Home » Firearms and Shooting » The History of the John Dickson and Son Round Action Shotgun

The History of the John Dickson and Son Round Action Shotgun

- This article originally published in the Spring 2021 (3.1) issue of Project Upland Magazine.

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's…

Dive into the history of the Scottish gunmaker John Dickson and his round-action shotgun, what some consider the finest side-by-side in the world

Imagine you’re rich. Not comfortable, as in, “The house is almost paid for,” and not well off, as in, “The kids go to private school, and I drive a Platinum Ford F150.” Imagine you’re stupid rich, as in, “I’ve got a new Gulfstream jet plus a couple hunting ranches out West.”

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

If you had that kind of money, which shotgun would you buy? A 16-gauge Parker DHE? A Perazzi over-under? Maybe a vintage Purdey? Or would you go big and order a pair of custom round-action side-by-sides from John Dickson & Son?

In 1910, a Scottish man named John Campbell Connell faced a similar dilemma. He was in the market for a pair of shotguns, and because he was from a family of wealthy shipbuilders, London’s most prestigious and expensive gunmakers would have been within his reach: James Woodward and Sons, Boss and Co., Holland and Holland, James Purdey and Sons. So why did he buy round-action shotguns from John Dickson and Son of Edinburgh?

He wasn’t being frugal, that’s for sure. Dickson’s round actions were expensive, costing as much as any other best quality British shotgun. Was Connell unaware of the famous side-by-sides being built in London? Doubtful. With his family’s connections, he would have run in circles where he would have seen Purdeys, Hollands, Grants, and other top-shelf doubles. Were the Dicksons a tribute to his Scottish ancestry? Perhaps. Or had Connell had already concluded what many people believe today—that the Dickson round action is the finest shotgun in the world?

The history of firearm production in the UK and the rise of Dickson round action shotguns

Every side-by-side has barrels, stocks, and locks. But on guns like an A.H. Fox or a Westley Richards, the locks (the hammers, mainsprings, trigger sears, and parts that make the gun go bang) are housed inside the action. On an L.C. Smith or a Purdey, these components are mounted on plates fixed to either side of the action. Guns set up the first way are boxlocks; those set up the second way are sidelocks.

Almost every side-by-side made since 1850 falls into one of these two categories. Almost.

