your shoulder and shoot them fast. Also, many side-by-sides feel lighter than they really are. That’s rarely the case with O/Us; in fact, most of them feel heavier than they are.

On top of these rational reasons to pick a side-by-side, there’s one that aims right at the heart: tradition. Many of the people who made upland hunting famous shot side-by-sides. Nash Buckingham hunted with an A.H. Fox, and so did the naturalist Aldo Leopold. William Harnden Foster, Burton L. Spiller and Bill Tapply all shot Parkers, while George Evans carried a Purdey and then an AYA. If your grandfather or great-grandfather were bird hunters, they probably shot a side-by-side, too. When you carry a similar shotgun into the field, you join them in this history and turn a day of bird hunting into a link with the past and a richer, more meaningful experience.

Something else to consider: hunters have used side-by-sides for hundreds of years to kill plenty of birds. On the trap field or when shooting clays, the advantages O/Us offer may be the difference between winning or losing. But do these advantages matter in the field? Not really. Hunting isn’t about winning, and no one should judge the success of a the day solely by the number of birds killed. If the stock on a side-by-side fits you and you shoot the right loads, you should be able to take plenty of game birds.

Perhaps more people are realizing all this about side-by-sides. That may explain why the market has seen a resurgence in demand for these guns in the last few years and why that gunmaker I mentioned at the beginning of this story has changed his mind about side-by-sides. In 2019, he said they were dead. In February of 2020, he showed me the new side-by-side his company was hoping to launch in 2021.

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's been interested in shotguns and gundogs since he was a kid. Today, he blogs about both at www.DogsandDoubles.com and posts to Instagram @dogsanddoubles

Great article. I definitely need a SxS 28ga.

Glad you liked it. Thanks for the comment.

Gregg

http://www.DogsandDoubles.com

I absolutely love my Pedersoli 12 bore sidexside muzzle loading shotgun. Love it.

Sxs have a single “sighting plane” as well, as you covered, albeit wider. Still just one rib. Also, a ton of people go from a single shot, or pump to a O/U. The “picture” is similar when transitioning to a O/U. I’ve found that in the SxS vs OU debate the difference is negligible on flushing birds. But the less obscured view from ou’s on true crossers is noticeable.

Solid article.

Glad you liked it. Thanks for the comment.

Gregg

http://www.DogsandDoubles.com

I completely understand why people like SXSs. My first shotgun at the age of 13 was a SXS as were my next two shotguns. Along the way I acquired another 3 SXSs while at the same time owning several O/Us. Now I have no SXSs. I just found that I shoot better with an O/U. What I don’t like about shooting a SXS is that one has to place the left hand (assuming one is right handed) on the bare barrels. Well, that is the way I was taught to shoot. I was told at an early age that the forearm on a SXS is there just to hold the barrels on the receiver. The beavertail forearm on some American models being a bit of a joke to me.

Of course this can uncomfortable without a glove or guard. Why bother? O/Us have a forearm that you can hold while shooting.

As far as weight goes, I have owned Beretta S3s, aka, SO3s, that weigh less than 7 pounds. I don’t think SXS have any practical weight advantage. How light does anyone really want a 12 gauge?

The one advantage other than esthetics with SXSs is that SXSs are easier faster to reload in the field.

I am fond of double triggers and straight grip stocks in a field gun, a personal choice. I like how the straight grip carries and like the racy looks. I am not sure why I like double triggers. Maybe because my first gun had them. Of course this changes with a target gun. Then it’s pistol grip and a single trigger.

I tried a sxs when younger and could never find that second trigger with a gloved hand. That’s why I prefer the o/u which only has one trigger

In the beginning of the article you put out the possibility that the O/U was a fad. Yet, in today’s market you can get good O/U for a much lower price than good side by side. I have wanted a good side by side for years now. Not because it is a better gun. But, because it is cool. I have friends that feel the same way. If anything the side by side has become the fab as of lately.

Hey there Gregg, sending greetings from NYC. Excellent article–thanks for writing it. My wife started shooting my 20ga SxS this past summer and really preferred its sighting plane, perhaps because of her cross eye dominance. Another advantage she discovered was the shallower break of the SxS, which made for easier reloading (something I had always commented on, but she never fully appreciated). As a person smaller in stature, she liked the slim forend and the straight grip, both of which fit her hands better. She also actually liked the second trigger, because it slowed down her second shot. The only problem is now I have to let her use it. Until we get her one for herself.

Hope you and your dogs are doing well and looking forward to some time in the field in the new year!

Thanks, Ray. I hope you and your wife have been doing some hunting this fall. Great to hear from you.

Gregg

Good article,…although I ll take my “ trendy Griff” over the spastic GSPs and Vizslas my buddy’s use any day o week .

I have had the opportunity to hunt with individuals who have SxS with double triggers. They are able to choose choke and shot before pulling the trigger. If you can do that you have an advantage.

Great article and very balanced. In the end its nice to have the choice. I mostly shoot a 1974 AYA XXV sideplate. A 25″ barrelled side by side shotgun is currently about as unfashionable as shotguns get and as such can be bought second hand for peanuts. Yet, it still shoots straighter than I can, it is totally at home on our shoot (quite wooded) as well as on long walked up grouse days on the moors (where it is easy to carry broken over a forearm without its barrels dragging in the heather!) It is a beautiful piece of engineering that I enjoy looking at and looking after (hopefully) for the next generation. Here’s hoping the shooting industry soon develops a cost effective alternative to steel shot so that these older, great value and still effective shotguns can remain in use. For the sake of balance I also have O/Us – a browning fn superposed and a beretta silver pigeon – but rarely shoot these outside of the clayground as I don’t feel quite the same connection on shoot day. For me shooting game with my SBS just feels a bit more special than with my O/U, perhaps I am more thoughtful when shooting it. Perhaps to me it feels more flyfishing than spinning! Thanks again for the great article.

One of the best arguments for the English SxS game gun (whether produced in the UK, US, or Europe) I’ve read, is a quote by author Stephen Bodio: “Why kill a beautiful bird with an ugly gun?”