Home » Turkey Hunting » Wild Turkeys in Ontario: Conservation History, Reintroduction, and Hunting

Wild Turkeys in Ontario: Conservation History, Reintroduction, and Hunting

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada…

After being extirpated from the province, reintroduced turkeys have created a stable, huntable population in Ontario

Snow begins to melt in many parts of Ontario, Canada, each April. Ontario’s fields and forests have become the setting for an all too familiar sight: tom turkeys establishing their dominance through bouts of combat, winter flocks splitting apart, and, best of all, the early mornings are filled with a cacophony of gobbles and yelps. However, it wasn’t long ago when those iconic and endearing sounds of spring were all but silent in Ontario.

Historically, European settlers hunted Ontario’s eastern wild turkeys to extinction due to unregulated private and market hunting. The last native Ontario turkey died at the turn of the 20th century. Almost 75 years later, a group led by the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) and partners like the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters began one of the world’s most successful wildlife reintroduction programs. Today, the province boasts approximately 70,000 to 100,000 eastern wild turkeys, fall and spring hunting seasons, and a growing list of huntable populations.

Origins and Decline of Ontario’s Wild Turkey

Ontario is home to just one type of wild turkey: the eastern (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris). Ontario is in the northernmost edge of the eastern wild turkey’s range. The earliest recorded sighting of a wild turkey in Ontario was in 1624 by Gabriel Sagard, a Recollect priest who reported seeing them in central Ontario near Georgian Bay. In the late 1700s, the wild turkeys were so prolific in central and southern Ontario that early European settlers considered them pests. The turkeys frequently pillaged crop fields to the point where bounties were occasionally paid to reduce turkey numbers in problematic areas.

Zoologist L.L. Snider with the Royal Ontario Museum confirmed that turkeys were considered “common” in Ontario until the 1880s when European settlements expanded, resulting in a loss of habitat as farms replaced forests. Coupled with live trapping for sale in markets and unregulated private hunting, Ontario’s native turkey population was decimated. Live-trapping turkeys was “rampant” and led to the province enacting one of its first conservation laws that outlawed the practice in the hopes of curbing declining turkey numbers. Unfortunately, market hunters kept doing it even with the illegalization of live trapping. Within less than 100 years, Ontario’s eastern wild turkeys were locally extinct. The last native turkey to be seen alive in the province was in 1909 near Aurora, 30 miles north of Toronto.

Reintroducing Wild Turkeys to Ontario, Canada

Biologists’ early reintroduction efforts used hatchery programs. Pen-raised wild turkeys would eventually be released into the wild as adults. This was promptly shown to be a horrible strategy for reintroduction purposes but fantastic for feeding local predators. Once turkeys hatch from their eggs, they imprint on the first thing they see, which should be their mother. However, when turkeys are born in hatcheries, they often imprint on people. This quickly leads to confused birds that, once released, were susceptible to hazards like vehicles or eager predators.

