Home » Hunting Dogs » Gun Dog – The Evolution and Definition of Modern Dog Breeds

Gun Dog – The Evolution and Definition of Modern Dog Breeds

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

The history of gundogs and firearms are intertwined as the development of one fueled the development of the other

Strictly speaking, once you have named a distinct group of dogs as “gundogs,” their history begins with the invention of firearms. But hunters were “armed” long before the introduction of firearms, with the spear, the bow and arrow, the boar-lance and the bolt-firing weapons to the fore… Before the invention of firearms, hunters were reliant on dogs which could indicate unseen game and not run-in, as well as those which could retrieve valuable bolts, especially from water, when used on wild fowl.

David Hancock

Hunting dogs are as old as the hills and guns have been around since the 1300s, but the idea of hunting with dogs and guns together didn’t really catch on until nearly two centuries after firearms first appeared on the battlefield. And even though the words dog and gun both trace back to the 14th century1, they weren’t combined to form the term “gundog” until the mid-1700s, nor did “gundog” become part of the common vocabulary until the mid-1800s.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION for FREE Google | Apple | Spotify

Early history of hunting with dogs

Prior to the invention of firearms, if a hunter wanted to shoot game instead of netting it, snaring it, or using a hawk or dog to catch it for him, he’d use a bow and arrow, stone bow, crossbow, or spear. But he’d want to find slow-moving or stationary targets to shoot, since hitting a running or flying target with a rock or arrow is extremely difficult. Even after the advent of sporting firearms in the 15th century, hunters continued to focus on stationary targets because early “fowling-pieces” required the shooter to use some sort of rest. Worse yet, if the gun was pointed even a few degrees above horizontal, the priming powder tended to slide out of the pan. So the best kinds of dogs for a hunter armed with a bow, an arquebus, a blunderbuss, or any other kind of early firearm were dogs that could help him find game—without causing it to flush or run away—or dogs that would retrieve anything he managed to hit, especially if it fell into water.

That is why the very earliest illustrations and descriptions of hunters working with dogs and guns together feature pointing dogs, retrievers, and water dogs. Other dogs like sighthounds, running hounds, and flushing spaniels were of little use to a hunter that wanted his quarry to stand still. Eventually, however, firearms became light enough and shooters became skilled enough to reliably hit swift-running deer, rabbits, boar, and even birds on the wing.

