Home » Hunting Dogs » Extinction: The History of Lost Dog Breeds

Extinction: The History of Lost Dog Breeds

- This article originally appeared in Volume 2, Issue 2 of Hunting Dog Confidential Magazine.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

Among pointing dogs, a number of breeds have already disappeared; others may follow them unless drastic action is taken

Saying I’m into dogs is like saying Manitoba winters are “a tad chilly.” I spend most of my waking hours hanging out with, thinking about, reading about, and writing about dogs. One of my favorite reads as of late is a blog connected to the Institute for Canine Biology website run by Carol Beuchat, Ph.D.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Dr. Beuchat’s post, “Celebrating the Preservation Breeders!” was a sort of good-news progress report on several breeding projects designed to save vulnerable breeds of dogs. Along with the report, the Institute for Canine Biology offers articles and even online courses to help breeders and breed clubs improve the odds of their breeds’ survival.

Reading those articles got me thinking about all the breeds of hunting dogs that are no longer with us today, and the reasons why they went the way of the Dodo bird.

Among pointing dogs, several breeds have already disappeared, and others may follow them unless drastic action is taken. France, for example, has already lost two breeds of griffon (the Boulet and the Guerlain), two breeds of braque (the Dupuy and the Mirrepoix), and one breed of épagneul (the Larzac). Germany lost the Württemberger and the United Kingdom lost the Llanidloes setter. Several spaniel, water dog, and retrieving breeds are no longer with us and entire types of hunting dogs like Alaunts are now gone.

So, what happened? Why did they disappear? Breeds can die and have died for a variety of reasons.

The founder(s) abandon it

Emmanuel Boulet spent massive piles of his own money and decades of his life developing his very own breed of griffon. For a while, he and his dogs were superstars in the show ring and in the field. The sporting press from the 1880s and ’90s is filled with articles on the Boulet Griffon, lauding the master breeder’s genius and casting him as the savior of the continental pointing breeds. The publicity soon attracted the attention of some of the most powerful people in the world, including Nicholas, the Tsarevich (Grand Duke) of Russia, who traveled to Elbeuf while on a state visit to France just to meet Mr. Boulet and see his griffons. Even the president of France paid homage to the great breeder, presenting him with a national medal of honor for his work. Legend has it that in return, Boulet offered the president a sweater knit from the wool of his griffons.

Yet despite the popularity of the Boulet Griffon and the fame and fortune of its founder, the breed faded into oblivion only a few short decades after Emmanuel Boulet’s death. It is tempting to conclude that it was the founder’s death that led to the breed’s demise, but the truth of the matter is that Boulet himself abandoned it in 1890. In a letter published in the sporting press, Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels tells us why.

It was also Mr. Boulet, who ranked as the top griffon breeder in France, who recently picked out three young dogs…in the Ipenwoud (Korthals’) Kennels. This gentleman stated to me that he now wanted to breed this line pure and not cross it with his line…because his dogs are too long- and soft-haired as a result of crossbreeding and he wants only prickly-haired dogs.

After Boulet’s death in 1897, a few breeders attempted to continue his work but were unable to prevent the Boulet Griffon from eventually disappearing just after the Second World War. For many years, the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) continued to publish its standard, but in 1984 the breed was finally removed from the list of recognized breeds and its standard dropped. Several years later, a Frenchman by the name of Philippe Seguela began a breeding program aimed at recreating the Boulet Griffon. He managed to produce dogs that were apparently quite close to the original in terms of looks and performance, but unfortunately, he abandoned the project in the early 1990s.

The founder(s) die and no one picks up where they left off

Aimé Guerlain was a rich man from the perfumer House of Guerlain. He invented the perfume Jicky, which is now the oldest perfume still available today. Aimé also invented his own breed of griffon and enjoyed some success in field trials and dog shows. Unfortunately, he was unable to gain many converts to the breed beyond the circle of his close friends. After Aimé’s death in 1910, it seems that no one stepped up to continue the project, leaving the breed to fade into the history books.

It fails to create a distinct identity

Throughout much of the 1800s, the Braque Dupuy was a relatively popular French pointing breed, but shortly after field trials and dog shows were established, it went into a steep decline. Eventually, the breed died out. It is hard to say exactly why it disappeared, but one major contributing factor was very likely what today we would call “poor branding.”

