Home » Waterfowl Hunting » History of the Sinkbox

History of the Sinkbox

R.K. Sawyer lives in Sugar Land, Texas, and is the…

Explore the rich history of sinkboxes, from their construction and purpose to their use, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

The sinkbox was effective for waterfowl hunting because it was flush with the water’s surface and nearly invisible ducks and geese, particularly to the low approach of diving ducks. Its popularity began early, three decades before the Civil War, and it remained a waterfowling tool for over a hundred years. Originating on the North Atlantic Seaboard, its use eventually encompassed all the East Coast states, the Great Lakes, Salt Lake in Utah, and south to Texas and west to California. Market hunters were the first gunners to embrace sinkboxes, and it later spread to the more intrepid of America’s sport hunters.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Description of the Sinkbox

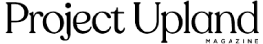

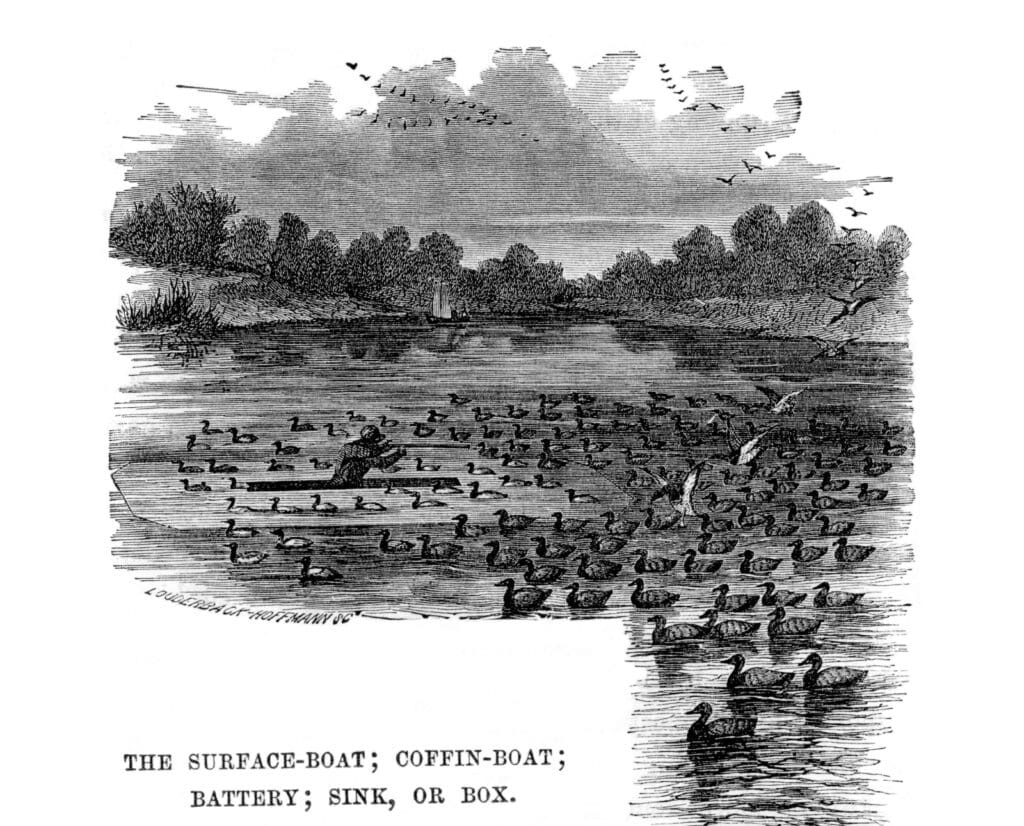

Early boxes were primitive affairs, “straight and narrow as the last sinkbox of all time”: the coffin. Initially, rigs were only set near shore, their operators fearing the deadly combination of deep water and an unseaworthy craft. The occupant was exposed to endless discomfort with only a single board for the head wing and no foot wing. Decades later, they were still uncomfortable. In Ed Muderlak’s When Ducks Were Plenty (2001), a novice box shooter concluded that a few hours of shooting were “amply sufficient time in which to acquire chills, cramps, rheumatism, and an acute attack of shotgun headache.”

Waterfowlers wondered how market gunners endured the punishment day after day. “The gunners who shoot for a living have a hard life of it,” one surmised. “They stand in these damp, chilly boxes for hours at a time in the coldest weather. They are hardy and healthy, however, and do not appear to mind the exposure.”

