Home » Conservation » The Extinct California Wild Turkey: Meleagris Californica

The Extinct California Wild Turkey: Meleagris Californica

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada…

Drought-like conditions combined with heavy predation led the California turkey to extinction over 10,000 years ago.

Depending on where in the world you’re hunting turkeys, you may be fortunate to see other remarkable wildlife while you sit and hammer on your box or slate call. You may even have one or two curious predatory critters come into your calls, hoping for an easy meal.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

For many modern turkey species, their main predators are owls, coyotes, and cougars. But what if they were golden eagles, sabertooth tigers, or dire wolves? What about sitting on the edge of a clearing and watching giant ground sloths, mammoths, and mastodons frolic in the early morning mist while you wait for a big old tom to come in?

For the extinct California turkey, life, including the flora and fauna that surrounded them, looked very different from today.

Discovery and Classification of the California Turkey

The California Turkey, or Melegaris californica, was first identified by samples found in the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California, by Loye. H. Miller in 1909. Unfortunately, his initial assessment incorrectly classified this biological evidence as being part of the peacock family. However, he later changed his understanding and theory, believing it to be an intermediary species between peacocks and turkeys. It wouldn’t be until 1924 that his findings were correctly classified as its own unique but extinct species, one that had been isolated from cross-breeding with other subspecies of wild turkey due to its geographic location and the physical barriers found in the desert and surrounding mountains.

La Brea Tar Pits and Museum researchers highlight how natural barriers protected the California turkey gene pool while also isolating it, prohibiting cross-breeding with other subspecies, “We have not been able to successfully retrieve DNA from fossils at the La Brea Tar Pits. That being said, it appears unlikely that the California turkey interbred with the modern wild turkey, as their distributional ranges seem to have been divided by the Sierra Nevada during the late Pleistocene. It is thus improbable that any genetic material in modern turkeys comes directly from the extinct California turkey.”

Based on its fossil records, the California turkey is more closely related to eastern wild turkeys than Merriam’s. It also appears the California turkey was endemic to California, with a range from Orange County in the south through LA County to Santa Barbara County in the north.

Bones of birds representing all stages of development, from day-old chicks to nearly adult individuals, have been recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits, providing one of the best records of life during the Pleistocene era. Nearly 12,000 bones representing more than 700 individual birds have been pulled from the La Brea Tar pits outside of Los Angeles.

Today, it’s thought that the California turkey arose evolutionarily about 11 million years ago and went extinct 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Physical Characteristics of the California Turkey

