Home » Conservation » The Unfortunate Story of the Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido)

The Unfortunate Story of the Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido)

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to…

How this Eastern prairie chicken known as the Heath Hen became extinct despite our efforts to save them and the lessons we learned.

The heath hen, pronounced “hethen” (William Harden Foster 1942.), was yet another member of the grouse family. But sadly, this grouse was last seen in this world back in the 1930s. Its closest living relatives today are facing similar challenges, so what can we learn from this bird’s story to prevent it from happening again?

What Was the Heath Hen?

Under the Tympanuchus cupido species, there are three recognized subspecies: the greater prairie chicken (T. c. pinnatus), the Attwater’s prairie chicken (T. c. attwateri), and the heath hen (T. c. cupido) — the lesser prairie chicken is also related, but is a separate species. The greater prairie chicken currently exists on a small portion of its historic range, the Attwater’s prairie chicken is highly endangered and localized only along the Texas coast, and the heath hen functionally disappeared by the late 1800s.

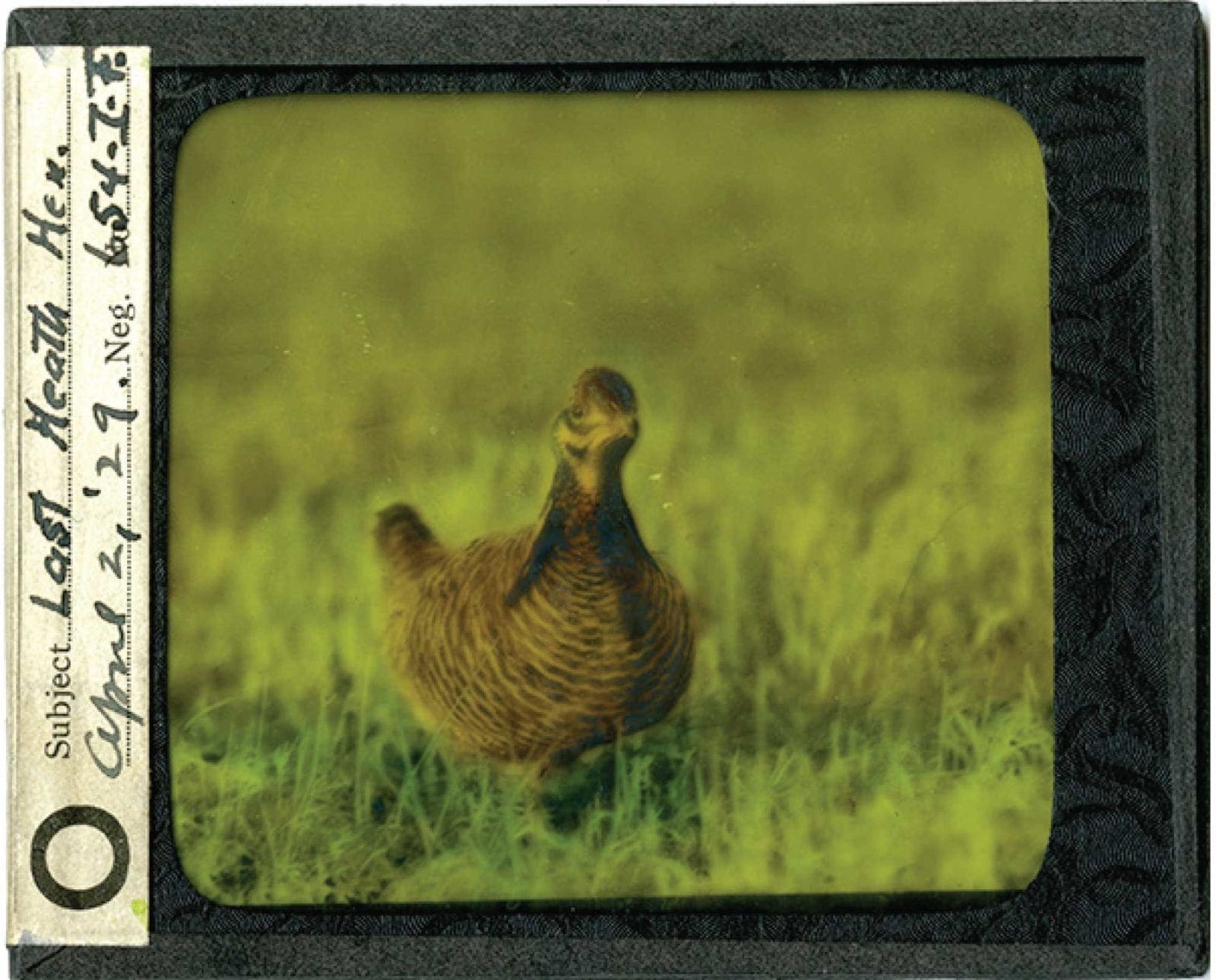

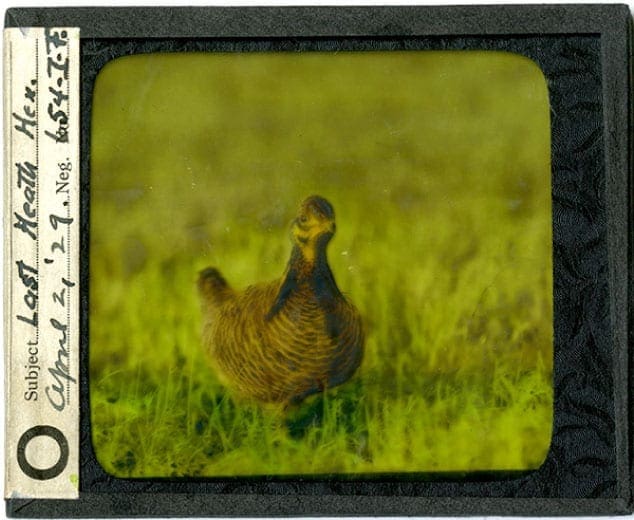

This bird was slightly smaller than the greater prairie chicken we know today, weighing roughly two pounds. Its plumage was also slightly different in that its barring pattern was generally thicker than the greater prairie chicken, and its feathers were tinged with red.

