Home » Hunting Dogs » Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever in History and Today

Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever in History and Today

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

A look into the unusual history of duck tolling and the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever

As far as the eye could reach, the middle of the stream and the broad water of the river below were covered with them. There were literally acres of ducks of all kinds, but “trading” was at an end, and shooting, except of an occasional single or stray duck, was temporarily suspended.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

“Well,” said B., ” I suppose now you’d like to see some duck-tolling?”

“I’d like to be told,” I replied, “what tolling is.”

Listen to more information on the Duck Tolling Retriever with Hunting Dog Confidential:

Duck Tolling and the Murray River Retriever

Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers with Grant St. Germain

What is duck tolling?

Nowadays, when we think of duck hunting, we imagine scenes of wing-shooting mallards in a marsh or stubble field. However, before the invention of firearms, ducks were not shot on the wing. They were caught with snares, shot with a bow and arrow or driven into nets. Eventually, techniques were even developed to lure ducks into cages.

So for centuries before the invention of the modern shotgun, the main goal of waterfowlers was to get as close as possible to sitting ducks. And even when the first shotguns did appear, they were too heavy and inaccurate to use for wingshooting, so hunters still had to somehow get close to sitting ducks so they could shoot them on the water. They had two choices: crawl, wade or paddle closer to where the ducks were or, somehow, lure the ducks closer to shore. One such luring method was ‘tolling,’ a technique that hunters learned long ago by watching wild foxes draw ducks closer to shore.

B. declined to answer my question and said the only way to find out was to see it for myself. We made for a sheltered cove and were shortly crawling on our hands and knees through the calamus and dry, yellow-tufted marsh grass, which made a good cover almost to the water’s edge. Joe left the dogs with us and, going back into the woods, presently returned with his hat full of chips from the stump of a tree that had been felled. The ducks were swimming slowly up before the wind and it seemed possible that a large body of them might pass within a few hundred yards of where we were.

The two dogs, Rollo and Jim, lay down close behind us. Joe, lying flat behind a thick tuft a few yards to our right and about fifteen feet from the water’s edge, had his hat full of chips and held the young spaniel beside him. All remained perfectly quiet, watching the ducks. After nearly three-quarters of an hour’s patient waiting, we saw a large body of ducks gradually drifting in toward our cove. They were between three and four hundred yards away when B. said: “Try them now, Joe! Now boys, be ready and don’t move a muscle until I say ‘fire!’”

Then Joe commenced tolling the ducks. He threw a chip into the water and let his dog go. The spaniel skipped eagerly in with unbounded manifestations of delight. I thought it for a moment a great piece of carelessness on Joe’s part. But in went another chip just at the shallow edge, and the spaniel entered into the fun with the greatest zest imaginable. Joe kept on throwing his chips, first to the right and then to the left, and the more he threw, the more gayly the dog played. For twenty minutes, I watched this mysterious and seemingly purposeless performance, but presently looking toward the ducks, I noticed that a few coots had left the main body and had headed toward the dog. Even at that distance, I could see that they were attracted by his actions. They were soon followed by other coots and after a minute or two, a few large ducks came out from the bed and joined them. Others followed these, and then there were successive defections of rapidly increasing numbers.

The more wildly he played, the more erratic grew the actions of the ducks. They deployed from right to left, retreated and advanced, whirled in companies, and crossed and recrossed one another. Stragglers hurried up from the rear, and bunches from the main bed came fluttering and pushing through to the front to see what was up in the water. Then, by the aid of their wings, sustained themselves a moment, and sitting down, swam rapidly around in involved circles, betraying the greatest excitement. And still the dog played, and played, and gamboled in graceful fashion after Joe’s chips.

By this time the ducks were not over two hundred yards away. Taking heart in their numbers, they were approaching rapidly, showing in all their actions the liveliest curiosity. It was an astonishing and most interesting spectacle to see them marshaling about, to see long lines stand up out of the water, to note their fatuous excitement and the fidelity with which the dog kept to his deceitful antics, never breaking the spell by a fatal bark or disturbing what was taking place all about.

