American Woodcock Accumulate Lead According to Study

Using non-lead ammunition can decrease the impacts of toxic lead levels on this beloved upland bird species

Non-lead hunting ammunition has been mainstream, especially for waterfowl hunting, for over 20 years. Since the ban on lead ammunition for waterfowl hunting, many bird species have been conserved due to the decrease in lead on our landscapes like raptors, waterfowl, and scavenging birds; today, these critters are ambassadors for using non-lead ammunition when hunting.

But lead ammunition is still legal to use for upland bird hunting, including some spots in Wisconsin. As a result, lead continues to accumulate in places where upland hunters pursue birds. The American woodcock has flown under the radar in this regard. However, one team of researchers in Wisconsin noticed that woodcock accumulate high levels of lead in their bodies.

Sean Strom and his co-investigators published an article for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources titled “Lead Exposure in Wisconsin Birds” in 2008. Their study examined bald eagles, common loons, trumpeter swans, and the American woodcock. According to their work, 25 percent of recorded swan fatalities were due to lead toxicity. Likewise, 15 percent of eagles were dying due to lead. They noticed these fatalities increased significantly during November and December, which is exactly when hunting season rolls around in the midwest.

Their woodcock data was especially startling. The researchers learned that woodcock were accumulating lead on their historical breeding grounds and accumulated levels of lead in their bone tissue that would be toxic to waterfowl. This accumulation was present in all age classes of woodcock. Through their work, they were able to identify that the lead impacting woodcock was both sourced from local areas and introduced into their diet. The researchers suggest that we won’t see a decrease in the lead levels in woodcock unless “the amount of lead discharged into the Wisconsin environment is reduced.”

How Strom et. al collected their woodcock data

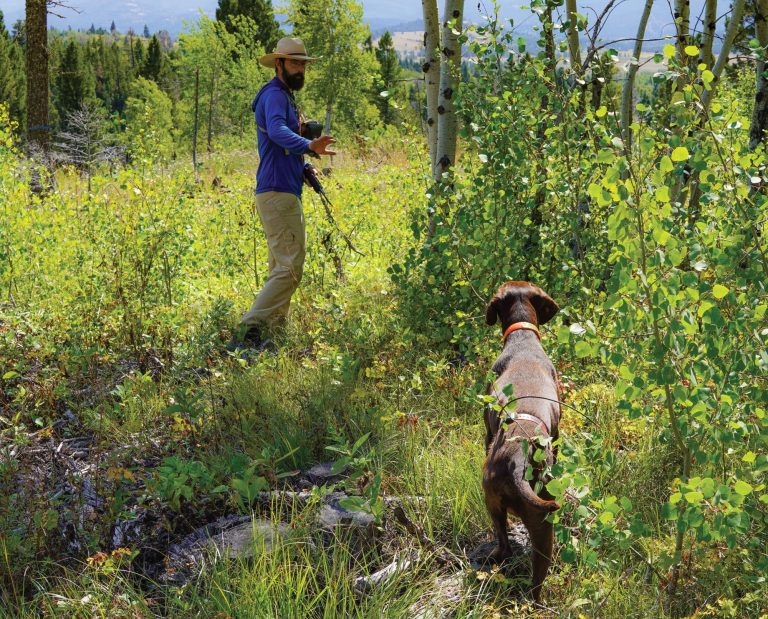

With a little help from some well-trained pointers, Strom and his team located adult woodcock, broods, and nests. They hunted adult woodcock with steel shot two weeks before their hunting season began from 1999 and 2001 in northern Wisconsin. The idea behind this was that by hunting prior to the season opening, they would focus their data collection on locally exposed birds and avoid collecting seasonal migrants. This is how they’d know if the lead exposure actually occurred in northern Wisconsin or if the birds were exposed in other locations.

In addition to adult woodcock, they also collected young-of-the-year from broods pointed by dogs in spring. One chick was selected at random for data collection purposes. This was another way to back up their theory that woodcock were being locally exposed to lead, not being exposed elsewhere and then migrating to Wisconsin.

Each bird sample was radiographed, dissected, and inspected for heavy metals including lead. In addition to reviewing digestive tracts of woodcock, the researchers also analyzed their bones for lead. Bone tissue was dried and pulverized so any lead present in the tissue could be weighed out.

Woodcock data analysis

After completing a thorough data analysis, the researchers found no lead pellets in any of the woodcock they sampled. However, different data collection locations had significantly different concentrations of lead in their local woodcock. This agreed with previous research from 1999 that found high concentrations of lead in woodcock young-of-the-year and chick bones.

