Home » Waterfowl Hunting » The Labrador Duck: A Tale of Modern Extinction

The Labrador Duck: A Tale of Modern Extinction

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada…

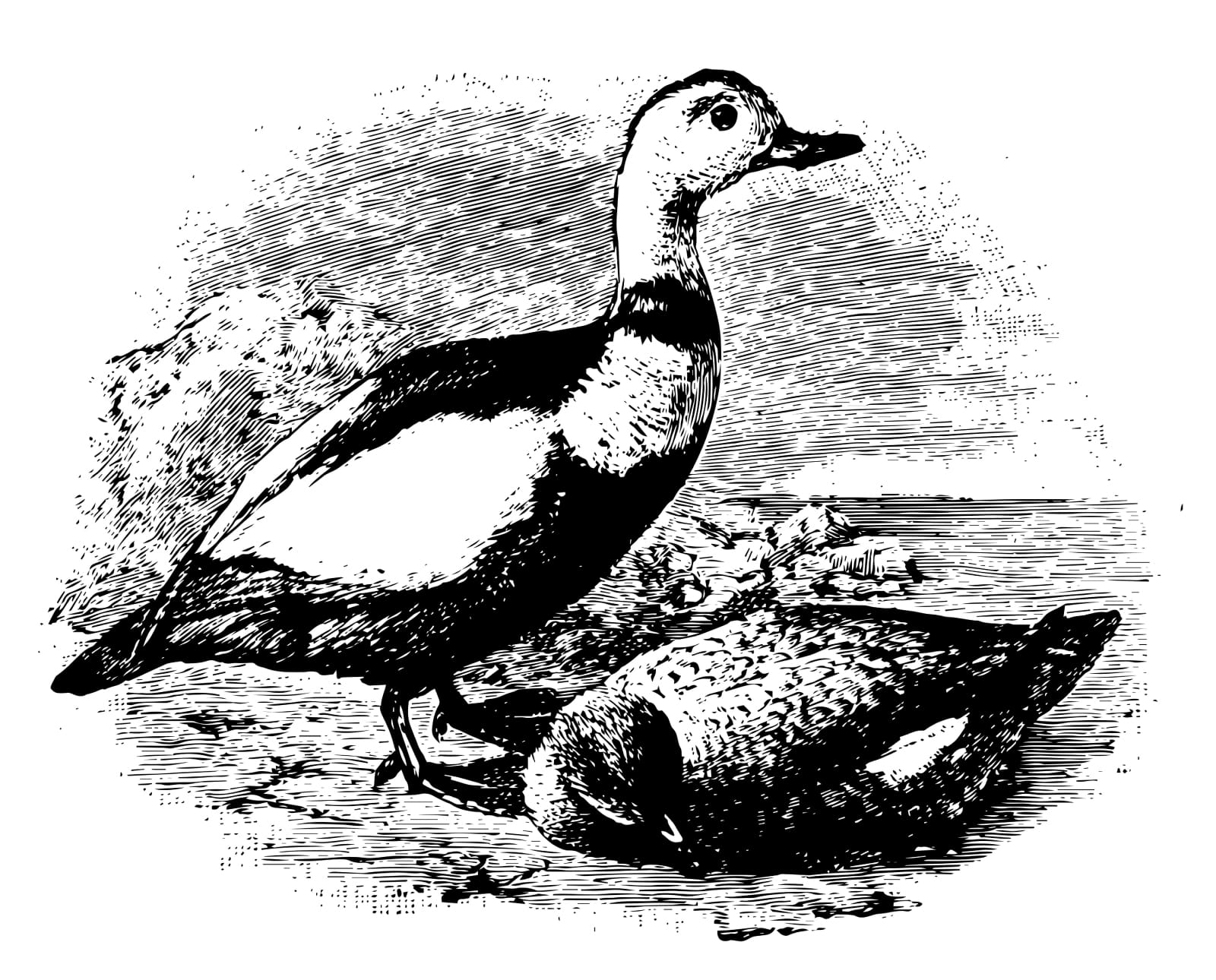

The Labrador Duck, an extinct black and white sea duck once found in North America, symbolizes the complexities of ecosystem interconnectivity and the challenges in historical wildlife research and misunderstood extinction causes.

