Home » Hunting Dogs » Water Spaniels – Origins, Development and Modernization

Water Spaniels – Origins, Development and Modernization

Scottie Westfall is a native West Virginian who now lives…

Explore the fascinating history and evolution of water spaniels, from their origins in the British Isles to their close genetic ties with retriever breeds.

Water spaniels are but a vestige of what they once were. Originally developed in the British Isles for waterfowl retrieving, today only three breeds remain. The American Water Spaniel and its close cousin, the Boykin, are joined by the Irish Water Spaniel as remnants of what was once a broad spectrum of water dogs.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

The origin of water spaniels can be traced to Great Britain. Similar dogs were developed on the European continent, such as the Épagneul de Pont-Audemer or the Frisian Water Dog, but their exact relationship to the true water spaniels developed in the British Isles—and later in America—is not exactly clear.

What is clear is that a close relationship exists between water spaniels and the retriever breeds. Indeed, recent genome-wide analysis has revealed that the Curly-Coated Retriever and the Irish Water Spaniel are more closely related to each other than to any other breed. The Curly-Coated Retriever—the largest and perhaps oldest of the retrievers—is thought to have descended from crosses between the St. John’s Water Dog and English Water Spaniels, but apparently the amount of water spaniel blood in the breed was largely underestimated. Similarly, the Golden Retriever lineage that began with the Marjoribanks family in Scotland included crosses to at least two Tweed Water Spaniels.

English and Tweed Water Spaniels no longer exist, but their blood still flows through various retriever breeds and the remaining water spaniel breeds; it also may be found in land spaniels such as the English Springer Spaniel, which was likely derived from the Norfolk or Shropshire Spaniel. Depictions of this water spaniel show that it looked very much like an English Springer, just with a wild and wavy coat.

So, what happened to water spaniels that caused them to become so rare and, in many cases, extinct? It comes down to a combination of their use, maintenance, and the changing trends of hunting dogs in the twentieth century.

Origins of Water Dogs

The origin of water spaniels lies with water dogs, and the traditional European water dog was of a type that modern people would think of as “Poodles.” Russia, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and of course France all developed dogs of this type for waterfowl hunting. They were also used for the netting of fish, hauling lines and nets from the water, and—when crossbows were used for waterfowl hunting—they could even fetch crossbow bolts from the water. All of these dogs possessed a low- or non-shedding coat that needed to be regularly trimmed in order to allow the dog to swim efficiently, which is seen today in the traditional Poodle and Portuguese Water Dog trims.

