Home » Grouse Species » Prairie Chicken Hunting » The Lesser Prairie Chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus): A Prairie Gladiator

The Lesser Prairie Chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus): A Prairie Gladiator

- Climate Change Impact (Audubon) | +1.5°C - 31% Range Lost | +3.0°C - 61% Range Lost

Seth Owens is a wildlife photographer and Education and Outreach…

The future of the second-most imperiled grouse rides precariously on the prairie winds.

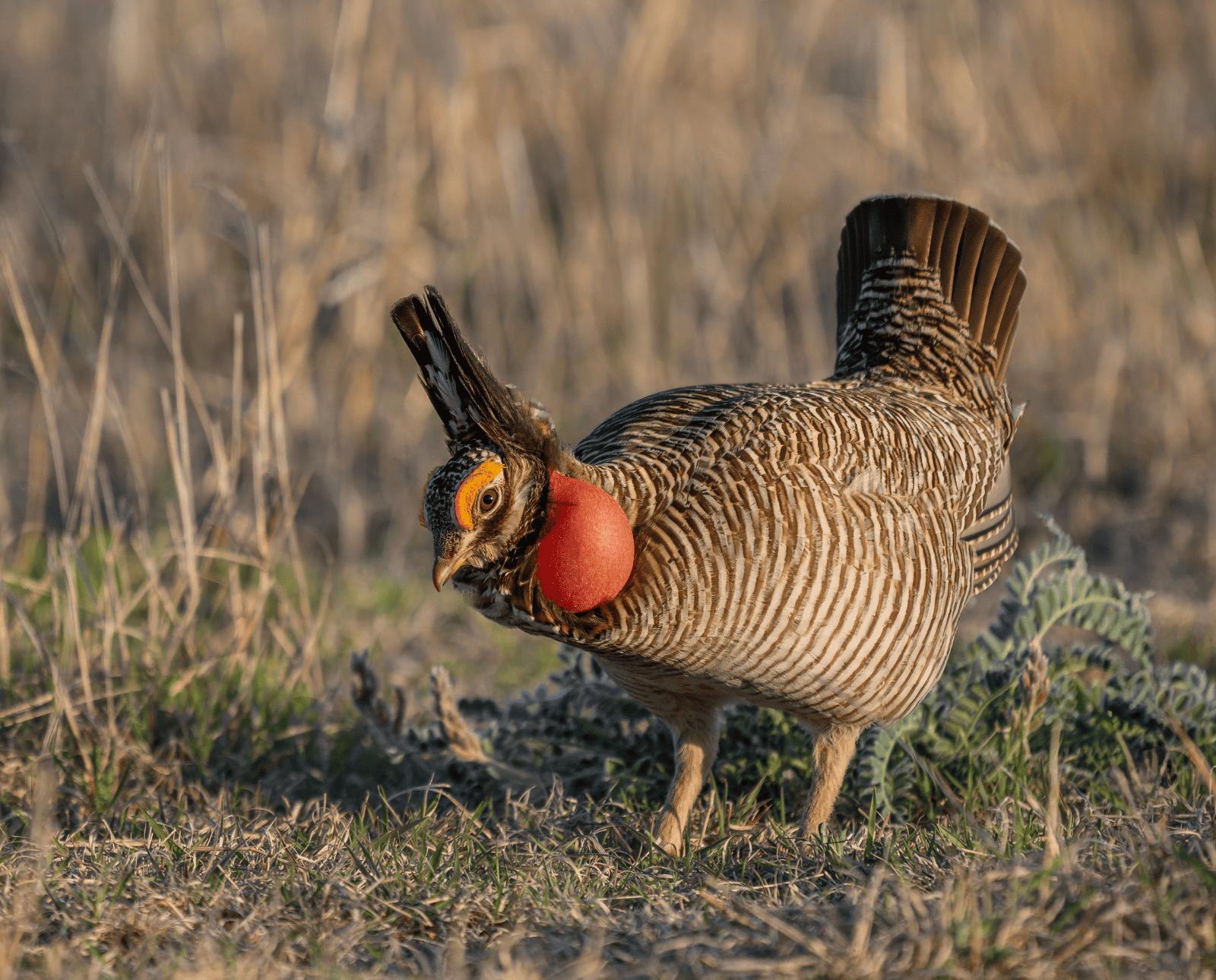

A bouncy, warbly sound erupts from the southern Great Plains. Another voice joins in. Then another, and another. Soon, the prairie is alive with the booms and cackles of Lesser Prairie-Chickens. With tails fanned wide and pinnae erect, they strut, stomp, and scrap in a flattened patch of grass.