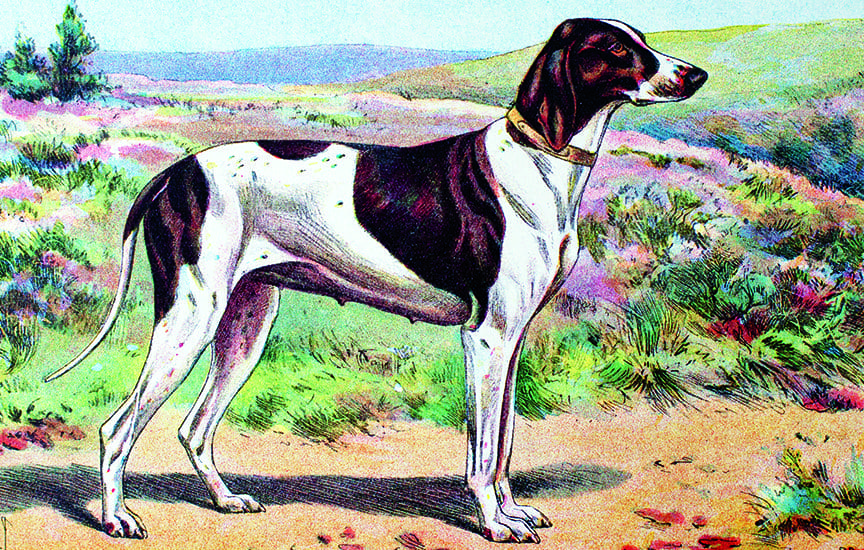

Unlike many other gundog breeds that were growing by leaps and bounds in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Braque Dupuy never managed to develop a distinct, recognizable identity. Some of its supporters thought it should be a should be fast, wide-ranging dog—basically the French version of England’s Pointer. Others thought it should be a slow, close-working trotter—a taller, thinner version of the old French Braque. Press reports from the late 1800s and early 1900s indicate that both types were around back then and each was promoted as the “true” Braque Dupuy.

Meanwhile, other breeds were growing quickly, thanks in part to clever, easy-to-remember slogans that their supporters used to market them. Brittanys, for example, were touted as dogs having “maximum qualities in a minimum of size” and Griffons were labeled “all-game, all-terrain” dogs. Dupuys, on the other hand, must have been a bit of a mystery to the average hunter looking for a four-legged companion.

It remains strictly confined to its native region

Breeds can sometimes thrive—at least for a while—in a particular region or country, but if they fail to generate any interest beyond their native soil, they can eventually die out.

In France, two breeds of pointing dogs—the Larzac Spaniel and the Braque Mirapoix—never made it out of southern France. Similarly, the Hertha Pointer remained confined to Denmark for nearly a century until it finally died out.

It falls victim to changes in hunting styles

In Wales, there used to be a breed of setters known as the Llanidloes setter, sometimes referred to as the Old Welsh Setter. Vero Shaw wrote that it was practically extinct by the late 1800s and that its “… loss is so greatly to be deplored that supreme efforts should be made to restore it, before all hopes of doing so are vain.”

Shaw also described the breed based on information he gathered from a Mr. William Lort, of Fron Goch Hall, Montgomeryshire.

“The colour is usually white, with occasionally a lemon-coloured’ patch or two about the head and ears. Many, however, are pure white, and it is unusual not to find several whelps in every litter possessed of one or two pearl eyes. Their heads are longer in proportion to their size, and not so refined-looking as those of the English Setter. Sterns are curly and clubbed, with no fringe on them, and the tail swells out in shape something like an otter’s.”

In a book entitled The Gun At Home And Abroad, published in 1912, an explanation for the disappearance of the Llanidloes is offered by Walter Baxendale, who also mentions two other strains of setters that died off for the same reasons.

were active little dogs, and well suited to the deep dingles and steep hillsides of their native Montgomeryshire. The late Mr W. Lort, a well-known shooting man, and born judge of every kind of animal, had a great opinion of their suitability for their work, and used to say, “‘You may beat us with your dogs on the flats and the tops, but we will beat you in the dingles and on the bottoms,” referring to his Welsh dogs and ground. This old breed is now practically extinct. The inroad of “driving,” and the introduction of more fashionable breeds, combined with want of care for them on the part of their owners, having brought about their downfall.

