Home » Grouse Species » Ruffed Grouse Hunting » Ruffed Grouse Drumming – The Mysterious Noise of Northern Forests

Ruffed Grouse Drumming – The Mysterious Noise of Northern Forests

A.J. DeRosa, founder of Project Upland, is a New England…

Learn everything we know about the unusual Ruffed Grouse drumming sound, from how they make it to trends in Ruffed Grouse populations.

The reverberation of a ruffed grouse drumming during early mornings in spring forests is one of the most magical sounds. When you hear it, it starkly contrasts against all other sounds found in the springtime. Its unique nature provokes human curiosity and admiration. No doubt, that very same feeling we get today is what sparked naturalist John Bartram to write a letter to his home in England in 1750, describing the unusual behavior of a bird he called the Ruffed Heath-Cock.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

“There is something very remarkable in what we call their thumping, which they do with their wings, by clapping them against their sides, as the hunters say,” wrote Bartram. “They stand upon an old fallen tree, that has lain many years on the ground, where they begin their strokes gradually, at about two seconds of time distant from one another, and repeat them quicker and quicker, until they make a noise like thunder at a distance; which continues, from the beginning, about a minute; then ceaseth for about five or six or eight minutes, before it begins again.”

While Bartram made an honest attempt to unravel the mystery of the grouse’s drumming, it would not be until the 20th century’s technological advancements that scientists finally cracked the code. Even today, we have learned so much about the behavior of drumming ruffed grouse thanks to dedicated scientists who have felt the same curiosity.

How Do Ruffed Grouse Make Drumming Sounds?

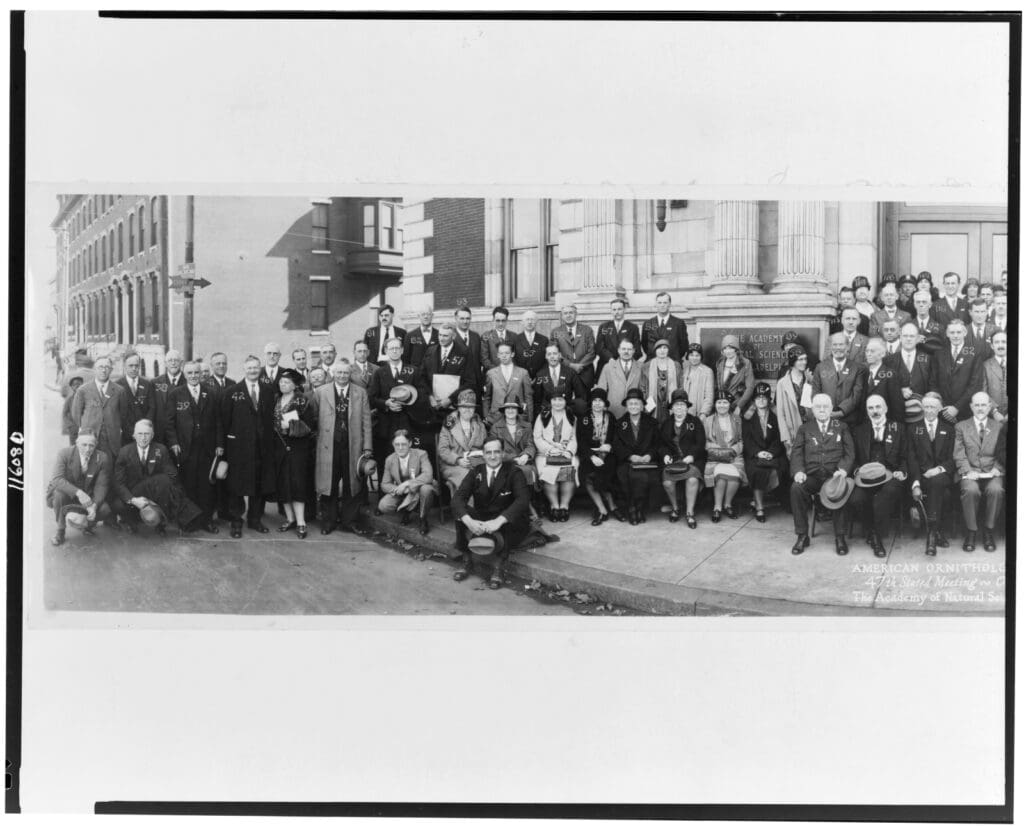

In 1929, 197 years after naturalist John Bartram’s observation, the schedule of the 47th meeting of the American Ornithologists’ Union listed a 15-minute presentation titled “The Courtship of the Ruffed Grouse” by Arthur A. Allen of Cornell University. Allen, an icon in ruffed grouse research, used a camera to film grouse drumming and finally discovered, as quoted by the iconic Ruffed Grouse researcher Gordon Gullion in 1984, “The drumming sound is made by the bird leaning back on his tail and striking his wings against the air violently enough to create a momentary vacuum, much as lightning does when it flashes through the sky.” Grouse quite literally create a small sonic boom. This discovery moved far beyond the old wives’ tales that suggested the drumming sound was produced by smacking wings together or by thumping on a hollow log.