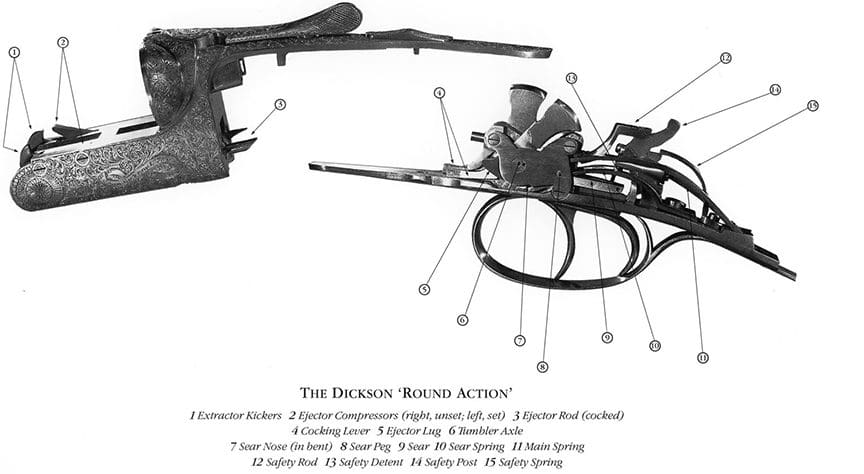

The first time I saw a Dickson round action, I didn’t know what to make of it. I was at a gun show in Rhode Island, and the Dickson was lined up on a table along with Parkers, W. and C. Scotts, Lefevers, and other side-by-sides. Compared to those guns, the round action was sleeker and far more elegant. And while all the doubles on that table looked snaky with their long barrels, the Dickson looked like it would slither away if I tried to touch it. The action was as narrow as an old-school hammergun—too narrow to house the hammers, mainsprings, and sears. So how did the gun fire? I could see the triggers, but I had to pick up the gun and flip it over to see where the locks were hidden. What I saw—a broad trigger plate, two fingers wide, fitted into the stock above the triggers—revealed the round action’s secret and the genius of its design.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Great Britain was crazy about shooting. As people chased after everything from red grouse to a good time, shotguns, rifles, and pistols blazed from estates in northern Scotland to the gentlemen’s clubs in London. In May, June, and July, the nation’s richest sportsmen and hundreds of spectators attended live-pigeon trap shoots at prestigious venues like the Gun Club. Newspapers like Bell’s Life in London, and Sporting Chronicle covered these shoots like NFL games and published the weekly results in between reports on other popular Victorian activities like cockfights and bare-knuckle boxing. Starting in August and running into the winter, trains chugged out of London carrying aristocrats and other wealthy people off to lodges and shooting parties throughout the United Kingdom. Regular people with the money for guns walked to local shooting grounds and farms where they hunted pheasant, partridge, and hare.

While all this shooting was happening, the British government encouraged people to join groups like the West Yorkshire Rifle Volunteers and the London Rifle Brigade to learn marksmanship. Members furnished their rifles, and the groups practiced marksmanship and competed against one another at ranges throughout the country. Starting in the 1860s, the biggest event of the year was the Wimbledon Rifle Match. It ran for a week and Saturday was the biggest draw. Throughout the day, shooters aimed their black-powder rifles at plate-sized targets at 800, 900, and 1,000 yards away. Thousands of spectators did their best to follow the results through the clouds of white smoke that boomed out from the rifles and rolled out over the shooting fields.

As you can imagine, all of this shooting created a huge demand for firearms, ammunition, loading equipment, and other supplies. This meant there were fistfuls of money to be made in the firearms trade. In 1838, a Scottish gunmaker named John Dickson set out to grab some of it for himself.

Is 12 years old too young to start a career? John Dickson’s parents didn’t think so. In 1806, they made him an apprentice to James Wallace, the finest gunmaker in Edinburgh. Dickson’s apprenticeship was completed seven years later, and at just 19 he became Wallace’s foreman. In 1820, he struck out on his own as a gun trade contractor or someone who builds gun parts for other makers. Then, in 1838, Dickson opened his shop and started building guns under the name John Dickson and Son.

The new business was on Princes Street, one of the swankiest parts of Edinburgh. Its neighbors were some of the most prestigious and expensive retailers in Scotland. John Dickson and Son fit right in. Within a few years, wealthy shooters were placing orders for Dickson’s shotguns and rifles. But Dickson wasn’t the only gunmaker in Edinburgh, and there were many other first-rate gunmakers in the U.K. To keep orders coming in, Dickson had to stay on top of innovations like breech-loading, centerfire guns. To prosper, Dickson needed to come up with innovations of its own, and, in 1880, John Dickson and Son launched just such an innovation.

