Home » Partridge Species » Hungarian Partridge Hunting » Hungarian Partridge (Perdix perdix) – The Non-Native Gray Partridge

Hungarian Partridge (Perdix perdix) – The Non-Native Gray Partridge

- Climate Change Impact (Audubon) | +1.5°C - 34% Range Lost | +3.0°C - 56% Range Lost

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to…

An overview of the exotic Hungarian Partridge

As you would expect from its name, the Hungarian partridge is not native to the United States. Nevertheless, this bird is very popular for hunters in the northern plains. Also known as the gray partridge or simply “hun,” you can find a very healthy population in the north-central part of our country.

How Hungarian partridges were introduced to the United States

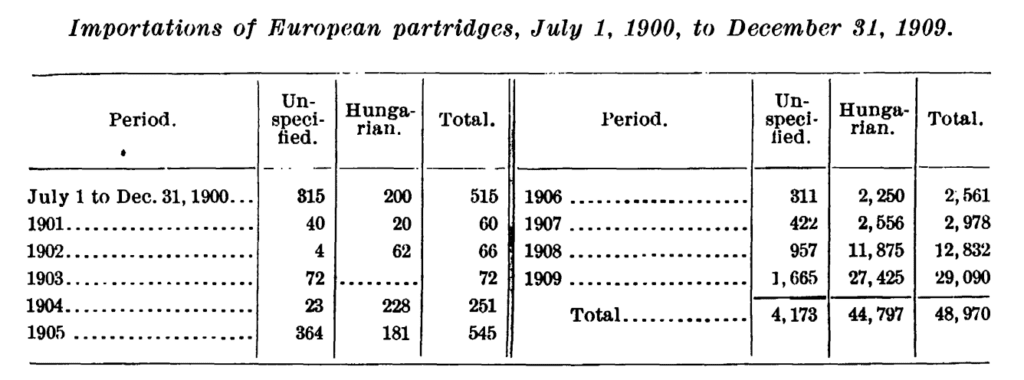

Henry Oldys was an assistant working with the US Biological Survey (a precursor to the US Fish and Wildlife Service) when he wrote the article “Introduction of the Hungarian Partridge into the United States.” In his article from 1909, Oldys writes, “Most of the partridges recently imported from Europe are known as Hungarian partridges. Other names have been applied to various consignments, such as English partridge, European partridge, Bohemian partridge, German partridge, and German quail. These birds, however, all belong to the one species, Perdix perdix, ordinarily known as the gray partridge, in contradistinction to the red-legged partridge (Gaccabis rufa) of southern Europe (sometimes called the French partridge).”

Oldys explains that before 1908, only 8,000 huns were imported into the United States. However, between 1908 and 1909, the US imported over 40,000 huns into the country. The uptick in hun importations was a result of decreasing native bird populations, and that attempts to introduce Italian partridge species to North America were unsuccessful. “The birds mated, built nests, and reared young, but practically all disappeared with the autumnal migration,” wrote Oldys. Upon learning that Hungarian partridges could survive North American winters, they were introduced to California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Washington. Oldys concludes his article by mentioning that introducing non-native species often fails, and wildlife managers should take caution when releasing new species into the wild. Oldys warns, “The possible effect on native game birds of the successful introduction of the partridge should also receive careful consideration… Hence it would seem wise to devote less energy and money to the establishment of this and other exotic species and give more attention to the restoration and maintenance of our native game birds.”