Researchers found it a bit odd that none of their woodcock samples had any lead pellets in them. However, they theorized that this was due to the fact that woodcock don’t have a large gizzard, so pellets are voided from their body quickly after ingestion. Other species similar to woodcock like godwits, dowitchers, and snipe do have larger gizzards and researchers have found pellets in these species before. Therefore, the researchers believe that woodcock ingest pellets sometimes, but their tiny bodies just can’t handle storing the pellets within them.

Additionally, they found lead isotopes consistent with both natural soil levels of lead and lead shot from shotguns. Lead has four stable isotopes; some of these are found in nature, and others only occur in made-made substances like medical equipment or shot shells. Because these woodcock have both, scientists concluded that lead upland game shot cannot be ruled out of a source of lead exposure for woodcock.

“We have certainly documented that woodcock at all life stages have the ability to accumulate significant levels of lead,” said Sean Strom, the lead researcher for this study. “What we have not documented, nor have any of my colleagues, is whether the high lead levels are having an adverse health impact .”

Theories as to why woodcock have lead in them

Historically hunted woodcock lands have been accumulating lead from hunters since there’s been a woodcock season. As a result, there are larger concentrations of shotgun-sourced lead isotopes in these soils. We also know that earthworms make up approximately 90 percent of woodcock diets. Worms are known for their ability to soak up toxins including naturally-occurring and introduced lead.

“All we do know is that the stable isotope signatures observed in woodcock bones overlap between natural and anthropogenic ,” said Strom.

Does all this exposure mean that woodcocks have a high lead tolerance? Perhaps. But we don’t really know for sure quite yet. Their ability to survive with quantities of lead in their bones that would be toxic to waterfowl is quite impressive.

Some hunters aren’t too worried about consuming large quantities of woodcock meat. “We have no reason to believe hunters are at risk from eating woodcock,” said Strom, “We did test some breast muscle and the results came back very low.”

However, a study titled “Lead ammunition residues in the meat of hunted woodcock: a potential health risk to consumers” was published in the Italian Journal of Animal Science. That research team found that “woodcock meat derived from animals shot by traditional Pb ammunition retains a considerable quantity of metallic Pb,” mostly in pellet, fragmented pellet, or micro-fragment forms. They argue that “…regular woodcock meat consumers are exposed to real health risks.”

To me, it’s up to you whether or not you want to reduce your exposure to lead. If you’re nervous about it, consider switching to non-lead ammo for all of your hunting adventures. One can still be exposed to lead through rifle hunting; in fact, another study found that acidic venison marinades made lead more bioavailable. For example, if you hunt pheasant with lead ammunition and use a vinegar-based marinade, you’re likely going to be exposed to more lead than a hunter who uses non-lead ammo and uses cream-based marinades.

What does this mean for Wisconsin’s upland birds?

Have woodcock adapted to tolerate high levels of lead in their bodies due to their wormy diet? Maybe so. “The relationship between lead accumulation and health impacts (or lack thereof) in woodcock is still quite puzzling,” said Strom, “We don’t know why nor how young woodcock can accumulate the high levels we observed – we just know they can!”

Also, because this study only examined a few Wisconsin bird species, scientists aren’t quite sure to what degree other upland birds are being exposed to lead in the state. Are ruffed grouse being negatively impacted? What about the sharptails trying to repopulate the pine barrens of northern Wisconsin? If hunters used lead ammunition in historical grouse hunting grounds, then there may very well be high levels of lead in those environments that’s leading to lead toxicity in the birds we love. It’s important that we call on our local wildlife researchers and biologists to examine this topic and explore the impacts of lead poisoning across bird species in the midwest and beyond. Perhaps it’s high-time we advocate for requiring non-toxic ammunition for all bird hunting.

This fall, consider switching to non-lead ammunition if you haven’t already no matter where you live. Avoid contributing more lead into our natural environments, especially if you hunt these places often. Your favorite hunting spots and local juvenile woodcock will thank you.

Find a study that fits your agenda, I guess. Worms + dirt = lead

The segment on marinades was really impactful.

The source of the lead is still in question, however I have started to use non-toxic shot exclusively this season for my upland adventures . The cost of ammunition is the least of my expenses for most hunting trips. Fuel for the vehicle is the most.

Not being able to review the data, there is no way to judge the validity of the conclusions(?) – suggestions. The suggestion is that converting to nontoxic shot will reduce the lead accumulation in woodcock in the areas sampled. However, the long-term accumulation from naturally occurring lead in the environment will not be decreased. Is there data that show increased mortality from these high levels of lead? Comparative studies from other breeding areas in Canada and the US around the Great Lakes, with soils analyses, would certainly add to the plausability of the authors’ suggestions.

I have switched to bismuth shot for waterfowl & often use it for upland birds.