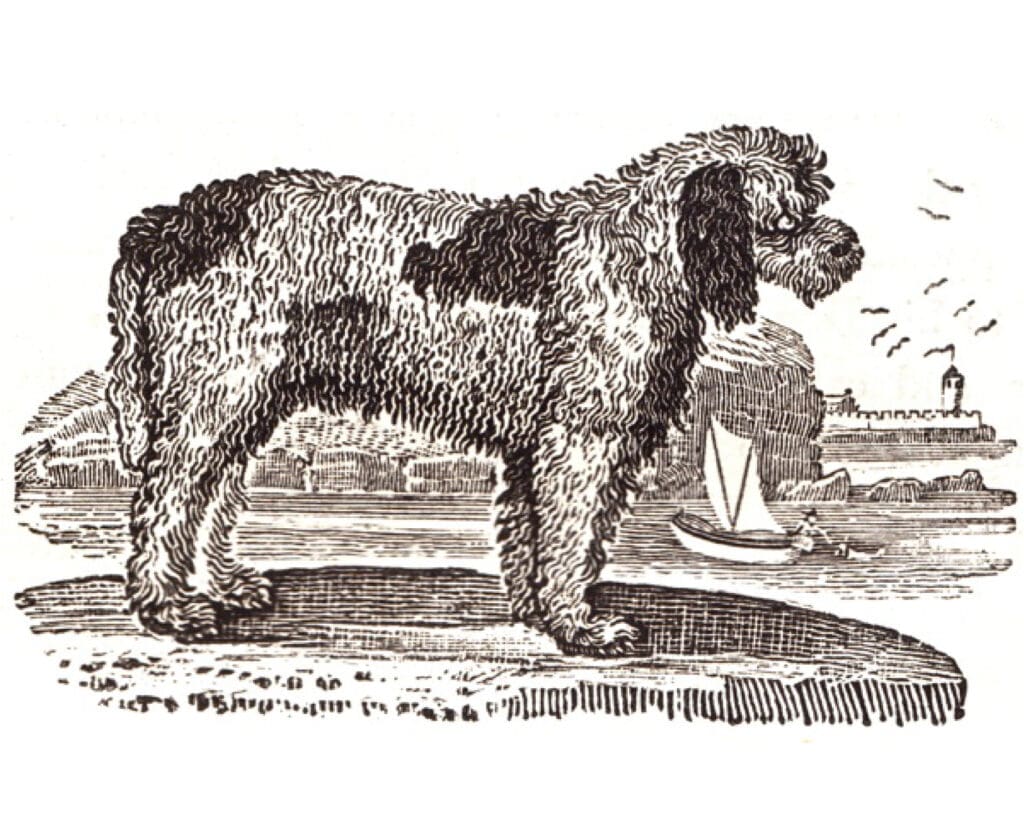

The British also had dogs of this type. In Shakespeare’s MacBeth, the titular character mentions “water rugs” as a type of dog that existed in England at the time. This “water rug” was the Poodle-type water dog of the British Isles. Thomas Bewick would later name this type of dog the “rough water dog” in his 1790 book A General History of Quadrupeds. Bewick describes the breed as having great utility in retrieving ducks and other birds from the water.

“From its aptness to fetch and carry,” writes Bewick, “it is frequently kept on board of ships, for the purpose of recovering anything that has fallen overboard; and is likewise useful in taking up birds that are shot, and drop into the sea.”

This dog served as the ship’s dog for most of England, but it was also widely used for duck hunting. Formalized duck shooting did not develop until the nineteenth century, but prior to that, having a dog of any kind that could fetch ducks could mean the difference between a meal and hunger. Ducks and other waterfowl were common along estuaries and rivers, and during times of hardship, the dogs proved their worth.

Development of Water Spaniels

Over the centuries, it became common to cross these water dogs with spaniels and setters. This cross added a certain amount of “birdiness” and also introduced a feathered coat. This coat type remains a recessive gene in today’s Poodle, as breeders of Goldendoodles know all too well. Today, if two first-cross Goldendoodles are bred together, they can produce puppies with the feathered retriever coat, although it is often wavier or curlier than a typical retriever’s coat.

By the early nineteenth century, the Poodle-type water dog that was native to England became absorbed into water spaniel strains. Half a century later, there were four breeds of water spaniels in the British Isles: the Irish Water Spaniel, the Northern Irish Water Spaniel, the Tweed Water Spaniel, and the English Water Spaniel.

Today’s Irish Water Spaniel retains much of the rough water dog’s coat, though its muzzle and tail are not as shaggy, and it does shed. It was largely developed by an Irish sportsman named Justin McCarthy. His exact story is not known, but McCarthy apparently spent time on the European continent, where he may have seen Barbets, the French version of the rough water dog. It is possible he used continental blood in his strain of water spaniels.

The Northern Irish Water Spaniel, on the other hand, was very much like a small, brown, Golden Retriever. Not much is known about the Northern Irish breed, but it is said that it was very similar to the Tweed Water Spaniel, which was developed in the Scottish Borders and in Northumberland. Because of the close cultural and historical connection between Northern Ireland and the Scottish Borders, it is very likely that the two strains were connected.

The Tweed Water Spaniel is well-known as being in the foundation of the Golden Retriever. It was known to have a bit of “Newfoundland” blood, which meant that it had St. John’s Water Dog ancestry. It was described as being like a Curly-Coated Retriever, just with a liver or yellow coat.

Stanley O’Neill, a celebrated Flat-Coated Retriever fancier, once saw a pair of these dogs on a salmon boat on the Northumberland coast. He was just a boy, growing fond of gun dogs in the late nineteenth century, so he attempted to show off his knowledge to the fishermen. He asked if the dogs were Curlies or “water dogs,” but the fishermen answered that they were Tweed Water Spaniels from Berwick. Berwick is the northernmost town in England and it is located on the River Tweed, which forms much of the border between Scotland and England. The Majoribanks family originated on the Scottish side and were familiar with the breed that they later crossed into their yellow retriever strain at their Highland estate.

Finally, there was the English Water Spaniel, which varied greatly in its appearance. It was a spaniel that took to water, but it could have collie or setter blood. It was of great utility for market hunters, who would send the dogs to fetch scores of ducks that were shot with punt guns. One shot from those cannons would drop whole flocks of ducks, so the hunter would have a nice profit for his labor.