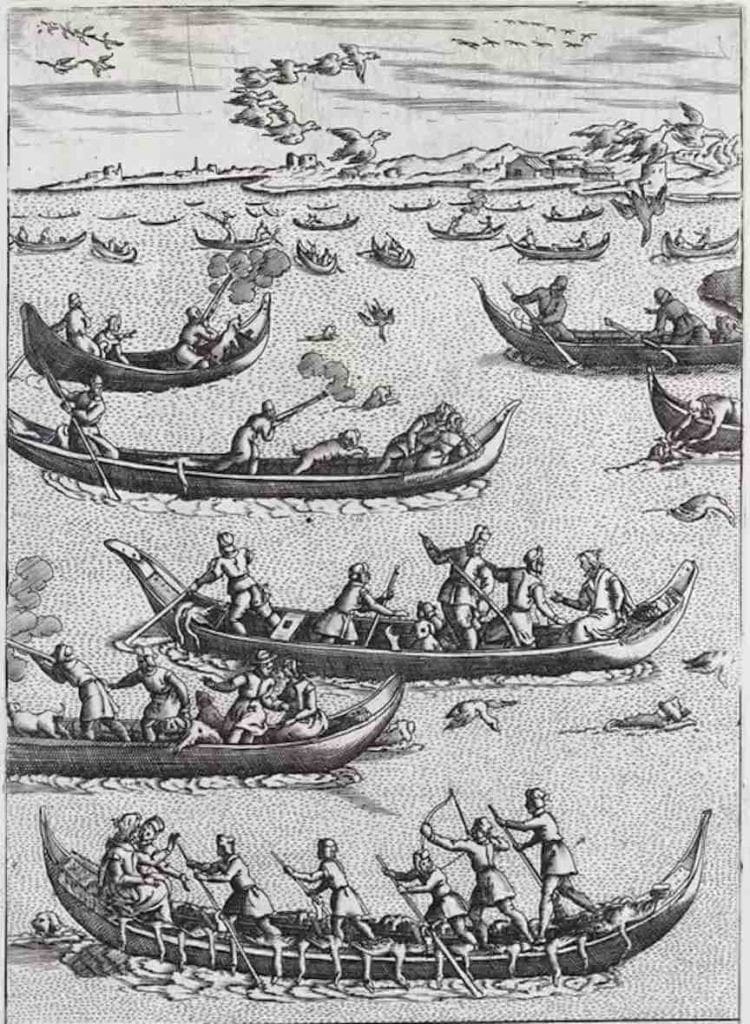

A fascinating example is an illustration found in the book Habiti d’huomini (Gentlemen’s Attire) written by Giacomo Franco in 1609. It is a detailed engraving from the transitional period in which many hunters were still using stone bows while others were trying their hand at the new art of “shooting flying.” The image depicts the nobles of Venice, some armed with stone bows and others with guns, shooting at birds on the water and in the air while dogs retrieve fallen birds.

Another example is from a manuscript published in 1644 in which the author, Alonzo Martinez de Espinar, laments the fact that because guns had become so easy to use and deadly on game, the art and skill of using dogs and crossbows was being lost.

Formerly when this sport was practised, the dogs were very clever and the men very scientific about it, and he who prided himself on being a sportsman shot over a dog so well-trained that, as the saying is, he could do everything but speak; and those that kept their dogs in food by the crossbow were always the most eminent, as the skill of the sportsman and his dog had to make up for the deficiencies of the weapon.

Alonzo Martinez de Espinar

Today, when one has no longer to shoot with a crossbow, no one remembers the craft the sportsman formerly possessed…..The partridges are shot with an arquebuse flying, and for that reason they do not exist in such numbers as formerly, nor are there any longer such pointing-dogs (perros de muestra) to find them and point them with cleverness so great that great quantities of them could be killed with a crossbow. In those days the sportsmen were most dexterous, now such are wanting; for, as the game is killed more easily, nobody wishes to waste his time in training dogs, as the man has not to shoot the partridges on the ground; and the only use he has for dogs is to flush the game, and that takes no training, as the dog does it naturally.

While Espinar is correct in stating that the training, hunting, and shooting skills required of a hunter armed with a crossbow would be lost, he overlooked the fact that new training, hunting, and shooting techniques were being developed to replace the old ones. Among them was something that every owner of a gundog does to this day: correctly introducing a young dog to gunfire. After all, a gun-shy dog isn’t much use as a gundog. So imagine a hunter—who’d been using dogs and crossbows for years—bringing out his fancy new “fowling-piece” for the first time. Did he just head to the field and hope his dog wouldn’t run off after the first shot? Did he ruin a few dogs before realizing that he had to get his pups used to the sound of gunfire? I don’t think that either would have been the case. Early adopters of firearms would have known the importance of making sure their animals were properly introduced to gunfire. After all, firearms were first used on the battlefield where soldiers used horses, oxen, mules, and dogs. So long before hunters began to shoot game over dogs, they would have developed methods to get them used to gunfire.

Developing gundogs to fit modern hunting methods

Another thing that changed when guns replaced crossbows was that dogs with greater speed, larger range, and stronger pointing instincts began to appear. A hunter with a gun didn’t need a dog to “circle” the bird anymore. He preferred a solid point, based on scent alone; he didn’t need to see the birds on the ground, since he could wait until they took to the air. And he no longer needed a dog to stay close, because he could kill a bird on the wing at 40 yards or more.

