Home » Hunting Dogs » Meet Fin, an Invasive Mussel Detection Dog

Meet Fin, an Invasive Mussel Detection Dog

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was…

How one conservation dog helps the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife combat the spread of invasive aquatic mussels

This article was originally published in volume five of Hunting Dog Confidential. This story was illustrated by Naomi Coates.

While growing up in southern Wisconsin, I spent many beautiful summer days at Lake Ripley. Turtles sunned on little logs, and minnows nibbled your toes if you stood real still. Kids and parents enjoyed the warm water without any fear of sharp mussels cutting their feet. Back then, there wasn’t a need for a mussel detection dog to inspect boats for invasive species.

But then, in 2007, state biologists and Lake Ripley Management District volunteers discovered invasive zebra mussels in the lake. After the first time a zebra mussel sliced open my toes with its sharp exterior, I became nervous about touching the lake bottom with bare feet. Water shoes became essential. Before long, everyone knew that the bottom of the lake was to be avoided. In 2021, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources declared the lake “infested” with these stripey invertebrates.

State wildlife agencies aren’t just monitoring for zebra mussels. Quagga mussels are also harmful to native ecosystems and spreading across the United States. Quagga mussels are native to Ukraine, and zebra mussels belong to the drainages of the Caspian, Black, and Aral Seas. Within their native ranges, these species act like any other mussel species. However, outside that range, they are more than just an annoyance to beachgoers—they’re an ecological scourge. As a result, some state wildlife agencies are adding mussel detection dogs to their invasive species units.

Invasive Mussels And Their Impacts on Watersheds

As of September 2023, invasive quagga and zebra mussels exist in 30 states and two Canadian provinces. These two species wreak havoc on aquatic ecosystems in many ways. New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services states that just one female zebra or quagga mussel can produce 1,000,000 eggs annually. While it’s common for only one percent of their eggs to survive, that means 10,000 of their microscopic larvae grow into juvenile mussels. These species become sexually mature at one year of age, so one pair of male and female mussels can quickly turn into thousands.

They’re also highly efficient at filtering water. As a result, they remove large quantities of phytoplankton from lakes, decreasing the food availability for other species, including native mussels. While one benefit to this is clearer water, the increased clarity correlates with higher frequencies of algal blooms, according to the University of California Riverside. Smelly, rotten blooms and dead mussels build up along lakeshores, deeming popular recreational beaches unusable.

These mussels bioaccumulate pollutants because they absorb the gunk they filter out from waterways. As a result, mussels decrease the contaminants in lakes but increase the risk of avian botulism outbreaks. In the Great Lakes region, this has led to the “mortality of tens of thousands of birds,” according to UC Riverside.

Additionally, these animals prefer to cling to hard surfaces like water intake structures, water treatment plants, power plants, docks, buoys, anchors, boat hulls, turtles, crayfish, and the shells of native mussels. They effectively clog pipes, engines, and other types of expensive equipment, rendering them inefficient at best and totally useless at worst.

“It has been estimated that it costs over $500 million per year to manage mussels at power plants, water systems, and industrial complexes, and on boats and docks in the Great Lakes,” states UC Riverside. Invasive mussels are practically impossible to remove once they’re established. The only way mussels can be removed from these surfaces is by manually scraping them off or administering toxicants, which are very costly and time-consuming.

The Columbia River Basin, located in the northwestern United States, is the only uninfected watershed remaining in the country. In 2020, the Bureau of Reclamation estimated that “a full-blown infestation would cost its citizens $500 million annually in lost economic production, higher electric rates, and risk more endangered species complications.”

Protecting the Basin by avoiding a mussel infestation is paramount to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). Thankfully, it has a mussel detection dog, Fin, on its side. His well-trained nose detects mussels before they can get into the state’s waterways.