This is a Lesser Prairie-Chicken lek, a lek belonging to the second most imperiled species of grouse in North America. It’s behind only its western neighbor, the Gunnison Sage-Grouse. There was a time when hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Lesser Prairie-Chickens called the plains of Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico home. Today, they occupy a fraction of that range. Their population pales in comparison.

Lesser Prairie-Chickens are incredible animals, and I hope you experience that wiggly-warble of theirs. But their future is in the air, it rides precariously on that Kansas wind.

Lesser Prairie Chicken Information

| Characteristic | Details |

| Scientific Name | Tympanuchus pallidicinctus “Tympanuchus” – To have a drum “Pallid-” – Pale “-cinctus” – banded “Pale-Banded Drum-Bearer” |

| Taxonomic Order and Family | Order Galliformes, Family Phasianidae |

| Average Body Measurements | Length: 15 to 16 inches (38-41 cm) Weight: 22–29 oz (628–813 g) Wingspan: 24.8 in (63 cm) On average, adult males are larger than females. |

| Egg Characteristics | Ovate egg, similar to domestic chicken eggs. Color ranges from a light cream to a pale sand color, sometimes with fine speckles of olive or brown. |

| Nest Characteristics | A shallow depression in soil, lined with feathers and vegetation. Roughly 8 inches wide and 4 inches deep. |

| Diet | Juvenile diet is heavily composed of insects, adult diet is variable by location, but is a mixture of seeds, vegetation, and invertebrates. |

| Habitat | Expansive grasslands, especially those dominated by shortgrass prairie species. |

| Range | Historic range covered a vast area of Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. Current ranges exist in the same states, but their sizes are a fraction of the historical amount. |

| Estimated Populatin | Approximately 28,000. Historic estimates were in the millions. |

| Conservation Status | Vulnerable |

| Conservation Concerns | Habitat conversion and degradation has seriously impacted breeding, nesting, and brood-rearing habitats. |

| Similar Species | Greater Prairie-Chicken and Sharp-tailed Grouse |

Lesser Prairie Chicken Physical Description

The lesser prairie-chicken is a medium-sized, plump looking grouse covered in dark brown to lightish-brown and white bands. Females and males have a white throat with a dark cheek and yellow feet. Males have magenta-orange colored air sacs, more specifically called gular sacs, on their necks. Males also have pinnae, or feathers that somewhat resemble rabbit ears when erect, at the base of their heads, as well as yellow eye combs.

Rather than having wispy or pointed tails like sage or sharptail grouse, the lesser prairie chicken’s dark-colored tails are squared off.

Visually speaking, there are three main differences between lesser and greater prairie chickens: their color, size, and barring patterns. Greaters are larger, darker, and more heavily barred. Lessers are smaller, lighter-colored, and have less pronounced barring. Additionally, greater prairie chicken’s gular sacs are strictly orange and nearly identical in color to their eye combs. Lessers’ gular sacs are more reddish-orange or even purplish. That said, the biggest difference between greater and lesser prairie chickens are their ranges; they do not overlap.

Lek Behaviors

Like many grouse, lesser prairie chickens are a lekking species. Species like sage grouse, sharptail, and prairie chickens in North America and black grouse and capercaillie in Eurasia all gather on leks during the breeding season. On leks, males compete for the dominant status as the fittest one in the region.

The fittest lessers have an extravagant display. A male raises his pinnae, flares his fanned tail, stomps his feet rapidly, inflates his air sacs, and lets loose a spring-like boom. Males establish loose territories on the lekking grounds. The prime contenders are in the center of the hayed-down grass, and the younger and less dominant males are on the outskirts.

Skirmishes frequently break out on the boundaries of these territories. Dominant males will viciously pursue the intruder and engage in aerial combat over border disputes. These battles in grassland arenas ramp up dramatically when a female wanders through the lek. Females remain on the outskirts of leks, but walk through the thick of the action when she selects a contender to breed with.

Nesting And Brooding Behaviors

In a short encounter, the copulation concludes, and the female abandons the lek for the season. A hen will select an area of grassland with adequate overhead and horizontal cover. She scrapes a small depression in the soil, lining it with grasses, forbs, leaves, and feathers, and lays her eggs. She will lay one egg per day until she reaches a clutch of 11-14. The 24- to 26-day incubation period begins after she lays her final egg.

Following incubation, chicks all hatch at a similar time. These chicks are precocial, meaning they are covered in down feathers, with open eyes, and ready to face the world on their own with guidance from their mother. Every chick will leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching.

Hens guide their young to a suitable brood-rearing habitat, often a place with a dense overhead cover, a navigable understory, and ample insects and forbs for chicks to eat to meet their high protein demands. Under prime conditions and ample resources, chicks develop incredibly quickly. They will be capable of short bursts of flight within about 14 days, and reach 90 percent of their expected adult body mass within 80 days.

