Home » Hunting Dogs » Six Famous Hunting Dogs in History

Six Famous Hunting Dogs in History

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

The legacies of Old Drum, Fend L’Air, Judy the Pointer, and more reach far beyond the bird dog community.

To bird dog aficionados, names like Elhew Snakefoot, Count Noble, Shadowoaks Bo, and Manitoba Rap are well known. But to the average person, the names of dogs in our hall of fame mean absolutely nothing at all.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

But there are a few dogs from hunting breeds that have achieved fame beyond the bird dog world. Let’s have a look at some of the most celebrated among them.

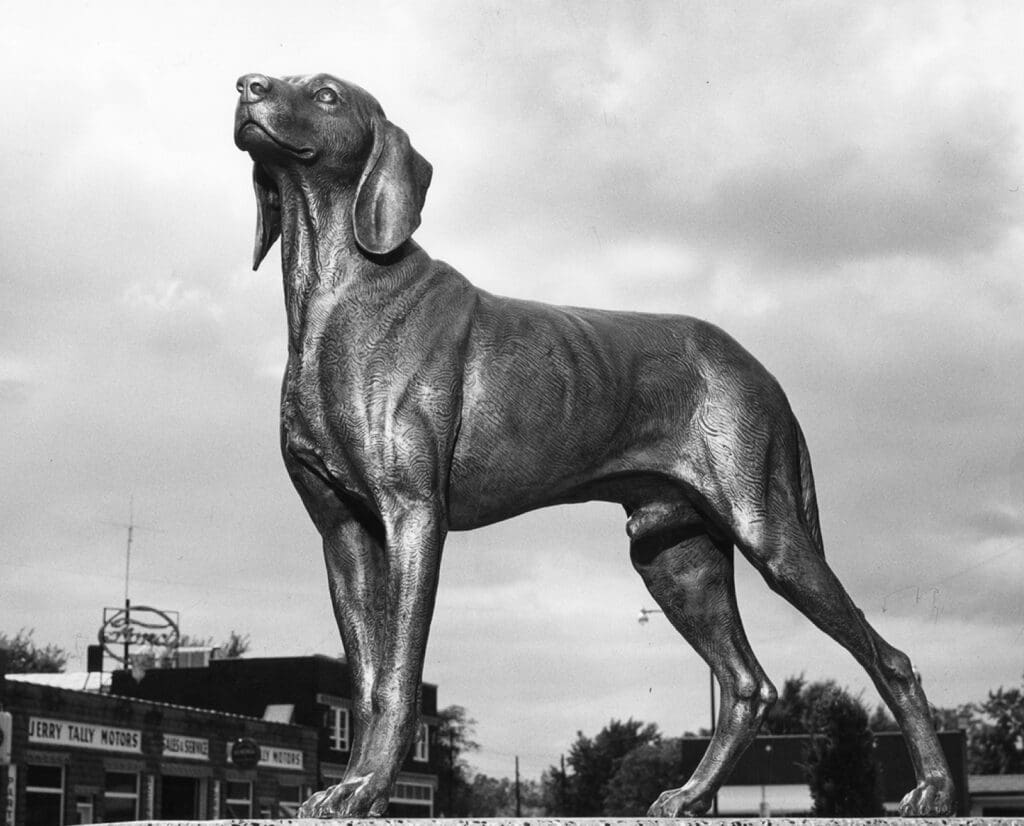

Old Drum the Foxhound

Old Drum was a foxhound owned by Charles Burden, a keen hunter who owned property along Big Creek in Johnson County, Missouri. On October 18, 1869, Burden found Old Drum dead from a gunshot wound. The killer was none other than Burden’s brother-in-law, Leonidas Hornsby, who lived nearby. After losing a number of sheep to predators, Hornsby had publicly vowed to kill any dog on his land and the first dog to cross the property line was Old Drum. Burden was furious and demanded justice.

