Home » Waterfowl Hunting » A Brief History of European and North American Duck “Decoys”

A Brief History of European and North American Duck “Decoys”

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was…

Whether referring to physical structures or fake ducks, duck decoys have been used to hunt ducks for centuries

Have you ever gone down an internet archive rabbithole? I sure have. While poking around some 125-plus-year-old digitized books in search of sketches of ducks, I found a waterfowling book published in England about duck decoys.

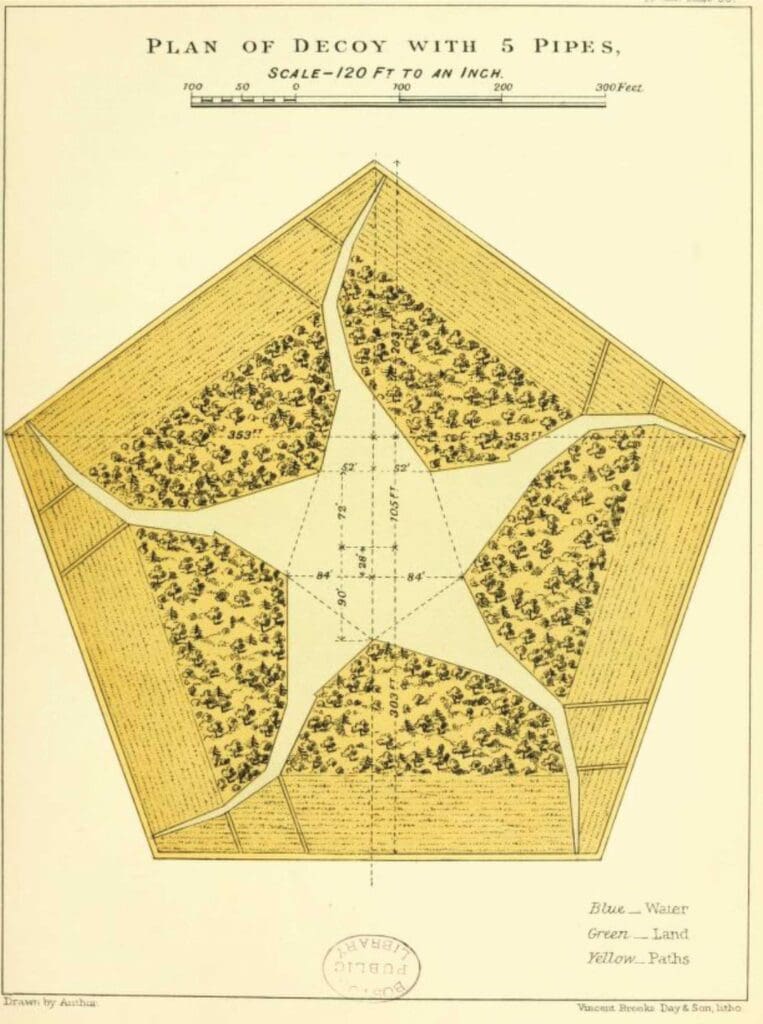

Perfect, I thought to myself, I bet there’s going to be some really beautiful decoy illustrations in here. However, after flipping through the first few pages, all I found was swirling images of circular ponds with tentacle-like fingers branching off of them. Confused, I started researching European duck decoys. As it turns out, “duck decoy” means something completely different across the pond than what it does in the United States. Instead of fake ducks, duck decoys are live traps for ducks.

When did the term “decoy” cross the Atlantic and become a word with an entirely different meaning? “This is a question I’ve been trying to answer myself,” said Nathaniel Heasley, the Curatorial Co-Ordinator for the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum in Maryland. Even if we may not have all the answers yet, comparing historical European methods of waterfowling with those practiced in the United States is worth exploring.

Elements of Duck Decoy Structures in Europe

“The popular theory is that the term decoy comes from the Dutch ‘de kooi,’” said Heasley. In Dutch, ‘de kooi’ is pronounced like “decoy” and means “the cage.” This makes complete sense when considering that Europeans built large, cage-like nets over shallow fingers of water that would drop down and capture live ducks. The Book of Duck Decoys, Their Construction, Management, and History, written by Sir Ralph Payne-Gallway in 1886, explains these structures in detail.

