Home » Hunting Dogs » History of Richard Purcell Llewellin

History of Richard Purcell Llewellin

A.J. DeRosa, founder of Project Upland, is a New England…

The story of the iconic man behind the debated Llewellin Setter legacy.

Speak the words “Llewellin setter” and you are bound to be met with controversy. On one side are the devoted bird hunters who count themselves among the ranks of owners of a bloodline developed over 150 years ago, while others will say there is no difference between an English setter and a Llewellin. Before that and worthy of a deep dive in itself was the setting spaniel, regarding which the father of the English Setter, Edward Laverack, would comment that “the setter is but an improved spaniel.”

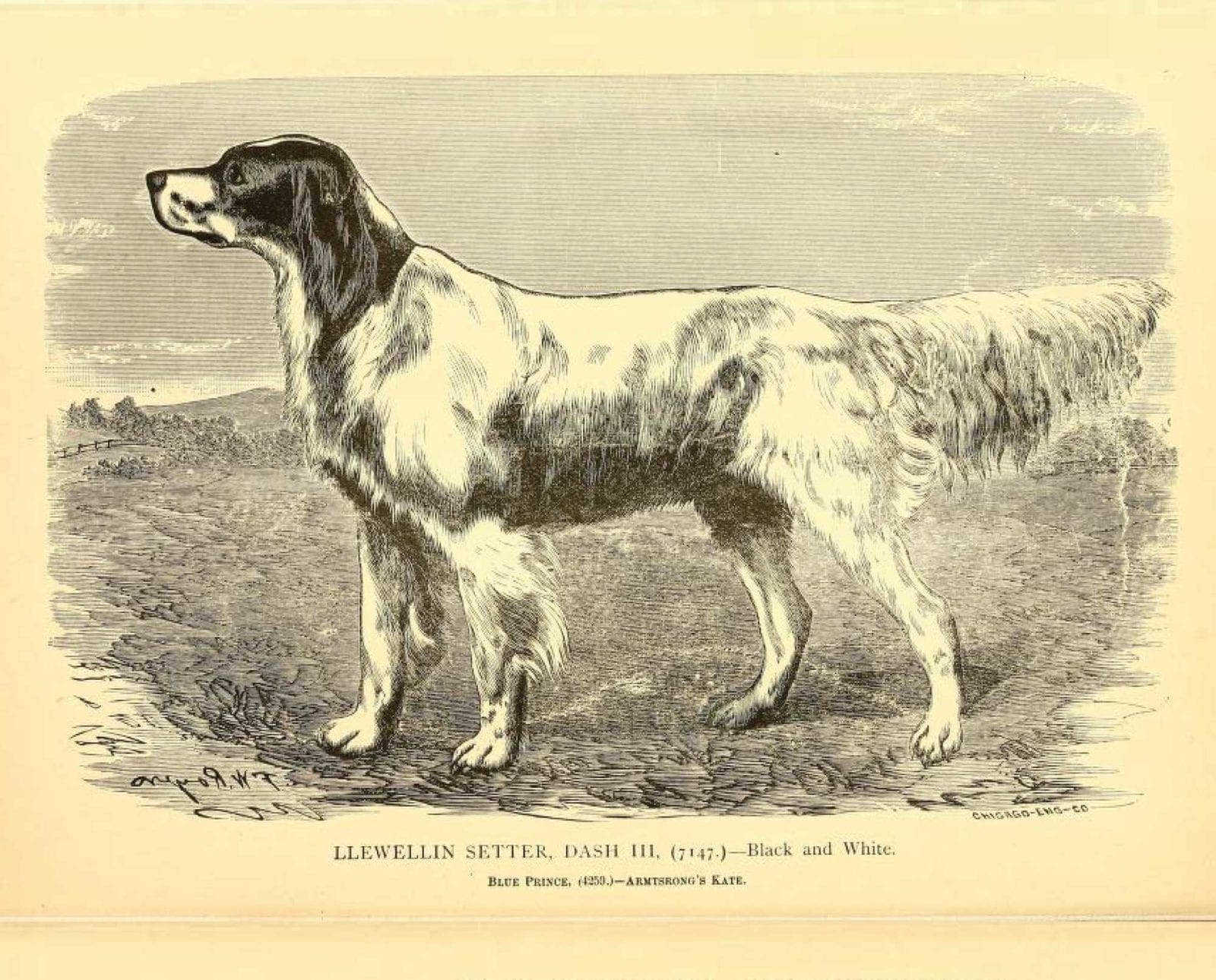

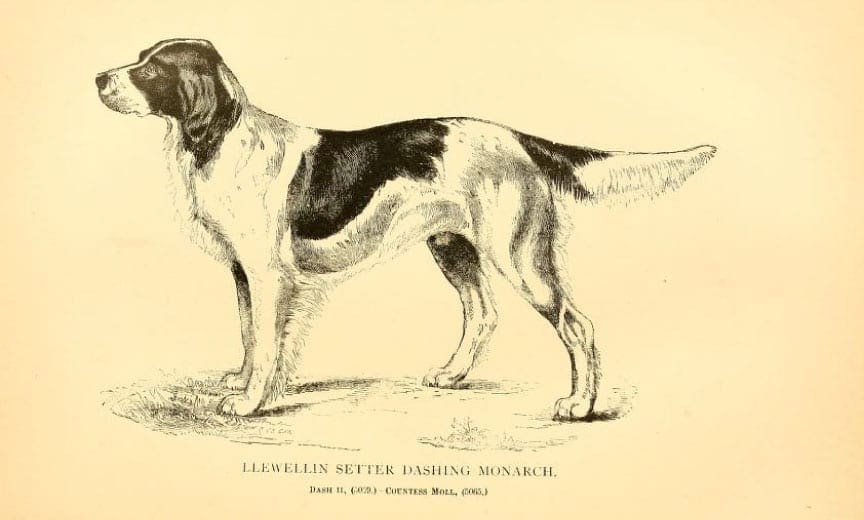

Here we’ll explore the factual history as has been recorded as far back as the first book written on the modern setter in 1872 by Edward Laverack himself, The Setter, which incidental to this story was dedicated to R. LL. Purcell Llewellin, and of whom Laverack refers as one “who has endeavored, and is still endeavoring, by sparing neither expense nor trouble, to bring to perfection the ‘setter.’”

It’s important to first note the importance of Edward Laverack as he appears in the story as the founding father of the modern setter. His line of Laverack setters had taken on the English field trials by storm, but he nevertheless felt that Richard Llewellin was the one to carry the breed to the next level. Laverack’s dogs were used in the development of the Llewellin line. They would also play critical roles in other famous bloodlines like the Ryman setter.

The background of R. LL. Purcell Llewellin

Born in 1840 in South Wales, Richard Purcell was born into a wealthy family as every story begins in the development of European hunting dogs. In the 1870s he added the surname Llewellin to his name in order to inherit his grandfather’s estate (on his mother side). This was crucial to his breeding campaign as it gave him ample freedom to pursue the idea and only fitting that it became the Llewellin setter.

