Home » Firearms and Shooting » Shotguns » How the Boxlock Shotgun Became a Standard

How the Boxlock Shotgun Became a Standard

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's…

A look at the history behind the boxlock shotgun and the insult that conquered the world

For every first place there is a second, and for every top dog there are others snapping at its tail. In the nineteenth century, London was the capital of first-rate gunmaking. Birmingham, 100 miles north, was the runner-up, and the major gunmakers there—W. & C. Scott, W.W. Greener, Westley Richards—were doing all they could to develop new guns that would put them on top. Today, you and I owe a huge debt to this struggle and to the shotguns it created.

From the 1830s through the end of the 19th century, sporting guns followed the rest of the world into the modern age. Out went muzzle-loaders using flints or percussion caps to ignite black powder and fire loose shot, in came breech-loaders using firing pins to strike primers and fire self-contained shells. Even though these breech-loaders were game-changers, almost all of them inherited a handicap from the past: Exposed hammers. So, while a breechloader was simpler to load, shooting it wasn’t; you still had to draw back and cock the hammers one at a time before firing.

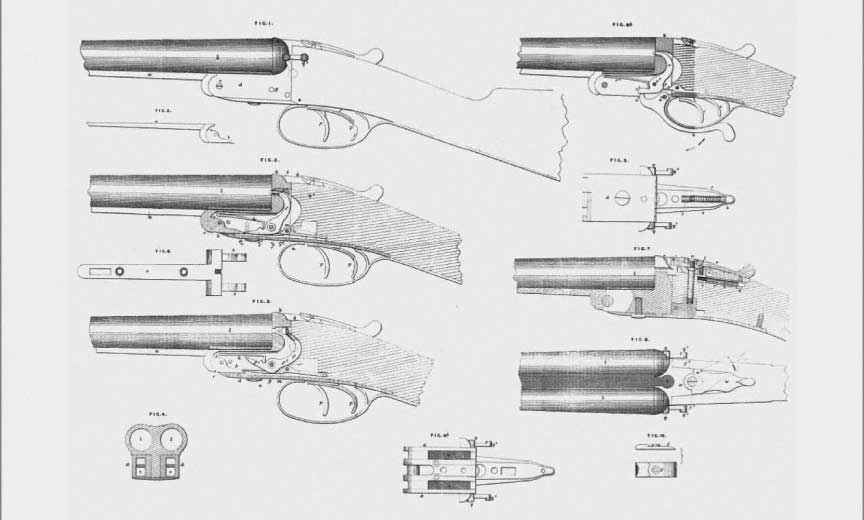

The first practical solutions to this problem showed up around 1870. Called “hammerless” guns, they moved the hammers out of sight and out of reach. They cocked on their own, usually when you loaded the gun. Three of the most important hammerless shotgun designs were patented by Joseph Needham in 1874, by William Anson and John Deeley for Westley Richards & Co. in 1875, and by the Rogers brothers in 1881. While these patents introduced similar ideas, these ideas pointed to different directions for the British gunmaking trade. They also started a brawl that’s still being fought today.

Sidelocks and boxlocks are the English and German Shorthair Pointers of the gun world. If you’re a devout fan of one, you’re certain the other’s no good, but like the breeds, both types of shotguns have their merits. Needham and the Rogers brothers created some of the first successful hammerless sidelocks. These shotguns earned that name for an obvious reason: their locks, which contain the hammers and parts like the mainspring and sears, are mounted on either side of the action (where the barrels hook into place and join the rest of the gun). Hammerless sidelocks are basically hammerguns minus the exposed hammers and plus a cocking mechanism. (BTW: most antique muzzleloaders are sidelocks, and so are most shotguns with exposed hammers, AKA hammerguns.)

The boxlock, which Anson and Deeley created, is far more innovative. It still has hammers, but they’re tucked away inside the action along with the mainspring and sear. Boxlocks also have fewer parts than sidelocks and they’re stronger in many ways. But as good as boxlocks are, they have a fault, at least in the eyes of some people: they can be tall and it can be cumbersome looking through their actions into the stocks. This keeps them from having the sleek, snaky-looking of a sidelock. Trivial? Yes—but a big deal to some people. In fact, the word “boxlock” was an insult aimed at making these guns seem crude and several steps down from the top sidelocks sold in London by the major makers. While this insult was far from fair, it was effective.

So why didn’t the boxlock take over the British shooting world? One word: snobbery.

If you’ve ever fired a side-by-side or over-under, there’s a 99.9% chance your hands have touched one of Westley Richards’s patents. Westley Richards & Co. opened for business in 1812, and in the 19th century, they invented the top-lever, the rib extension, the dolls head, and, as noted, the boxlock shotgun. Called the “Anson & Deeley Hammerless Gun” when it was introduced, the gun was a revelation—and a revolution. It had all the hammerless-shotgun benefits already mentioned plus it was easy to open, cock, load, and fire. A famous Victorian shooter wrote “… I most highly and thoroughly approve of this gun, and most strongly recommend it to my brother sportsmen.” So why didn’t the boxlock take over the British shooting world? One word: snobbery.