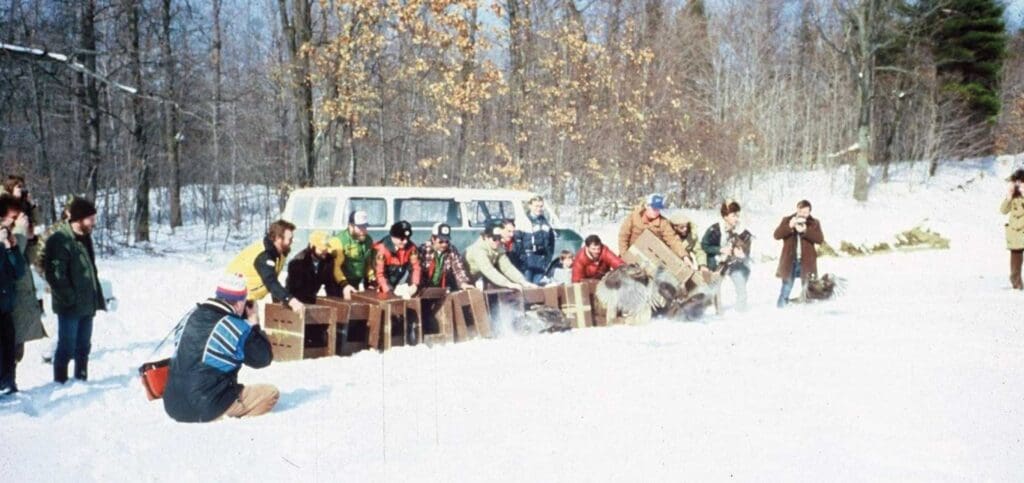

With the invention of net cannons, a rocket-like device that sends out a net capable of containing large groups of turkeys at a time, the possibility for successful reintroductions skyrocketed. With the advent of this new technology, biologists and conservationists could capture groups of turkeys from different locations. Then, they moved these captured turkeys to new locations with a more diverse turkey gene pool within their populations. That diverse genetic make-up provided heartier stock less susceptible to disease and inbreeding.

After successfully using net cannons in the United States, Ontario recognized the potential for success. In the 1970s, the province launched its own wild turkey reintroduction program, this time with live-trapped wild birds. The province’s Ministry of Natural Resources and its partners invited renowned wild turkey specialist James Pack from West Virginia to assess the situation and identify different areas with suitable habitat. By 1983, Ontario made agreements with several U.S. states to exchange different species for aiding each other’s respective wildlife reintroduction programs.

Ontario traded river otters to Missouri, moose to Michigan, and partridges to New York, in exchange for 74 eastern wild turkeys that would later be released in Southern Ontario, near Kingston. Later exchanges with Missouri, Iowa, Michigan, New York, Vermont, New Jersey, and Tennessee would bring the total to around 274 live trapped and relocated birds. The reintroduction program cost $120,000 Canadian dollars, of which only $20,000 came from the government. The remaining $100,000 was donated by conservation groups like the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters and the National Wild Turkey Federation.

Eventually, the program’s success became self-sustaining. The MNR could begin to trap and transport turkeys from different areas of the province and relocate them to areas of need. Between 1985 and 2005, 4,400 wild turkeys were trapped and relocated to 275 different locations throughout the province. According to the MNR and the Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas, Ontario’s wild turkeys population is robust and wide-ranging, with populations as far north as Lake Nipissing and throughout most of the central and southern parts of the province. The MNR published the most recent estimate of Ontario’s wild turkey population size in 2007 at 70,000 birds. However, this number is a rough estimate based on annual harvest numbers and extrapolations from annual harvest reports. Some wildlife biologists have questioned the validity of that figure. The estimate tends to range by plus or minus 20,000 birds, depending on the source and their assessment method.

Factors Inhibiting Wild Turkey Population Growth in Ontario, Canada

Since hunters and conservationists have recognized the critical importance of selective harvests, quotas, and hunter reporting, the population of wild turkeys has responded by growing exponentially. However, factors still impact the success and proliferation of turkeys in Ontario.

Until recently, some biologists were concerned about pathogens like West Nile Virus impacting wild turkey populations. They worried that game birds might be susceptible to infection and other related symptoms. Additionally, there were wonderings of whether or not hunters who eat their harvest could get sick and if wild turkeys could be a potential vector for animal-to-human disease transmission. Fortunately, a recent study by Dr. Amanda McDonald at the University of Guelph, who studies pathogens in wild turkeys, found that “Wild turkeys don’t seem really susceptible to developing disease from West Nile infection, but they do get infected.” Her study, coupled with one from the US, showed that many birds seem to be infected by the virus but don’t develop the disease or suffer any ill effects from its symptoms. West Nile Virus doesn’t seem to have any noticeable impacts on turkey mortality.

Ph.D. candidate Jennifer Baici, who is studying Ontario’s wild turkeys at Trent University, reports that one of the most significant factors in limiting Ontario’s wild turkey’s expansion into the northern parts of the province is related to snow depth and cold temperatures. Biologist Matthew Gonnerman and others have shown that all wild turkeys are significantly impacted by deep, powdery snow, which restricts their ability to move across the landscape to forage and evade predation. There has even been a reported case of a wild turkey freezing to death in northern Ontario due to frostbite, supporting the notion that the winter conditions often result in a higher mortality rate than during warmer seasons.