Selecting A Mussel Detection Dog

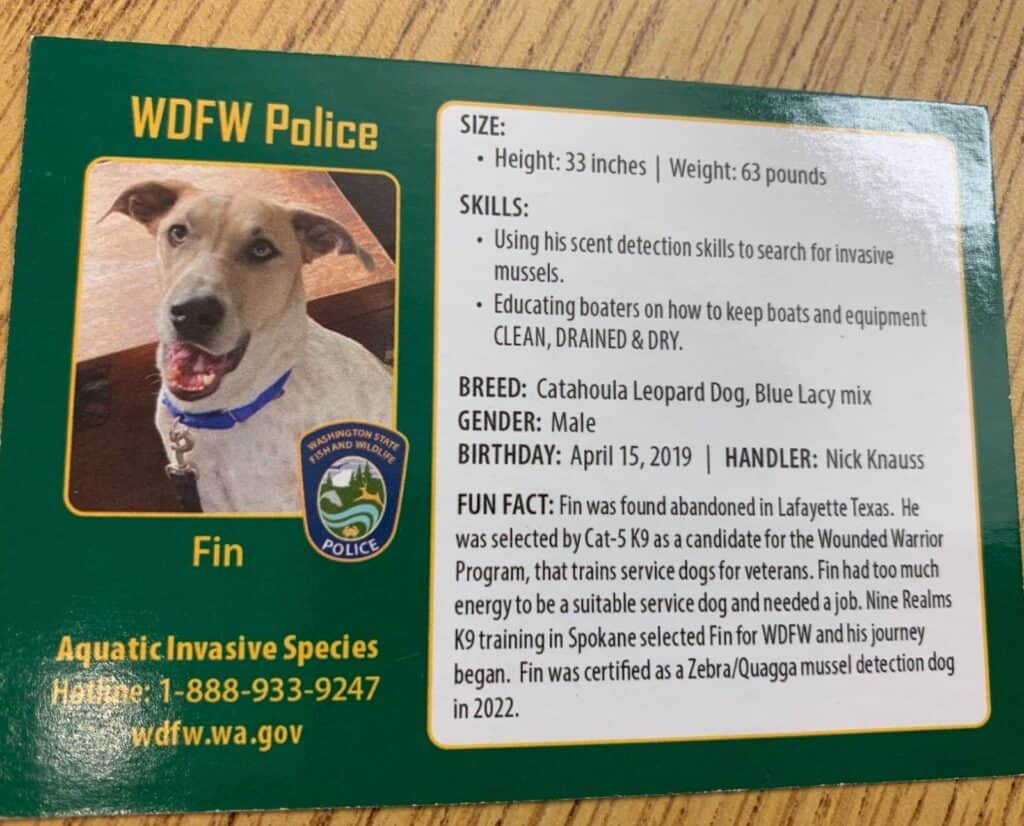

Fin is a three-and-a-half-year-old Catahoula Leopard Dog, Blue Lacy, and Australian Cattle Dog mix from Lafayette, Texas. After being abandoned by his previous owner, Cat-5 K9 selected him as a potential service dog with the Wounded Warrior Project. Unfortunately, Fin didn’t quite fit the bill to become a service dog; his endless energy was too much for retired veterans. However, the folks in Texas knew he needed a job to reach his full potential.

Around the same time, WDFW called out to dog trainers and rescues, stating that it was searching for a mussel detection dog. The agency needed a friendly, approachable dog who would be good with other pups, kids, and large crowds. The ideal dog would also have lots of energy.

WDFW contacted Spokane’s Nine Realms Canine Training to get some help matching up with the perfect pup. Karin Wagemann, the owner and head trainer at Nine Realms, found out about him shortly after. She realized he checked every box WDFW was looking for and knew he would be a good fit.

“Because mussel detection involves a lot of the same old routine, dogs get bored unless they have an extreme drive for the hunt,” said Wagemann. “We look for dogs with a high toy drive, who want to play fetch or tug all day long, and will search tirelessly for their ball or toy in any environment without getting distracted.”

Training Mussel Detection Dogs

Wagemann specializes in training law enforcement, anti-poaching, and service dogs. When training detection dogs in particular, she usually teaches them how to detect narcotics, explosives, and human remains. Unsurprisingly, training dogs to find invasive aquatic mussels on a boat is just a small part of her job.

“Because the dog only has to detect mussels on watercraft, the training is shorter than for a bomb or narcotics dog, which has many more layers of areas to learn to search and odors to look for,” said Wagemann. The average time it takes to train a mussel detection dog is about four weeks. Her training is based on the fact that selected dogs naturally want to hunt for their ball.

During the first week, Wagemann pairs the ball with the odor of mussels. “The dog learns that when he hunts for his ball, there is always the odor of mussels with it,” she said. At first, Wagemann uses boxes to hide the scent-laden ball. However, she quickly moves on to using watercraft. “Within the second week of training, I go straight to teaching the pattern around the boat,” she said.

In addition to encouraging the dog to hunt for a mussel-scented ball, she teaches it to sit or lie down once the ball is detected. This tells the handler that the ball (or mussels) has been found. Then, after about two weeks, Wagemann begins removing the ball from the mussel odor. “I never return the ball to the odor once the dog finds and sits on the odor,” she continued. The goal is to have the mussel detection dog actively search for the invasive species, then be rewarded immediately after the hunt is over whether it detects mussels or not.

