The West Siberian Laika to the East Siberian Laika History, Breed Information, and More

The complete breakdown of the versatile Laika dog breeds

Boreal forests of Europe are not very fertile places and, until recently, people who settled there found it hard to support themselves with either hunting-gathering or agriculture alone. They learned to combine the two, plowing in the summer and hunting in the winter. Hunting yielded not only meat but furs as well, which became more and more important as civilization progressed. Sable pelts fueled the expansion of Moscow’s reach to the East, engaging one indigenous people after another in fur trade and hunting. Everywhere from the Okhotsk Sea coast to the fjords of Scandinavia, hunters found an invaluable assistant in a medium-sized dog with pointed ears and a bushy curled tail that helped them harvest anything from grouse to bear to moose to marten: the Laika.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 Issue of Hunting Dog Confidential.

Hunting with a Laika

The word “laika” stems from the Russian verb “лаять” (, to bark). This doesn’t mean the dog is supposed to yap and woof all the time. In fact, the Laika must keep silent as it searches for game, even as it follows a hot trail. Only when the quarry is secured in one place—such as chased up a tree—does a Laika give voice.

Your first hunt with a Laika is almost sure to leave you bewildered. Unleashed, the dog simply vanishes in the woods. You walk along in your chosen direction, wondering whether the dog became lost, or perhaps called it a day and ran home. Fear not, for the Laika is there and knows exactly where you are. Sometimes you may even see its face make a brief appearance in the bushes as if to say, “You there? Good,” before it disappears again.

Eventually you will hear a cautious bark. If you’ve been hunting a lot with this particular dog, you already know what it has at bay from the nuances of how it gives voice, but there’s always room for the unexpected. It could be a squirrel the dog found in a tree or chased there from the ground, or the Laika might have flushed a covey of black grouse and followed one of the birds to its perch. Either way, the Laika sits under the tree and barks carefully while the forest critter tries to figure out what this weird kind of fox or wolf is doing. Meanwhile, your job is to stalk the location of the bark and make out the quarry (hint: a Laika’s muzzle ought to be pointed at it).

Squirrels and grouse are typical game animals for Laikas. Other types of game require different approaches. Bears, for example, are pursued with a team of two or three Laikas who keep the bear at bay by taking turns charging and dodging it. As the bear charges one of the dogs, another dog sneaks behind to deliver a solid bite in the tender area between the bruin’s hind legs. Naturally, as the bear turns around to attack the impudent creature behind it, the other Laika will go for the bear’s newly exposed rear end. For this kind of hunting, the Laika requires a combination of courage, intelligence, and agility; any dog that doesn’t have all three is either useless or short-lived.

With the moose, the bite-dodge-bark routine is both counterproductive and risky. The long legs of a moose are deadlier than a bear’s claws and, if the bull starts putting one of them in front of another, it won’t stop until it is far out of the hunter’s reach. A Laika’s work on moose is like a showdown straight out of a spaghetti western movie; it’s a delicate balancing act designed to create uncertainty in the moose’s mind. Ideally the moose will stay put, occupied with figuring out if the obnoxious, barking animal should be stomped on or avoided, until the hunter arrives to take the shot.

But the absolute pinnacle of Laika performance is hunting marten and sable. The trail left through the woods by these animals is long, winding, and complex. They travel quickly across the ground, then climb a tree and hop from branch to branch in search of squirrels and birds, then run along a fallen log. Right and left, back and forth… wherever their nostrils catch the scent of food. The Laika’s job is to follow this baffling track using evidence as scant as a bit of bark fallen from the treetops. At bay, marten and sable—both members of the mustelid family—are not as naïve as squirrels and are much more likely to seek an escape. In this case the Laika’s job is not just to bark, but also to prevent such an escape.

Laika breeds

Laikas are the product of severe and merciless selection. Traditional lore said that at the start of the hunting and trapping seasons, a hunter would take a number of young dogs out to the taiga, where each one would have a chance to prove themselves. Any that were not up to the task were culled. Many sources claim that in the summer, dogs were deliberately not fed; they were supposed to provide for themselves by catching mice or anything else they could eat. The result of this cruel selection, according to contemporary accounts, was that in the old days one could come to a hunting village, pick any random dog, and it would hunt as well as any other.

Since there were no other breeds of dogs around at the time and all dogs were of roughly equal quality, nobody really paid much attention to how their Laikas were bred. Predictably, many populations of native Laikas were lost or diluted when other breeds of dogs were brought in by newcomers during the exploration of Siberia and the Russian north in the 1800s. Fortunately, by the 1880s, Laikas attracted the attention of sport hunters and dog breeding enthusiasts in Russia’s big cities, who established regulated breeding programs. Because of the importance of the fur export in the USSR, a number of state-run Laika kennels were founded.