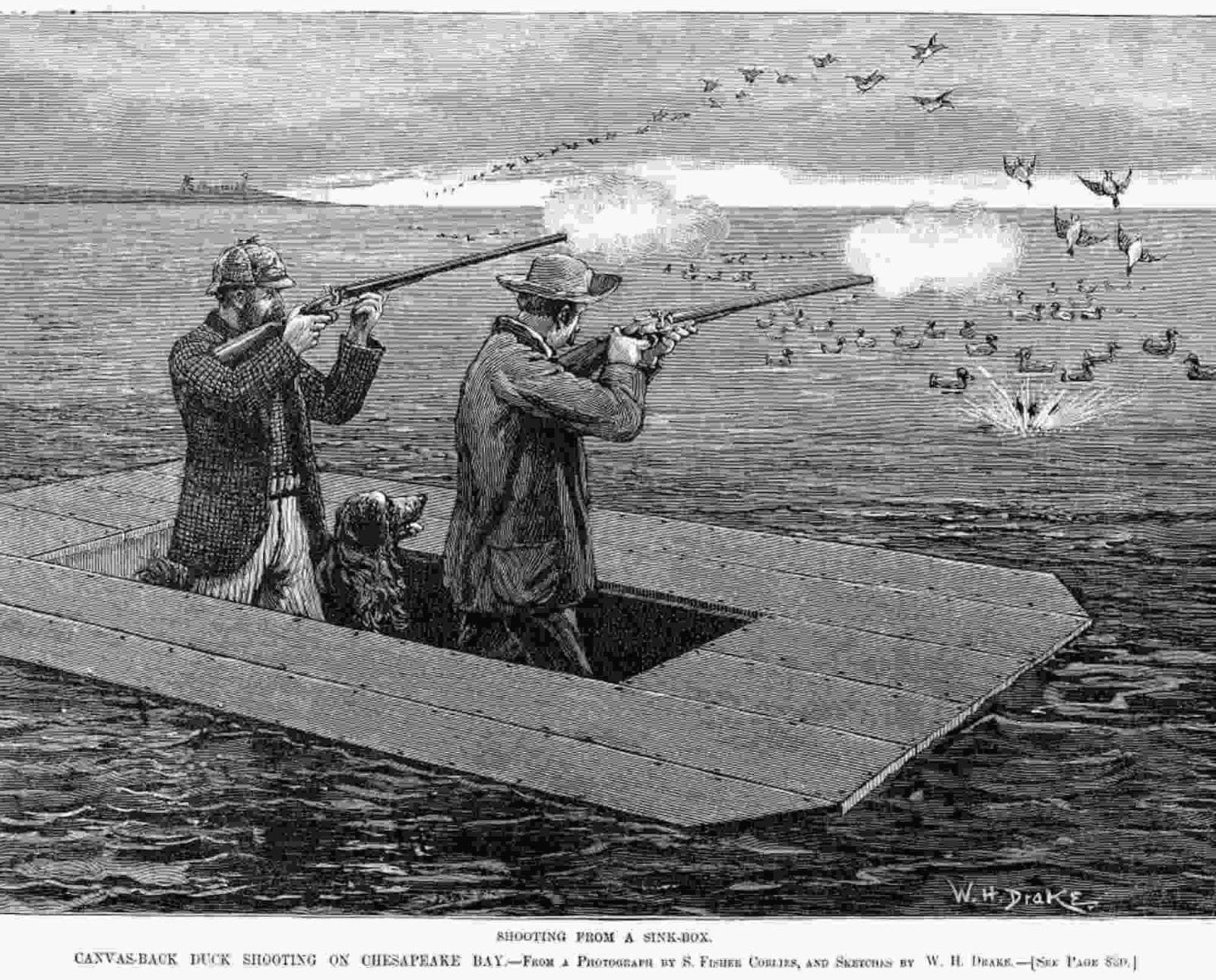

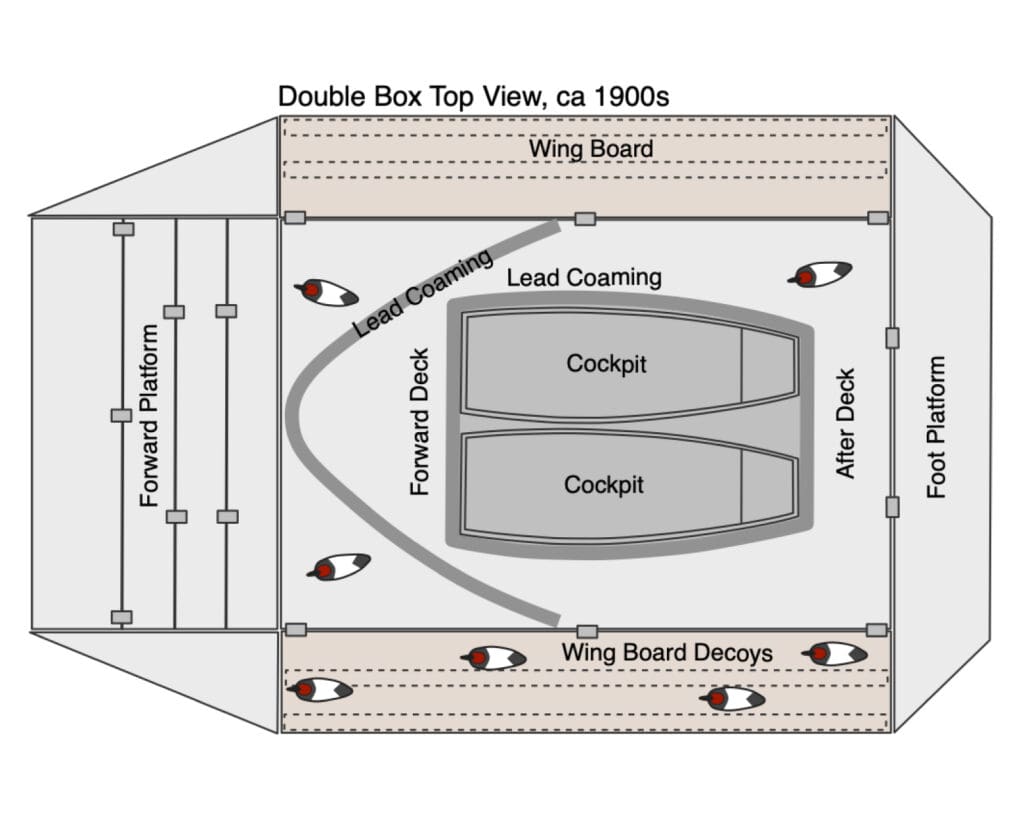

Sinkboxes were configured as both single battery boxes and double, the latter a larger contraption with two shooting cockpits (Figs. 1 & 2). In double rigs, gunners followed a “strict code of ethics” to “prevent one from getting more of the shooting than his companion.” In either arrangement, the box, or cockpit, was long, narrow, and just large enough for a person to lie prone. The cockpit was bolted to a wooden platform – the decking – and surrounded by lightweight, framed wing boards attached by hinges to the platform or its sideboards. During transport, the wing boards could be folded onto the deck, and when in use, they reduced the amount of water that washed into the box. The choice of material for the wing frames included canvas, burlap, muslin, and denim.

The cockpit decking was usually painted dull gray, the best outfitters changing its color throughout the season to match the hue of the water – yellow was added if the water was muddy, and a blue tint was preferred on sunny days. Wood strips or a coaming of iron were nailed to the deck around the cockpit that, like the wing boards, reduced the volume of water that entered the box and added ballast in the case of the iron.