Like its close cousin (the greater prairie chicken), the heath hen was a bird that specialized in using an open landscape. But not open prairies and grasslands that we imagine for the interior of the country. Instead, the heath hen preferred sandy, heath barrens throughout New England and down some of the East Coast, where small shrubs (often of the heath family) and scrubby trees were sparsely mixed with forbs and grasses. Here, the birds were so abundant that they were an easy and staple food source for Native Americans and early European settlers.

READ: Will the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Be Listed Endangered?

Causes for Extinction

Unfortunately, populations of the heath hen were decimated on the mainland by the late 1800s, primarily due to over-hunting. Hunting bans and closed seasons did little to help. A small surviving population was protected on the island of Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts as a sort of sanctuary. In this protective isolation, the population rebounded for a couple decades and became a bit of a tourist attraction. But ultimately, the last heath hen (a male nicknamed “Booming Ben”) succumbed to extinction in 1932. What happened?

First, the habitat needed by this species was a fire-dependent ecosystem. The heath barrens were maintained and thus kept in an open landscape by somewhat regular wildfires or from fires intentionally set by American Indians. Early conservationists thought that by preserving the habitat as it was and by preventing fire, they would provide the best habitat to help the birds. Unfortunately, that just led to a build-up of fuel (e.g., grasses, wood, etc.) over time. When a fire inevitably broke out in 1916, it raged and destroyed a large portion of the habitat on Martha’s Vineyard and likely numerous nests and eggs (Edey Sr. 1998).

A string of unfortunate events further hurt the island population (All About Birds 2014). Apparently, an invasion of northern goshawks (e.g., primary predator) easily picked off the heath hens the same summer of 1916 because the habitat had been so decimated and cover was sparse. That was followed closely by a particularly bad winter in 1917, and then a disease transmitted from domestic chickens is thought to have spread. All of these events wreaked havoc on the birds and whittled the population down further.

The final nail in the proverbial coffin had to do with genetics. Because the population on Martha’s Vineyard had been reduced several times to such a small gene pool, their genetic diversity had been nearly wiped out. With no other populations to “borrow from” for captive breeding, the effects of inbreeding wiped out their reproductive capacity (i.e., sterile males), which led to a swift end.

What Have We Learned?

Much like the plight of the passenger pigeon, there are several things we could have done differently to help save the heath hen before it was too late. Hindsight is almost always clearer that way. Here are some of the hard lessons we’ve hopefully learned, and may still need to apply to other species.

One of the biggest takeaways is the importance of fire in fire-dependent ecosystems. In the case of the heath hen, most of the sandplain barrens that used to support these birds on the mainland slowly disappeared over time due to the natural process of forest succession. Without fire to set it back, heath shrubs were replaced by larger shrubs, and then trees, and finally, a climax mature forest. And when the habitat is gone, it’s almost impossible for a species to persist for long. Fortunately, land managers understand fire ecology much better these days and are applying this to current species, such as the bobwhite quail, sage grouse, and sharp-tailed grouse. If we can keep the habitat in good condition, the chance of a species escaping predation and successfully raising broods improves.

Another lesson to consider is to not put all your eggs in one basket (forgive the bird pun). By isolating the entire remaining population of heath hens on one island, they were all at-risk from whatever threat occurred there. For the heath hen, the threats were many and clustered too closely together. Biologists today try to establish populations in the same general region but separated somewhat, so that if one population takes a heavy hit, they can supplement the genetics from other populations. That being said, it’s believed that a decline in genetic diversity is likely impacting the remaining prairie chicken species, as well (Johnson and Dunn 2006).

Even though the last heath hen passed into the history books almost 90 years ago, its story can still be used for good today. As long as we can learn from their situation and apply the lessons we’ve learned since, the calls of “Booming Ben” and his cousins won’t fade away forever.

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to several outdoor manufacturers, hunting shows, publications, and blogs. He is an avid small game, turkey, and whitetail hunter from northern Minnesota and loves managing habitat almost as much as hunting. Ryan is also passionate about helping other adults experience the outdoors for their first time, which spurred him to launch Zero to Hunt, a website devoted to mentoring new hunters.

Assuming our population continues to expand, and money hungry developers continue to develop rural land, I am expecting the Ruffed Grouse to be the next casualty to add to ghe extinction list in a few more decades.

You seem to be more optimistic than I am regarding lessons learned. Fire-dependent ecosystems in the Midwest and upper Midwest don’t seem to be managed according to their biology. I remember the Seney National Wildlife Refuge fire in the 70’s and how it was supposed to have changed fire-management policy. While this may have occurred at the national level in some locales, I don’t see it being used effectively in the Wayne-Hoosier National Forest system to restore ruffed grouse habitat and many of the associated species that benefit from the same transition forest. Clear-cutting doesn’t appear to have the same beneficial effect as prescribed burns and much of these forests are reverting to climax stage where nutrient cycling plateaus. This may be good for deer and turkey, the big money-makers for state wildlife divisions, but doesn’t do much for small game hunters.