By this time the nearest skirmishers were not a hundred yards off. As Joe threw the chips to right or left and the dog wheeled after them, so would the ducks immediately wheel from side to side. On they came until some were about thirty yards away. These held back, while the ungovernable curiosity of those behind made them push forward until the dog had a closely packed audience of over a thousand ducks gathered in front of him.

“Fire!” said B., and the spectacle ended in havoc and slaughter. We gave them the first barrel sitting, and as they rose, the second. We got thirty-nine canvas-backs and red-heads, and some half dozen coots.

The description above is from an article published in Scribner’s Monthly in November 1887. The author wrote that the dogs “. . . belonged to the breed known as Chesapeake duck-dogs . . . a short-haired water-spaniel, drawn from imported stock, and peculiarly adapted to the cold water, and has been cultivated for years and is greatly prized by the sportsmen of Maryland.” Further north in eastern Canada, another kind of dog had been cultivated for years and was greatly prized by the sportsmen of Nova Scotia, in particular by hunters in the area of Little River. Eventually, those dogs would come to be known as Nova Scotia duck tolling retrievers.

The history of the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever breed

Everyone seems to agree on the basic outline of the Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever’s origin story: Originally called Little River Duck Dogs, named after the region around Little River Harbour in Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia, tollers had been known in the region since at least the early 1800s. In 1945, the Canadian Kennel Club recognized the breed and renamed it the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. In the 1980s, the breed’s popularity soared after two Best in Show awards were earned by tollers and in 1995 the NSDTR was officially declared the provincial dog of Nova Scotia by an Act of the House of Assembly. Today, the breed is well established in Canada and the U.S. as well as parts of Europe.

Where there is some disagreement and a ton of speculation, however, is how the breed was developed and how the technique of tolling ducks was actually invented.

As for the breed’s origin, one surprisingly popular theory can easily be dismissed as an old wives tale since it involves foxes and dogs producing hybrid offspring, a genetic impossibility.

*Since foxes and dogs diverged over 7 million years ago, they are very different from one another and with different numbers of chromosomes and therefore cannot cross-breed. There have been a handful of reports over the years of dog-fox hybrids called “doxes,” but none have ever been substantiated.

Another theory is that native hunters in North America tolled ducks with dogs they had specifically bred to look like foxes. When the French and English began to establish settlements along the East Coast, they learned the technique from the natives, bred their flatcoat retrievers and spaniels to native dogs and ended up with the ancestors of today’s tollers. And while it is certain that indigenous peoples in North America did teach Europeans some of their fishing and hunting methods, and they did have excellent dogs which may have contributed to the genetic makeup of the NSDTR way back when, the most likely scenario for the development of the modern breed is that hunters along the eastern seaboard of North America crossed and then selected among dogs brought over by Europeans.

But what about the tolling technique the breed is known for? Who came up with the idea of using dogs that looked like foxes to lure ducks close enough to be shot by hunters hidden along the shoreline?

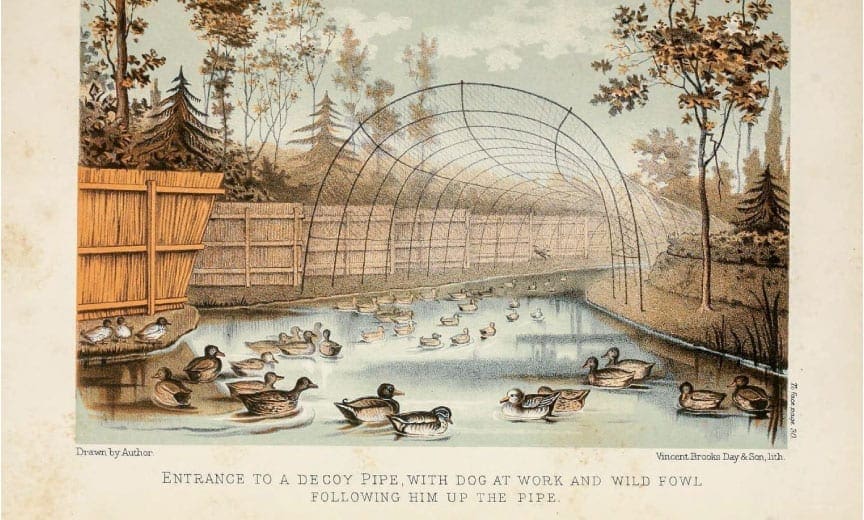

The most widely accepted answer is that the NSDTR’s tolling technique is a modified version of the art of luring ducks into specially made series of cages called ‘decoys.’ It is thought the practice first originated in Holland. The Dutch even developed a specific breed of dog, the Kooikerhondje, to lure the ducks.