Laverack had created a breed that was based on beauty and form and Llewellin took the idea of a field dog to the next level. In the plainest sense, Richard Llewellin’s goal was to create a very good hunting dog by not focusing on the ideas of a show ring. He represents a distinct splitting point: dogs imported to the United States to begin the pursuit of the Llewellin setter, and a line that stayed in the United Kingdom. Both were set on creating good pointing dogs, both paths having very different standards on what defines a good hunting dog. This becomes a theme for the Llewellin setter and flip flops over time on what defines a good bird dog.

Is a Llewellin setter different than an English setter?

This question is a slippery slope. In the case of debates like the difference between the Deutsch-Drahthaar and a German wirehaired pointer, it all comes down to breed standards as set forth by club standards. The German system requires standards of testing before breeding as well as different physical standards than the AKC (American Kennel Club) uses to define a German wirehaired pointer. In this regard, the Llewellin setter begins to lose ground and shows the real difference in the AKC and its regulation of breed standards.

More than anything the Llewellin setter is based on an idea of a bird dog that is bred to hunt in a certain manner, one that has changed with the times. The AKC and in this case the English Setter Association of America (ESAA) maintain breed standards based on physical appearance and not performance. Their goal is to maintain the purity of the breed by blood. Some argue that because of the popularity of Llewellin’s dogs, just about every modern English setter in the United States has their blood. Some claim the opposite.

This is not a new debate. The argument ensued as early as the 1880s over whether or not the Llewellin was a distinct breed. In his book The American Kennel and Sporting Field written in 1883 by Arnold Burges, the author points out a rift that arises in the story of the Llewellin setter very early. Through staunch arguments in the community of English setter breeders there was a claim that the Llewellin was no different than the Laverack setter. He also points out in the publication The Field, May 20, 1882, “It is idle to say that Mr. Laverack created a breed whereas Mr. Llewellin has only taken advantage of materials readily made. Even Mr. Laverack himself admits that he obtained his Adam and Eve from a friend and simply bred from them.”

The final debate rests in the fact that Richard Llewellin’s dogs were consistent winners of field trials to a level never seen before, whereas the Laverack bloodline rested on the legacy of older dogs which had not produced any consistent winning offspring.