Ballast was a critical part of the box. Several hundred pounds of weight was needed to submerge it to a proper depth, and it was a delicate balance between not enough ballast and too much. Lead, pig iron, and iron wing decoys were most common; the weight needed for the set was carefully calculated “according to the weight of the party occupying the box.” It took a lot of ballast. Assuming a double box with 400 pounds of man and gear, for example, 50 to 100 pounds of weights were needed in the cockpit and another 250 pounds of cast iron decoys on the deck (Fig. 3).

Sinkbox Operation

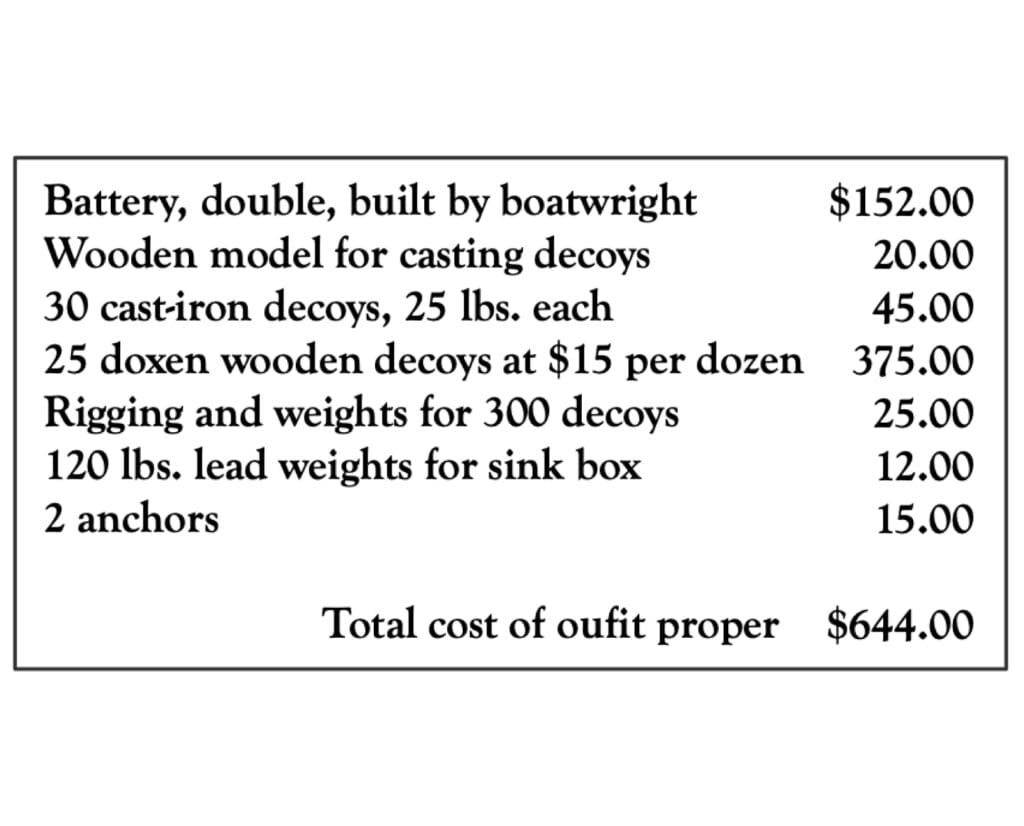

Sinkbox outfits had a lot of moving parts. The heart of the operation was a large sailing vessel called a lay boat, usually a shallow-draft scow with either two-masts or a single-masted sloop rig. Also requisite was a smaller sailboat, called a lighter or chase boat, and a tender dory or rowboat (Fig. 4 & 5). Then there was the sinkbox, plus piles of wooden decoys, iron wing decoys, stacks of shotguns, and in the days before factory-loaded ammunition, barrels of gunning powder and shot. It was an expensive proposition (Fig. 6). An entire crew of men and boys, including a seasoned captain who knew the local waterways and the habits of waterfowl, were needed to run it.

