Home » Waterfowl Hunting » Hunting Ducks Over Cattle: The Trained Waterfowling Steers of Texas

Hunting Ducks Over Cattle: The Trained Waterfowling Steers of Texas

R.K. Sawyer lives in Sugar Land, Texas, and is the…

Explore the fascinating tradition of waterfowl hunting over trained steers in Texas during the late 1800s to the mid-20th century, sharing accounts of skilled hunters using oxen to approach resting waterfowl and how the practice eventually faded away due to changing laws and regulations.

Most waterfowlers have a favorite image, one that captures the essence of the hunt along one of North America’s migratory flyways. It might be sculling boats and rafts of bluebills on the Great Lakes, canvasbacks and sink boxes on Chesapeake Bay’s Susquehanna Flats, or flights of mallards navigating impossibly tight Arkansas timber. In Texas, one of the most endearing images might just be a prairie hunter shooting over a trained steer.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

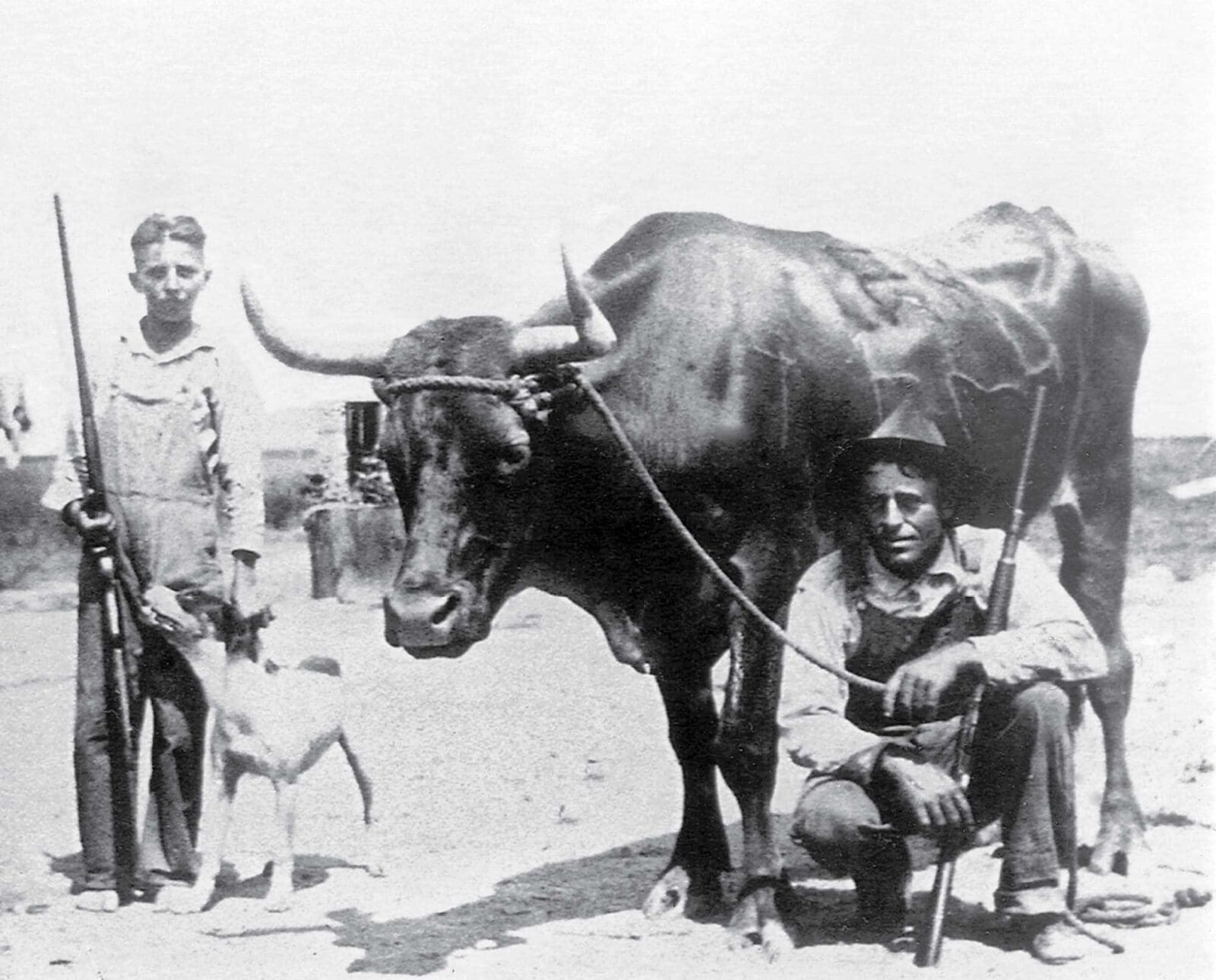

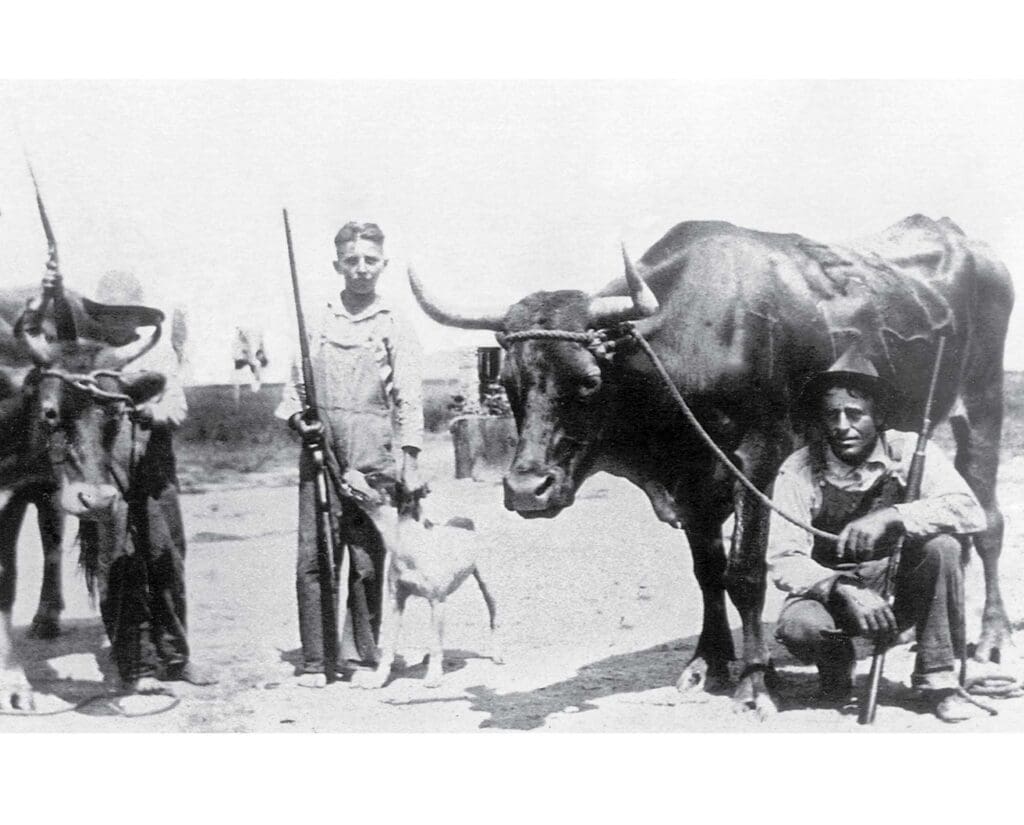

Inland and coastal Texas hunters first shot ducks over oxen during the late 1800s. The practice originated when farmers and ranchers, who saw their livestock walk to within a few feet of resting birds, began to train steers specifically for the hunt. The idea was simple enough; train the animal so hunters could walk alongside it while the owner controlled it with a halter and stick. As the ox approached resting waterfowl, it allowed one or more hunters to rest their large bore fowling pieces across its back to take the shot. A well-trained animal never stopped grazing.