Sir Payne-Gallway writes that “pipes, hoops, netting, the pond, water supply, landing and banks, screens, tame decoy ducks, dogs, and food” are essential to a functional duck decoy. In his book, he also refers to live ducks within the duck decoy structure as “decoys.”

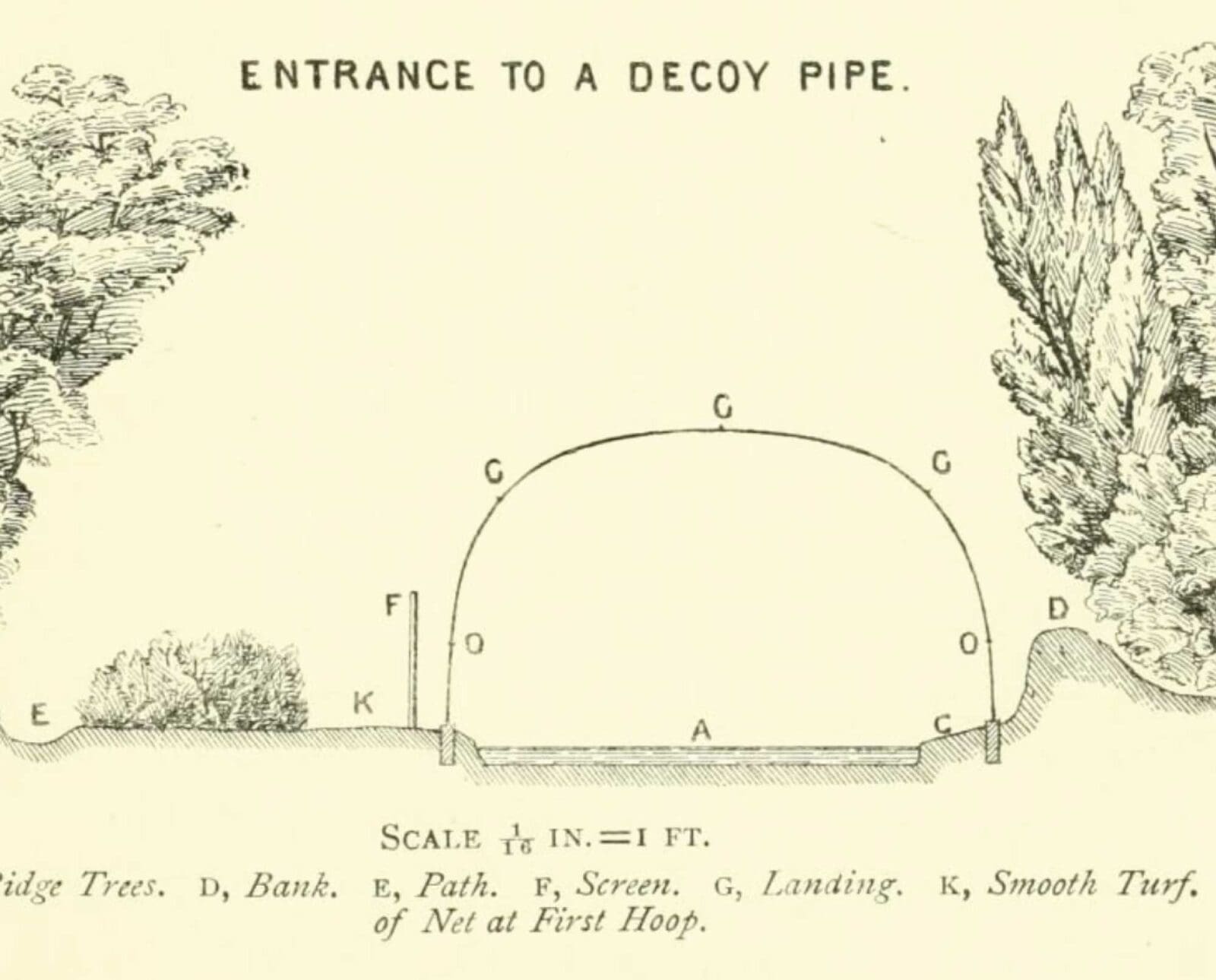

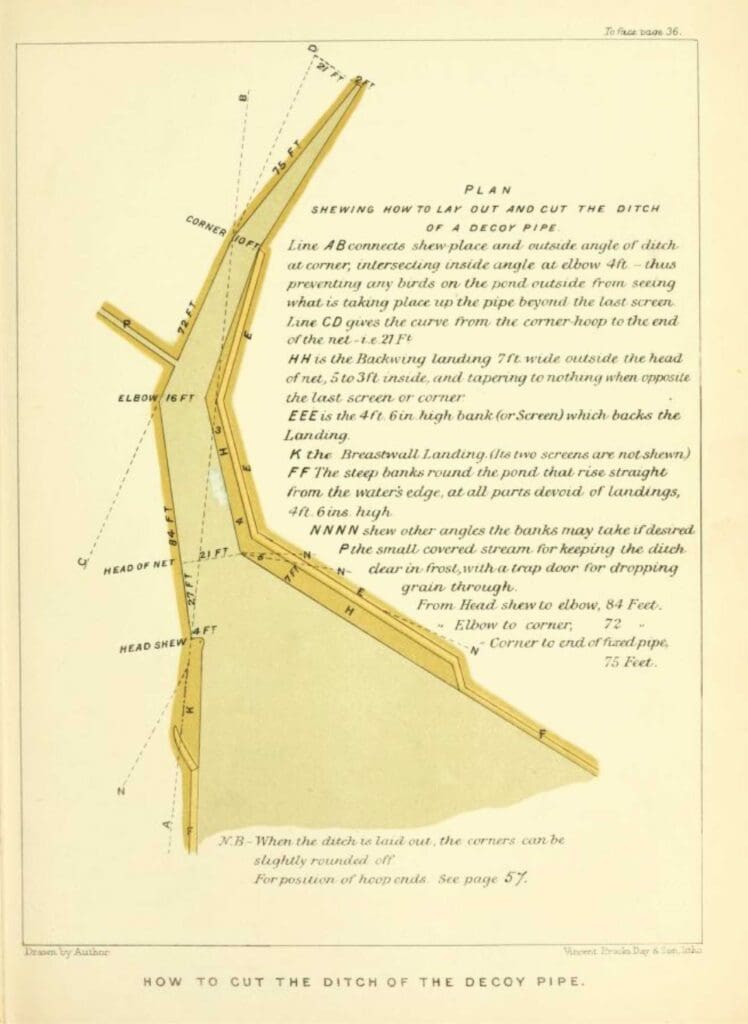

“A Decoy is like an organ,” he wrote, “it cannot be played on till the pipes are perfected.” Pipes are the narrow fingers of water that extend from a main pond. Decoy pipes, he argues, are the most important part of a structural decoy. They must be placed widely, evenly, and far away from trees so that lots of sunlight can still get through the netting laid overtop of them, otherwise wild ducks will be too nervous to enter the dark cage. “As Decoy-men say, to drive ducks well the latter must see ‘out of doors,’” said Sir Payne-Gallway. In addition to natural overhead lighting, both openings at either end of the decoy must also be well-lit.

