Home » Waterfowl Hunting » Northern Shoveler Species Profile

Northern Shoveler Species Profile

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to…

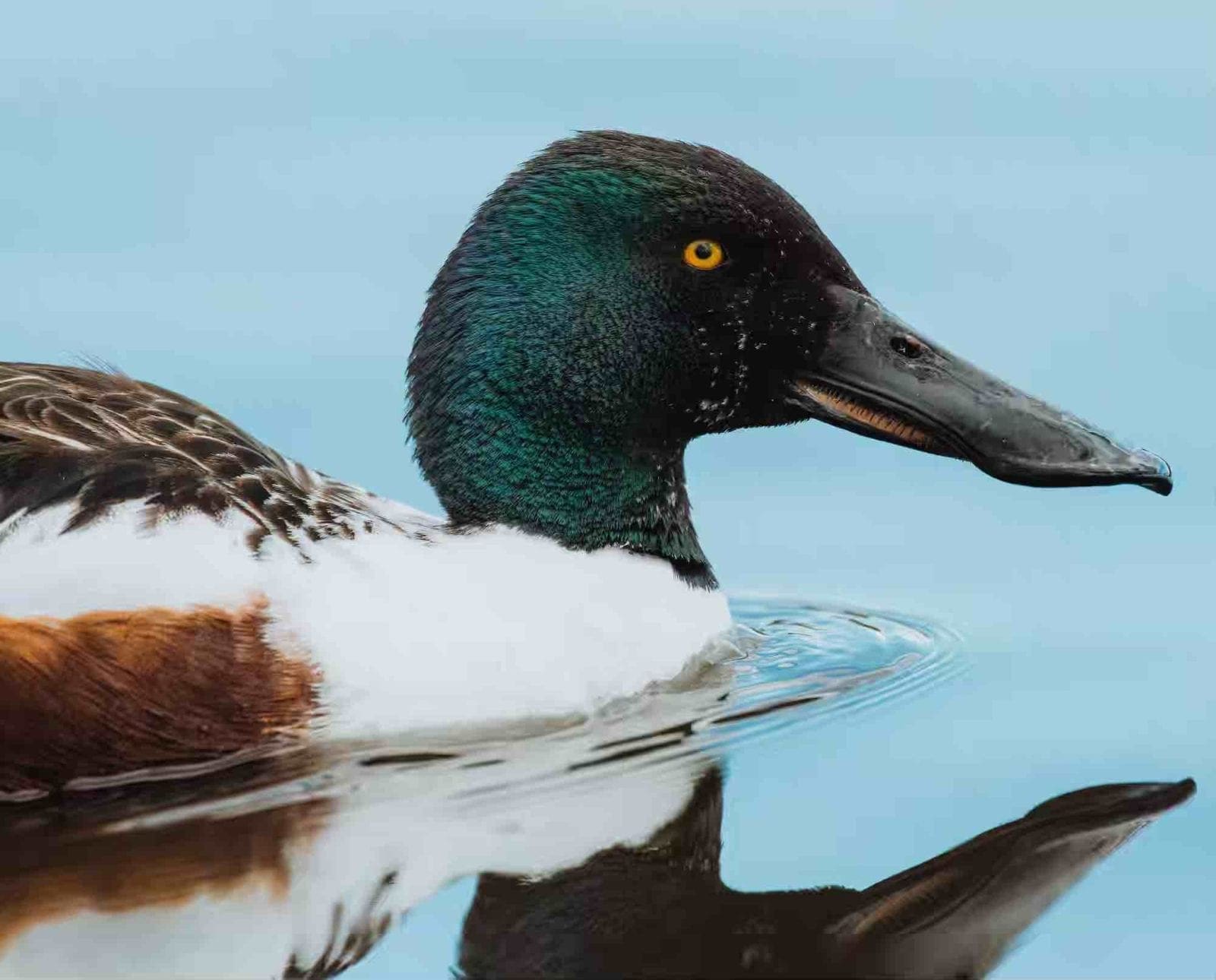

Learn how to identify and hunt the duck with the unmistakable face

You know how sometimes you meet someone with an unforgettable trait? The northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata) is like that. This strange-looking duck sports a huge bill that frankly looks like it was put on the wrong animal. This unique feature has earned it the nickname of “spoonbill” or “spoonie” to many waterfowlers. All loud-mouth jokes aside, the shoveler is a very interesting animal with a unique adaptation.

Description and life history of the northern shoveler

The northern shoveler is a medium-sized duck that measures about 18 to 19 inches long and weighs about 1.5 pounds (NatureServe 2020). Its most recognizable feature is a large, spoon-shaped bill, which helps this dabbling duck to feed very efficiently. The bill is lined with comb-like appendages (called lamellae) along the side that essentially filter out small invertebrates and food particles as it skims along the surface. Drake bills are dark black, while hen bills are orange. Breeding drakes have white breasts with black backs and wings, rusty brown-colored sides and bellies, dark iridescent green heads, and orange legs and feet (All About Birds, 2020). When flying, breeding drakes reveal their light blue shoulder patch and green secondary feathers along the fringe, just like the blue-winged teal. Hens have feathers that are mostly speckled brown and cream; they sport a light blue wing patch and have orange legs and feet. Although shovelers resemble mallards in many ways, they are actually much more closely related to teal.