At Beaufort Castle, Inverness, there was at one time an old breed of setter kept up for many years in the family of Lord Lovat, and the pedigrees were jealously guarded. …Since the shooting on this estate has been let to American sportsmen, and “driving” has superseded the old method of shooting the moors over the setters, the kennel has gone down, and has by this time probably become extinct. A somewhat similar kennel of setters was kept at Cawdor Castle, Nairn. … The blight of “driving,” that has given the death-blow to so many fine old breeds, has, without doubt, extinguished this one also, as for many years no specimen of them has been heard of.”

It becomes genetically unsustainable

It is impossible to say just how many breeds and strains of hunting dogs have gone the way of the Dodo due to small populations and extremely high levels of inbreeding.

Once the dogs are painted into a genetic corner, they soon die out. Today, several breeds are facing this very problem. The Pont Audemer Spaniel, the Braque de l’Ariège, and the Stichelhaar are dangerously close to the point of no return.

It fails to gain official recognition from the canine establishment

The Württemberger, known in Germany as the Dreifarbige Württemberger or Dreifarbige Württembergische Vorstehhund, was a short-haired, tricolored pointing dog that disappeared just after World War I. Exactly where, when, and how it came to be is the subject of speculation. The most common assumption is that the breed was developed by hunters in the Württemberg region of southwest Germany in the 1870s. Some sources claim that Gypsies traveling from Russia brought the breed to the Württemberg region in the early 1800s, but others insist that it was an ancient breed, known in southern Germany for centuries.

Whatever their origin, heavy, tricolored pointing dogs were present in large enough numbers in the 1880s and ’90s to catch the attention of Germany’s Delegate Commission which, for a time, recognized them as a breed. But a separate stud book was never created for Württembergers and they, along with Weimaraners, were registered in the German Shorthaired Pointer’s stud book.

Apparently, a Dreifarbige Kurzhaar Klub (Tricolored Shorthair Club) was formed, but its efforts to gain official recognition for the breed failed. It is not clear exactly why, but it may have been because leading dog experts of the time believed that any tricolored coat had to be the result of crossbreeding to either Gordon Setters or some kind of hound, such as the Large Blue Gascony.

Physically, Württemburgers were fairly large dogs, up to 70 centimeters at the shoulder with a large head, heavy flews, and loose skin. They probably looked like a tricolored Bracco Italiano or Burgos Pointer. A fairly detailed description of the breed was written by J.B. Samat and appears in the book Les Chiens de Chasse, published by the Manufrance Company in the 1930s.

The Württemberger has not yet undergone the same transformation as the real German Shorthaired Pointer which, nowadays, looks nothing like its ancestors. The Württemberger is a fairly tall dog with a heavy appearance, but it is rare to see a well-built and absolutely correct example, for the hunters in Württemberg are not very fussy and have no particular interest in a carefully thought-out breeding system. However, there are two or three large kennels where the breed is carefully raised and where they have probably been improved in the same way as the other German breeds. The coat is tricolor marked with brown and tan spots and streaks on a blueish background, white with brown ticking with yellow markings above the eyes, on the cheeks, the edges of the ears, the lips, the chest, the inside of the legs and the underside of the tail.

In the book Deutschen Vorstehhunde, author Manfred Hözel states that the last litter of Württemberger pups was whelped near the city of Nanz, Germany, in 1910 and that two pups were exported to America. Other authors, however, have written that the breed managed to survive until just before the Second World War.