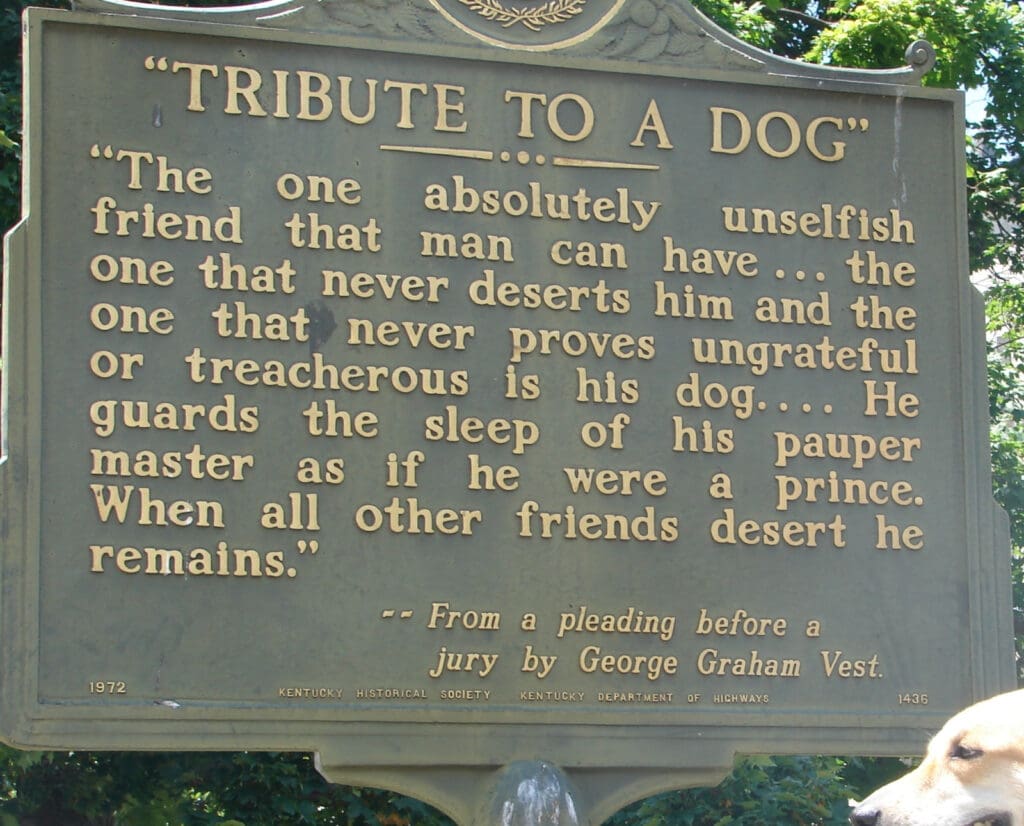

Within a year, a jury in Warrensburg, Missouri, awarded Burden 25 dollars (approximately $600 today). Hornsby appealed the decision, and the verdict was overturned. Undeterred, Old Drum’s owner petitioned for a new trial and hired new lawyers, including George Graham Vest, from nearby Boonville, Missouri. During this second trial, instead of going over the details of the case, vest focused on the relationship between Hornsby and his dog, and the relationship between mankind and all dogs. Reports from the time describe jurors openly weeping in court as Vest spoke. In the end, Old Drum’s owner was awarded a hefty sum of money for the loss of his dog. After the trial, the speech, to use a modern term, went viral. It was reprinted in newspapers across the US and internationally. Eventually, it became so famous that in 1958, the town of Warrensburg erected a statue to honor George G. Vest and Old Drum.

Vest’s speech, “The Eulegy of the Dog,” was recorded in the Congressional Record on April 23, 1990, 120 years after it was delivered:

Gentlemen of the jury— The best friend a man has in the world may turn against him and become his enemy. His son or daughter whom he has reared with loving care may prove ungrateful. Those who are nearest and dearest to us, those whom we trust with out happiness and our good name, may become traitors to their faith. The money that a man has he may lose. It flies from him perhaps when he needs it most. A man’s reputation may be sacrificed in a moment of ill-considered action. The people who are prone to fall on their knees to do us honor when success is with us may be the first to throw the stone of malice when failure settles its cloud upon our heads. The one absolutely unselfish friend that a man can have in this selfish world, the one that never deserts him, the one that never proves ungrateful or treacherous, is the dog.

Gentlemen of the jury, a man’s dog stands by him in prosperity and in poverty, in health and in sickness. He will sleep on the cold ground when the wintry winds blow and the snow drives fiercely, if only he can be near his master’s side. He will kiss the hand that has no food to offer, he will lick the wounds and sores that come in encounter with the roughness of the world. He guards the sleep of his pauper master as if he were a prince.