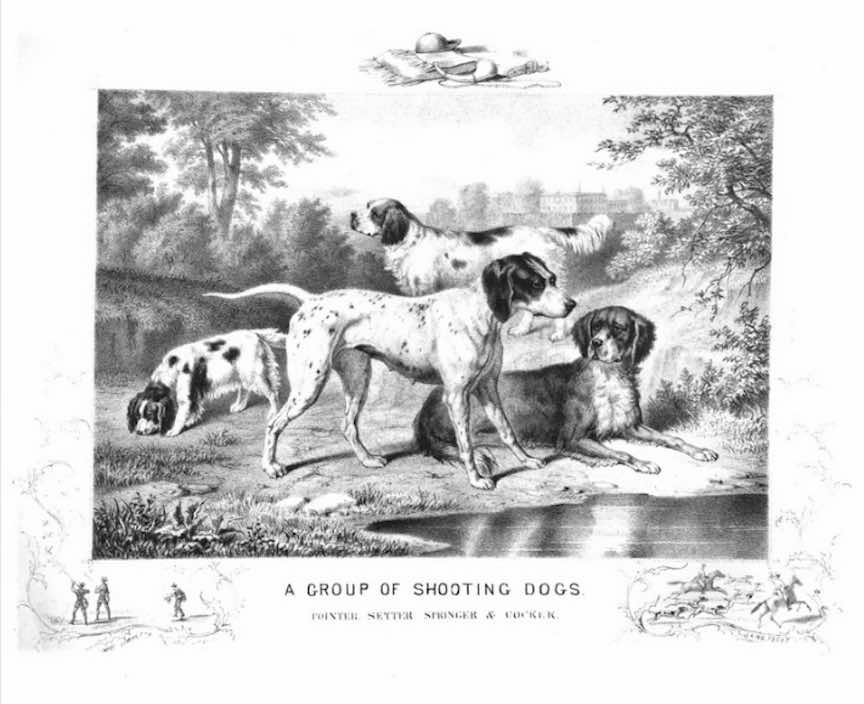

The concept of selecting and training dogs specifically for hunting with a gun began to take hold in 1700s, when English sportsmen imported short-haired pointing dogs along with the art of wingshooting from France and Spain. By the late 1700s, Pointers and “shooting flying” had become so popular that the term “gundog” was coined. At first it seems to have applied mainly to Pointers, Setters, and water dogs used for “fowling,” but it eventually came to mean any kind of dog used by hunters armed with guns.

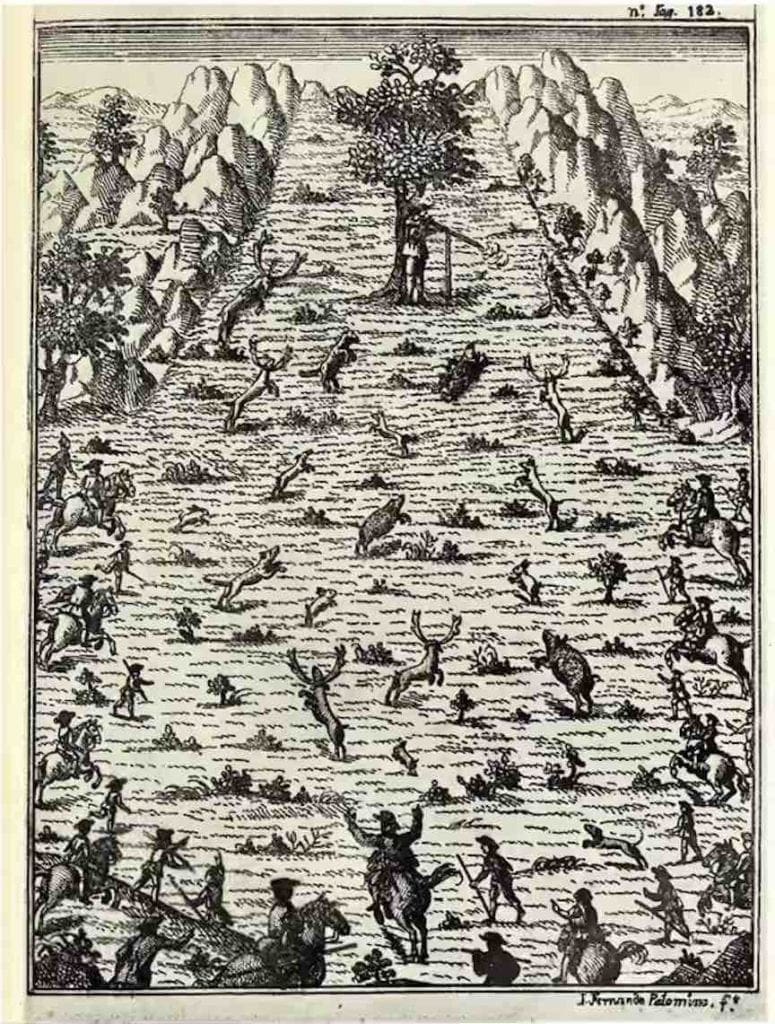

A drive of deer and wild boars in a mountain pass. The sportsman in the act of killing a fox stands against a tree and has a rest for his arquebus.