It never really existed

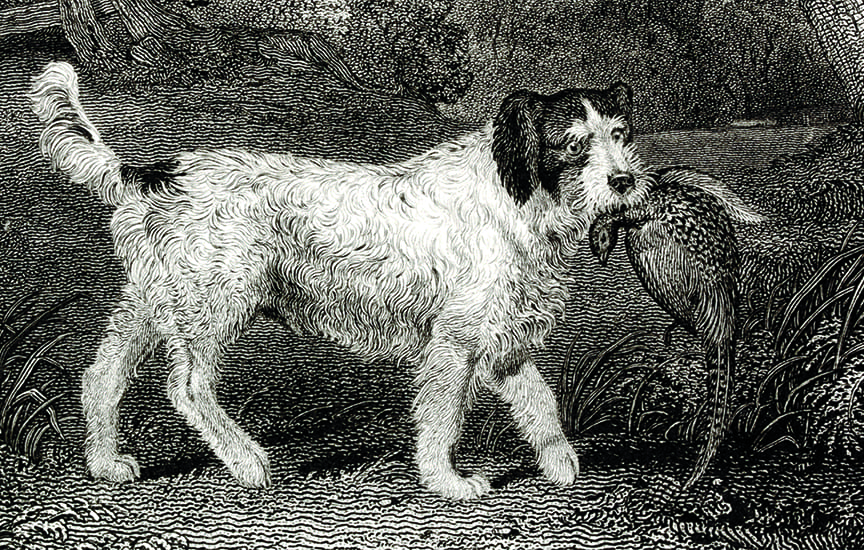

Russian Setters, rough-coated pointing dogs frequently mentioned in the sporting press of the 19th century, are no longer with us. But then again, they never were.

Reading through the old literature, it is clear that the terms “Russian Setter” and “Russian Pointer” were used to describe any rough-coated pointing dog in Britain at that time. Similar, if not identical, dogs were called Smousbaarden in the Netherlands, Griffons in France, and Polish or Hungarian Water Dogs in Germany. Before the late 1800s, none of them were “pure” or independent breeds. They just represented a type of dog that was found just about everywhere that sportsmen took to the field. A rough coat was their most distinctive feature and it was probably the reason that men in Britain called the dogs “Russian,” for it was commonly believed that people from the frozen eastern regions (and their dogs) were rather hairy and unkempt. In an article from The Farmer’s Magazine in 1836, we can see just how politically incorrect many of the writers were at the time.

“We may perhaps have seen a dozen of these brutes, which, like the people whence they derived their grossly misapplied appellation, are very uncouth, very rough, imperturbably stupid, and, by way of continuing the similarity to the greatest possible extent, will generally be found infected with loathsome vermin.”

Thomas Burgeland Johnson’s description of what he called the “Russian Pointer” in the 1819 issue of The Shooter’s Companion was equally negative.

Whether he be originally Russian is very doubtful; but he is evidently the ugliest strain of the water-spaniel species; and, like all dogs of this kind, is remarkable for penetrating thickets and bramble bushes, runs very awkwardly, his nose close to the ground (if not muzzle-pegged), and frequently springs his game. He may be taught to set, and so may a terrier, or any dog that will run and hunt, and even pigs, if we are to believe the story of Sir Henry Mildmay’s black sow; but to compare him with the animals which have formed the subjects of the two preceding chapters (setters and pointers), would be outrageous; nevertheless, I am not prepared to say, that out of a hundred of these animals, one tolerable could not be found; but I should think it madness to recommend the Russian Pointer to sportsmen, unless for the purpose of pursuing the coot or the water-hen.

References to Russian Setters in America are scarce, but there are a few; one, in particular, is quite well-known: the first Korthals Griffon to be registered with the AKC, a bitch imported from France, was listed as a “Russian Setter (Griffon).”

In The Complete Manual For Young Sportsmen, Henry William Herber (aka Frank Forester) wrote that Russian Setters were:

… rarely or never met with in this country. Could they be procured, I think of all sporting dogs they are the most adapted for ordinary American shooting, and the best of all for beginners. They have less style, and do not range so high as the English or Irish dogs, but that is no disadvantage for America, where there is so much covert shooting.

Rawdon Lee thought they never existed and suggested that Purcell Llewellin shared his opinion.

“As a fact, I do not believe the Russians ever had a setter of their own. For years Mr. Purcell Llewellin offered a prize for him at the Birmingham show, but in no instance was there an entry forth-coming. Possibly, in promising such a thing the Welsh squire was poking fun at the breed, and, in a way of his own, endeavouring to prove to the public what he thought himself, that such a thing as a “Russian setter” had only existence in fancy.” —History And Description Of The Modern Dogs (Sporting Division) Of Great Britain And Ireland, By Rawdon B. Lee

I believe that Idestone was correct. He believed that while some sportsmen may have shot over what they call Russian Setters, none were bred in Russia or by Russians.