The rise, fall and revival of the Dickson round action shotgun

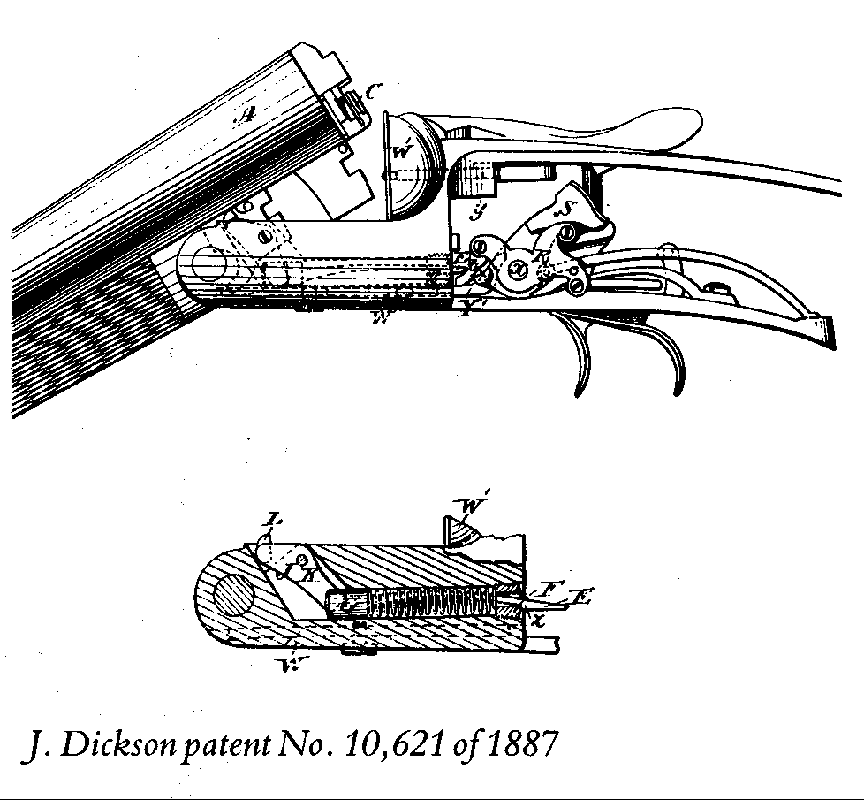

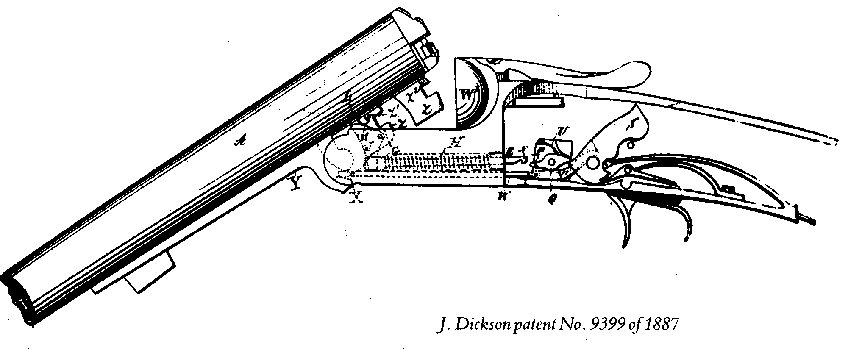

Many people think Dickson round actions are as Scottish as clan tartans and kilts. But that’s not 100 percent true—the idea for these guns came from Germany. In 1879, an Edinburgh gunmaker named James MacNaughton, who had apprenticed with John Dickson and Son in the 1850s, built a gun based on an unusual design he had learned about from a German-born gunsmith named Julius Coster. This design placed the hammers, mainsprings, and sears on the same plate that held the triggers (the triggerplate). MacNaughton called his shotgun the Edinburgh. In 1880, John Dickson and Son created its version of MacNaughton’s triggerplate gun and called it the round action. Dickson had been building hammerless, centerfire shotguns (Anson and Deeley-patented boxlocks and Scott and Baker-patented sidelocks), but while these guns were top quality, they used other makers’ signature designs (Westley Richards and W & C. Scott). With the round action, John Dickson and Son had a design it could call its own and a way to join the big leagues of British gunmaking.

In his book about John Dickson and Son, Donald Dallas sums up what attracts so many people to the company’s famous side-by-side: “The round action is one of the most graceful guns ever built.”

This gracefulness is possible because the lockwork on a Dickson round action sits on the triggerplate. There’s no need to leave room for it in the action, and there’s no need to leave room for sideplates. This gave Dickson the freedom to scale down the action and sculpt it into an elegant shape while keeping it exceptionally strong. It also allowed the maker to create special lightweight models as well as several three-barrel, three-trigger guns that handled like regular side-by-sides.

With its great looks and unique features, the round action was a hit right away. Within a few years, it made up almost half of Dickson’s annual production. Dickson added cocking indicators in 1882, ejectors in 1886, and, in the decades that followed, refined the mechanics and tweaked the gun’s appearance. Dickson also made round actions with sidelevers, 15 round action double rifles, and 19 with what they called a skeleton stock. In 1888, John Dickson and Son applied its round action design to a unique over-under. Always willing to please a customer and close a sale, Dickson even built round actions to look like boxlocks and sidelocks.