History of the term “Gundog”

Interestingly, the term “gundog” appears to be uniquely English. Other languages don’t have an equivalent compound word made up of gun and dog to describe these types of dogs. Most just use a general term like “hunting dog” or, if referring to a specific kind of hunting dog, terms like “bird dog,” “flushing dog,” or “pointing dog.” While there is a term in French chien de fusil (literally “dog of the gun”) it refers to the hammer (the chien) of a shotgun.

When the term was first coined it was most often hyphenated as “gun-dog.” Later on, the hyphen was dropped. In 1900, the term was so well-known that when the Retriever Society, the Pointer and Setter Society, and the Sporting Spaniel Society decided to amalgamate, they named the new organization The International Gundog League. When Great Britain’s Kennel Club reorganized their Division 1 Sporting Dogs and Division 2 into seven separate groups, they placed all pointing, flushing, retrieving, and a few water dog breeds into the newly formed gundog group. Today, of the 221 breeds recognized by the KC, 38 are in the gundog group. The Australian Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club also have gundog groups, but the American Kennel Club does not—they place pointers, setters, and retrievers in the sporting group, although they do run gundog stakes in some field trials.

Some of the terms used by gundog trainers and owners are directly related to the use of firearms, too. The most obvious is the now-obsolete “down charge” or “down to charge,” where a dog is trained to drop down and lay flat on its belly when a shot is fired. It reflects that fact that in the early days, it took a minute or more to reload a musket or muzzleloader, so training the dog to lay down when a shot was fired gave the shooter time to “charge” (load) his gun.

Every spaniel must be made perfectly steady at “down charge;” and until the gun is reloaded, not even the regular retriever must be allowed to move towards the wounded game.

The Shot-gun and Sporting Rifle: And the Dogs, Ponies, Ferrets, &c., Used with Them in the Various Kinds of Shooting and Trapping by John Henry Walsh, 1859.

Many persons, who otherwise take pride in breaking their dogs, frequently omit to teach them a most important accomplishment, or at least neglect to keep them to it after they have been taught. I allude to down charging. By want of attention on this point many shots are lost, especially in turnips and potatoes, where birds being dispersed, rise one or two at a time. The instant you fire, each dog should down, and not move again till you say “Hold up.” A dog I once had, always remained quiet till he heard the click of the lock preparatory to putting on the cap; this he took as a signal that all was right. Nine keepers out of ten neglect to teach their dogs to down charge. I cannot make out why such should be the case, but certainly so it is. I observed a short time since, as I rode along the road, two men—keepers I imagined them to be by their appearance—who were shooting. Each time they fired their dogs were on the move whilst they were loading. As it happened no birds were sprung, for the covey had all risen nearly together, but had there been any remaining the men would have lost the opportunity of getting shots.

American Farmers’ Magazine: Volume 2, Jan 1849, editor J. A. Nash

The shared history of gundogs and guns

It is also interesting to note that many of our modern gundog breeds were actually developed in regions known for gunmaking. The Bracco Italiano traces its roots to Lombardy, a region in northern Italy where some of the world’s oldest gun makers are still located. The French gun industry is centered around the city of St. Etienne in central France, which is also the ancestral home of the Braque d’Auvergne and Braque du Bourbonnais. In Spain, the same region that has produced guns for centuries also produced the old Spanish Pointer. In England, the first dog shows took place in Birmingham, one of the main centers of gun making in Britain. Early British field trials were sponsored by gunmakers who also bred and kept their own strains of Pointers and Setters. Even in the early days in America, centers of gunmaking like Pennsylvania and New York were also home to some of the country’s greatest gun dog breeders.

Today, the term “gundog” and the concept of breeding, training, and using dogs exclusively for hunting with a gun is universally understood. Sure, there are plenty of non-gundogs in use; in fact, some hunters choose sighthounds, podengos (warren hounds) or falconry dogs precisely because there are no guns involved at all. But for the vast majority of upland hunters (and, in some regions, big game hunters), the go-to dog is a gundog. Some hunters prefer big-running Pointers while others look toward dependable Labradors, energetic Cocker Spaniels, or versatile Griffons. But they are all gundogs, created to serve the gun and adapted to the tastes of the hunter carrying it.

1The word “gun” may come from the Old Norse word for battle, gunnr, or from Gunilda, a woman’s name given to a giant 14th century crossbow (Domina Gunilda, or “Lady Gunild”). The word “dog” traces back to the Old English word dogg, which is of uncertain origin.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

great contente

love this