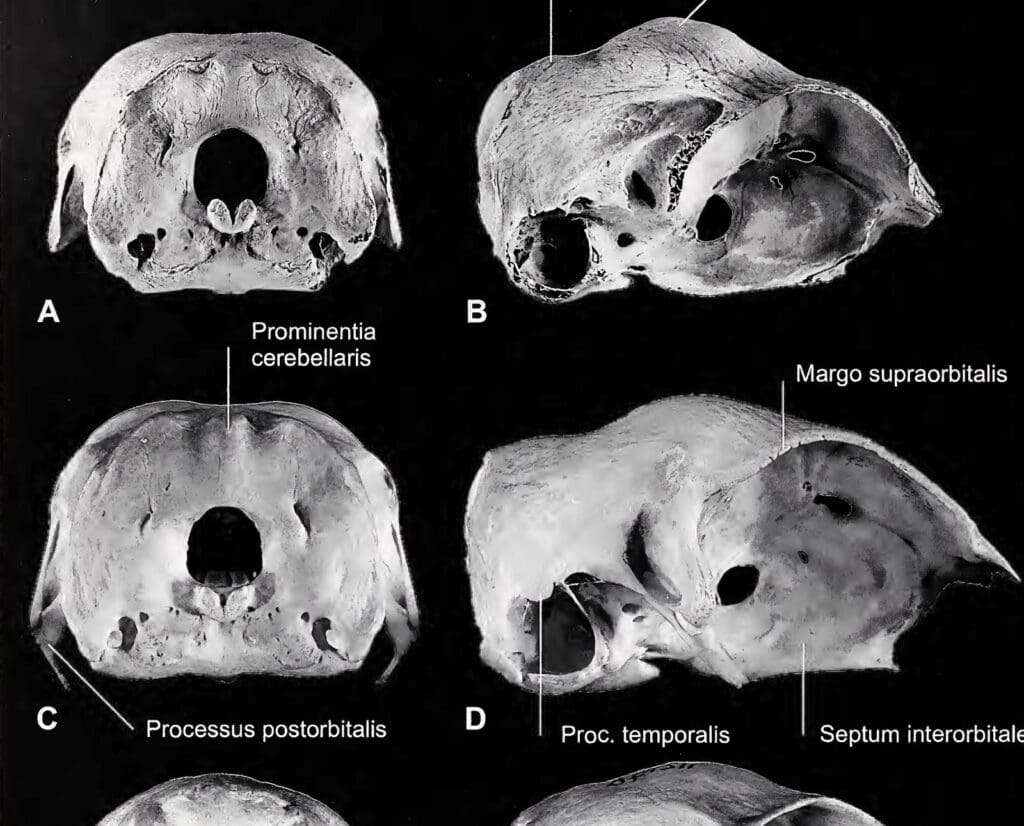

The careful assessment and analysis of thousands of different California turkey specimens allowed researchers to develop a better understanding of the bird’s physical traits and characteristics. M. californica was slightly smaller than its modern wild turkey counterparts.

One of the last major studies of bones and fossilized records of M. californica was done in 1980 by Steadman. He reexamined the bird’s skeletal information, allowing scientists to study specific bone samples from different turkey species, including M. gallopavo and M. ocellata. This work showed that the extinct M. californica shared more physical features in common with eastern wild turkeys than other modern subspecies.

Researchers from the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum suggest, “Based on the bones, the California turkey was smaller and shorter-legged than the modern wild turkey with a slightly shorter, flatter, and wider beak.” A study by Bochenski and Campbell from 2006 shows that the extinct species M. californica is most similar to M. gallopavo, with which it shares nearly half of all the character traits that were analyzed (sizes of different bones, bone ratios, etc.).

Bochenski and Campbell also hypothesize that, just like its modern counterparts, the California turkey utilized unique vocalizations to communicate with other turkeys. It may have been because of its ability to call to other members of its species that such a high number of birds were found in the tar pits. The theory is that the birds that became immobilized in the tar would cry for help, which in turn would cause members of the flock to approach, who would also become stuck.

California Turkey Predation

Much like the wild turkeys of today, M. californica had to be in a constant state of readiness, always wary of predators from the ground and air. Although there is no direct evidence, scientists from the La Brea Tar Pits hypothesize that it is likely that “coyotes and bobcats preyed upon the adults, chicks, and eggs. Smaller mammalian carnivores such as the American Badger and skunks could have also predated the nests of ancient turkeys. It is also likely that larger carnivores such as saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and short-faced bears would have also caught the occasional adult.”

Scientists hypothesize that one of the more common predators of M. californica were avian animals like golden eagles or the extinct Woodward’s eagle. The second largest number of fossilized birds at La Brea are golden eagles, which may not be a coincidence, but a reflection of the predation on the California turkey. Scientists suggest that eagles would have hunted these turkeys while they were on the ground and on the roost.

Turkeys stuck in the tar pits would have made a tantalizing treat for any eagles flying above. The theory is that the large number of golden eagle remains in the pits indicates that birds may have tried to attack the vulnerable, exposed, immobilized turkeys. When the eagles hit their target from above, they would have anticipated being able to successfully pick up their quarry and fly away with ease. However, with the turkeys themselves firmly embedded in the tar, the eagles would have struggled, often becoming tangled in the tar themselves. This incident would have left their remains to be preserved and found by scientists thousands of years later.

As paleontologists from the La Brea Tar Pit suggest, “The California turkey appears to have been a common species (based on the large number of fossils recovered). It is possible it formed an important dietary item for carnivorous birds and mammals during the late Pleistocene.“

Extinction of the California Turkey

The extinction of M. californica was not a fast occurrence but one that evolved over time due to a series of factors. Natural weather changes also heavily impacted the population numbers of this turkey. Scientists documented a steady decline in precipitation, with levels dropping significantly over a period of 100 years around 11,500 BP. A drastic change in precipitation would have had a significant impact on all flora and fauna, including the California turkey’s access to drinking water and essential roost trees.

As droughts became more frequent and extreme, water sources critical to the survival and dispersion of M. californica began to dry up. The lack of precipitation would have had a direct effect on how turkeys congregated and roosted. Not only was water essential to their own survival, but without it, their roost trees would have died or become unusable. The drought, coupled with the impact on roost trees, began to force turkeys to congregate in smaller, more densely populated areas.

Unfortunately for M. californica, predation was not limited to nonhumans. Around 12,000 BP, Paleoindian people arrived on the West Coast, which scientists believe may have put an end to an isolated and vulnerable species. The drought-like conditions made for ideal hunting conditions for early Paleoindian people, who probably quickly realized that concentrated turkeys are much easier to find and kill.