Decline of Water Spaniels

As modern British shooting developed, water spaniels eventually fell from favor. True retrievers bred from the St. John’s Water Dog were more useful for the discipline of nonslip retriever work. These dogs were much easier to keep calm while shooting, and because patrician British shooters used land spaniels to flush game and retrievers to pick up, they began to reject the dual-purpose water spaniels.

Commoners, especially poachers and market hunters, relied upon water spaniels. Rawdon Lee, writing for the patrician dog fancier in his A History and Description of the Modern Dogs of Great Britain and Ireland (1893), excoriates the “ordinary brown retriever” that is one of heavy water spaniel ancestry. “He is usually snappish and ill-tempered,” writes Lee, “and when not looking in the gutters for a living may be found chained up to a kennel in someone’s back yard.”

Lee’s patrician sporting class preferred black retrievers of the St. John’s Water Dog type, not the brown dogs with water spaniel ancestry. Thus, his negative campaign was in keeping with the ongoing decline of water spaniels.

In the United States, Irish Water Spaniels were popular as retrievers well into the twentieth century. Irish immigrants particularly liked to use them for waterfowl, especially in the Midwest. It was from British and Irish Water Spaniels in Wisconsin that the American Water Spaniel was derived, and it is suspected that the Boykin Spaniel is at least partially derived from the American Water Spaniel. It is clear that both breeds have British and Irish ancestry. They are most similar to certain types of English Water Spaniel, specifically ones with a stronger spaniel influence and less of the rough water dog.

In the 1920s, formal retriever trials were introduced to the United States, as were British retrievers that had been derived from the St. John’s Water Dog: the Golden and Labrador Retrievers. The water spaniels were a poor fit for retriever trials, which required dogs that could handle lots of pressure to perform complicated retrieves. Further, the Labrador’s smooth coat was easier to care for and it dried faster after swimming in cold water.

For all of these reasons, breeds of water spaniel soon became rare. They were too spaniel-like to make it in the Labrador-dominated retriever trials, and they were too water-dog-like to fit into the world of spaniels. Further, because North Americans have little hesitancy to use retrievers as flushing dogs, retrievers would also become more common as flushing dogs than water spaniels.

The market hunter and the poacher needed a dog that could both flush and retrieve, which is why they favored the water spaniels. The modern sporting shooter in Britain preferred specialists, and Americans, who preferred to have flush and retrieve in the same dog, simply taught their Labradors to flush upland birds.

Water Spaniels Today

Today, the three remaining water spaniels maintain a devoted following. They are a sort of counterculture, working to preserve the abilities of dogs that the mainstream has otherwise passed by. The dogs are still useful and cherished, even though they exist in the gray zone between retriever and spaniel.

The spaniels of the marshes once had a great dynasty. They were the preeminent retrieving dogs on the British Isles. They fed the poacher and market hunter. During times of famine, the dogs were essential workers. Ducks and other waterfowl thrive in harsh conditions, and a dog that can pick them up is certainly useful. The same dog could also help poach pheasants and partridges around the wealthy estates. But when retrieving dogs were given their position in British and American shooting culture, these spaniels were forced to the side.

However, the need for a smaller dog lures people to the Boykins and Americans. The modern Irish breed has its unique charms and game-finding skills that attract some hunters, including those who just want something different.

And of course, today’s retrievers and spaniels still have water spaniel in them. The more retriever-like water spaniels were likely absorbed into retrievers, while the more spaniel-like dogs likely became part of the land spaniel strains. In this sense, water spaniels did not become extinct. They were simply absorbed into breeds that became part of the mainstream gun dog culture. They became part of the future, though changed in their essential features.

A remnant still holds on. It tells us of what once was, a message that pops up whenever a Labrador or Golden Retriever is born with a particularly curly coat. The blood is still there. Every once in a while, it emerges with these curly retrievers to remind you that it isn’t all gone. It is part of them, just as much as it is part of the history of retrieving dogs in North America and the British Isles.

Scottie Westfall is a native West Virginian who now lives in the backwoods of Central Florida. A long-time admirer of retrievers, he writes extensively about dog history at retrieverman.wordpress.com. He is passionate about studying the significance of dogs in human culture as well as their own evolution as a domestic animal.

Please take a look at the Australian Murray River Retriever to find the continuation of the lost original Water Spaniels…https://www.mrr.org.au/history They are breeding true in Australia since the 1800’s

Enjoyed the article. The Irish-Accented Narrator is a nice touch when hearing about dogs from Great Britain. Always wondered why how my English Springer Spaniels might have been developed to be water-dogs. Wish they had more Water-Spaniel influence bred into them😢.