A successful outing required elaborate preparation. The dory was roped to the lay boat stern, and the lighter was either towed or was tillered on its own course. For long-distance hauls, the sinkbox was fitted with a watertight hatch and secured midship. Near the set location, the lay boat was pointed into the wind, the mainsail dropped, and the anchor secured. A halyard run-through block and tackle attached to the masthead hoisted the sinkbox from the deck and lowered it to the lighter. Next, the tender was brought alongside and loaded with decoys and other gear.

Unless the seas were heavy, the sinkbox was poled or towed behind the lighter, navigated to the set location, positioned at an angle to the wind, and then anchored at two ends before the wings were dropped. At this point, the sinkbox was a pitching, menacing rectangle on the sea, the work to weigh it down with pig iron or iron wing decoys requiring luck, skill, and agility. While the box was being tamed, the tender oarsman unwrapped six to eight feet of decoy cord from each of hundreds of decoys and set them around the shooting box. Navigation from the harbor to the gunning site and hunting preparation were done at night, with lanterns initially providing the only illumination.

The lighter then returned to the ship to fetch the shooter. Inexperienced hunters dreaded the jump from the moving lighter to the box and its mandatory dance across the sinkbox footboard. One hunter confronting the test quipped that he “resolved to drown gracefully.” In an early 1900s Field and Stream article, C.T. Hamilton offered practical advice for this delicate moment at sea. “In boarding a battery from a sharpie or small boat,” he wrote, “step on the middle of the middle of bottom board of the box and remain there, keeping your weight amidships until you’ve tested the balance.”

The lay boat anchored between a quarter mile and a mile from the box. Downwind of the shooter, the lighter or chase boat tacked back and forth to pick up dead birds and dispatch cripples. The tender handled the gunner’s needs, supplying ammunition and adjusting the box to changing sea or wind conditions. Corrections were simplest for slight wind shifts, entailing only a minor anchor adjustment from the cockpit via a rope fed through a hole in the footboard. More serious were rising seas that broke over the side, and in those situations, it was necessary to pull an anchor and allow the box to swing back into the wind. In very heavy seas, the crew had to move quickly to evacuate the shooter and save the box from sinking.

At the end of the hunt, the same volume of work went into stowing the box, decoys, and gear before a return to port. Putting out and picking up the set was hard labor. High wind, heavy seas, rain, or snow made the challenge more onerous. With freezing spray and wet hands, handling oars, sails, ropes, and the wrapping of anchor line around hundreds of decoys could be brutal. Stowing the sinkbox was also hard – while raising and hauling it aboard, its decking could act as a sail in high winds, and it sometimes filled with water.

The Sinkbox Culture

Sinkboxes may have been common throughout the US, but their epicenter was Maryland’s fabled Susquehanna Flats at the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay. About 20,000 canvasbacks were shipped to America’s largest cities each year in the late 1800s. Both market hunters and sportsmen shared the region’s waterfowl bounty between the late 1800s and early 1900s, and it was big business.

