Home » Conservation » The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon

The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to…

Learning about bird species extinction from the passenger pigeon

Unless you’re pretty conservation-minded, you may not have even heard of the passenger pigeon before. But as a biologist, it’s one of the first cautionary tales I learned about in school. Here’s a glimpse into what this fascinating bird was like, and why it’s important that we look back to learn from its story.

What was the passenger pigeon?

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a large member of the pigeon family in eastern North America that went extinct over 100 years ago. These birds measured about 16 inches long with a 2-foot wingspan and weighed between 0.5 and 0.75 pounds (PA Game Commission 2010). They fed on hard mast (e.g., acorns, beechnuts, chestnuts, etc.), soft mast (e.g., wild grapes, berries, etc.), and insects or worms. But the most remarkable thing about this pigeon is that its population is estimated to have once been in the billions, accounting for more than a quarter of all land birds in North America (USFWS 2014)! There are multiple accounts of how a single flock (hundreds of millions of birds) sounded like a train passing by and would block out the sun for several hours, and how trees would snap under the weight of all the birds and nests.

Tragically, the entire population (billions of animals) was wiped out by the early 20th century. In fact, the last known bird (a female named Martha) died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914 at the amazing age of 29 years. While it wasn’t the first North American wildlife species to go extinct due to human influence, it was staggering how fast such an abundant species could be eliminated. How was it possible?

What caused the passenger pigeon’s extinction?

There are a few reasons the passenger pigeon was brought to the point of extinction. Market hunting and over-exploitation were the primary culprits.

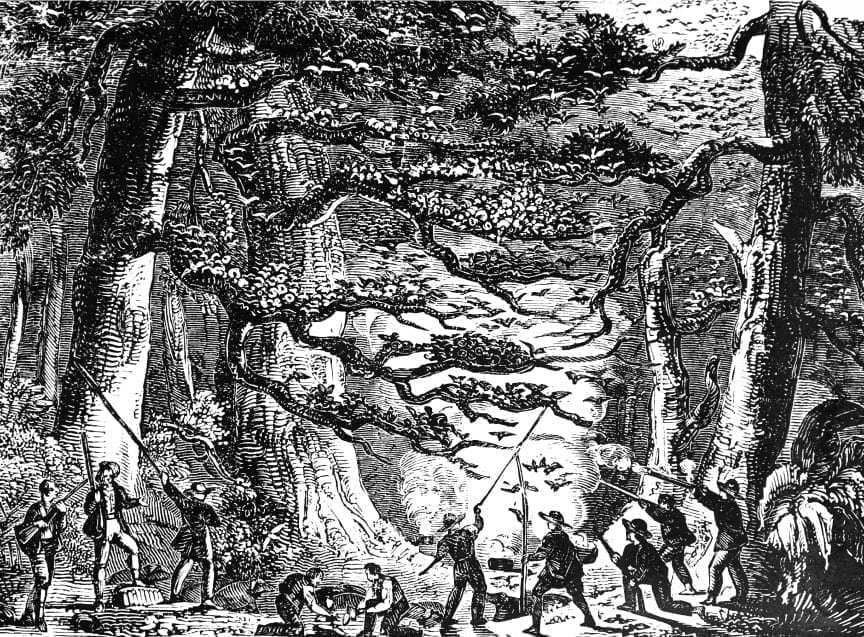

Because their flocks were so gigantic, firearms, nets, clubs, and poles were used to quickly harvest thousands of pigeons at a time. The invention of the telegraph and railroad transportation across the country allowed humans to quickly locate roosting areas for harvesting squab (i.e., young pigeons), and trees were often cut down to gather them easily. Railcars literally full of pigeons would leave for larger markets daily (PA Game Commission 2010). Forests full of food sources were replaced by agriculture and other developments. After decades of diminished reproductive success (called recruitment), loss of habitat, and direct mortality, the population reached a tipping point from which it couldn’t recover.

Based on the tremendous population size, you’d think passenger pigeons were extremely prolific breeders. But in reality, females usually laid a single egg annually and they simply couldn’t keep up with what was being removed. Murray et al. (2017) indicated that passenger pigeons likely went extinct so fast because a rapid reduction in genetic diversity made it impossible for them to adapt to human pressure in time. The species had adapted to survival in staggering flocks because there’s usually safety in numbers. But when those populations crashed due to over-exploitation, their survival mechanisms just didn’t work any longer. It actually made them more vulnerable, and we kept pushing until it was too late.