The arrival of a new, skilled, and proficient predator in the form of humans, coupled with the impact of prolonged drought conditions, spelled out the beginning of the end for California’s wild turkey. Although these birds aren’t around for modern humans to admire, if you hunt in California this year, take a minute to remember this special bird that once gobbled and clucked its way around what is now the California coastline.

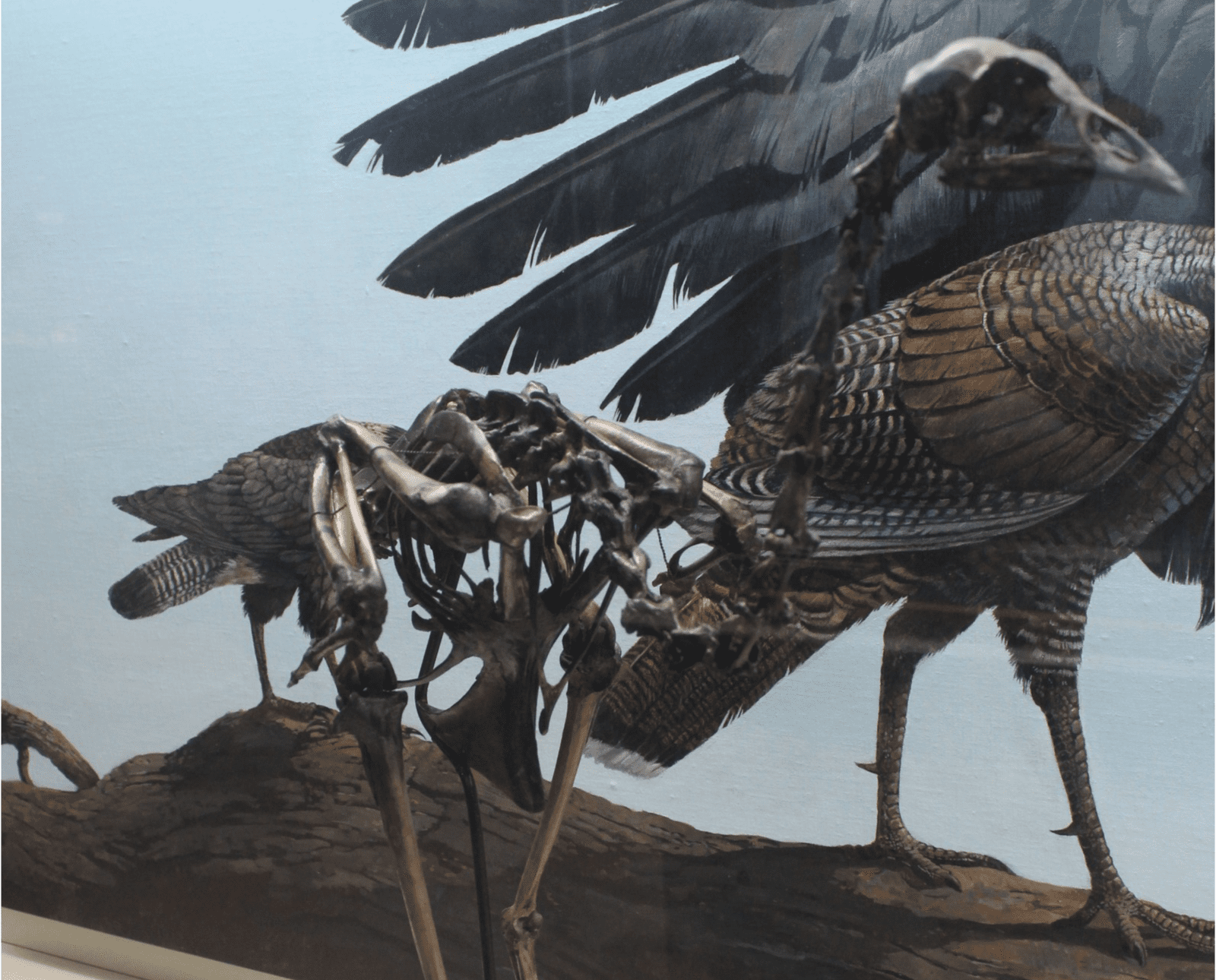

*Feature Image of Skeleton of Meleagris californica on display at the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits by Jonathan Chen

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada who spends his free time hunting and fishing in Northern Ontario with his family and Wirehaired Pointing Griffon named Clover. Before becoming a teacher, Craig was a back country guide and grew up camping and fishing. When he’s not on an adventure with his young family or planning his next upland hunt, you’ll find him introducing his inner city students to the great outdoors.