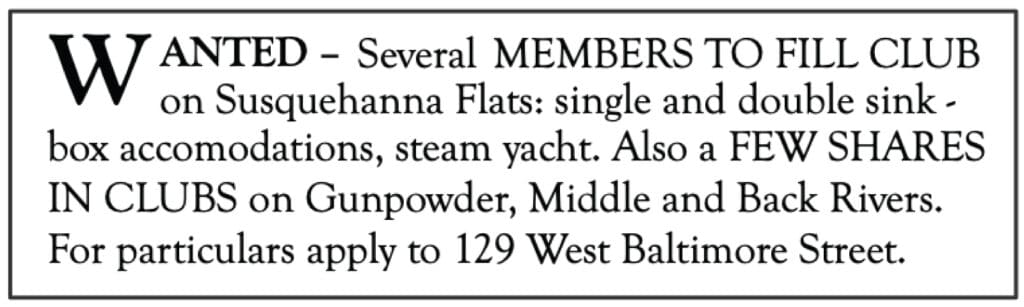

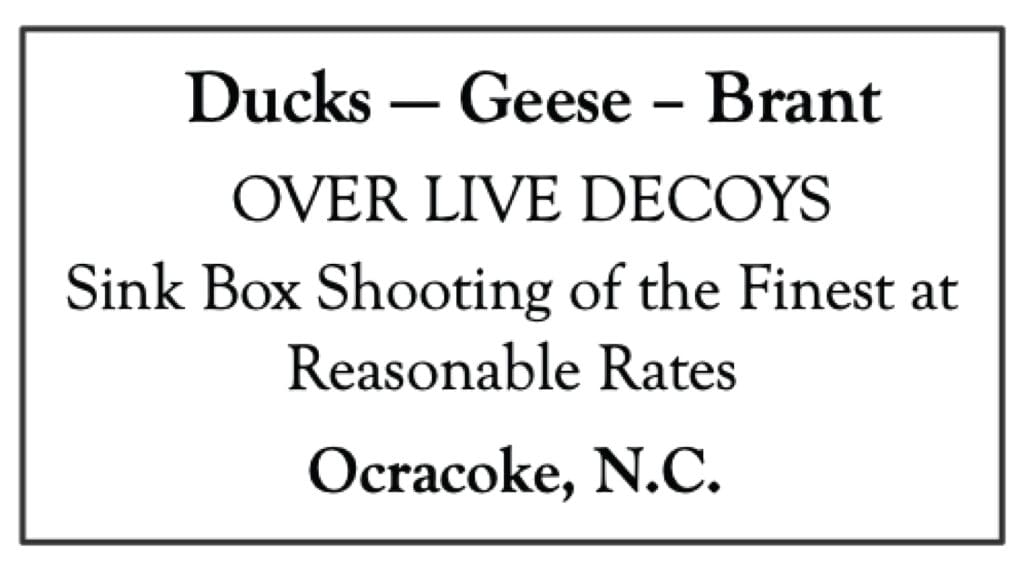

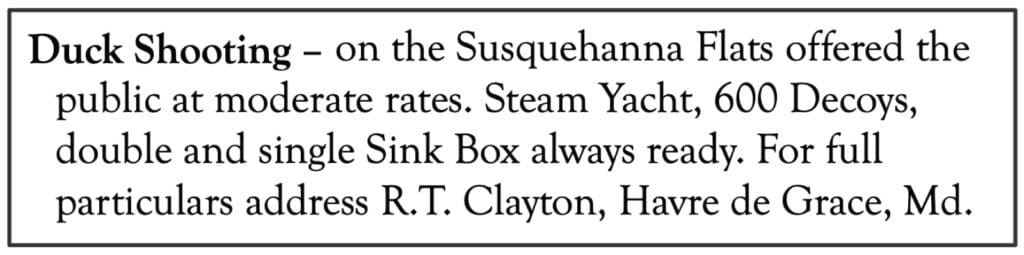

The culture of sinkbox shooting on Chesapeake Bay was so extensive that an enthusiast could purchase an entire rig by reading “want ads” in area newspapers. One listing, for example, offered a “complete outfit for gunning, consisting of steam yacht, double sinkbox, and 500 decoys.” In 1877, a retiring Bay hunter advertised a 55-foot scow, sinkbox, and 259 decoy ducks “all in complete trim ready for fall gunning.”

They were also considered important assets in 1800s real estate transactions. In addition to acres of waterfront land and fine estate houses, the listing of a lay boat, decoys, and a “handsome shooting box” often assured a quick sale. A Philadelphia businessman who advertised the sale of his “ducking farm” near the mouth of Maryland’s Elk River promoted its advantages as “three shooting points and sinkbox privileges.” For the purchaser who didn’t dally, they could profit from his orchard ripe with fresh peaches.

Duck clubs throughout the Eastern Seaboard attracted more monied members if they shot from sinkboxes (Fig. 7). In the 1920s, a Virginia club ran this advertisement:

Now organizing – Has few shares for sale. Membership limited. References required. Sinkbox and Point shooting for canvas back and red head ducks. Strictly high-class proposition.

A Place in History

As Americans began to appreciate the role of unregulated hunting on natural resources, sinkboxes moved to the center of the debate. Legal market hunting was ended by the 1913 Federal Migratory Act and 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty, but they did not prohibit the use of sinkboxes. The final blow was the Dust Bowl drought of the early 1930s when North America’s waterfowl populations were in an alarming freefall. The federal government’s response was quick, mandating drastic limits on the number of birds that could be killed per day, banning of live decoys, and prohibiting the use of a sinkbox. The numbers of waterfowl in America would never again justify lifting the sinkbox ban, its place in history assured as “the most effective contrivance for the taking of wild ducks.”

How Market Hunters Operated Sinkboxes

A sinkbox was, really, just a duck blind. Yet to follow the words of those who gunned from them, you wouldn’t guess it. During its day, the half-sunken, coffin-shaped blind was the subject of hundreds of articles in outdoors periodicals and even non-sporting journals such as Life, Look, McCall’s, and Leslie’s. With sentences colored by adjectives and flavored with romance, the authors, it seemed, wanted readers to feel like they were in the box with them – sensing the splash of cold water creeping down their necks and witnessing the birds they saw passing just a few feet over their heads. For them, the sinkbox was the only way to pursue ducks, and when it was outlawed in the places they hunted, they quit duck shooting.

Modern writers and historians are still captivated by sinkboxes. Harry Walsh brought its legend and lore to a new generation in Outlaw Gunner (1971) and, more recently, C. John Sullivan provided an authoritative history in Waterfowling on the Chesapeake, 1818-1936 (2003). A few sinkboxes remain to posterity in personal collections and museums, such as the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum with its curated sinkbox exhibit and the unique decoys dedicated to this ducking outfit.