Though early descriptions by Prince Shirinsky-Shikhmatov and Maria Dmitrieva-Sulima focused on the differences between dogs kept in various localities by different ethnic groups, all Laikas were entered in dog shows and stud books indiscriminately. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that the first regional variety of Laika, the Karelo-Finnish Laika, was recognized as an independent breed. Modern Russian studbooks follow the classification suggested in 1947 by Eduard Shereshevsky and recognize four domestic breeds of Laika: the Karel Laika, the Russian European Laika, the West Siberian Laika, and the East Siberian Laika.

Regardless of the breed, the Laika is a medium-sized dog with sharp, erect ears and a curled, bushy tail, the tip of which should touch the spine or, better yet, make a full curl. The head is wedge-shaped with a wide, flat forehead and a short, pointed muzzle. The Laika has a strong, square body. The hair is medium length with a strong, hard overcoat and a thick undercoat; color varies with the breed, but is never spotted or coffee-colored.

Karel Laika (Rus: Karelskaya Laika)

The Karel Laika (Rus: Karelskaya Laika) was known until 2010 as the Karelo-Finnish Laika (Rus: Karelo-Finskaya Laika). Many experts—especially from Finland—believe it’s the same breed as the Finnish Spitz, and the two breeds used to be cross-bred. Since 2010, however, the Russian Cynological Council no longer recognizes such crosses and even dropped the word “Finnish” from the breed name. The Karel Laika is the smallest Laika breed (42-50 cm males, 38-46 cm females). Its most defining feature is its foxy red color. This is also listed as the breed’s biggest disadvantage, as bad hunters may misidentify them as foxes during the excitement of the hunt. Light and agile, the Karel Laika is described as a perfect “small game” dog.

Russian European Laika (Rus: Russko-Evropeiskaya Laika)

The Russian European Laika (Rus: Russko-Evropeiskaya Laika) is bigger than the Karel Laika (52-58 cm males, 48-54 cm females). The breed standard was based on dogs kept in the Komi, Perm, and Arkhangelsk regions; it’s possible that the Russian European Laika could be related to the Finnish Bear Dog. Its characteristic coloring is black and white. Bigger and somewhat more aggressive than the Karel Laika, it shines equally on big game and small forest game hunting.

West Siberian Laika (Rus: Zapadno-Sibirskaya Laika)

The West Siberian Laika (Rus: Zapadno-Sibirskaya Laika) originates from dogs kept by the Khanty, the Mansi, and other peoples of the West-Siberian Plain. It is bigger than the Russian European Laika (55-62 cm males, 51-58 cm females) and the body is a bit longer. The color can be white, grey, fallow, or—more typically—a combination of the colors. Waterfowl hunting being an important part of the Khanty and Mansi traditional lifestyle, the West Siberian Laika usually takes to water and retrieves with more willingness than other Laikas. This makes it, in the opinion of many hunters, the most versatile Laika of all.

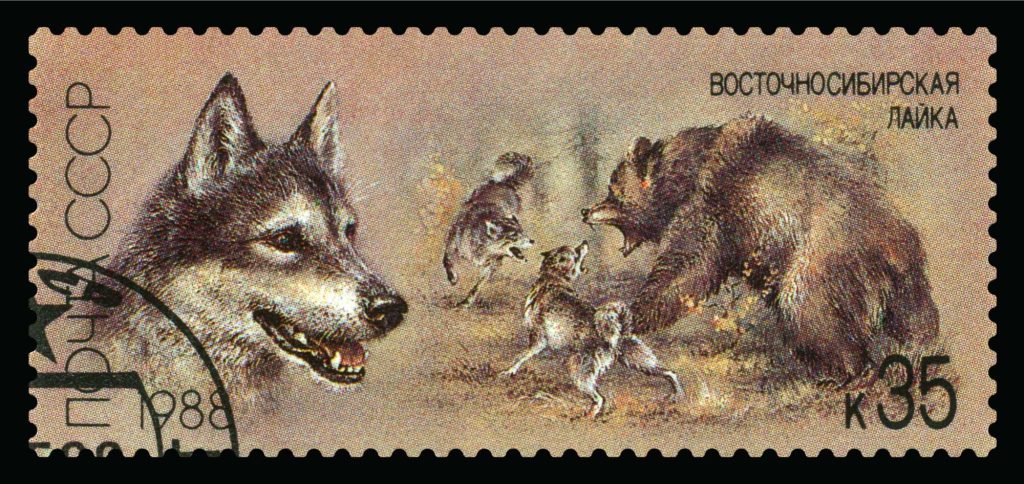

East Siberian Laika

The East Siberian Laika comes from the highlands east of the Baikal that continue up to the Pacific Coast. Many indigenous people of the area used them as double-duty sleigh and hunting dogs. Consequently, the East Siberian Laika is the largest breed of the Laika (55-64 cm males, 51-60 cm females), and its body is longer in proportion to its height. Its color may be black, fallow, or grey. It is usually darker at the spine and sides with a light underbelly and legs, in wolf-like fashion. This is the only breed of the Laikas that is allowed to have a tail that doesn’t curl all the way to the spine.