Description and life history of the Hungarian partridge

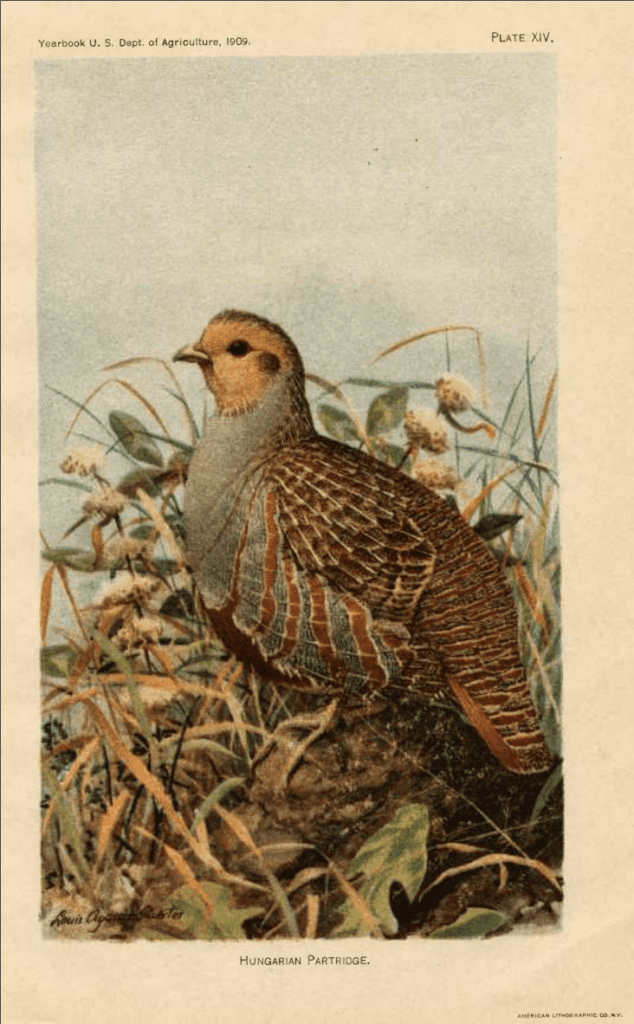

The Hungarian partridge is a medium-sized game bird with a short neck and tail. Like the chukar, both sexes look very similar in coloration and body size. While their bodies are mostly gray (hence their other common name, gray partridge), their faces are orange or cinnamon colored (All About Birds 2018). Their wings are gray with vertical orange stripes. Both males and females can have a dark brown U-shaped patch on their lower breast or stomach, but it is usually larger and more pronounced in males. Their central tail feathers are gray with cinnamon barring, but their outer tail feathers are solid cinnamon or reddish in color.

Males court females in late May to early June by standing upright to puff their chest feathers out and display their dark brown breast patch (National Audubon Society 2018; NatureServe 2018). They may also flick their tails up and down to attract attention. After mating, females scratch out a nest site on the ground, usually under a hedgerow or shelterbelt for cover. She then lines it with grasses and leaves before laying a clutch of 12 to 18 eggs (National Audubon Society 2018). The female will typically incubate the eggs by herself for about 23 to 25 days, yet both parents will tend to the hatched young (National Audubon Society 2018; NatureServe 2018). The chicks can feed themselves and make short flights in less than two weeks.

The hatched chicks usually remain with their parents as family groups until the following breeding season, and these groups may also join to form larger coveys throughout the winter. Chicks initially feed mostly on insects (e.g., grasshoppers, crickets), but will slowly transition to their adult diets throughout the year. Hungarian partridge adults forage on green leaves and grasses in the spring, and mostly on seeds from grasses (e.g., crabgrass, bluegrass, foxtail) and weeds or forbs (e.g., smartweeds, lamb’s quarters) in the fall (NatureServe 2018). Agricultural crops and waste grain are also popular forage, including cereal grains (e.g., wheat, oats, barley, rye), corn, and sunflower (National Audubon Society 2018).

Nest predators include raccoons, skunks, weasels, and opossums, while foxes, coyotes, and raptors (e.g., hawks, owls) also prey on adults and chicks.

Range and habitat of the Hungarian partridge

The Hungarian partridge was introduced from Europe and Eurasia across our country in the late 1700s. Populations were most successful throughout the northern prairie states, including Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Iowa, as well as southern Canada (National Audubon Society 2018). They were also introduced inWashington, Oregon, Idaho, Nebraska, Nevada, Wisconsin, and Illinois and still occur there in smaller numbers.