The 1914 Century Dictionary defined the sinkbox as “a battery for wild-fowl shooting.” The terms sink boat and battery were used interchangeably with sinkbox, and almost as often (Fig. 8). According to Harry Walsh, in Outlaw Gunner (1971), the first sinkbox was built and used in New York’s Long Island as early as the 1830s. A Field & Stream article from the 1910s credits Havre de Grace market hunter Bill Dobson, in 1850, as the first to operate a sinkbox on the famed waters of the Chesapeake Bay’s Susquehanna Flats.

In its day, purist gunning aficionados groused that sinkboxes were the tool of the market hunter, but that was only partly true. The market hunter was simply better at it than anyone else. Less cynical sportsmen studied the commercial shooter’s prowess and tried to learn his ways. Mostly they failed, but along the way, they also fell under the trance of “the most effective contrivance for the taking of wild ducks.”

The effectiveness of the sinkbox was due to the shooter’s position at water level, with nothing that could flare decoying birds “until he raises up to fire at them.” Early boxes were primitive affairs, its occupant exposed “to endless discomfort and danger from the wash of water.” Their rise to fame was slow. By the early 1860s, only six or so gunners employed the rig on what would become the world’s sinkbox epicenter – the Susquehanna Flats, or just “the Flats.”

Boxes were configured as single battery boxes (Fig. 9) and double, the latter a larger contraption with two shooting cockpits. In either arrangement, the box, or cockpit, was long, narrow, and large enough for a person to lie prone. The cockpit was bolted to a wooden platform and surrounded by lightweight, framed wing boards attached by hinges to the platform or its sideboards. Several hundred pounds of weight were needed to submerge the box properly, and iron wing decoys became a common and practical ballast (Fig. 10).

Decoys and Guns

The earliest sinkbox decoys were nothing more than painted duck outlines on the deck or sideboard frames with a carved, wooden duck head inserted into a hole with a dowel. These crude decoys evolved into lightweight wooden “wing decoys” that were flat on the bottom. Cast iron ballast decoys were also flat on the bottom, their weight distributed around the sinkbox deck. Popularized in the early 1880s, they weighed between 20 and 30 pounds each. Experienced gunners knew to tie the iron decoys to wooden ones – in an emergency, they could be tossed over the side but wouldn’t sink to the bottom of the bay.

Floating decoys were arranged in “stools” around the shooting box, their numbers varying from a low of about 200 to as many as 700. Dozens of local decoy carvers supplied the Flats sinkbox fleet and its gunning clubs. Unintentionally, the men who shaped those decoys created an art form eagerly sought by collectors today. John “Daddy” Holly and John Black Graham are considered the originators of the Susquehanna Flats carving style, their work dating back to before the Civil War. The names of carvers engraved on the bottom of their stools might have been theirs, the gunning clubs that purchased them, or, for sinkbox rigs, the syndicate lay boat or steam yacht.

The shotguns of choice in the 1850s and early 60s were muzzle-loading, double-barreled guns, with eight to ten gauges most popular. Great dexterity was required to load these ponderous weapons in the confines of a sinkbox. A Field & Stream writer in the 1870s said that a skilled waterman could load a black powder gun “in about the time it now takes a novice with chilled fingers to load from the breech.” The evolution from black powder muzzleloaders to repeating guns with pre-loaded ammunition was a major catalyst for the growth of sport hunting. When Browning developed the first semi-automatic shotgun at the turn of the century, it revolutionized shooting technology. No special skills were required to load it or fire five factory-loaded shells in rapid succession with just a trigger pull.

Shooting from the Box

The sinkbox enabled access to shooting locations far from shore, and because it was flush with the water surface, it was nearly invisible to the low approach of diving ducks. But, for the novice, the initial sinkbox experience could be disarming. There was the solitude, the emotion felt as soon as the flapping canvas sails of the set boat disappeared on the horizon. Then there was the sensation of lying flat on their back, waves lapping close to their ears, gazing straight up at the sky.

One problem with the sinkbox was that almost no one could instinctively shoot from it. Stories abounded of the usually proficient marksman unable to hit even a single bird on their first outings. One expert marksman attributed his initial poor results to shooting “from a recumbent position in a floating box which is constantly swaying with the swell of the tide,” he summed up his experience as “sufficiently mortifying.”

There were other wingshooting challenges besides the bobbing box. One was that the shooter, situated below the water line, had difficulty judging the distance of decoying birds and then rising from its painfully cramped quarters at the proper time. Right quartering shots were difficult for right-handed shooters, although seasoned shooters knew to “throw a leg up over the box when a duck gets abeam of the shooter.” There was also a lack of familiarity with handling two or more guns in the shooting box and remembering to point their muzzles over the rig’s side. Accidental discharges were common, and they were known to sink the rigs.

There were dangers to sinkbox shooting. Boxes sank from waves, the weight of spray that turned to ice, or shotgun blasts through the box below the waterline. The advice was offered that if the box “ships water faster than it can be bailed,” throw over some deck weight – the iron decoys – to give the battery more freeboard. Then signal the helper boat. As a last resort, “If you are bound to sink, stick to her. Get a foothold on the deck and weather the storm until you are rescued.” Not everyone was rescued. In 1880, an insurance company listed the cause of death of one policyholder as “the gun of a man out duck hunting in a sinkbox exploded, stunning him and tearing a hole through the bottom of the sinkbox, which filled and sank before the hunter recovered consciousness.”