Early Records of Using Steers to Hunt Waterfowl

Among the first recorded steer hunts were market hunters, who made kills of about three to four hundred ducks and geese a day behind trained oxen. To local families, waterfowl hunting in the late 1800s was not for the market or sport. It was a way to put food on the table. Steers were just a practical means to that end. When the prairie sky went black with ducks and geese, family and ranch hands hooked up a team of mules, tied the ox to a wagon, then scouted a suitable location. On the Jackson Ranch, now part of the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge east of Galveston Bay, the family wrote of steer hunts in which “the resulting slaughter of birds tremendous.”

As Texas became a hunting destination in the early 20th century, local guides kept the custom alive by introducing steer hunting to their customers. It became very popular, and at its peak, dozens of steer hunting guides were in operation in Texas, mainly in the crescent-shaped lower coastal plains between Matagorda Bay and the Sabine River.

While hunting between Houston and Galveston in the 1920s, one shooter provided a vivid description of the bovine sport: “ rented for the morning a trained ox which has been in the hunting game for years and is the chief source of his owner’s income. This animal has been trained to walk around in circles, apparently grazing, gradually coming nearer and nearer to the birds, while we kept on his far side. He can get very close in this way and we got all the duck(s) we wanted in a couple of hours, and more than we could eat. We fired several times right in the old bull’s ear but he must be stone deaf.”