The Labrador Duck was a beautiful black and white type of sea duck considered the first species of North American birds to go extinct during modern times. The last Labrador Duck to be hunted was shot in 1878 in Elmira, New York. It is presumed that the species went extinct shortly after.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

The loss of the Labrador duck is not your typical ecological warning about the dangers of over-harvesting, market hunting, or a general lack of conservation, but a reminder of the fragility and interconnectedness of our ecosystems to the flora and fauna that inhabit them.

One of the many challenges for biologists and historians when researching past hunting, harvesting, and taxidermy records of the Labrador duck is that it’s a species with many names. It’s an eider-type sea duck, also known as a pied duck, which includes the Golden Eye and Surf Scooter, leading to confusion about which historical entries are appropriate for which duck. Colloquially, it was also known as a skunk duck and the sand shoal duck due to its respective skunk-like black and white appearance and proclivity for sifting through sand bars near shallow estuaries.

Labrador Duck Habitat and Diet

The Labrador Duck was never considered a plentiful species, even before the arrival of European settlers. Alexander Wilson, a naturalist from the 1800s, stated that the Labrador Duck was a scarce and difficult-to-find species and was “never met with on fresh water lakes or rivers”.

As discussed in the ornithological journal The Auk, John Woodhouse Audubon, the son of the famous ornithologist John James Audubon, traveled to Canada with his father in 1833 in search of “northern sea ducks.” While exploring the region, he reported seeing nests belonging to what he thought were Labrador Ducks, “placed on the top of the low tangled fir-bushes.” Still, he was not able to find a living example to study.

A local boy later informed Audubon that the nests in question belonged to a “pied duck,” not a Labrador duck, leading to some confusion over whether the nests truly belonged to the elusive duck or if the term “pied” was used interchangeably to describe a variety of sea ducks. Despite the boy’s claims, Audubon was adamant that he had found what he sought.

When they were located, Labrador ducks were often found in bays, inlets, estuaries, sand bars, and other sheltered areas near shallow, sandy water. The Labrador duck was found in coastal areas, allowing for easy access to different kinds of mollusks, crustaceans, and shellfish, which comprised most of its diet. They would spend the warmer part of the year breeding in Canada near the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River, Quebec, and areas of coastal Labrador and migrated south to New England to avoid harsh Canadian winters.

Labrador Duck Appearance

The Labrador duck had a unique appearance. Males had a white belt on their breasts, black primary features, and dusky gray and brown feathers on the underside of the wing. Their flanks were a striking shade of black. One specimen was measured from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail at 20 inches with a wing span of 27 and a half inches.

As described by Canadian Naturalist Dr. A. Hall in the 1862 edition of The Canadian Naturalist and Quarterly Journal of Science, “…the outer scapulars colored with black, and the whole of the inner vanes of the inner half dusky, terminating in blackish, giving to the undersurface of the wing a dusky appearance; the primaries are all dusky black; the feathers on the cheek have a bristly feel; in other parts of the head and neck the feathers have a velvety feel, a good deal resembling that of the Great Northern Diver.”

One of the vulnerabilities exhibited by the Labrador duck was its highly specialized diet and unique bill, which had evolved to be particularly adept at finding food in sand and sediment. The Labrador Duck had a soft bill with a wide, flat tip that biologists theorized had evolved to help the birds probe for crustaceans and mollusks. Moreover, the duck’s bill had evolved to contain many lamellae, comb-like structures that act like a sieve or filter that helps the bird sift their food from unwanted material. This extreme specialization made the Labrador Duck very dependent on specific food sources, making it difficult for it to evolve or change feeding habits when their usual foods became scarce.

Hunting Labrador Ducks

Despite being illusive, rarely studied, and seldom seen, there are a few historical accounts of hunting the Labrador Duck, including some unique strategies employed to capture and harvest them. Known to be skittish and difficult to approach, they were said to take flight from the water at the slightest provocation or threat.

In 1891, Col. Nicholas Pike outlined his account of previously hunting the Labrador Duck:

I have in my life shot a number of these beautiful birds, though I have never met more than two or three at a time, and mostly single birds. The whole number I ever shot would not exceed a dozen, for they were never plentiful: I rarely met with them… They were shy and hard to approach, taking flight from the water at the least alarm, flying very rapidly. Their familiar haunts were the sandbars where the water was shoal enough for them to pursue their favorite food, small shellfish.