By the 17th century it seems that the English had adopted the idea from the Dutch and there is some evidence that they too developed specific types of decoy-dogs or ‘piper-dogs’ to lure waterfowl up the ‘pipes’ of the decoy. Historian David Hancock speculates that English ‘piper dogs’ are the ancestors of the extinct Tweed water spaniel, the golden retriever and the Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever.

In the Book Of Duck Decoys published in 1866, author Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey provides a detailed description of ‘dogging’ in England where dogs that looked like foxes were used to draw ducks into a ‘pipe’ (tunnel) that lead to a cage. He then shares his thoughts on why ducks were prone to being drawn into the pipe by dogs.

Anything that appears strange or unusual in their eyes is a great attraction to a bird or animal, and in this consists their curiosity. I have seen tame Decoy ducks almost peck a fox curled up asleep, or seemingly so, on the bank of a Decoy (duck cage).

So with the wild ducks, if they see a dog hopping about near them, now close by, now lost to view, their curiosity and excitement cannot hold them. They must follow to know more about it, and so they do too, necks craned and eyes brightly inquisitive.

Their courage and curiosity last just as long as the dog retreats before them, as they think he does. They know nothing, of course, about the Decoyman hidden from their view behind the screens, who is really beckoning the dog up the side of the pipe and from the ducks.

Should the dog turn about and face them with a whine, or even look over his shoulder, off they all splash in a flutter, till he once more retires before them, when they follow him as before, and are thus gradually enticed on to their fate.

The natural instinct against a fox is very strong in all birds, but especially so in regard to ducks; for is he not always ready to pounce upon them unawares when enjoying a siesta, or even when sitting on their eggs?

Should a fox sneak along the banks of a Decoy, every duck is on the alert at once. They rush after him. I have seen them. They take good care, however, to keep at a safe distance; and as with a dog, should he turn towards them, they tumble over one another in anxious flight. I consider the ducks believe a dog to be in some sort a fox, or nearly related.

A fox-coloured dog, with a good brush (tail), is always a successful Decoy dog, if he otherwise does his work well. Ducks therefore follow dogs and foxes from curiosity, from hatred, as well as from braggadocio, and also because when he retires from them they imagine that for once in a way they are driving off a cruel oppressor—a natural enemy. They flatter themselves that their bold looks and assembled numbers bring about this satisfactory result.

A coloured cloth round the dog will sometimes move them when nothing else will. So will a fox’s skin strapped round him, with a trailing brush. But a dog will seldom work well with these additions. He feels he is made a show of.

Payne-Gallwey even tried other kinds of animals to lure the ducks into his decoy, with varying degrees of success.

I have tried a cat, a ferret, and a rabbit. They all attract, but are next to impossible to manage. I once bribed an organ-grinder to lend me his monkey. The fowl absolutely flew after him when first shown, but when he turned round and grinned at them they fled. When he sprang atop a screen and cracked the nuts I had tried to bribe him into acquiescence with, ending by scampering along the top of the pipe, every bird left the Decoy for the day. And no wonder.

Finally, the monkey tumbled into the Decoy, and nearly died from fright and cold, and I narrowly escaped having to replace him.

As good luck would have it, a lady friend to whom the Decoy was being shown, had brought her pug with her. The pug was started near the mouth of the pipe, whilst his mistress signalled to him from near the tunnel net. By mere chance the dog, untutored in the ways of Decoying, started gamely over a couple of jumps, and round a screen or two. The wild ducks tore after him up the pipe at once, and a good catch was the result. Whether it was the curl of the pug’s tail, or a very large black spot near it, or his quaint, well-fed appearance, can be only conjecture. At all events, the ducks evinced neither discretion nor hesitation on viewing him.