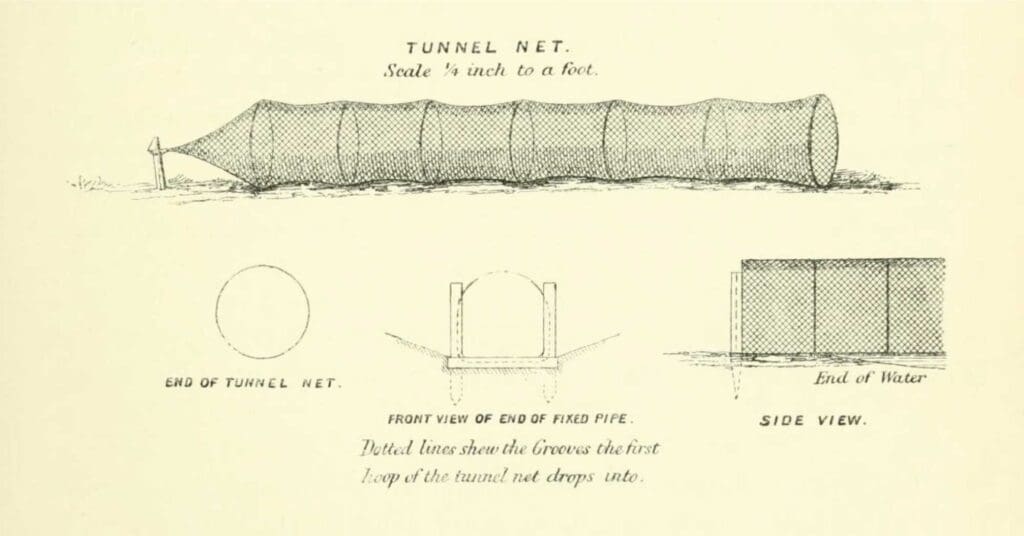

Round iron hoops arch over each pipe. The hoops get smaller in diameter the deeper into the pipe they are placed; Sir Payne-Gallway explains that the first 12 hoops should be one inch in diameter, the next 14 hoops should be ⅞ inches in diameter, and the remaining hoops that run the length of the tail end of the pipe should be ¾ of an inch. Each hoop is made up of two or three parts, and each part is either welded together on the ground or attached via bolts. Typically, the last few hoops near the tail end of the pipe are one piece.

Once each hoop is in place, netting is then “lashed to a stout wire or light iron rod running from hoop to hoop.” The net is tied off at the far end of the pipe so that wild ducks can’t escape when ushered into the decoy. Sir Payne-Gallway recommends that the netting is made from handspun hemp that’s ⅛ inches thick and coated in “Stockholm tar.” He warns that if your netting is too thin, wild ducks will fly upwards, attempting to break through the netting instead of swimming deepr into the trap. “I do not approve of wire, though more lasting,” he writes, “as in a strong breeze it sings a tune, and I have often failed to catch ducks for no other reason.”

When it comes to water, the central pond and its water supply come into play. Europeans often referred to the tranquil, one to four acre ponds as “decoy ponds.” Ideally, wild ducks won’t notice its net-covered fingers until they land in the pond. The depth should be 2.5 to three feet deep and shelve to two feet at the edges. Fresh water should flow in and out of the pond away from the pipes, but Sir Payne-Gallway advises that a sluice or small channel should run fresh water down the main pipe, too. “A strong flow through a pipe, by means of storage water and a sluice, that can be kept for emergencies, such as during a hard frost, is invaluable,” he said. “It will prevent ice forming at the pipes’ mouths.”

The “chairs for the ducks to sit down on,” also known as the landings and banks of a duck decoy, require a specific arrangement. According to Sir Payne-Gallway, the shores of a decoy should slide into each pipe. “To tempt the fowl to come ashore and rest on these particular landings, they must be level with the water’s edge, nicely turfed, smooth, and evenly sloped, and larger in space just outside the mouths of the pipes than else-where, and especially so, as I have just said, on the left-hand side of the pipe’s entrance looking up it,” he wrote. Additionally, a steep, four to five foot bank should be built all along a duck decoy except for where one wants the ducks to land. If this abrupt bank can’t be made out of soil, then a four foot tall wooden or reed fence will suffice.

Today, decoy screens are called blinds. Decoymen used screens to hide themselves and their dogs from detection. Just like the other elements of a duck decoy structure, the screens were built to very specific measurements. Each screen also has a “dog-jump” where the dog can exit and enter the screen.

Tame “decoy ducks” were used to entice wild ducks to enter a decoy. These ducks were crosses between wild ducks and “small brown farmyard” ducks. Decoymen used the same 20 to 30 live decoy ducks as long as they could. As a result, they had no fear of the decoy structure, the decoymen, or the duck dogs. This built confidence in wild ducks as they flew over and considered landing in a duck decoy. Tame ducks are fed inside of the decoy, too. “They are always fed in the pipe itself, and only get a good meal in the evening,” wrote Sir Payne-Gallway. “They soon learn to swim up a pipe fearlessly.”

The final element to a solid, functional decoy is food. Wild ducks are “tethered by tooth,” and scattering fresh food around the banks and landings each night is critical. Bruised oats, buckwheat, oiled hemp seeds, malt grains, wheat, maize, acorns, and coombs were the most common foods used. Coombs are sprouted barley that’s screened off malt. Additionally, the way the grain is thrown is more important than the types of grain used to bait ducks. Fresh grain should float on the surface of the pond and be visible to ducks flying over.