Sinkbox Geography

The use of sinkboxes was recorded in nearly every Atlantic Seaboard state (Fig. 11), the Great Lakes, Salt Lake in Utah, and south to Texas and west to California. While popularized by Susquehanna Flat market hunters to kill mostly canvasbacks and redheads, as its geographic reach increased, so did the quarry, which came to include bluebills, goldeneyes, buffleheads, ruddy ducks, swans, geese, and brant. Only occasionally was it suitable for “high-flying ducks,” such as black ducks and mallards.

A Connecticut marketman in the early 1870s operated a sinkbox rig in Long Island Sound almost exclusively for brant. Sporting a 16-pound black powder gun, he waited until his spread was “densely packed with brant,” then made his shot on the water, often killing between 40 and 60 brant with a single discharge. Two prolific sinkbox operations in coastal Texas targeted redheads, canvasbacks, occasionally geese, and even whooping cranes. Swan shooting from sinkboxes was popularized on North Carolina’s Currituck Sound. As canvasback numbers dropped during the 1890s, some of the area’s market hunters turned to ruddy ducks, anchoring sinkboxes in channels along their flight path.

But it was Maryland’s fabled Susquehanna Flats that made the sinkbox famous. Located at the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay, plant-boosting nutrients from the Susquehanna, Northeast, Elk, Bohemia, and Sassafras rivers created ideal growing conditions for wild celery grass and other submerged aquatic vegetation, producing 25,000 acres of the best ducking grounds in the world. About 20,000 canvasbacks were shipped from Have de Grace to America’s largest cities annually during the late 1800s. While prices fluctuated with demand and availability, market hunters were usually paid $1.50 for the red, black, and white diver. Redheads fetched 80 cents and black ducks 40 cents a pair. It was big money, and Flats watermen did not squander the opportunity.

The best-known early-era Flats hunters were Bill Dobson, Jess Poplar, John Mahan, Ben Dye, William Brumfield, William Burroughs, and Henry Cowden. On good days, most of these men returned to the Havre de Grace docks with kills of 200 to 250 birds. The shooting prowess of Flats market gunners with a double-barrel shotgun “was almost uncanny,” and the daily duck score of the Flats market men was the stuff of legends. Hunter names and harvest numbers were published in area newspapers and followed by every sporting enthusiast of the day.

Bill Dobson set the Flats record with a shoot of more than 500 redheads and canvasbacks, despite the handicap of just a single black powder gun. He started the morning with two – but left an oiled rag in the barrel of one and blew it off. The lay boat crew that witnessed his shooting exploits reported flocks that decoyed in groups of 50 to 100, and he killed between five and a dozen ducks with every round. Using his first breech-loading shotgun, William Brumfield held the title for the second-best score – 316 ducks, his tally including 174 canvasbacks. Flats marksmen were so proficient that even an aging Captain Frank Jackson, who was blind in one eye, could fire two shots and kill five to seven birds every time.

Sinkbox Syndicates

Their shooting may have been revered, but the market men were often at odds with a growing breed of hunter – the wealthy sportsman. The first gentlemen sportsmen put down stakes on the Flats just three years after the final cannonades of the Civil War. Their numbers were initially small – only three sinkbox syndicates in 1868, all from Philadelphia. The monied sportsmen made their presence known immediately, convincing the Maryland legislature to restrict where sinkboxes could be used and to provide a “revenue cutter” for enforcement.

Limitations on the watermen’s livelihood were not taken very well. After the locals resorted to a litany of unpleasant retaliations, the usurpers wisely had the offending law repealed. The cultural disparity between local watermen and the more urbane gunners would continue, resulting in an uneasy co-existence at best and, at worst, a war of sorts between them.

When canvasback numbers decreased for a few years in the early 1870s, Flats market men blamed sport hunters while, for their part, sportsmen blamed the greed of the market hunter. A decade later, gunners were still grumbling about wintering canvasback numbers, but more often, the complaints were more about the number of sinkbox operators pursuing them. There were so many, a Baltimore Sun editor carped, that it was impossible to “secure an eligible place without getting into dangerous proximity” to other sinkbox operations. The Havre de Grace sinkbox fleet had grown from about 40 “professional outfits” during the late 1870s to, by some accounts, nearly a hundred in the mid-1880s.

Syndicates ran their hunts from finely fitted and appointed “gunning yachts,” and some hired the best-known area market gunners as their captains. The scow Reckless was the largest and “best-fitted sporting craft,” carrying a double and single box and 500 decoys. A Philadelphia stockbroker owned the Carrie and hired legendary Havre de Grace wingshooter Jess Poplar (Fig. 12) to pilot her. A New York judge owned the Jno. Russell. Other yachts that plied the waterways included the Lillie, Widgeon, Mischief, Susquehanna, J.W. Bell, and the steamer yachts Mignon and Evadne, captained by Washington Barnes.