It may have been this seafood-based diet that led to the Labrador duck having a fishy taste and smell. Perhaps they were known colloquially as the skunk duck because of their characteristic black and white markings and their reputation for not tasting very good. Their poor reputation as table fare resulted in the Labrador duck being very cheap at most markets. The lack of edibility also reiterates that the Labrador duck’s extinction was not driven by market hunting but by a series of ecological issues that spelled the end for an animal dependent on specific habitats and food sources.

Andrew Wilson recalled seeing them in markets for purchase but in minimal numbers and with little popularity. “About forty or more years ago it was not unusual to see them in Fulton Market, and without doubt killed on Long Island; at one time I remember seeing six fine males, which hung in the market until spoiled for the want of a purchaser; they were not considered desirable for the table, and collectors had a sufficient number,” he said.

Col. Pike said, “I have only once met with this duck south of Massachusetts Bay. In 1858, one solitary male came to my battery in Great South Bay Long Island, near Quogue, and settled among my stools. I had a fair chance to hit him, but in my excitement to procure it, I missed it. This bird seems to have disappeared, for an old comrade, who has hunted in the same bay over 60 years, tells me he has not met with one for a long time…I would here remark, this duck has never been esteemed for the table, from its strong unsavory flesh.”

Shotgunning wasn’t the only tactic employed to kill Labrador ducks. Another interesting historical account described fishermen baiting their lines with mollusks and shellfish. The lines would then be cast into the water in the hopes of catching fish and feeding ducks.

The last account of hunting Labrador ducks comes from 1878. A tremendous storm hit the East Coast on December 12th, and a young boy from Elmira, New York, had the tenacity and gumption needed to brave the strong winter storm to procure some dinner for his family. Shotgun in hand, he huddled on the shores of the Chemung River in hopes of harvesting some ducks. Details are sparse on the contents of his game bag, but what is known is the teenager did shoot a very unique sea duck, a rarity that far inland.

Word began to spread quickly of the unique harvest and eventually reached the ears of an avid birder and conservationist named Dr. William H. Gregg, who raced to find the young hunter and his duck but was disappointed to arrive after it had been plucked and the majority of it eaten, leaving only the head and neck to be saved and studied. This specific bird would end up being the very last Labrador duck ever to be shot by a hunter and one of the last to be seen by humans before its declared extinction.

Eventual Extinction

The disappearance of the Labrador duck was a unique situation. Biologists hypothesize it was largely due to the animal’s specialized bill and diet, a rather rare position where market or unregulated hunting didn’t play a major role in the species’ demise. As mentioned extensively in historical accounts, the Labrador duck was not sought after for its meat. It tended to smell unappetizing and spoil quickly, making it unlikely that hunting made much of an impact on population numbers. Why hunt something that tastes awful and won’t sell when other, better-tasting birds are available?

Its unique bill made transitioning to alternative food sources difficult when the crustaceans and shellfish they relied on so heavily became scarce due to human development. As North America’s Atlantic coast became more industrialized, it may have impacted the shellfish and crustacean populations enough to decrease the Labrador duck population.

The Labrador duck was tightly connected to the local ecosystem, and when human development began to harm shellfish and mollusk populations, it created a ripple effect throughout the food chain. One ripple ultimately resulted in the extinction of the Labrador duck due to its inability to adapt to its quickly changing ecosystem. Naturalist Alexander Wilson commented on their disappearance, stating, “No one anticipated that they might become extinct, and if they have, the case thereof is a problem most desirable to solve, as it was surely not through man’s agency, as in the case of the Great Auk.”

In North America, the passenger pigeon, heath hen, and Carolina parakeet soon experienced extinctions largely linked to unregulated market hunting. The Labrador duck’s extinction highlights the fragility and interconnectedness of our ecosystems and the importance of even the smallest inhabitants.

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada who spends his free time hunting and fishing in Northern Ontario with his family and Wirehaired Pointing Griffon named Clover. Before becoming a teacher, Craig was a back country guide and grew up camping and fishing. When he’s not on an adventure with his young family or planning his next upland hunt, you’ll find him introducing his inner city students to the great outdoors.