So it is certainly possible that the practice of tolling in North America was an adaptation of the Dutch-English decoy system. However, despite the similarities, there are some major differences. First of all, there is scant evidence that hunters on this side of the ocean ever built the elaborate decoy cages used in England and Holland. And they didn’t ‘toll’ ducks in order to trap or net them. North American hunters lured ducks closer to shore so that they could shoot them on the water or just as they were taking off. Finally, in North America, the dog didn’t just toll the ducks, he was also expected to retrieve them after they’d been shot.

The French connection to Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers

Among the earliest descriptions we have of tolling in North America was written by Nicholas Denys, a French explorer, colonizer and eventual leader of New France which at its peak extended from Newfoundland to the Canadian prairies and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1672, near the end of his life and after returning to France, Denys published a book titled The description and natural history of the coasts of North America (Acadia). In it, he mentions that foxes were known to lure waterfowl close enough to shore to catch them and that “. . . we train our dogs to do the same, and they also make the game come up. One places himself in ambush at some spot where the game cannot see him; when it is within good shot, it is fired upon, and four, five, and six of them, and sometimes more are killed.

Finally, he indicates that the same dog trained to lure the ducks was also expected to retrieve them.

At the same time the Dog leaps into the water, and is always sent farther out; it brings them back, and then is sent to fetch them all one after another.

Denys’ description perfectly reflects the tolling technique practiced along the eastern seaboard of Canada and the U.S. for centuries. Excerpts from his book have been used by several breed authorities to support the idea that this sort of tolling was a uniquely North American invention.

However, when I first read Denys’ account, one line stood out: “We train our Dogs to do the same . . .”

Who is the ‘we’ Denys refers to? And what were ‘our’ dogs? Was Denys referring to hunters in New France and the native dogs found there? If so, it would support the theory that the toll-to-shoot technique was a uniquely North American invention. However, in light of several documents I’ve recently come across in the archives of the National Library of France and elsewhere, a reasonable case could also be made that the tolling technique was actually invented in France and that the NSDTR’s ancestors were mainly French.

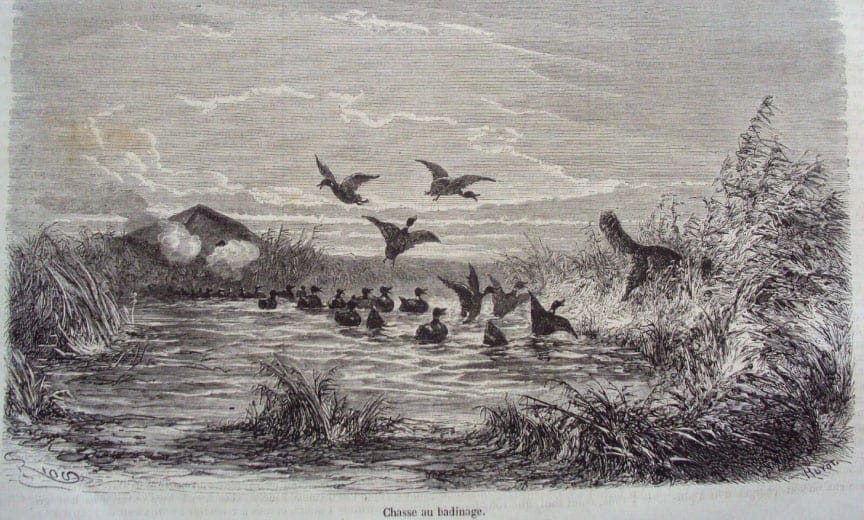

In an article published in France in 1837, the author, the Count of Reculot, explains the principles of “la chasse au badinage,” a type of hunting practiced in certain regions of France. What he describes is more or less identical to the hunting technique used by Tollers in Nova Scotia.