When all other friends desert, he remains. When riches take wings and reputation falls to pieces, he is as constant in his love as the sun in its journey through the heavens. If fortune drives the master forth an outcast into the world, friendless and homeless, the faithful dog asks no higher privilege than that of accompanying him, to guard him against danger, to fight against his enemies. And when the last scene of all comes, and death takes his master in its embrace and his body is laid in the cold ground, no matter if all other friends pursue their way, there by his graveside will the noble dog be found, his head between his paws and his eyes sad but open, in alert watchfulness, faithful and true, even unto death.

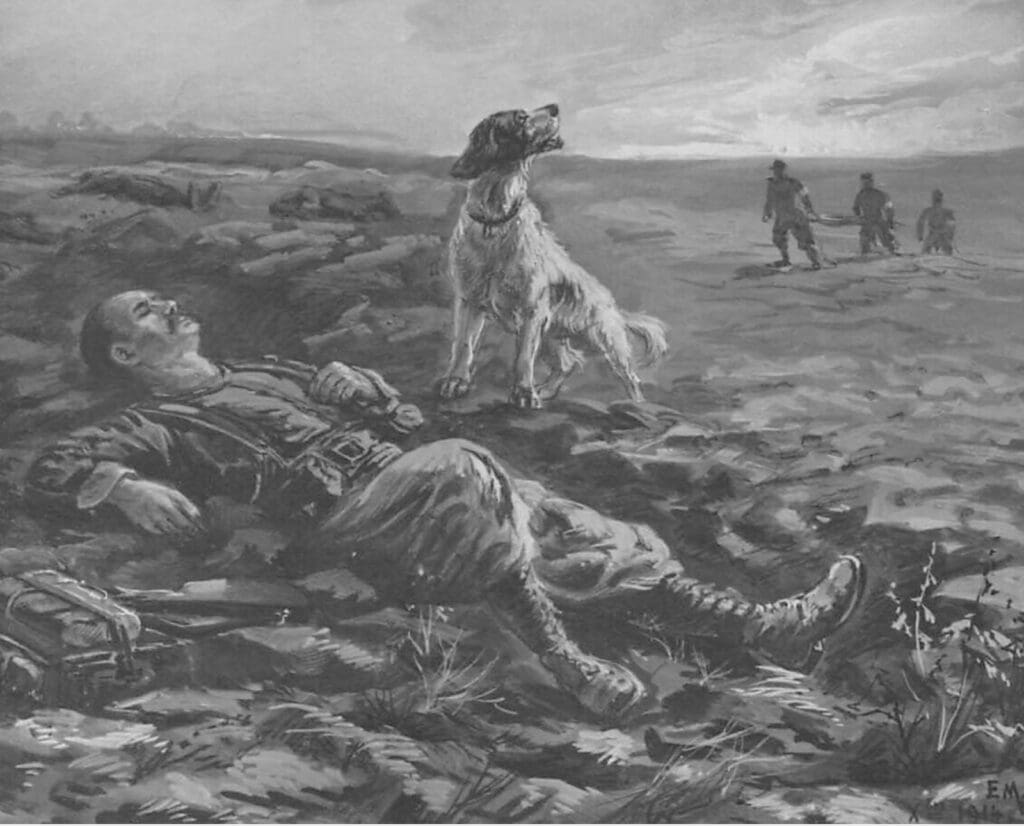

Fend L’Air the English Setter

Shells rained across the front line between the French and German armies in December of 1914. Twenty-eight-year-old Sergeant Ettienne Jacquemin crouched low in a trench near the town of Arras. Suddenly, a massive explosion erupted in the trench. The young Sergeant is trapped, buried beneath the rubble. His right leg is shattered, his right arm and hands pierced by fragments.

Only a miracle could save him. Just as he was about to give up hope, a dog appeared. His name was Fend L’Air (pronounced fawn’d lair), and he’d been with Sergent Jacquemin since they left Algeria to join his Zouave* regiment in France.

Originally owned by a well-to-do English hunter Jacquemin guided on quail hunts in Algeria, the young English Setter earned the name “Fend L’Air” because he ran so fast, he seemed to fendre l’air, or ‘split the air.’ When the war broke out, the Englishman had to return to his home country but couldn’t take his dog, so he gave him to Jacquemin. But it wasn’t long before Jacquemin had to leave Algeria to join the fighting.

Unwilling to leave his dog behind, he managed to smuggle him aboard the troop ship crossing the Mediterranean and keep him by his side all the way to the front lines. The pair remained inseparable even as they faced mortal danger at the battle of the Marne and on the front lines of the Pas-de-Calais. But on the 12th of December, 1914, their luck ran out.