“I have heard of Russian Setters, but I have never seen one worthy of the name, nor do I think that such an animal is bred or cultivated by the Muscovites.” —Idestone, The Dog

But if they were not from Russia, where did they come from? The most likely source was continental Europe. Rough-coated pointing dogs were quite common there and, in 1825, Barnabas Simonds even wrote about dogs he called “rough-Pointers” that were “…introduced to Suffolk by the late Earl of Powis, from Lorraine.” He goes on to say that the only reason they were imported was “…for the little Satisfaction of deceiving and surprising Strangers,” but then explains why they disappeared: “Sullenness and a violent attachment to mutton brought them into disgrace, and they have been discontinued for many Years” (A Treatise on Field Diversions by Barnabas Simonds, 1825).

Could Simonds be correct in stating who brought them into Britain and where they came from, but wrong when he says they’d been “discontinued?” Maybe some of them did manage to hang on, and perhaps some were bred in Britain and re-branded as “Russian Setters.”

Another possibility is that “Russian Setters” were created in Britain. It is almost certain that at some point in the past, either by accident or design, Pointers were crossed with curly-coated breeds like the Irish Water Spaniel. The results would have been, at least in part, pups with “rough” coats. Like the Pudelpointer, which was created by crossing Pointers to Pudels (not the “poodle” we know today, but an older type of waterdog known as Pudels in Germany), a Russian Setter could be created with little difficulty.

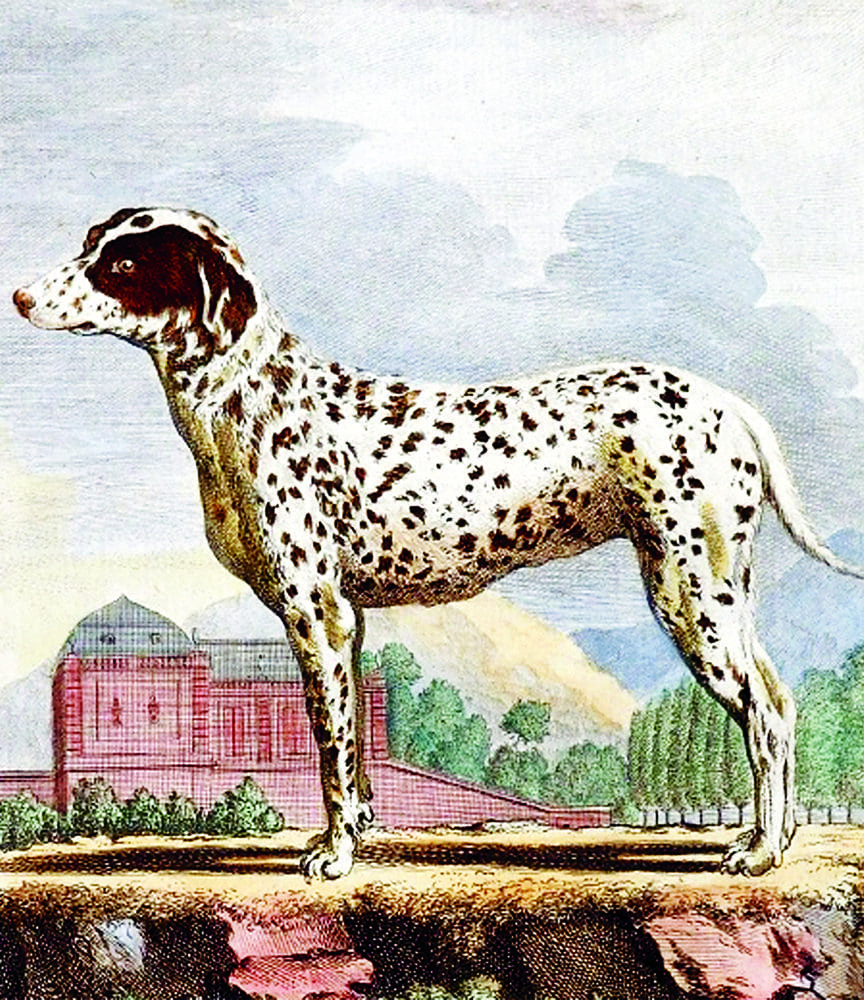

Another “unicorn” breed was the Braque du (or de) Bengale. In the late 1800s, dog shows in France and elsewhere accepted entries for what many assumed was a short-haired pointing dog from Bengal (modern-day Bangladesh and parts of eastern India).