Building duck decoys was no quick task. However, they were food-procuring tools used across Europe for centuries. “These structures can be confirmed to have been used in both England and Holland as early as the reign of Charles II, as they are mentioned by name in the journal of one of his Court members who traveled through Holland,” said Nathaniel Heasley.

The Dog’s Role When Decoying Ducks

Dogs were also an important part of live-trapping wild ducks via decoys. Sir Payne-Gallway used dogs that were about one-third smaller than a fox and red or yellow in color. Some decoymen kept dogs of each color, and the decoy ducks were trained to like one dog and dislike the other. That way, they would swim away from the dog they disliked and swim towards the dog they liked to the end of a pipe.

Decoy dogs were trained to jump out of screens and run up pipes. Ideally, their handler would be behind a specific screen, and upon command, the dog would run up whichever pipe it was asked to do so. The decoy ducks would follow it up a pipe, then the dog would return to the screen through the dog-jump and the decoyman would trap the ducks who were now deep into the pipe.

Sometimes, though, wild ducks got “stale.” This happened when the same wild ducks had been living in the same decoy for so long, they were now accustomed to seeing the dog and the decoymen and would no longer enter the pipes. The freshest ducks came straight from the coast, and decoymen could tell which ducks were fresh because of the waterline left on their feathers from the saltwater. Sir Payne-Gallway writes about how one time, one of his lady friends brought her pug to his decoy screen. Because his ducks were stale, he used her pug to push them into the pipe. “The wild ducks tore after him up the pipe at once, and a good catch was the result,” he wrote. “Whether it was the curl of the pug’s tail, or a very large black spot near it, or his quaint, well-fed appearance, can be only conjecture.” He also mentions that a painting of a rare Newfoundland used as a decoy dog can be viewed at Fritton Hall.

Dogs weren’t the only animal that Sir Payne-Gallway used to trap ducks. “I have tried a cat, a ferret, and a rabbit. They all attract, but are next to impossible to manage,” he wrote. He also mentions that one time, he “bribed an organ-grinder to lend me his monkey.” He then tried to use the monkey to push ducks into the decoy pipes, but unsurprisingly, the ducks were terrified by it. Each time he brought out the monkey, the wild ducks would flush and fly away for an entire day. “Finally, the monkey tumbled into the Decoy, and nearly died from fright and cold, and I narrowly escaped having to replace him.” Hopefully, he returned the monkey to the organ-grinder after this incident.

Duck Decoys in North America

“There are two things known to have originated in America: quilts and duck decoys,” said Rob Sawyer, a Texas waterfowling historian, author, and duck hunting guide. “There are photographs of duck netting structures built in Texas before live decoys were outlawed in 1935,” Sawyer continued, mentioning that Americans started carving wooden duck decoys in the early 1800s, and “Britain followed suite.”

Fake ducks originated in North America. Prior to European settlers carving their own wooden decoys, Native Americans built them out of natural materials or stuffed waterfowl skins and used them to kill wild birds. However, I am certain they didn’t call them “decoys.”

“The only specimens of Native American origin that I know of come from the Lovelock Cave Expedition in Nevada, though the Native American origin of decoys as fake ducks does not seem to be a hotly contested topic,” said Heasley. Although I can’t find much on Indigenous names for fake ducks made of natural materials, European settlers apparently continued to call them “decoys” instead of adopting an Indigenous word for the item.

So, how did the word “decoy” cross the Atlantic Ocean, earning a new definition along the way? No one really knows. It’s also curious that Sir Payne-Gallway uses the word “maize” in his book from 1886. Maybe we unintentionally traded the term “maize” for “decoy,” but I digress. Perhaps the phrase “decoy ducks” originated from those tame ducks planted inside each duck trap in Europe, and when live trapping was outlawed and waterfowlers fully switched to fake ducks, the phrase stuck. Without pipes and overhead netting, a decoy duck is still a decoy, whether it’s a live duck or a fake duck. Either way, finding documentation of the first uses of the word “decoy” on this continent would be enlightening for many North American waterfowling history enthusiasts.

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was born in Maryland and raised in southern Wisconsin, where she also studied wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2018, she moved to Gunnison, Colorado to earn her master's in public land management from Western Colorado University. Gabby still lives there today and shares 11 acres with eight dogs, five horses, and three cats. She herds cows for a local rancher on the side.