Temperament and behavior

A Laika is pure independence with four paws and a tail. It has very little of the perpetual adolescence that usually differentiates domestic dogs from wild canines. This is not to say that it is incapable of teamwork; a Laika will form a very efficient team with other dogs and humans. But a typical Laika afield acts as if it is the star of the show and the human is simply there for grunt work and heavy lifting. Whatever gene is responsible for robot-like obedience in some dogs is missing from the Laika DNA; it will do what intelligence, experience, and instinct dictate as the best course of action. If that happens to be what you order, great; if not, too bad.

The bright side of the independence is that, coupled with armor-piercing enthusiasm and willingness to hunt, good Laikas live and breathe hunting. The extreme independence makes the Laika a very difficult animal to keep as a companion dog. Non-hunters with a taste for Laika-like looks generally prefer the Husky or the Spitz, leaving the Laika primarily in hunters’ hands.

The question of versatility

One dog to hunt them all, one dog to find them, one dog to bay, retrieve, and—when they’re crippled—stop them? Not so fast. As a breed, the Laika can hunt everything you might find in the Eurasian boreal forest. On top of that, Laikas can be taught to work as a flusher, retriever, and even a scent hound. But that doesn’t mean each individual dog is capable of doing it all with equal success; the perfect all-around Laika, like the Ring of Power, is more of a legend than a reality.

Some dogs have a natural inclination to pursue certain kinds of game, while others may lack the sophistication required for moose or sable hunts, or don’t have the right balance of courage and caution for bear. The hunter’s tastes play a big part, too: a Laika will learn to prefer the kind of game that evokes the strongest emotional response in its human. In fact, many hunters actually prefer specialized dogs that hunt just one quarry, so that they won’t have to deal with a dog “barking a squirrel” on a bear hunt or going on a wild moose chase when there’s a fresh marten track to follow. Many kennels advertise their pups as coming from “a line of big-game dogs,” or “sable dogs,” although this is often only a marketing claim.

Training and trials

The independence of the Laika leads some people to believe that you can simply unleash a pup in a forest and it will train itself. Nothing could be further from the truth. Training a young Laika requires not only many hours in the woods but also, as one trainer put it, “knowing how to be your own Laika.” In other words, you must also be able to track a marten as it hops from tree to tree. Starting a Laika out with the help of an experienced dog works, but carries the risk that the pup will be a perpetual co-pilot, unable to work independently.

Breeding of all hunting dogs in Russia is done on a points-based “bonitation” system, with points awarded for form evaluation, field ability, and the successes of the dog’s offspring. The problem with assessing the field ability of the Laika is that proper field trials can really only be organized in natural conditions with squirrels. Laikas can also participate in retrieve and blood tracking trials and ability tests, but none of this says anything about the potential to hunt big and dangerous game. Fenced wild boar or bear trials are no longer permitted, leaving a gap in determining which dogs come from good working lines. Perhaps the biggest challenge for Laika breeders and enthusiasts today is how to replace the old style big-game trials for the purposes of a thorough evaluation.

Laika today

The Laika is seldom kept as a companion animal in modern times. As a hunting dog, it has spread well beyond its original range. Independence and passion help the Laika adapt quickly to new prey species and environments, such as the pheasant in the Caucasus or the invasive raccoon and raccoon dog. Outside the former USSR, the Laika seems to have found a small but devoted following in Germany, where it arrived via Russian army units stationed in East Germany following World War II and apparently fits in the Gebrauchshund niche quite well.

In fact, the most common quarry for a Laika these days is a species that didn’t even exist where and when the Laika was formed: the wild boar. Many Laikas are kept by hunting preserves for big-game, for both dedicated hunting over Laikas and tracking animals wounded by the clients. Unlike the conventional European bloodhound style, where the dog works slowly and the hunter follows close behind, the Laikas will speed along the blood trail to catch up with the animal and put it at bay.

Fur harvest lost its national importance after the collapse of the USSR, but there are still about 40,000 people in Russia—mostly West and East Siberia—who make a living by hunting sable and other furbearers. Other people spend their vacations in the taiga, living the traditional way of the promyshlennik for two or three weeks, or enjoy a quiet hunt for nothing in particular—whatever the dogs can find—on their day off. For these people, a good Laika is as invaluable as it was centuries before.