“It’s becoming more and more important to have conservation dogs,” Wagemann said. As state wildlife agencies continue to add canines to their teams, she urges them to be sure they’re employing dogs with high enough toy and hunt drives to do their job to the utmost of their ability. Having a dog that only partially works or doesn’t work at all is no help to conservation efforts.

Meet Fin’s Handler, WDFW’s Nick Knauss

After spending several weeks with Karin, Fin successfully became a certified mussel detection dog. He started working with WDFW in 2022. Fin’s the second dog to be part of Washington’s invasive species control program. Technically, he belongs to the state, but after work, he goes home with his handler, Nick Knauss.

“He lives with me. He’s a part of my family,” said Knauss, an aquatic invasive species inspector and K9 handler for WDFW. “The sergeant saw potential in me as a dog handler, and I expressed a lot of interest in the position. When she and Puddles, her mussel dog, both retired, she introduced me to Karin. Karin said, ‘Yup, he’ll do!’”

Knauss’s background is in marine science. However, he got a little tired of waves constantly smashing his body against cliffs. Before long, he found himself working in the state’s invasive species unit. After five years of checking boats for invasive mussels on his own, his sergeant retired, opening up the opportunity for him to become a mussel dog handler and gain a highly efficient coworker.

“Nick worked at one of our boat check stations,” said Staci Lehman, the Communications Manager for WDFW. “He used to check boats by himself, but Fin speeds everything up.”

“When you’re checking a 40-foot boat for a little tiny mussel, Fin makes the process much quicker,” said Knauss. A big zebra or quagga mussel is only about the size of a quarter; it’s far easier for a dog to sniff out the small mollusk than it is for the human eye to notice them on a rudder or hull.

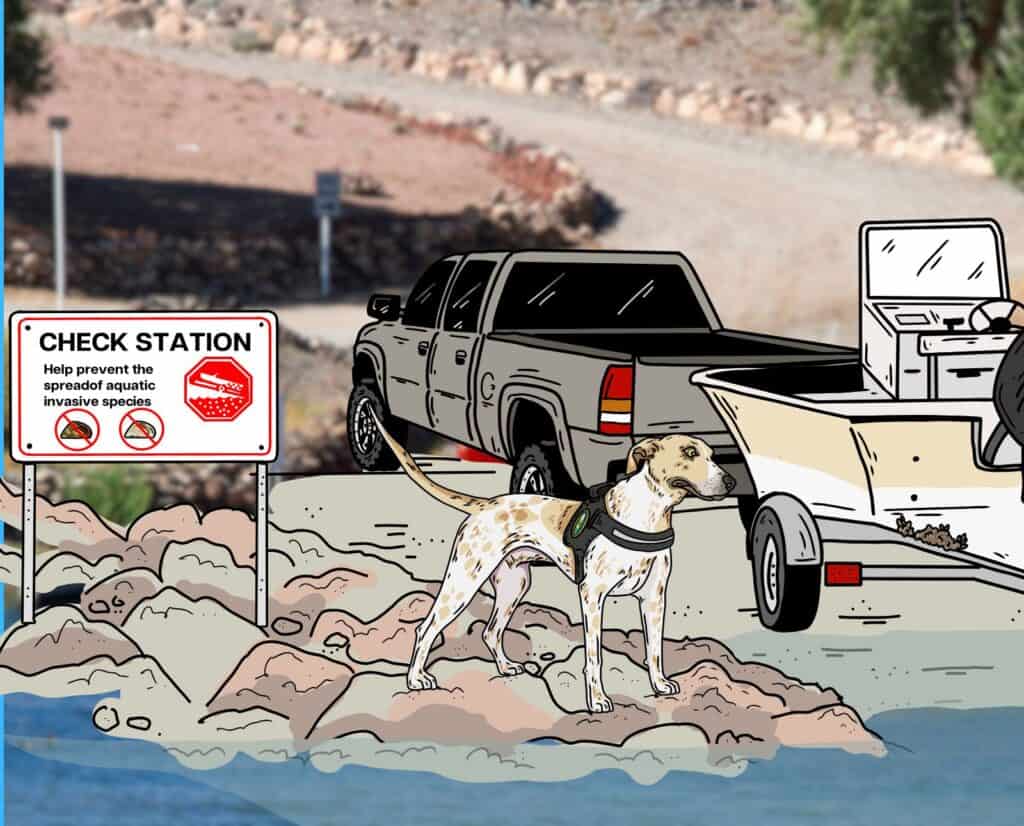

How Mussel Detection Dogs Help at Boat Check Stations

When Fin’s working as Washington’s only mussel dog, part of his job is hanging out at mandatory boat check stations. Fin can check anywhere from five to 300 boats in a single day. 2023 was his first full year working for the agency. That year, Fin completed 802 boat inspections, attended 23 events, and helped teach 4,935 people about mussels.