The Hungarian partridge requires relatively open fields to thrive. Grasslands, savannas, old fields, hay fields and crop fields are all prime habitat provided there are at least a few hedgerows, small woodlots and overgrown shrublands nearby for cover. While they will happily forage on waste grain in harvested crop fields, they will also use the grass and broadleaf weed species that often border these fields. Finding a few “huns” in wheat fields and even the leftover stubble is common.

Conservation issues for the Hungarian partridge

While the Hungarian partridge is not native to our country, it does have some conservation concerns here. It is estimated that the global breeding population is secure, numbering approximately 13 million birds (most of them occurring in Europe and Eurasia), yet only six percent live in the United States (All About Birds 2018; NatureServe 2018). The U.S. population has declined two to three percent per year since the 1960s, yet it is still locally common in certain areas. Predation, poorly timed spring rains, disease, accidents, and hunting all likely contribute to relatively high mortality rates.

Hunting opportunities for the Hungarian partridge

Since the Hungarian partridge overlaps its range with another non-native game bird, the ring-necked pheasant, you may be able to hunt both species at the same time. However, the partridge season generally opens well before the pheasant season, so by the time you can hunt pheasants, the remaining Hungarian partridge may be very spooky. If you would like to try hunting this exotic partridge species, here are a few states to start looking.

History: Wild Hungarian Partridge Hunting in New York

| State | Season | Season/Possession Limit |

| Idaho | September 15-January 31 | 24 birds |

| Illinois | November 4-January 15 | 6 birds |

| Iowa | October 14-January 31 | 16 birds |

| Minnesota | September 15-January 1 | 10 birds |

| Montana | September 1-January 1 | 24 birds |

| Nevada | October 14-February 4 | 18 birds |

| North Dakota | September 9-January 7 | 12 birds |

| Oregon | October 7-January 31 | 24 birds |

| South Dakota | September 15-January 6 | 15 birds |

| Washington | October 7-January 15 | 18 birds |

| Wisconsin | October 14-December 31 | 9 birds |

| Wyoming | September 15-January 31 | 15 birds |

As with all upland bird hunting, having a good hunting dog on your side will definitely help you find more birds. Hungarian partridge tend to hold fairly well for dogs, so a pointing breed can be your secret weapon. Let them work out in front of you along a transition zone (e.g., where a crop field meets grass habitat) and do not be discouraged if you have to walk several miles per hunt. When you do flush a bird, the rest of the covey is likely to flush with it, so be ready for some fast shots. Because the Hungarian partridge inhabits some wide open spaces and holds fairly tight, a dog-less hunter will likely have to walk triple the miles (or more) to flush enough birds to rival a hunter with a dog. Nevertheless, if you just want to get out walking in some beautiful scenery with the potential to harvest a “hun” (along with other game birds), hunting the Hungarian partridge can be a very addicting hobby.

Sources:

All About Birds. 2018. Gray Partridge. Accessed at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Gray_Partridge/lifehistory

National Audubon Society. 2018. Guide to North American Birds. Accessed at: http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/gray-partridge

NatureServe. 2018. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. Accessed at http://explorer.natureserve.org

Oldys, Henry. No date. “INTRODUCTION OF THE HUNGARIAN PARTRIDGE INTO THE UNITED STATES.” The U.S. Biological Survey. Accessed at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/37902

Ryan Lisson is a biologist and regular content contributor to several outdoor manufacturers, hunting shows, publications, and blogs. He is an avid small game, turkey, and whitetail hunter from northern Minnesota and loves managing habitat almost as much as hunting. Ryan is also passionate about helping other adults experience the outdoors for their first time, which spurred him to launch Zero to Hunt, a website devoted to mentoring new hunters.

As a boy growing up on a dairy farm in South Dakota during 70s $ 80s I was fascinated with Gray partridge, we had nice size coveys on each of the 3 quarters farmed. Due to modern row crop farming, pesticides, and lack of habitat they are gone. I haven’t seen a pair in 10 years. Loss of wildlife, drainage of wetlands, water quality, soil erosion, and exasperated flooding can all be attributed to row crop farmers, and it’s only getting worse. Nobody cares. How depressing.