In the book The American Hunting Dog – Modern Strains of Bird Dogs and Hounds, and their Field Training, written in 1916 (reprinted in 1919) by a former editor of Field and Stream, Warren Miller, he points out a clear cultural shift that occurred when the English setter was introduced to the United States. That culture was the idea of southern quail plantation style hunting. As Americans, we created the idea of “Llewellin” representing a good quail dog in the English setter line. The book points out that many modern “Llewellin” bloodlines had none of Richard Llewellin’s pedigree. And to improve the performance of this new American idea of a good quail dog, breeders used English setters from Lavarack dogs and other English setter bloodlines. This was supported in the A.F. Hochwalt book, Dogcraft, originally published in 1907.

Horace Lytle, another Field and Stream editor, took it a step further in 1928. In his book How to Train Your Bird Dog, Lytle stated that “Llewellin Setters are nothing more – and nothing less – than English Setters. Llewellin Setters are simply English Setters that trace back to two particular English Setters. They represent a certain definite English Setter ancestry. That’s all there is to it. Thus an English Setter may not always be a ‘Llewellin,’ but a ‘Llewellin’ is always an English Setter.”

One can then argue that the idea of a Llewellin setter in the United States is, according to Miller, a dog “bred for generations for fast wide-ranging work,” preferred traits of southern trial culture. In contrast, he states “for grouse and all close covert work the English or Laverack setter will give him better satisfaction as he is closer to English forebears used to that kind of shooting.” Interestingly enough, there are kennels and groups that would point to “close working” as a definable trait of a Llewellin setter.

The Llewellin setter in America today

In essence, Richard Llewellin’s purpose and definition has been lost to the times, but the bloodline descendants are a different case. Many kennels claim to breed Llewellin setters and are based in the American cultural sense–which is the smaller 35 to 50-pound dogs, have high stamina, and work well in heat. Even that definition could be met with criticism. However, the distance factor seems to have evolved the most in American culture for the Llewellin setter. What was originally based on big working quail trial dogs has now been defined by some as close working grouse dogs.

One could quickly argue that a lot of this had to do with a rapid decline in quail hunting in the United States. The popularity of grouse dogs is still increasing, even as public access and ruffed grouse hunting, although declining, is still very much alive in the states.

The viability of claims of breeders having pedigree going back to Richard Llewellin’s dogs themselves is something that would certainly take due diligence to confirm and prove. In 2001 a 501(C)(3) called the North American Llewellin Breeders Association was formed. After some research it appears the organization may no longer exist, their website down and material not readily found on the internet.

The best definition of what a Llewellin setter would simply be is a good hunting-bred English setter not meant for a show ring. It is the only consistent standard throughout its history, and as we all guess plenty of people have different ideas on what defines a good hunting dog. Many parts of American culture are taking their idea and running with it.

The field dog stud book and the direct Llewellin setter bloodline

Now many can certainly debate what Richard Llewellin’s true intentions were in creating a hunting breed of English setters; unlike the German testing system, no clear performance standard was left behind. Which as mentioned above has left the definition of a “good hunting dog” open for interpretation. But no matter what we debate, there are in fact clear bloodlines that can be traced back to his breeding program.

The Field Dog Stud Book which has been published since 1874 recognizes a bloodline of Llewellin setters separate from the English setter. This is probably the most legitimate claim to dogs that have direct decendents to Richard Llewellin’s breeding program. Kyle Warren of Paint River Llewellins on a Project Upland Podcast episode points out how despite this being the case there is a real threat of the breed going extinct because of a lack of breeding pools. The records show a clear line going back to two specific dogs owned by Richard Llewellin himself, Duke and Rhoebe.

We must understand the history of these two dogs to get the clearest picture of what a Llewellin setter was in the time of their creation. Rhoebe is the most interesting part of this story. Half of her was Gordon Setter (at the time, all setters including Gordon and Irish were yet to be fully separated from the breed), and the other half a now long-gone strain called the South Esk. Two dogs came of the Rhoebe and Duke litters known as Dan and Dick. They were then bred back to two Laverack dogs that Richard Llewellin owned. That offspring represents the epitome of what he was trying to create and there are breeders that do in fact have clear history to that combination.

What should you look for when buying a Llewellin setter?

The greatest advice I’ve ever heard when it comes to getting a bird dog is making sure you select a gun dog for what you plan to do. Going to hunt ducks and need retrieving skills? Do not buy a pointer. Plan on hunting multiple species from rabbit, waterfowl, to upland? Get a versatile breed.