The Braque du Bengale or Bengalese Pointer was said to have a coat like that of a spotted lynx. Others claimed that it was striped like a zebra or tiger. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Italian authors Ulisse Aldrovandi and Vita Bonfadini wrote about spotted or striped braques, and the French naturalist Alcide Orbigny even coined a Latin name for the breed, Canis avicularis bengalensis. He described it as slightly thinner than other braques, with a white coat covered with large brown spots, grey-brown ticking, and tan points on the eyes and legs. There are many more references and even several illustrations published in the sporting press that seem to prove that there were pointing dogs from the Indian subcontinent.

But Jean Castaing and other experts dismissed the idea. They point out that there has never been a tradition of hunting with pointing dogs in India and that there is no reason to believe that hunters there would have ever developed their breed of braque, let alone export it to Europe. The most logical explanation is that the name Braque du Bengale was given to any short-haired pointing dog with a strongly ticked or brindle coat. In the same way, people thought that anything with a rough coat was Russian or Polish, they assumed that any dog that looked like a lynx or a tiger must be from an exotic land in the East.

A curious footnote to the story of the Braque du Bengale involves the Dalmatian. Many histories of the Dalmatian claim that the Bengalese Pointer contributed to its makeup, a claim probably based on a passage found in Le Cabinet du Jeune Naturaliste, a book published in Paris in 1810. On page 122 of Volume Two, a new section opens with the title, “Le Braque du Bengale.” The text goes on to say: “This animal, sometimes erroneously called Danish, is very common in England…”

What is overlooked by many is that Le Cabinet du Jeune Naturaliste was a translation of The Naturalist’s Cabinet, published in England four years earlier. In the original, the title of the section is “The Dalmatian or Coach-Dog”. Nowhere in the text are Bengalese dogs ever mentioned. Clearly, whoever did the translation took a bit of literary license when he rendered “Dalmatian or Coach-Dog” as “Braque du Bengale.”

The Polish Waterdog is another breed that never really existed.

In a book called Die Kleine Jagd published in 1884, Friedrich Ernst Jester wrote about what he called the Polish or Hungarian Waterdog. He said that they were rare, but still found in “eastern regions.” He described them as having a coarse, brown and white coat, heavy eyebrows, and a moustache. He claimed they were “very similar to the French Griffon and the nose is often split… called Doppelnase (doublenose).” Jester’s account was not alone. Sprinkled throughout much of the old sporting literature, especially from Germany and eastern Europe, are other references to a Polish Waterdog. In a hunting encyclopedia published in the 1820s, Johann Matthäus Bechstein mentions a dog that comes from Poland and that by nature, willingly goes into the water. It is described as having long, curly hair with brown patches.

It is tempting to conclude from these and other sources that a breed of rough-haired waterdog existed in Poland until the late 1800s. But we must remember that from 1772 until the First World War, Poland was partitioned into areas controlled by Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

There were no kennel clubs there or any organized breeding systems and, at the time, hunters across Europe tended to call any rough-haired dog from the east a “Polish” or “Hungarian” or “Russian” Waterdog.

In Poland itself, the opinion of several authors was that so-called Polish Water Dogs came from elsewhere. In Nasze Psy – Vademecum Miłośnika Psa, a book published in Poland in 1933, author Stephen Błocki mentions Polskim Wodołazie (Polish Waterdogs), writing that they came to Poland via France or Hungary. Another author, Lubomir Smyczyński wrote in 1948 about a Wyżła Polski (Polish Pointer).

He indicates that it was not a breed but a type of dog found in Poland, Lithuania, and the other Baltic countries, and says that foreign authors, trying to figure out where they came from, just called them Polish Pointers. Other authors mention Polish Wirehaired Pointers and there was even an effort made in the 1960s to create a Polish Shorthaired Pointer. A group of enthusiasts led by the geneticist Janusza Mościckiego and breeder Kazimierz Tarnowski tried to develop what was essentially a Polish version of the German Shorthaired Pointer, but smaller and more resistant to the harsh weather conditions of Poland. Many dogs were bred in the 1970s and 1980s, but the program eventually ran out of steam and was abandoned.

For all the dogs lost to history—or perhaps lost to the lore of exotic breeds with no discernible proof of their existence in the first place—there remain some breeds that have fought the battle with extinction and survived. In the next issue, we will take a look at several breeds that, for all intents and purposes, went extinct, but were successfully revived or re-created through the tireless efforts of breeders and clubs.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.