In all my research, this discovery did not match the strangeness of his observations of a captive young male ruffed grouse who had never seen or heard another grouse drum. Allen’s description from 1934 states:

… after a few minutes of reconnoitering, he mounted the log and almost immediately assumed the drumming pose, first patting the log with his feet as though to test the stability of the spot which he had chosen. Then followed the quick stroke of the wings, another and another, and finally the roll and a blur of wings that made the dead leaves fly from in front of the log. There was no question that he knew instinctively what a drumming log was for, and knew how the drum should be produced; but he made scarcely a sound… Indeed it required nearly two weeks of constant practicing before the bird’s drum sounded like that of a wild bird… Since this bird had never seen nor heard another Grouse drum (having been hatched by a bantam and reared in a brooder), I think we are justified in concluding parenthetically that Grouse inherit an instinct to drum, just as I believe other birds inherit the instinct to sing.

Drumming comes at a significant cost to ruffed grouse. “The energy used to drum, plus the extended periods the birds spend on their logs in the peak of the spring season, causes them to sustain significant weight losses. Based on the recapture of males during the drumming season, it appears that active drummers lose about one-half percent of their weight daily during the three weeks of most intense activity” (Gullion 1984).

Why And When Do Ruffed Grouse Drum?

Gordon W. Gullion is perhaps the most renowned ruffed grouse researcher within the ruffed grouse community, and his work on the science of drumming is unmatched. Born in Oregon in 1923, his career spanned more than 60 years, and his legacy continues to influence us today. His contributions provide insights into the who, what, when, where, and why of ruffed grouse that have withstood the test of time.

No word count is large enough to sufficiently explore Gullion’s extensive research. His book, Grouse of the North Shore, is the result of decades of research in the Cloquet Forest in Minnesota. Its account of research includes the study of over 2,000 drumming sites that have been boiled down to some of the most important information in drumming research even 40 years after it was written. Grouse drum year-round, with the highest peak in spring during the breeding season followed by summer and fall, when territorial drumming occurs.

Gullion cites two reasons for the male ruffed grouse drumming or “displaying” behavior:

- Spring Breeding: According to Gullion, “It is most often heard as the snow melts in the spring and the breeding season approaches. Then anxious males are advertising their locations to hens looking for mates.” This timeframe peaks for a three-week period in the north country from the end of April into May in Minnesota. This timeframe seems to fluctuate based on location in the country, with some areas peaking in March and April.

- Territorial Defense: The second reason grouse drum is because of their territorial nature. “This is the act of one male announcing to all the others within hearing that the particular forest area he is occupying is all his.” This essentially occurs anytime we hear ruffed grouse drumming outside the breeding season.

Gullion found that drummers moved to logs in the middle of the night, most often in the early hours long before sunrise. And a fascinating pattern emerged. While the average time between drums was four minutes, ruffed grouse that were not engaged by either a mate or a challenger would decrease drumming in a pattern of four-minute intervals. “At other times, when a single bird is drumming and not being answered by others, the intervals between drums may be at multiples of four minutes, that is, at eight, 12, or 16-minute intervals.”

If you hear a drumming break decrease in length, it is an indication of a male bird being excited by the presence of another bird. At this point, drums can happen as often as one minute apart.

What Do Ruffed Grouse Drumming Sites Look Like?

There are micro and macro aspects to this question, leading to two significant components of drumming sites: what the grouse physically stands on to the drum and what the surrounding area (habitat) looks like. According to Gullion, drumming centers are normally eight to ten acres, or 148 to 159 yards apart. The most common place for a ruffed grouse to stand and drum is a fallen tree, hence the common term “drumming log.” Grouse also drum on rocks like glacial erratics or rock walls, with the rock wall scenario being unique to New England ruffed grouse. The “drumming stage” refers to a small, eight inch area that a ruffed grouse prefers on a drumming location to commence the behavior.

“The male grouse prefers to use a log or a site that places him nine to 15 inches above the ground on a log that is usually 20 to 40 feet long,” Gullion describes. “The bird choosing a drumming log has two primary considerations. One is to select a site that gives the maximum opportunity to advertise his presence; second, to select a site which gives him maximum security.” In any object selected for a “drumming stage,” it is the highest object in that immediate area.

