Home » Woodcock Hunting » Aging and Sexing American Woodcock

Aging and Sexing American Woodcock

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was…

Learn how to identify male or female woodcock and adult and juvenile woodcock with these steps and charts

“A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” is a common phrase most folks are familiar with. From a sustainability standpoint, it’s easy to understand that leaving more birds on the landscape than you take is something worth valuing. However, when we are lucky enough to have a bird in the hand, how do we begin to identify what that bird is?

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Hopefully, if you’re an upland hunter, you already know how to identify a game bird to species. Given that hunting regulations are almost always species-specific, it’s our responsibility to know what’s flushing in front of us before pulling the trigger, especially when multiple species can look incredibly similar. Wilson’s snipe come to mind as an example because they share their favorite habitats with federally protected shorebird species. Luckily, when hunting American woodcock, you probably won’t run into any lookalikes; I can’t imagine anyone’s ever mistaken a ruffed grouse for a woodcock.

When your dog retrieves a woodcock to hand, it’s nearly impossible not to take a moment to admire the bird. Long bill, tiny feet, feathery details, and the lightness of its body; can you believe this handful of hollow bones and wild meat flew hundreds of miles twice a year, only to find a final resting place in your vest? Paying attention to the little details of this remarkable bird can tell you more about that individual’s life, too. Is it a male or a female? Adult or a juvenile? Here are some tips for deepening your knowledge about the woodcock who will feed your family this fall.

Telling a Male Woodcock from a Female Woodcock

American woodcock are sexually dimorphic. This means that males and females are different from each other. In the case of the American woodcock, females are larger than males in just about every way, even though they look nearly identical. Interestingly, Eurasian woodcock are the opposite; males are much larger than females.

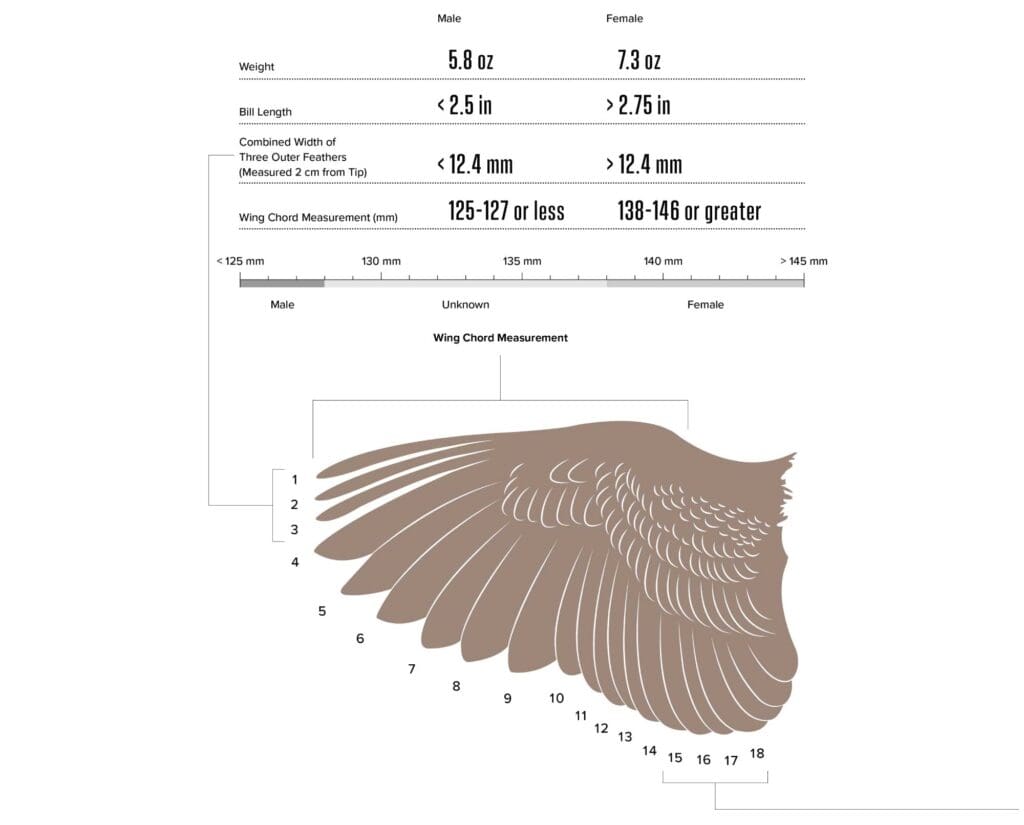

When determining whether your bird is a male or female, start by looking at the wings. “You can get all this information from a wing,” said Andrew Weik, a former American Woodcock Society Regional Wildlife Biologist, in a YouTube video from 2015. He’s referencing Greg F. Sepik’s handbook, A Woodcock in the Hand. “When we determine the sex of a bird from a wing, we look at the three primary wing feathers.” The three primaries that Weik is referring to are the three outermost wing feathers, the farthest flight feathers from the woodcock’s shoulder. In the video, he compares the width and length of these three feathers. A male woodcock’s three outer primaries are shorter and narrower than a female’s. You can see the difference at a glance, but researchers in Dr. Erik Blomberg’s lab at the University of Maine get a little more specific.

“There are three things I look for,” said Colby Slezak, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rhode Island who works with Dr. Blomberg. “Female bills are typically greater than 70 mm, wing chord measurements are typically more than 139 mm, and width of the outer three primaries is greater than 13 mm.” These specific numbers help researchers tell the difference between birds when the size difference isn’t as exaggerated, like between slightly larger males and slightly smaller females.