Sinkbox Outfitters

Sport hunters not wealthy enough to own their own syndicate could hire a local market hunter (Fig. 13) as a guide. On the Susquehanna Flats, market men who doubled as guides had a unique pricing scheme – they charged about what they would have made if their birds were sold in the marketplace. The opening week of ducking season was always expensive. The cost per day throughout the late 1800s was usually about $100. The price declined for the remainder of the season, with watermen charging between $30 and $50 a day.

By the 1910s, the rate was as much as $200 per day for the opening week and rarely less than $50 as the season progressed, although the cost could be shared “by three or even four sportsmen taking turns in the box.” The increased fee was not only a result of demand but also because of technology. With the advent of the gasoline engine after the turn of the century, watermen were burdened with the expense of fitting their lay boats with “auxiliary power” and replacing single-masted lighters and the wooden oars of the dory man with naphtha or gasoline-fueled launches. The outlay to own and operate the outfit increased proportionately, “entailing an expenditure of $2,000 or $3,000 that usually constitutes the entire fortune of its owner.”

The Coming of Laws

As Americans began to appreciate the role of unregulated hunting on natural resources, sinkboxes moved to the center of the debate. Proponents of its regulation cited the tremendous kills enabled by the rigs, the unceasing disturbance of roosting and feeding grounds by the sinkbox fleet, and the never-changing theme that blamed market men and their large, financially motivated harvests.

Before the 1913 Federal Migratory Act transferred the authority for migratory wildlife protection to the federal government, individual states and counties drafted, promulgated, and enforced their own wildlife laws. Laws prohibiting sinkbox shooting were passed in New York in 1839, Ohio in 1852, and New Jersey in 1879. Connecticut outlawed sinkbox shooting in 1882, although only on the “feeding grounds.” Sinkbox batteries were outlawed in “Washington Territory” by 1887, and in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota by the 1890s.

Although they were well-intended, game protection by individual states was wildly inconsistent. For example, according to C. John Sullivan, Maryland enacted 59 different migratory bird laws between 1832 and 1936. Because each regulation was specific to different counties, rivers, creeks, and tributaries, the slightest misjudgment in maritime reckoning could turn a law-abiding fowler into an outlaw.

One of the most far-reaching of Maryland’s “Public Local Laws” was passed in January 1872. Covering just two counties adjacent to the Susquehanna Flats, much of its mammoth 23 sections covered sinkbox regulations. There was a lot to digest. The hunting season was limited to November 1 to March 31, but the sinkbox fleet could only shoot on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Nighttime shooting was outlawed. No sinkbox was allowed closer than half a mile to shore. The shooting grounds – defined by a line triangulating between shoreline points, islands, and lighthouses – were closed to all boat traffic before 3 a.m. Further, hunters were required to purchase an annual $20 sinkbox license, the proceeds used for enforcement by “a board of special police.”

Although the 1913 Federal Migratory Act and 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty ended the era of legal market hunting, they did not prohibit sinkboxes. Most states, however, had already banned them by then. Maryland did – everywhere except the Susquehanna Flats.

The Use of Sinkboxes Ends

North America’s waterfowl populations were in an alarming freefall during the early 1930s. This time, no one could place the blame on the guns of the hunter. Instead, the cause was habitat destruction on the Great Plains of the US and Canada from wetlands drainage, agriculture, and a seven-year drought that came to be known as the Dust Bowl. The conservation message was delivered as a series of solid black walls of air-borne topsoil that crossed the country, at times reaching as far as the East Coast.

The federal response to the “waterfowl emergency” was swift. President Franklin Roosevelt created the New Deal Conservation Agency and appointed influential J.N. ‘Ding’ Darling chief of the US Biological Survey. Darling and others laid the foundation for today’s science-based approach to migratory bird management, including waterfowl surveys, wetlands restoration, and establishing waterfowl sanctuaries he called “duck ports.”

Funding was enabled by the first Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp – the Duck Stamp – in 1934, and the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act.

Part of the 1930s federal response was to implement more rigorous hunting regulations. In 1935, drastic limits were placed on the number of birds that could be killed per day. Other new laws banned the use of live decoys. Another edict prohibited the use of a sinkbox.

For nearly a hundred years, the November start to the ducking season was eagerly anticipated by the Flat’s sinkbox fleet. But that was not the case in the fall of 1935. After the sinkbox ban, some hunters stored their rigs in sheds or barns, optimistic the law would be lifted. Others stacked them in burn piles along with discarded shad nets and old crab traps. In 1936, the shooting of canvasbacks and redheads was outlawed entirely. They would be made legal again, but their numbers would never again justify the expense and effort to set a sinkbox, “the most effective contrivance for the taking of wild ducks.”

R.K. Sawyer lives in Sugar Land, Texas, and is the author of four historical Texas waterfowling books: A Hundred Years of Texas Waterfowl Hunting – The Decoys, Guides, Clubs, and Places (2012), Texas Market Hunting: Stories of Waterfowl, Game Laws, and Outlaws (2013), Images of the Hunt (2020), and The Tarpon Club & the Genius of E.H.R. Green (2022) available at www.robertksawyer.com.