Other key traits have come to light through decades of research. No large objects that could obstruct the view of an incoming predator are within a “50 to 60-foot radius.” Often an immediate “guard object” protects the drumming Ruffed Grouse, which includes a root mass, shrubs, or other objects. In the Cloquet Forest study, “guard objects” were present in 87.5% of drumming sites.

Stem density, the most commonly referred to aspect of ruffed grouse habitat, is the most prominent surrounding feature. Gullion found “the density of hardwood saplings is usually in the range of 3,000 to 7,000 stems per acre.” In Samantha Davis’ 2017 article titled “Survival, Harvest, and Drumming Ecology of Ruffed Grouse in Central Maine, USA,” there was a greater exploration into the significance of conifers in drumming sites, which are often more important in New England forests. They found, in contrast to older studies that believed coniferous areas were often deemed less preferable due to lower visibility and accessibility, that greater stem density is preferred in both deciduous and coniferous forests.

Gullion describes many types of “logs or centers” for drumming locations, which is a fascinating lesson on terminology. These are often dictated by the dominance found in a ruffed grouse population; usually the largest male birds are the most dominant. As populations change and fluctuate, there will be a natural shift based on dominance and resources to redistribute ruffed grouse drumming locations, and in years with overabundance, some younger male grouse will never even drum.

Perennial logs are those locations that are often selected because of their “ecological attributes” and will be occupied by many grouse over the course of years. Females will prefer to approach these locations because they present greater safety from predation. Transient logs are locations that were only used by one ruffed grouse and do not have another bird move in after it disappears. These places are usually of lesser habitat quality.

What Are Ruffed Grouse Drumming Surveys?

Many state agencies have been conducting drumming counts for decades. The overall goal is to identify population trends in ruffed grouse populations. The methodology itself, in its most basic form, is based on drumming routes where roadside counts are conducted. The surveyor stops at a series of predetermined locations that are consistent each year for a set amount of time so as not to create variables over the course of years. Each drumming event is recorded, and the data can show trends over time.

In B.C. Jones, C.A. Harper, D.A. Buehler, and G.S. Warburton’s article “Use of spring drumming counts to index ruffed grouse populations in the Southern Appalachians” from 2005, the importance of drumming counts as a viable measure to detect population trends was reconfirmed as an effective method as states look to put forth management plans in states that are showing alarming decreasing trends. This important study was conducted by Dr. Ben Jones, the now-President of the Ruffed Grouse Society and American Woodcock Society.

Technology might play a major role in the future of drumming counts for ruffed grouse, giving us more consistent data. In Lapp and his colleagues’ article, “Automated recognition of ruffed grouse drumming in field recordings” from 2023, the use of automated recognition overcame two major human hurdles: time and hearing. It significantly increased the detection rate compared to traditional field-based surveys. The equipment could also be deployed over a larger 28-day period to create more accurate and stable data sets.

Can Drumming Predict What Fall Populations Will Be?

Drumming activity can have implications about how hard the winter was. “When winter conditions have been more favorable, there may be half as many males on logs, but the drumming counts will be higher because birds are really excited about the approaching breeding season, and most, if not all, will be heard drumming each morning. This arouses the hens too, so there is a maximum reproductive effort resulting in many young grouse wandering around the woods in the fall” (Gullion 1984).

However, it is important to note that drumming counts cannot predict nesting success. In the most productive fall seasons we experience, the juvenile population can be larger than the adult population. Most recently, New Hampshire experienced an extremely wet spring that marked a high juvenile mortality rate, making the fall season dominated by adult birds and less than desirable compared to the year before. This only serves to highlight how much a single year of successful nesting and brood survival can impact a single year of ruffed grouse hunting.

Ruffed grouse utterly fascinate me. Every bird I encounter seems to be a paradox, appearing completely out of place yet simultaneously the perfect embodiment of its environment. In my life’s journey, grouse have evoked a range of emotions in me, including excitement, confusion, frustration, awe, and inquisitiveness, to name just a few. My expanding collection of out-of-print books, littered with highlighted text and sidebar notes, is a testament to my fondness. That haunting drumbeat in a thick northern forest represents more than our love for them; it represents a healthy, biodiverse forest.

A.J. DeRosa, founder of Project Upland, is a New England native with over 35 years of hunting experience across three continents. His passion for upland birds and side-by-side shotguns has taken him around the world, uncovering the stories of people and places connected to the uplands. First published in 2004, he wrote The Urban Deer Complex in 2014 and soon discovered a love for filmmaking, which led to the award-winning Project Upland film series. A.J.'s dedication to wildlife drives his advocacy for conservation policy and habitat funding at both federal and state levels. He serves as Vice Chair of the New Hampshire Fish & Game Commission, giving back to his community. You can often find A.J. and his Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, Grim, hunting in the mountains of New England—or wherever the birds lead them.