“. . . before daybreak the hunters will crouch down and remain hidden in their blinds, always downwind. There the greatest silence and the utmost immobility must be maintained. But that is the easiest part. There is one more thing to do, and that’s the most difficult: training the dog to play the role of a wild fox.

He then goes on to describe a type of dog that was bred to look like a fox and trained to imitate a fox’s behaviour on the shoreline.

About forty years ago, there was a breed of dog that folks around here called ‘Loulou.’ It had upright ears, a pointed muzzle, a red coat and a fluffy tail, basically all the qualities a hunter desired. Unfortunately, the breed is no longer found in the region of Franche-Comté and Burgundy, but it certainly exists in other parts of France, where perhaps it is still as popular as it used to be in our area.

Now the few hunters who hunt this way are reduced to using dogs of all kinds, as long as they resemble the shape and colour of a fox. And there are even some hunters who rub their dogs with yellow ochre to make it look like a fox; but it doesn’t really have the same effect. So, I always advise hunters to find, at any price, a young dog of the species described above. Get him while he is still very young and train him to fetch slain ducks from the water.

Additional support for the notion that the technique of tolling ducks within range of the gun was developed by the French is found in Henry Coleman Folkard’s book The Wild-fowler, A Treatise on Ancient and Modern Wild-fowling, Historical and Practical published in 1864.

The most attractive method of wild-fowl shooting in France is that in which a little dog is used for the purpose of enticing the birds within range of the sportsman’s gun; for this art the dog performs a similar part to that of an English decoy-piper, being taught to obey its master’s signs in silence, and to skip round reed-screens, erected for the purpose on the banks of lakes or other resorts of wild fowl.

The French sportsman, however, does not entice the birds up a decoy-pipe, and capture them alive; but, having allured them within range of his gun, he thrusts the latter through a loop-hole in the screen, and fires into the midst of the paddling, just as they turn tail to swim away.

Sometimes two or three gunners are stationed behind the same screens, and when the birds are numerous, they all fire at once. This practice is attended with far inferior success to that of the quieter operations of the English decoyer. After the discharge of a gun, every bird leaves the lake, and those which have once been enticed by the dog to approach the shore, are afterwards extremely wary and distrustful. The practice is only moderately successful in the best fowling districts throughout the whole country.

So if the practice of tolling ducks to within gun range and then shooting them on the water started in France, do Nova Scotia duck tolling retrievers trace their origins to the French “Loulou” or other French breeds? Maybe.

The toller’s color and head shape do have a certain resemblance to the Brittany, a French breed from western France. And there was a significant amount of trade between the French colony of Acadia and France, so it is very likely that dogs brought over from France did contribute to the toller’s genetic makeup. But dogs from other regions almost certainly contributed as well. The Cheasapeake Bay retriever is the other most likely candidate. When young, toller pups actually look remarkably similar to Cheasey pups. And Cheasapeake Bay retrievers were also used all along the eastern seaboard to toll ducks in the same way as NSDTRs were.

In any case, we will probably never know exactly how the NSDTR came about, but it is fun to speculate about it and to read fascinating accounts in the old literature of a hunting technique that has all but disappeared.

By the late 1700s, all the ingredients were in place in Nova Scotia for the development of a specialized breed of tolling dog. Spaniels and retrievers flourished along the eastern seaboard, trade and exchange were strong with France and England and hunters abounded in many regions. Add in a bit of luck, a ton of dedication on the part of dedicated hunters, and you end up with the modern Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever, a unique breed of gundog that makes an excellent companion in the home and a dynamic hunting partner in the marsh, field and shoreline.

Hunters looking for a toller to join them in the field are well advised to do their homework and look for a pup from proven working stock. Most tollers are bred by non-hunters as companion animals and family pets. However there are still some breeders that focus on the natural hunting abilities of their dogs and seek to place their pups in hunting homes.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

What a fun and informative article. I was not aware of the dogs nor the tactics for their use and your information was fascinating.

Is it possible to get a printed copy of this article for my Toller archives? I have been collecting printed articles about Tollers since I got my first one in 1976.

In addition, the article should be made available to the historical society in Little River. I always had sent them a copy of Quackers so they should have a place for this article.