“Females are heavier as well, typically weighing approximately 210 grams,” Slezak added.

Weik has a neat way to measure bill length in the field, too. If you’re out hunting, “take out a greenback,” he said, “and slide your currency into the woodcock’s bill . If it’s up tight to its face and the upper mandible comes up short, it’s a male. You’ll notice that the female’s larger, longer bill will reach the edge or go past the edge of the dollar bill.”

Telling an Adult Woodcock from a Juvenile Woodcock

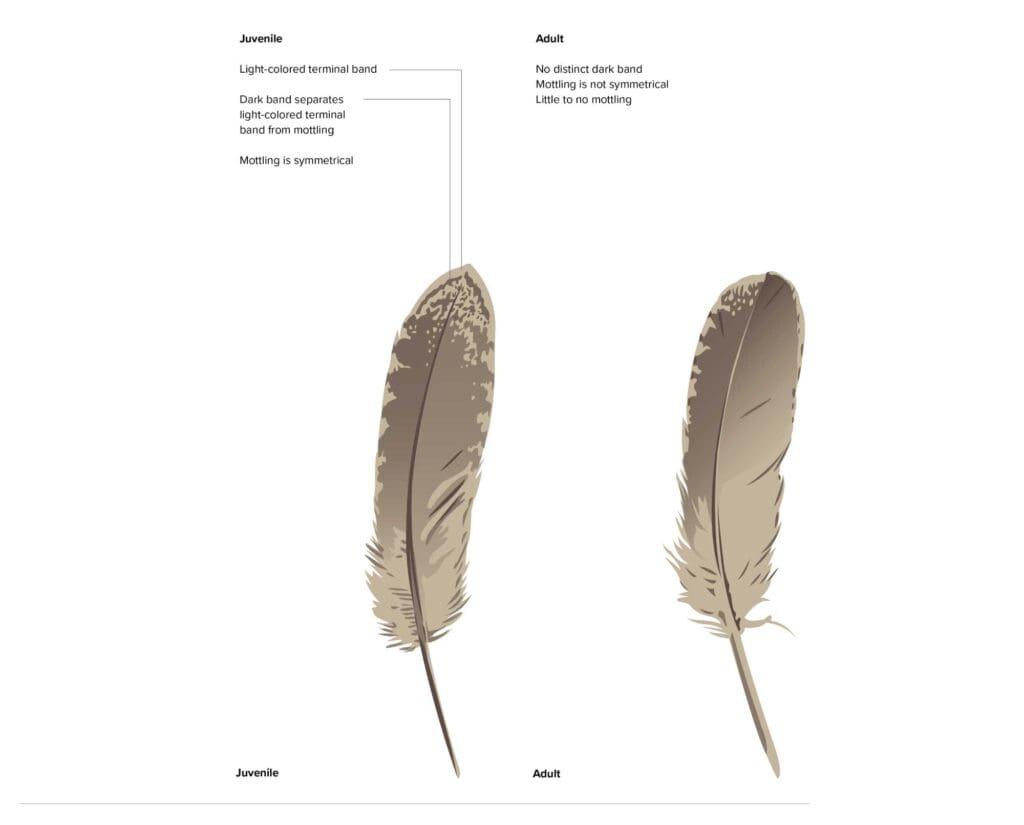

“You can tell adult from juvenile woodcock based on patterning found on feathers 15-18,” said Slezak. To locate feathers 15-18, count down from the outermost wing feather until you hit feathers 15, 16, 17, and 18. These are a set of secondary wing feathers. Slezak explains, “Juveniles have a light-colored terminal band and mottling on the feather.” Adults do not. Instead, adult woodcock have no distinct dark band, and if they have any mottling, it’s asymmetrical.

“That nice, bright, even, buffy tip stands right out,” said Weik. “Just under that buffy tip, it’s nice and dark. It’s a nice contrast between the buffy tip and the dark feather.” He mentions that juvenile birds have more arrow-shaped feather tips, too. “Adult birds will have no distinct buffy tip or much less. Also, the feathers tend to be narrower on one side of the rachis, or that center line, and wider on the other.”

In the video, Weik takes his wing analysis a step further. He explains that woodcock, just like other birds, experience an annual molt. However, they don’t lose all their flight feathers at once like some birds do; instead, they lose “one flight feather on a wing at a time, so they are always capable of flying.” On the adult female woodcock he uses as an example in the video, it’s apparent that she didn’t molt all of her flight feathers that year. Her old, worn feathers are light brown, and her new ones are dark brown. “It’s been a dry summer here in Minnesota, and when it’s dry, there’s not as much food available to woodcock. This bird didn’t have enough energy to replace some of these feathers.” As a result, that female only grew a few new feathers instead of replacing all of her flight feathers prior to the fall woodcock migration.

The next time you find an American woodcock in your hand, take a look at its wings, bill, and overall size prior to sticking it in your vest. Knowing the age and sex of your woodcock helps you build local knowledge about the birds that live in your favorite woodcock covers, and it’ll likely make you appreciate them even more, too. The more we understand about the birds we love, the more we can appreciate the lives they gave up for us.

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was born in Maryland and raised in southern Wisconsin, where she also studied wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2018, she moved to Gunnison, Colorado to earn her master's in public land management from Western Colorado University. Gabby still lives there today and shares 11 acres with eight dogs, five horses, and three cats. She herds cows for a local rancher on the side.