Understanding Tracks and Other Game Bird Signs

Identifying clues left in the deserts, mountains, uplands and woods when bird hunting

“I’ve got tracks!” I wasn’t paying much attention to the dog who had become birdy. I let my eyes wander along the ground. The small four-toed imprints were becoming sporadic. I felt like we were getting close. Angus, Hutch’s wirehaired pointer, froze in midstride. The birds caught me by surprise and a whir of wingbeats broke the silence. Seconds later, the smell of spent gunpowder filled the air and two bobwhite quail lay on the ground. Each of us had connected. Did the quail tracks play a role in our success?

Definitely.

Tracks are the imprints left behind in soil, snow, mud, sand or other ground surfaces. When identified correctly, tracks are a good indicator that upland birds are in the area. Tracking is the science and art of observing animal tracks and other associated signs, with the goal of gaining an understanding of the landscape and of the animal being tracked.

Upland birds are a good core group to focus on; their footprints are simpler to identify than other groups of birds because of their relatively simple foot structure. Upland birds are generous to wingshooters as they leave behind signs as they walk, run, rove, forage and roost.

Bird tracks are classified into five categories: Classic or Standard, Game Bird, Webbed, Totipalmate and Zygodactyl. We as bird hunters only need to focus on Game Bird Tracks, with a hint of discussion on Classic Tracks.

Classic or standard bird tracks

These tracks have three toes pointing forward and one long toe pointing backward. This is common in perching birds such as doves, pigeons, crows and many others. The toes are narrow, with longer toes to grip slender twigs. Doves and pigeons, which spend a lot of time rambling across the ground feeding, usually have wider footprints.

Game bird tracks

Game bird tracks are like classic tracks, except the toe in the back is much smaller and may not touch the ground at all or may be absent altogether. It helps to know that bird toes are numbered from the back toe (referred to as “toe 1” or the halix) to the outside. The outermost toe is called “toe 4.”

This group includes quail, ring-necked pheasants, grouse, partridge, turkey, rails and a few others.

Get a feel of the land: Know the birds

With so many possible bird species, identifying game bird tracks can be tricky. It’s important to consider all the evidence. When bird hunters come across tracks, a closer look should be taken into the surrounding area. Are they in the prairies, grasslands or forest? It helps to study the natural history of the birds being hunted in the area and to understand their preferred range and niche. One’s knowledge base and experience in the area is crucial in helping pinpoint the type of species that frequent specific habitat, cover and food sources. This is especially important when hunting in areas where upland bird species overlap.

Walking or running: Pattern the tracks

A note of caution: birds are dynamic, energetic creatures that can and often do switch between different gaits as they move about the landscape feeding, foraging and moving from one location to another.

To make a positive ID, hunters need to gather a little more evidence. Most importantly — follow and trust the dogs.

When bird hunters come across single footprints that are regularly spaced out, the bird is walking. Grouse (Dusky, Ruffed, Spruce, Sharp-tailed, Sage), mourning doves, and pigeons fall into this category.

Running (all pheasant hunters have dealt with running roosters!) is another mode of locomotion used by game birds that spend lots of time on the ground. It is differentiated from walking by the distance between each track as the trails left by running birds are similar but the individual tracks will be spaced farther apart.

Quail spend most of their time on the ground. Their tracks are usually found in a line because they run rather than hop. Public land bobwhite quail travel in coveys and run across the ground from the shelter of one shrubby patch to another. Tracks in the dirt, sand or snow can be a good indicator that coveys may be in the area.

Search for signs that aren’t footprints

Besides tracks, game birds leave traces of their presence in the uplands everywhere they go. From scat to feathers to roosting sites, identifying signs that aren’t footprints will help bird hunters become familiar with game bird habits and make them better hunters.

Identifying roost rings

Roost rings are circular piles of droppings left by a roosting covey of game birds. Coveys roost in a circle with all individual birds facing outward from the center of the circle. This is done to conserve body heat and provide 360-degree surveillance of any approaching predators. Feathers and small piles of green-and-white droppings are clues to roosting sites.

Chukars, Hungarian (“Huns”) or gray partridge and bobwhite quail are known to roost in a circle. According to biologists, at least seven quail are needed to form a circle so that their tails converge and trap the heat from the birds’ droppings. Hunters should consider not shooting a covey down to fewer than five or six birds, or the covey’s ability to reestablish themselves during the off-season could be adversely affected. Scattering a covey late in the day and early evening may also inhibit a covey from regrouping, thus diminishing their chance for survival overnight, especially during the cold winter months.

Identifying dust baths

Dust baths are characterized by an area where game birds cower close to the ground and vigorously roll their bodies and flap their wings in dust, dry earth or sand, leaving imprints in the ground. The purpose behind this is to remove parasites from feathers as well as a maintenance behavior to maintain healthy feathers. Quail and ruffed grouse are examples of upland birds that practice dust bathing.