John Dickson and Son thrived into the 20th century for two reasons: the appeal and quality of its round action (the company’s most successful and expensive model) and by continuing to build a diversity of other guns including boxlocks and sidelocks (plus some hammerguns), bolt rifles, and pistols. By the time John Campbell Connell ordered his pair of round actions in 1910, the company had gone from a respected local gunmaker to one of the top names in the U.K. Dickson held five gunmaking patents, and, since 1880, they had sold more than 750 round actions. So while Connell was purchasing a unique design, it was from a time-tested, top-tier maker.

As the round action rose to prominence, so did the family behind the business. In 1880, founder John Dickson Sr. died, aged 86. He had come from a poor background to create one of Edinburgh’s most successful gunmakers. His grandson, also named John Dickson, oversaw the introduction of the round action and ran the business through its most prosperous times.

In 1923, he sold the company to a local businessman and retired to a stately home in Edinburgh. John Dickson and Son retained its name and kept building its famous round action guns under its new owner. Business was good during the 1920s but suffered during the Great Depression and into World War II. After the Nazis were crushed, it took years for Great Britain and the rest of Europe to recover from the devastation of the war. Orders at John Dickson and Son never returned to pre-war levels, and, in the 1950s, Dickson made just 23 round-action guns. Business improved in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, but by then Dickson had decided to concentrate on boxlocks and sidelocks. Very few new round actions were built. The 90s were better for the company’s signature gun, but not great. After the turn of the 21st century, John Dickson and Son refocused on its round action, and, in 2019, the company was bought by gunmaker J.P. Daeschler who remains committed to building, repairing, and promoting the John Dickson and Son round action.

The appeal of the Dickson round action shotgun

Personal preferences are tough to quantify. One person likes Pointers, another Setters. When they try to explain their tastes, they often reply with, “There’s just something I like about them.”

Fair enough. That response is absolutely fine—and absolutely human. We’re complex creatures, and, even though we like to think our minds are in charge, our hearts call the shots most of the time. Understanding why one thing appeals to our heart over another is impossible to do. But I’ll give it a shot.

I’ve always been impressed by Dickson’s round actions; first by their gracefulness and elegance, then by the uniqueness of their design, the strength of their actions, and the handy way their ejectors function. On top of these obvious, rational reasons to admire them, round actions also have a powerful “it” factor—an undefinable charisma—working for them. Maybe it’s because they’re Scottish, like so many of us, or maybe it’s due to their exoticness. John Dickson and Son has built fewer than 2,000 round actions, and only one other maker—fellow Scot David McKay Brown—has built similar guns. James Purdey and Sons has produced over 25,000 of its signature model, and there are hundreds of thousands of sidelocks out there similar to Holland and Holland’s. Perhaps it’s because the round action’s roundness feels more organic than other shotgun designs, an idea suggested by a gunsmith named Steve Davis who is the top authority on round actions in the United States.

Whatever this “it” is, Dickson round actions have plenty. People are passionate about them, loving them as much as bird hunters prefer one breed of dog over another. For many, a big part of the round action’s appeal is the way these guns handle. Compared to boxlock and sidelock shotguns, Dickson round actions concentrate more weight right behind the action and above the triggers. Some people find that this gives round actions a livelier, more dynamic feel that makes them easier to shoot.

“I don’t know why, but I kill more pheasants with my Dickson, especially on crossing shots,” said one person I spoke with about these guns.

Another noted an instinctive feel to how his Dicksons shoot: “I just keep my eyes on the bird. The gun comes up and the birds go down.”

Over a century ago, John Campbell Connell may have shot a Dickson and experienced the same effortless handling for himself. Whatever convinced him to order his pair of round actions, it must have made a huge impression on this man-who-could-have-anything. If you find yourself in the same position one day, you should order a John Dickson and Son round action right away.

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's been interested in shotguns and gundogs since he was a kid. Today, he blogs about both at www.DogsandDoubles.com and posts to Instagram @dogsanddoubles

this is one of the finest brief articles about Dickson shotguns I have ever read. As someone who has been looking for years for one in decent condition, I am grateful for this information.

Thanks. I’m glad you liked it. Have you had any luck finding a Dickson?

Gregg