Most boaters entering the state have never seen a mussel-sniffing dog before. To help these folks understand what Fin is there to do, one of Knauss’s coworkers briefs each driver before Fin begins his search. Meanwhile, Knauss and Fin approach the trailered boat.

“Fin’s command to search for mussels is ‘Find It.’ I let him go, and he searches around the boat,” said Knauss. “His entire job typically takes 30 seconds. During this time, he trots around the boat; to an outsider, it really doesn’t look like he’s doing anything. If he detects something, his head will snap around, and he’ll sit and not move. He’s not trained to bark, but he is very excited, so he barks, too.”

As long as Fin successfully searches for mussels, he’s given his favorite toy. Fin and his handler then play around for a while as a reward. As long as he doesn’t give Knauss a false positive, Fin gets rewarded. If Fin finds mussels, those invertebrates are manually removed from the watercraft while Fin is being praised. By the time the next boat pulls up to the check station, he’s ready to return to work.

Invasive Mussels And Boats In Washington State

The sanitation ramp at the boat check station is self-reclaimed, so none of the water used to remove the invasive mussels gets into Washington’s river systems. “We use 140-degree water to kill them, and then high-pressure water to knock them off,” said Knauss. The ramp collects all the spent water and hosed-off mussels.

“Right now, this service is provided free of charge,” Knauss continued. “We want people to want to come to Washington, not feel deterred from boating in this state. Our goal is for folks to come in, see us, and get their boats checked.”

“At our boat check stations, we hear everything from ‘You’re violating my rights’ to ‘You can’t get in my boat,’” said Lehman. “This is only an exterior search. It is super quick; you’re in and out. We’re only concerned about the spread of invasive species.”

Washington has laws detailing that citizens will be fined if caught bringing an invasive species into the state. If boaters don’t pull into mandatory check stations, comply with a decontamination order, or fail to follow other requirements set by Revised Code of Washington 77.15.809, they violate the law. If caught, they could receive the maximum penalty of one year in jail and $5,000 in fines.

“Ideally, everyone comes into the boat check station and lets us quickly handle any contamination problems Fin detects. Then, they’re off to have a fantastic day on our waters,” said Knauss.

Fin Is A Conservation Ambassador

The other half of Fin’s job is educating Washington residents and visitors about quagga and zebra mussels and why the state is so driven to protect its watersheds. Fin travels around to schools, boat shows, and libraries to help teach kids, boating enthusiasts, and the broader Washington community how he helps conserve and protect native species.

“Fin is a great ambassador and a fabulous way to educate people about invasive species,” said Lehman. “People approach Fin to pet him, and Nick tells them what Fin does for work. They’re surprised and impressed. They have no idea a mussel detection dog is a real thing. One day with Fin out in public or at the boat check station has an incredible reach.”

“Most kids don’t care about mussels,” said Knauss, “but when we bring Fin around, they get super excited about them.” WDFW is actively engaging the state’s youth. It even hosted a high school art contest in 2022. Students in grades nine through 12 were encouraged to design the trailer wrap for the agency’s Invasive Species Education Trailer.

The winning wrap is expertly designed. It features information about invasive land- and water-dwelling invasive species and portraits of Fin and Puddles, his retired predecessor, on the back.

“When I retire, Fin will come with me, too,” said Knauss. “To the state, a working dog’s ‘lifespan’ is five years. So as long as I’m with him for five years, his tenure will be up, and after that, he can be a normal dog.”

What happened at Lake Ripley in Wisconsin is exactly what the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is trying to prevent. With Fin on duty, the agency is not only speeding up inspections, but also building public awareness and inspiring the next generation of dog lovers and outdoor enthusiasts. Thanks to this high-energy conservation dog, Washington is staying one step ahead in the fight to protect its last uninfested watershed.

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was born in Maryland and raised in southern Wisconsin, where she also studied wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2018, she moved to Gunnison, Colorado to earn her master's in public land management from Western Colorado University. Gabby still lives there today and shares 11 acres with eight dogs, five horses, and three cats. She herds cows for a local rancher on the side.