Environmental laws introduced

Towards the end of the 1800s, legislators started receiving petitions to protect the birds, efforts which were unfortunately largely ignored. After all, how could humans possibly impact a seemingly endless resource? But that’s exactly what happened. By the time it was actually noticeable, it was already too late.

Finally recognizing these devastating trends, Congress passed the first federal wildlife protection law, the Lacey Act of 1900. Similar conservation and preservation laws and additional hunting regulations came into effect around the same time. Shortly thereafter, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 was passed, which protected migratory birds and their eggs, nests, or feathers. In the late 60s, there were a few iterations of endangered species laws, which eventually culminated in passing the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Nearly 50 years later, the ESA is still a critical environmental law that protects and allows us to restore species on the brink of extinction.

Relevance for current trends

So how does this apply to wildlife species or our society today? Our influence on the environment is increasing each year, and many wildlife species are struggling to adapt quickly enough. There’s a real need to understand our effects on whole populations, habitats, and ecosystems.

- For instance, recent research (Smith et al., 2020) seems to indicate that focusing on micro features to enhance sage grouse habitat may be actually hampering our efforts to save the species. Instead, the researchers suggested we should be looking at habitat effects on the larger landscape, such as conifers replacing sagebrush habitats or conversion to agriculture. Those will likely have a more dramatic effect over time.

- Or look at the decline of the ruffed grouse. A drastic reduction in young forest habitat across their range, in combination with other threats (e.g., West Nile virus, predators, weird weather events, etc.), is a lot to throw at a species in a relatively short time span. Many states are struggling to support grouse where they once were abundant, and that’s a worrisome sign.

- And then there are sharp-tailed grouse. Many agencies and scientists agree that the effects of climate change will add to the existing habitat loss and fragmentation we have already caused. For that matter, there are actually a lot of similarities between the passenger pigeon and climate change. Many people still maintain that we couldn’t possibly impact the global atmosphere, which is exactly why it’s so dangerous. Like the pigeon, we may not open our eyes until we’re past the tipping point and it’s too late.

While we no longer allow market hunting and we have plenty of laws protecting wildlife, it turns out there’s a lot we can still learn from the story of the passenger pigeon. John F. Lacey (author of the Lacey Act) once stated, “We have given an awful exhibition of slaughter and destruction, which may serve as a warning to all mankind. Let us now give an example of wise conservation of what remains of the gifts of nature.” We can’t ignore the trends we’re seeing today. We owe at least that much to the passenger pigeon, heath hen, and many other species we’ve already written off to the pages of history.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION for FREE : Google | Apple | Spotify

ProjectUpland.com On the Go is brought to us by: ESP – Digital Hearing Protection

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to several outdoor manufacturers, hunting shows, publications, and blogs. He is an avid small game, turkey, and whitetail hunter from northern Minnesota and loves managing habitat almost as much as hunting. Ryan is also passionate about helping other adults experience the outdoors for their first time, which spurred him to launch Zero to Hunt, a website devoted to mentoring new hunters.

“Unless you’re pretty conservation-minded, you may not have even heard of the passenger pigeon before.” I think you’d be hard pressed find anyone with half an education that hasn’t heard of the passenger pigeon biologist or not.

As far as the birds blocking out the sun, I have heard that over and over as I heard that salmon runs in the 19th century were so large that you could walk across the river on the backs of fish. Having witnessed several record red salmon runs in Alaska, yes the fish are think but I would try walking across the river on the backs of the fish. 19th century people were prone to exaggeration, fishermen and hunters being among the worse in this regard. It makes me believe that both stories are apocryphal.

Of course after coming back from Argentina I would tell everyone that the doves were so thick that they blocked out the sun. Embellishment tends to be a trait of hunters and fishermen no matter the century.

And how far back are the bobwhite quail from being extinct

There’s more than enough genetic material in the mounted Passenger (The true and original name is Passager Pigeon, as in the ” Grand Passage migration) Pigeons on display in museums to clone a new effort for reintroduction. I read once there’s a group working in just such a project. We made them extinct. It’s

our duty to bring them back. They belong in Appalachia.