Most Texas steer hunting stories are lost to posterity, but a few accounts exist from Galveston, Fort Bend, and Chambers counties, and the Katy Prairie. Once an endless sea of native grasses dotted with freshwater ponds, Katy Prairie, west of Houston, was ideal habitat for hunting over trained oxen. The first known account of steer hunting was in 1909, when Houston hunters harvested 21 geese and four sandhill cranes in just a few hours, which they stalked alongside their guide’s “intelligent animal.”

Rancher Hank Jordan opened a commercial steer hunting operation on the Katy Prairie in the late 1920s. For a fee of $5 each, hunters were loaded into wagons, then scouted for ducks in the tall grass by standing in the wagon. When a flock was located, they made “a sneak,” as it was called, in which two to three men walked beside the steer and circled the pond, closer with each pass. Hank’s grandson, Lyle Jordan, says: “Then you’d stop and let the steer keep walking. There’s nothing that has any more of a surprised look on their face than a bunch of ducks sitting there and all of a sudden they see three guys standing there with shotguns!”

Several other Katy ranchers were in business by the 1930s. Rancher Joe Beckendorff’s trained steer named Oscar was perhaps Texas’s most famous, and for years stories of his hunting prowess were circulated in newspapers. Joe did not guide over Oscar but instead leased it to eager hunters by the hunt or season. Oscar spent the 1933 hunting season on Jackson Ranch in Chambers County, earning Joe over $100, a good income in Depression-era Texas.

The Outlawing of Hunting Waterfowl Over Steers

The one constant in waterfowling is change, and steer hunting was destined to follow sink boxes, punt guns, and live decoys into obscurity when it was outlawed by the Texas Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission in 1941. Like many of America’s game laws, not everyone took immediate notice. For example, outlaw market hunters continued using trained steers into the 1950s. To keep the law at bay, they posted lookouts on windmills while piling horse carts high with ducks destined for big city restaurants. Whenever a game warden was spotted, ox and hunters quietly disappeared into the tall grass.

Sport hunters continued their use after the 1941 game law, as well. Katy Prairie’s George Nelson had a steer he called Leo, named after Texas radio personality and politician W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel. Lyle Jordan relates that although Leo was mighty hard to hide, “the game wardens never could catch his owner and his ox.”

The last available record of a Texas steer hunt was in 1949, as part of Houston sports writer Andy Anderson’s and the Katy Prairie community’s annual Wild Game Dinner for Disabled Veterans. Sponsored from 1949 until the mid-50s, it was held on the final weekend of each hunting season. It was a big event. Local landowners opened their ranches to hunters willing to donate their harvest to the benefit. State game wardens checked in participants. Ranchers guided hunters to their roost ponds. V.F.W. volunteers manned duck cleaning areas, and highway patrolmen hauled ducks to the cleaning shed.

Hundreds of ducks and geese were donated to the Naval Hospital in Houston, and local law enforcement mostly looked the other way as a few game laws were “bent” in the name of the benefit. Federal game wardens were a different story. One year, the benefit organizers got wind that federal wardens were spread across the prairie and, according to sportsman Harvey Evans, “They’re gonna make everybody have a limit of ducks.” Harvey continued, “Well, there wasn’t any way we could do that, so we sent the word to go stop some cars!” Those driving by soon posed as sportsmen, “but they did not find enough cars,” Harvey said, “so the Feds stopped our hunt right there.”

If the federal wardens had come a couple of years earlier, they might have nabbed – if they chose to – state game warden Thomas Waddell. Waddell was a fixture on those community hunts. At the first benefit in 1949, he hosted several hunters who shot their charity birds over his trained steer. It seemed like an end to an era when, according to Tom’s nephew Davis Waddell, on the last day of the event, “the ox fell over dead.”

The trained hunting steers of Texas, like the great skeins of wintering waterfowl and most of the inland prairies they called home, are gone. Through a few remaining photographs and stories, their legend lives on as a fascinating image from the pages of historical Texas waterfowling.

R.K. Sawyer lives in Sugar Land, Texas, and is the author of four historical Texas waterfowling books: A Hundred Years of Texas Waterfowl Hunting – The Decoys, Guides, Clubs, and Places (2012), Texas Market Hunting: Stories of Waterfowl, Game Laws, and Outlaws (2013), Images of the Hunt (2020), and The Tarpon Club & the Genius of E.H.R. Green (2022) available at www.robertksawyer.com.