So, it should be said if you hunt ruffed grouse in grouse country, do not buy a dog breed to hunt quail. If you plan to hunt quail, do not get a dog bred to hunt ruffed grouse. Since many kennels in the United States want to debate whether a Llewellin setter should hunt big or close, it’s as simple as getting what works for you. Ask to hunt over those dogs before making that decision. People can claim all sorts of things a bloodline is capable of, but until one sees it with their own eyes, we must do due diligence in things like accolades. It’s as simple as experiencing their abilities firsthand.

There have been many attempts to prove lineage to true Llewellin setters and there is no doubt that some of these accounts are true. But we must consider how is this provenance confirmed? And that still begs the question: does the Llewellin label matter as some people throughout the history of the breed would debate their blood to either exist in all modern English setters and in other cases, none. At the most fundamental core is the question: what is a Llewellin setter in the definition of performance? The debate that ensues shows that there are many opinions on that definition, and there are dogs today with blood from Richard Llewellin’s setters that perform on two very opposite ends of the spectrum, the quail dog and the grouse dog.

The more I dove into this story the greater I found what the Richard Llewellin legacy is. It’s a concept of a breed; it is an English setter that is set to the highest standard of a good hunting dog. That concept has been achieved in many English setters, for many different applications. And with 100 plus years of breeding, the Llewellin setters of today are far more refined than some of the dogs of the past. The pursuit of the best dog through the ages is what the Llewellin setter story truly is.

A.J. DeRosa, founder of Project Upland, is a New England native with over 35 years of hunting experience across three continents. His passion for upland birds and side-by-side shotguns has taken him around the world, uncovering the stories of people and places connected to the uplands. First published in 2004, he wrote The Urban Deer Complex in 2014 and soon discovered a love for filmmaking, which led to the award-winning Project Upland film series. A.J.'s dedication to wildlife drives his advocacy for conservation policy and habitat funding at both federal and state levels. He serves as Vice Chair of the New Hampshire Fish & Game Commission, giving back to his community. You can often find A.J. and his Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, Grim, hunting in the mountains of New England—or wherever the birds lead them.

I have two Llewellyn’s from the Alford King line. Both dogs hunt close. Both dogs pointed and backed naturally with no training! I had one previously in the early seventies. All three are or were great friendly hunting dogs that live in the house!

Hi

I would like to know where did you get your two Llewellins breed from? Thank

I’ve had 3 English setters over my life time.

I have trained each dog to hunt pheasants.

The male setters are more independent and take more effort to train when young. My last English setter Buster lived to 15. He would point the bird and move then hold in different positions around the bird without busting out the bird.

What I notice is the lavrick type is taller and more slender than lewelin style.

Great dogs who love to please and love to hunt.

Training is key and continuous with this type of dog

About a year and a half ago I picked up a King-Lyon Llewellin from NC, where the King line is now based. He compliments my female Gordon well hunting Greater Sage Grouse in Wyoming. The Gordon runs medium to big, the Llewellin runs tight, and backs the Gordon well. He also visually checks every 50 yards or so, looking for the Gordon, for birds in flight, and for me. That’s been the most interesting aspect, as this article leaves out the falconry roots of the Llewellin’s early days. As my Llewellin + Gordon team hunts with my falcon, it’s truly an interesting dynamic. I’ve now completed the full circle, and crossed the Llewellin with the Gordon as was done in the early days pre-King James. Excited to see how the Llewellin/Gordon cross pups do on Sage Grouse with falconry.

The problem with lewellins is King himself.He improved the Lewellin only to loose their registry and ability to compete for the US National champion field trial.Today they are merely hunting dogs,dispute the fact that Count Noble won the first US National field trial and is mounted in a glass exhibit at the National Bird Dog Museum in grand junction TN.

BAD BUSINESS

I’ve been a die-hard ruffed grouse hunter for nearly forty years, and all of my Llewellin Setters have enjoyed documented lineage to the kennels of Sir William Humphries and Richard Purcell Llewellin. Every one of my Llewellins located and pointed ruffs from as young as ten months old. No “whoa” or backing training, the only commands I’ve taught are “come here”, “sit”, “heel”, “fetch”, and “kennel.” Their pointing instinct is, at least to me, remarkable – rarely, if ever, crowding their birds, and holding them until the flush. They learn their craft very quickly, and I love their style and intensity. All my Llewellins have naturally adjusted their distance to their environment, hunting wide in open areas, and close in a forest. While I appreciate the attributes of larger, closer and slower working setter strains, in every outing where I’ve worked my Llewellins with them, my dogs have run circles around them, and found most of, if not all, of the birds. For me, there’s nothing like watching a Llewellin setter work, whilst carrying an English game gun. To better understand the Llewellin setter and what the British aristocracy sought and desired in their pointing dogs, I recommend Derry Argue’s book Pointers & Setters, and any of Mr. Argue’s video productions.