Northern shovelers form pairs in late winter and numerous drakes will attempt to court a hen. When they arrive at their northern breeding areas, hens construct a shallow ground nest lined with plant materials and feathers in close proximity to water. They usually lay 8 to 12 olive-colored eggs and incubate them for 23 to 25 days (All About Birds, 2020; NatureServe, 2020). Within a few hours of hatching, the hen leads the ducklings to water. The young birds can fly about 52 to 60 days after hatching (National Audubon Society, 2020).

The northern shoveler’s unique-looking bill provides a very effective method of feeding. It’s a true dabbling duck that rarely dives or even tips down into the water. They simply submerge their open bill just under the surface of the water and paddle forward, sieving out anything it comes across. Flocks sometimes swim in tight circles to churn up muddy bottoms so that they can filter out small food particles as they go. Typical foods include seeds of various plants (such as sedges, bulrushes, pondweeds, smartweeds), duckweed, algae, and aquatic insects, mollusks, or crustaceans (NatureServe, 2020). During the winter, their diet switches to an aquatic invertebrate-heavy mix.

Most of the common waterfowl predators (like raccoons, skunks, foxes, coyotes, weasels, hawks, and owls) also prey on northern shovelers at some point in their life. But the risks are highest when hens are nesting, eggs are laid, or ducklings are young.

Range and habitat of the northern shoveler

Northern shovelers occur across North America, Eurasia, Africa, and even the northern reaches of South America. Within North America, they have separate breeding and wintering areas. During the summer breeding season, they can occur anywhere from Alaska to western/central Canada to the intermountain and Great Plains states (National Audubon Society 2020). The primary breeding clusters occur in the prairie pothole region and the great grasslands/parklands of Alberta and Saskatchewan, where shallow marshes provide abundant nesting habitat. During migration, they fly south to spend the winter along the West Coast, Gulf Coast, and throughout Mexico and some of Central America.

During the summer breeding season, northern shovelers prefer to use freshwater lakes, ponds, marshes, and creeks to nest and raise their young. Submerged and emergent vegetation is common in these areas. In the winter and during migration, they occupy freshwater marshes, lakes, wetlands, and flooded fields in addition to saltwater estuaries, bays, lagoons, and tidal flats (NatureServe, 2020; All About Birds, 2020). It’s not uncommon to find them using agricultural, stormwater, or wastewater ponds that other waterfowl might avoid (National Audubon Society, 2020).

Conservation issues for the northern shoveler

The northern shoveler is a common duck species with few conservation concerns. It has an estimated global breeding population of 4.5 million birds that was pretty stable between 1966 and 2015 (All About Birds, 2020). In fact, their population peaked in 2007 and again in 2009. It is listed as globally secure and of Least Concern by the IUCN Red List (NatureServe, 2020). Between 2012 and 2016, hunters harvested about 706,000 birds annually (All About Birds, 2020).

Hunting opportunities for the northern shoveler

Northern shovelers tend to migrate through the Pacific or Central flyways as they depart their summer breeding areas. Common wintering areas include California, Arizona, and the Gulf States (e.g., Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, etc.). As such, you likely have the best opportunities to hunt these ducks in these flyways and states. They tend to have a longer migration period too, so you may have shots from opening day to early winter.

Equipment and bag limits

Because northern shovelers are fairly common ducks and occur across a large area, you don’t need a lot of specialized gear to hunt them effectively. Besides your hunting license and duck stamp, you really only need a shotgun, decoys, a pair of waders, and camouflage clothing. These ducks aren’t particularly big, so a 12 gauge shotgun loaded with 3-inch shells of size three non-toxic shot is about as powerful a setup that you could need. A mix of puddle duck decoys is all you need for hunting shovelers, and they usually decoy easily.

Because hens and eclipse drakes resemble mallard hens and fast-moving drakes can even pass for mallard drakes in low light conditions, you’re likely to bag a few spoonbills when hunting a mixed bag of puddle ducks. Northern shovelers are not specifically addressed in many state regulations, but always check your specific state and hunting location for the current limit.

Northern shoveler hunting techniques

As mentioned above, northern shovelers tend to decoy fairly easily with the right setups. Because they associate with other ducks and will respond well to mallard decoys, you can often get by with just a general mix of puddle duck decoys rather than having to buy shoveler-specific decoys. Toss in a few teal decoys while you’re at it for a realistic and attractive-looking spread.

During the fall migration, ideal decoy locations include shallow marshes, sloughs, and prairie wetlands. Use waders to place your decoys in shallow water with muddy bottoms, as they likely support a lot of insect life that will attract the ducks. Given their close relation to teal species, it shouldn’t be a surprise that they can be swift fliers. For crossing shots, make sure to lead them appropriately.

Although they can have a bad reputation in terms of their meat quality (many other ducks that eat crustaceans and insects do too), don’t let that hold you back. Everyone’s taste is subjective, and you might find that you really enjoy them on the dinner table.

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to several outdoor manufacturers, hunting shows, publications, and blogs. He is an avid small game, turkey, and whitetail hunter from northern Minnesota and loves managing habitat almost as much as hunting. Ryan is also passionate about helping other adults experience the outdoors for their first time, which spurred him to launch Zero to Hunt, a website devoted to mentoring new hunters.