The shell that burst next to Jacquemin killed most of his unit and buried him under a pile of clay. But Fend L’Air came to the rescue. He frantically dug through the clay so his master could breathe and then continued to dig until the soldier could free himself and wait for help to arrive.

Hours later, with Fend l’Air by his side, Jacquemin was evacuated to a nearby hospital at Aubervilliers. But when the Sergeant was transferred to a larger hospital near Paris, he was told that he could not take his dog with him. It was against the regulations. Left behind to fend for himself at the Aubervilliers train station, Fend L’Air stopped eating and drinking despite the best efforts of the men charged with caring for him. When a hospital administrator heard of the dog’s plight, he decided to ignore the rules and allowed Fend L’Air to visit Sergeant Jacquemin every morning at the hospital in Paris.

The story soon caught the attention of the local press and, eventually, the larger public. Fend l’Air’s photo was published on the front page of newspapers and artworks and postcards depicted his heroic acts. After the war, at a ceremony in Paris, Fend L’Air was awarded the “Collier d’Honneur” (collar of honor) for loyalty and bravery.

*The Zouaves (pronounced Zwav) are light infantry units of the French Army from North Africa. They were known for their brightly colored uniforms and reputation for being fierce fighters. They are among the most decorated units of the French Army.

Pluto the Pointer

Remember Mickey Mouse’s dog, Pluto? Did you know he was a hunting dog?

In one of the earliest Mickey Mouse episodes ever made, Mickey and Pluto go quail hunting. But Pluto had never hunted quail before, and he didn’t really know what to do. Mickey tried to teach him the ins and outs of being a bird dog by reading to him from a book. Mickey promised Pluto that if they were successful, they would dine on “quail on toast” and even a big juicy bear steak.

Hilarity ensued. As soon as they come across a bevy of quail, Pluto starts busting birds left and right. Mickey is furious and scolds him. The two then become separated, but this time, when Pluto finds some quail, he slams into a picture-perfect point and remains rock solid, even as Mickey screams for help after running into a sleeping bear. The bear chases them both, but they manage to escape back to camp, where they dine on a can of beans.

The film was nominated for an Academy Award after its release. Today, the entire episode is available on the internet.

Krambambuli the German Wirehaired Pointer

Arguably, the best-known story of a hunting dog in the Germanic world is Countess Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach’s tale of a dog named Krambambuli. Originally published in 1883, it was republished a year later in a collection of Ebner-Eschenbach’s short stories, Dorf—und Schloßgeschichten.

The story is well written, but it is a tough read since it has such a tragic ending. In a nutshell, it revolves around the relationships that a dog named Krambambuli forms with two very different masters. His first owner was a loving master, but when alcoholism ruined his career, he sold Krambambuli and turned to poaching. His second owner was an honest, hard-working ranger bound and determined to track down and punish poachers. Things come to a head when a gunfight breaks out between the ranger and the poacher, and Krambambuli has to choose between the two. Remembering his love for his first owner, he chooses the poacher’s side. But the righteous ranger fires and kills the poacher. He then scolds Krambambuli, calls him a deserter, and disowns him. The dog ends up roaming the countryside, almost starving to death. Meanwhile, the ranger changes his heart and decides to let the dog back into his home. But upon opening the door, he finds Krambambuli dead.

The story has been made into at least two films, both available online. The first, in black and white, was made in 1940. A modern, color version was made in 1998. In both films, Krambambuli is portrayed by a Deutsch Drahthaar.