A group of quail will select an area where the ground has been freshly turned or is soft. Using their underbellies, the quail will burrow downward into the soil. The birds will then wriggle about leaving circular indentations in the ground of their dusting activity.

Ruffed grouse literature seems to indicate the “King of the Game Birds” likes taking dust baths while basking in the sun’s rays and suitable material. The material utilized varies, with the primary requirement being looseness and dryness. Dry, rotten wood of old stumps and logs are common as is fine, dry earth.

Drumming logs and sites

Drumming logs and sites are easily identified by the piles of grouse droppings on them, and occasional feathers. The location of the drumming log simulates the epicenter of that grouse’s “territory.”

Using snow for clarity

Snow can be a weather bomb (blizzards) and ruin or slow down hunts. As an upside, snow can also be magical in helping bird hunters by revealing wildlife activity with forensic clarity. It acts as nature’s fingerprint powder. Hunting in the snow allows us to see “snow angels” complete with the wing and tail marks of a pheasant or grouse. Without snow, these upland field dramas would surely go unrecorded in nature’s activity log.

Grouse burrow under the snow to roost. Often, grouse hunters can see a track left behind by a grouse that was sitting in the snow with just its head poking above the white powdery surface to conserve energy.

Wing prints are visible on the snowy ground, heading in the direction the grouse or game bird left the roost. Food bits knocked from trees are additional clues that show the presence and activity of grouse in an area. These clues left in the snow allow hunters to better understand their upland quarry.

Identifying bird droppings

Droppings (“scat”) can signal if birds are in the area. Look at the shape and size to help identify the upland game bird species. Ask questions. How moist or dry are the droppings?

Savvy American woodcock hunters will look for the half-dollar-sized white “splash” indicative of timberdoodle droppings to help narrow the search for occupied habitat.

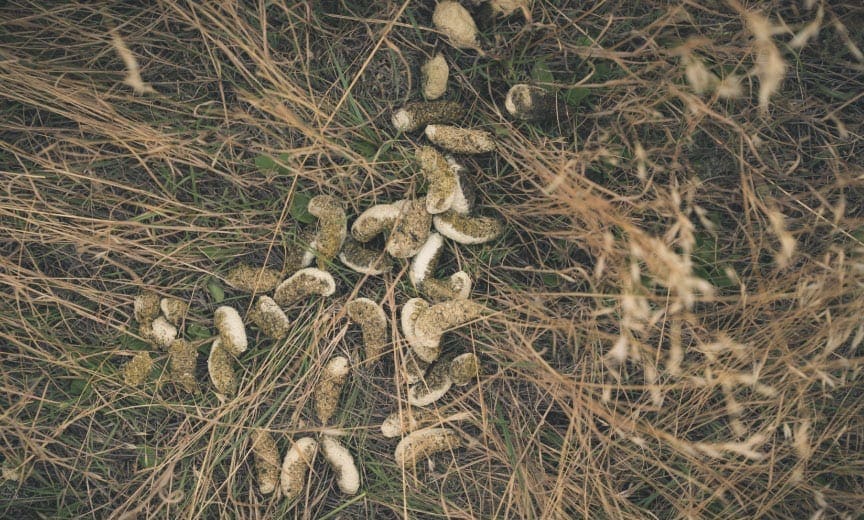

Sage grouse scat falls into four categories. Upland hunters will likely encounter three of these as the first is specific to incubating females which will be during the spring and/or mating season.

Cecal tar is common in winter when birds are eating 100 percent sage leaves and their digestive systems are separating volatile oils from digestible parts.

Fall foraging scat consists of a single dropping which indicates that sage-grouse are on the move as they forage.

Winter scat is generally shaped like a Cheeto™ and, upon examination, is exclusively digested sagebrush leaves.

Winter scat shows evidence of a uniquely designed digestive system. Terpenes contained in sagebrush leaves are segregated in the gut (cecal) and excreted separately. No other animal can live on 100 percent sagebrush; sheep, elk, and antelope mix it together with other vegetation.

Bird tracking skills should deepen awareness and the understanding of wildlife among upland bird hunters and helps develop competency in hunting. The deeper the understanding and knowledge a bird hunter has, the better experience they will have in the field. Let the tracks and signs tell their stories.

An excellent read and resource for upland bird hunters is “Tracks and Tracking” by Josef Brunner. Published in 1909, Brunner was a German tracker who wanted to better his chances at finding game by understanding their tracks. All hunters and outdoorsmen can benefit from reading this book.

The book is divided into two parts. Part One includes medium and big-game tracks. Part Two titled “Feathered Tracks” includes various types of upland game such as grouse, pheasant, quail, turkey and woodcock as well as waterfowl.

“Tracks and Tracking” can also be located and downloaded for free at www.gutenberg.org