“Best” is an uncompromising word, and the term “Best Gun” is meant to exclude as much as it’s meant to explain. Great Britain was stratified into rigid classes in the 19th- and early 20th-century: Royals, Aristocrats, Knights, the Gentry, and on down to people like you and me. The people at the top set the styles for everyone else. These elites bought beautifully made, top-grade guns from London makers like James Purdey & Sons, Holland & Holland, and Boss & Co, and these guns came to be known as Best Guns. They were always sidelocks and they were always from London makers. The people who emulated these elites adopted the same attitudes and snubbed guns and gunmakers from the rest of the UK. Regardless of how nice a boxlock shotgun was, and Birmingham firms like Westley Richards, W.W. Greener, and G.E. Lewis built top-quality boxlocks, the people at the top rarely considered them—unless it was for a child learning to shoot or a gamekeeper working on their estate.

Fortunately, Birmingham makers found demand for their guns elsewhere. Side-by-sides by W.& C. Scott and W.W. Greener sold well in Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. On the west coast, a British gunmaker named J.P. Clabrough opened a shop in San Francisco that sold shotguns, rifles, and pistols made in Birmingham (San Francisco was a mean town then—a powerful, easy-to-conceal revolver called the “Bull Dog” was popular). Westley Richards licensed the American gunmaker Harrington & Richardson to build Anson-and-Deeley-patent boxlocks at a factory outside of Boston. These shotguns were some of the finest side-by-sides made in this country.

America flourished in the 19th century and more people had money to buy nice shotguns—or shotguns of any kind. The entrepreneur Charles Parker noticed and his company developed a boxlock of its own. So did Remington Arms, Colt, and the Ithaca Gun Company. In the 1890s, the Belgian gunmaker Francotte started exporting their version of the Anson & Deely Hammerless Gun to America. So did H.A. Lindner, a German working with a New York City businessman named Charles Daly. In the 20th-century, the boxlock’s popularity in the U.S. soared. Ithaca sold more than 223,000 of its Flues-model from 1908-1926. Ansley H. Fox introduced his version of the gun in 1906, and in 1930, Winchester introduced the Model 21, their take on the design.

Back in the UK, the sidelock was still king–and still the type of shotgun shot by the King and other folks at the top of society. But makers throughout England and Scotland were selling many more Anson & Deeley-patent shotguns to everyone else. On the continent, Italy’s Beretta and the German makers Merkel and Sauer were building Anson & Deeley boxlocks. After World War II, the Japanese gunmaker Miroku did the same. From 1971 to 1983, they even built a model for Browning called the BSS. Boxlocks are still being built today. The Spanish company AYA makes them and so does the Italian company Piotti. Here in the United States, the Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company’s RBL is an Anson & Deeley-style boxlock and so is the Savage Fox A Grade. Of course, Westley Richards, the creator of the very first boxlock, is still in business, and 145 years after filing the patent for their Anson & Deeley Hammerless Action, they’re still building these guns in both shotgun and double rifles. Some people even think the Westley Richards guns of today are better than the traditional “Best Guns” still being built in London. They may be right.

Gregg Elliott is the Shotgun Editor for Project Upland. He's been interested in shotguns and gundogs since he was a kid. Today, he blogs about both at www.DogsandDoubles.com and posts to Instagram @dogsanddoubles

Why is there a drop lock action featured on an article about box locks?

Because the droplock is a boxlock. Instead of mounting the lockwork on the action, WR mounted it on plates that drop out of the action. But the setup is the same, action is pretty much the same — maybe a bit wider to make room for the plates.

Gregg

I see you changed the main photo and added additional clarification under the other.

It was just odd to see a drop lock prominently displayed on an article that didn’t even mention drop locks at all. Sure they are similar in their primary design, but one is definitely different than the other. Out of all the awesome regular box locks out there, I just thought it was weird to showcase a drop lock like that.

Box lock gets the job done. Stronger less complicated. Side lock can be a work of art. If you take apart a side lock the fit and finish can be amazing. Dave Sinnerton is a gunsmith in the UK. He worked at Purdey for many years as a finisher and now produces his own guns. If you can find one and take it apart, it is not the same. That being said, when you pull the trigger, out in the field, and your dog and you do your part, the bird will not know the difference.

1) The boxlock was invented before the hammerless sidelock (Holland or Beesley patents).

2) The King did not like hammerless sidelocks, he compared the to a rabbit without ears.

3) exposed hammers are not a disadvantage and some have automatic cocking.

4) please detail the Needham and Rogers patent?

Sort of right, but by no means all correct and far from the true story.

This article is just “reverse” snobbery. We are blessed that we can shoot what we like. Actions that stand the test of time, both “side” and “box”, are good enough for anyone.