It’s a dangerous world on the prairies, but with good conditions and a bit of luck, chicks will survive. After about 12 to 15 weeks, broods begin to break up and the young gain full independence from their mom.

Lesser Prairie Chicken Habitat and Diet

Lessers require vast expanses of grassland and prairie. Pre-European contact, their habitat was dominated by mixed prairies of sand sagebrush-bluestem and shinnery oak-bluestem communities. Prairie conditions have changed since humans expanded into the plains. Lessers are more common today in areas with small shrubs and mixed grass vegetation on sandier soils, sometimes mixed with chunks of short-grass or mixed-grass habitats.

Different regional populations prefer different prairie compositions. In their southern ranges, populations prefer habitats more similar to their pre-contact habitat of sand sagebrush and shinnery oak-bluestem communities. CRP parcels, often composed of grass mixes with various native grasses and forbs, have been used as nesting and brood-rearing cover in the northern fringes of their range.

In Texas, intermixed parcels of agricultural small grains (between five to 37 percent of land in the region) were shown to be more productive for Lessers than areas with 100 percent native rangeland. However, areas with less than 63 percent native rangeland appeared to be void of Lesser Prairie-Chickens.

Insects, forbs, vegetation, seeds, and agricultural grains make up the main composition of a Lesser’s diet throughout its range. Different ratios of plant matter to insects are observed throughout the seasons. In summer months, adults tend to eat a higher proportion of invertebrate matter. In the winter and autumn, they tend to eat more plant matter.

Historical And Current Ranges

Historically, Lessers resided across a huge swath of prairie, spanning from central Texas, into New Mexico, across much of Oklahoma and Kansas. Today, we’re limited to a few fractured pieces of habitat, a fraction of where they should be. Populations are no longer strong enough to support hunting, and a few small decisions on a parcel of land could be the difference between life and death for regional groups of lessers.

The current lesser prairie chicken is currently located in Colorado, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and New Mexico. The bird lives in small pockets of habitat within each state’s boundary. Lessers are somewhat adaptable because they utilize small proportions of interspersed agricultural cropland and CRP pastures. However, they are not immune to the rapid changes we are seeing across our prairies.

The lek I viewed birds on, and so many others, exist on private land. These are often cattle pastures or hayfields. Conservation-minded landowners are key to protecting our prairies and preserving lesser prairie-chicken populations. Removing all disturbance and activity from our prairies is not the solution towards successfully restoring grassland bird populations. A stagnant prairie is a dead prairie, and conservation-minded cattle production is a great tool for maintaining and restoring grassland health.

Lesser Prairie-Chicken Conservation Concerns

Prairie chickens are a controversial subject across much of their range. Talking chickens is a fantastic litmus test to gauge a person’s thoughts toward land conservation, the Endangered Species Act, and other conservation concerns. The long-and-short of it is that lesser prairie-chickens are struggling across large portions of their range.

There are a huge number of issues that have damaged the populations of lessers. However, the main smoking gun is the range-wide loss, degradation, and fragmentation of habitat. The conversion of grassland to agriculture, fragmentation of habitat due to roads, renewable resource infrastructure, and oil and mineral operations can substantially impact this sensitive species.

From Native American tribes pulling inspiration from displays for their ceremonies for thousands of years, to people flocking across the world to watch them dance today, lesser prairie chickens have been and will be appreciated each year. And there are plenty of people swinging for these prairie dancers.

State and federal organizations are invested in keeping Lessers alive. NGOs, like Pheasants Forever, Working Lands for Wildlife, National Audubon Society, North American Grouse Partnership, and more are putting boots on the ground to keep these birds around. Habitat projects, reintroductions, and continued monitoring is often a thankless task, but these folks wake up every morning ready to fight to keep the Lesser Prairie-Chicken forever.

The future of this prairie gladiator is not set in stone. Like all prairie grouse species, Lessers are sensitive to extreme disturbance, habitat loss, and prairie fragmentation. Humans are a huge reason for the declines in Lesser Prairie Chickens. However, we can also be the solution.

Seth Owens is a wildlife photographer and Education and Outreach Coordinator for North Dakota Pheasants Forever. When he's not chasing birds with a shotgun and his dog, Tanka, he's pursuing grouse and waterfowl with his camera across North America. He's currently photographed 8 out of 12 North American grouse, and is well on his way to photographing the rest. He enjoys the silent solitude of watching the sun rise over the grasslands or the awe-inspiring sounds of the woodlands. Wildlife photography isn't the only reason he explores North America's wild places, but it's a fantastic excuse!