Baici noted, “We found that the strongest predictors of turkey presence were building density and snow depth/temperature.” She hypothesized that the relationship between turkey presence and building density comes from turkeys’ abilities to adapt to changing landscapes and locate alternative food sources, such as bird feeders or leftover farm grains. In the future, changing climates and warmer weather could decrease the snow load in the northern parts of the province, eventually leading to an expanded wild turkey range.

The Future of Ontario Turkeys and Turkey Hunting

Ontario’s first turkey hunting season opened in the spring of 1987 in just two Wildlife Management Units located in the southeastern portion of the province. Twenty-six years later, Ontario boasts spring turkey hunting seasons in 90 Wildlife Management Units. Fifty-four of those same units also have populations high enough to support a fall hunting season.

Initially, the Ministry of Natural Resources required all hunters to participate in a mandatory turkey hunting education course that reinforced safety measures, tactics, and proper identification of male and female birds. Today, that turkey component is incorporated into the general hunter education course required for all Ontario hunters.

Ontario’s Turkey Management Plan outlines guidelines that aim to harvest approximately 30 percent of the male population through spring seasons which begin on April 25th and go until the end of May. Through this management plan, the Ministry of Natural Resources determines whether or not an area can be opened to hunting based on whether or not the site has at least an estimated 200 birds. Hunter reports and scientific observations determine this number. The spring turkey hunt season consists of bearded birds only. In the fall, hunters can harvest either a male or female turkey.

Fall seasons are determined by similar guidelines set forth by the Ministry. They include having a spring harvest of at least 200 birds in the three preceding seasons. Alternatively, a fall season can be opened if the harvest density within that Wildlife Management Unit is equal to or greater than 0.4 turkeys per square kilometer of turkey habitat. This reinforces the importance of hunters reporting their harvests accurately and related sightings because they are used to determine future hunting opportunities within the province.

The Ministry of Natural Resources reports that the number of jakes harvested each season varies based on the success rate of the previous year’s hatch. Still, the age structure of harvested male birds has remained relatively stable in recent years. After studying Ontario’s Wild Turkeys for her Ph.D., Jennifer Baici reports, “We don’t have any evidence to lead us to believe that Ontario’s turkey populations are in trouble… We likely have fewer turkeys than were estimated in the 2007 management plan. However, this is likely a reflection of the accuracy of the 2007 estimate rather than the dynamics of the population. Ontario’s turkeys seem to be doing just fine for now.”

Wild turkey populations look healthy and stable and should continue to increase in number due to strong conservation efforts and support from organizations like the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters and the Canadian Wild Turkey Federation. In the future, that stable growth should translate into additional spring and fall hunting opportunities within the province of Ontario.

For more information about turkey hunting in the Province of Ontario, contact the Ministry of Natural Resources at www.Ontario.ca

Craig Mitchell is an Outdoor Education Teacher from Toronto, Canada who spends his free time hunting and fishing in Northern Ontario with his family and Wirehaired Pointing Griffon named Clover. Before becoming a teacher, Craig was a back country guide and grew up camping and fishing. When he’s not on an adventure with his young family or planning his next upland hunt, you’ll find him introducing his inner city students to the great outdoors.

Great article, I live in Southern Ontario and love seeing and hearing turkey in the area. However, I believe that the first release site in 1984 was in the Long Point area, not Kingston. There is a monument to it in the Backus Woods area, I can’t remember the exact address but have driven past it while hunting in the area.

Hi Tom, thanks so much for your comment. I’ll have to check that out, I know there were a few initial relocations sites but I’d still like to be as accurate as possible.

– Craig

I found the site again yesterday while turkey hunting in the area. You have to go to the Backus Woods South Parking lot on 3rd Concession Road near Port Rowan. There is a trail that runs back from there to the release site, where they have put up a stone cairn to commemorate the site.