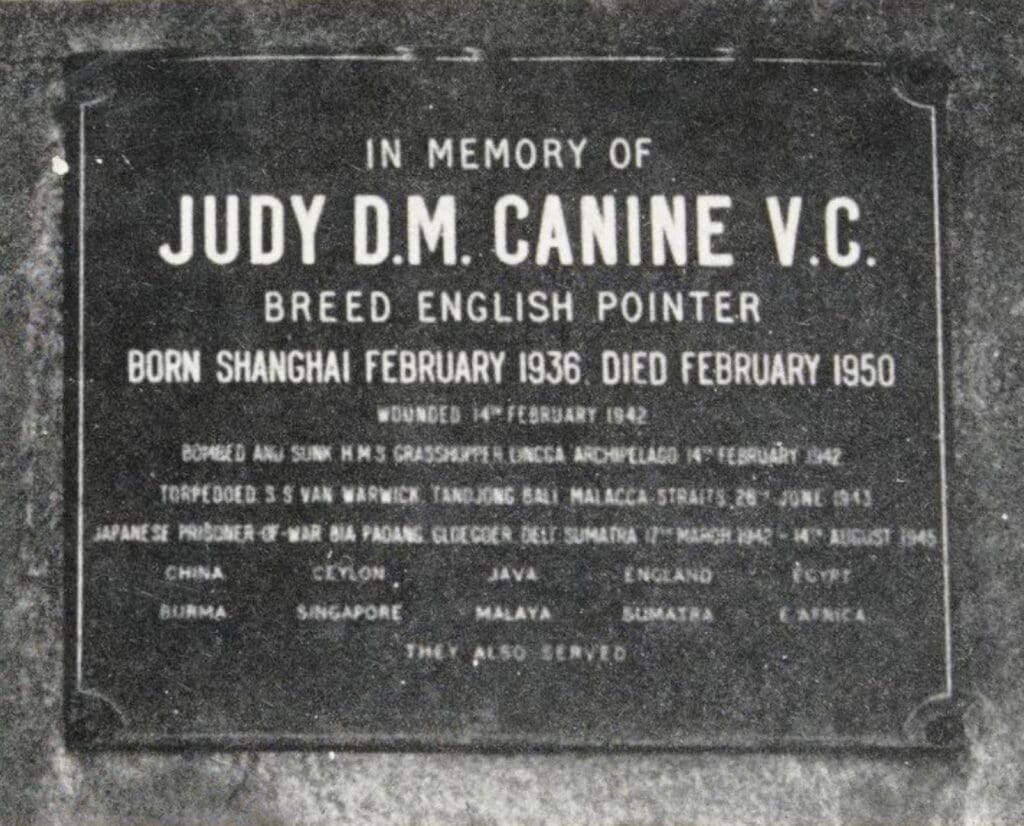

Judy the English Pointer

If you were to pitch the story of Judy the Pointer to a Hollywood studio, you’d probably be told that it was too outlandish. But the story is indeed true. Judy’s life as a ship’s mascot and then a prisoner of war is a roller coaster of emotion that has inspired several books and is now in development as a feature film.

Judy, a pure-bred liver and white Pointer born in 1936 at the Shanghai Dog Kennels, was first adopted by the crew of the British gunboat HMS Gnat as the ship’s mascot. The crew had hoped to use her as a gundog, but after the men began to treat her like a pet instead, one crew member wrote in his log book that “our chances of making her a trained gundog are very small.”

During the first year of the war, Judy and her crew faced bombs from the air and intense fire from enemy ships. They survived two shipwrecks and tried to escape encirclement by the enemy. Unfortunately, they were captured, the Judy and the crew spent years in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in North Sumatra.

Throughout it all, Judy remained loyal to the crew, helping them scavenge food and inspiring them to cling to life. Judy shared an especially strong bond with flight technician Frank Williams who would remain with her for the rest of her life. When the pair was eventually liberated from the camp in 1945, Judy was smuggled aboard a troopship back to England. When she was released from quarantine six months later, she and Williams were invited to London, where a ceremony was held a the Kennel Club. Chairman Arthur Croxton Smith awarded her a “For Valor” medal. A year later, she was awarded one of the highest awards for animals, the Dickin Medal, “for magnificent courage and endurance in Japanese prison camps, which helped to maintain morale among her fellow prisoners and also for saving many lives through her intelligence and watchfulness.”

She became the first and only canine member of the Returned British POW Association. Williams and Judy spent the post-war years visiting family members and friends of POWs who did not return, bringing them solace and comfort. They eventually moved to East Africa. Judy passed away in 1950 at nearly 14 years of age. She was buried in her RAF jacket with her campaign medal. Williams built a granite and marble memorial for her and included a plaque that told her life story.

Since her passing, her story has continued to grow in popularity. A book entitled The Judy Story: The Dog with Six Lives by Edwin Varley was published in 1973. In 2016, another book, No Better Friend by Robert Weintraub, came out. Yet another, Judy: A Dog In A Million by Damien Lewis, was published in 2017. A feature-length movie based on Damien Lewis’ book, Judy, More Than Man’s Best Friend, is said to be in development.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

Knowing as I do, that my hound would love any master to the same extent that he extends to me doesn’t dampen my fondness for him. The instinct displayed by these ones has shaken my hope in humanity. God, our Father knows all things , so I’ll remain and that with my hound to share my future. A whole lotta emotional investment in this love story.