Home » Hunting Dogs » The Word “Setter” Does Not Mean What We Think It Does

The Word “Setter” Does Not Mean What We Think It Does

- This story was originally published in Volume 3, Issue 2 of Project Upland Magazine.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

The truth behind the word ‘setter’ has quite the history behind it; one you may not have expected

The Setter is the handsomest and perhaps the most generous of the canine race; but by what peculiar cross he originated, is not well known; and all conjectures on this head, though very interesting to the sportsman, are too much involved in uncertainty, to be much depended on.

— T.B. Johnson

Listen to more articles on Apple | Spotify

While people will always disagree about which breed is the “handsomest and perhaps the most generous,” everyone agrees that trying to follow all the twists and turns of the setter’s creation story is more or less impossible. But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn something more about them by taking a look at some of the more interesting, and even surprising, stops along the way.

In 1872, Edward Lavarack, the father of the modern English setter answered the question by writing “… the setter is nothing more than the setting spaniel improved.” Ok, so setters are spaniels that, at some point were “improved” to become setters. But what exactly is a setting spaniel, and what exactly were the “improvements” that turned them into setters?

Historical accounts of setting spaniels

One way to get to the bottom of it is to look at the words Lavarack used: spaniel, setting, and setter.

Let’s start with “spaniel.” The most common view is that it means “from Spain.” Gaston Febus himself wrote that: “There is another type of dog that we call chiens d’oysel and espaignolz (spaniels), because this type comes from Spain, even though there are some in other countries.”

But did spaniels really come from Spain? Jean Castaing didn’t think so. He believed that épagneul-type dogs probably developed somewhere further north where a colder, wetter climate would have favored long-haired dogs and presented a fairly good argument that spaniel came from an old French word ‘espanir’ which means to “spread out.”

And Febus may have said they came from Spain as a kind of insult. He wrote that espaignolz (spaniels) were good for certain kinds of hunting but they were loud and bothersome, just like his wife’s Spanish family. So, calling them spaniels may have been his way of dissing the in-laws. In any case, everyone agrees that spaniels were fast, busy, medium-sized dogs that excelled at flushing game. From wherever they were first developed, they eventually spread across much of Europe and, at some point, crossed the English Channel.

The first use of the word spaniel in English is probably in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Wife of Bath story that features a licentious woman who “…hankers for every man that she may see; For like a spaynell will she leap on him”. The Duke of York also mentions spaniels around the same time in The Master of Game, a translation and adaptation of Le Livre de la Chasse. In Chapter 17, the Duke translates, almost word for word, Gaston Febus’s description of spaniels: “…commonly they go before their master, running and wagging their tail, and raise or start fowl and wild beasts. But their right craft is of the partridge and of the quail. It is a good thing to a man that has a noble goshawk or a tiercel or a sparrow hawk for partridge, to have such hounds.”

As to their appearance, the Duke provided another word-for-word translation of Febus, with one glaring error. He wrote: “a fair hound for the hawk” should have a great head, a great body, and be of fair hue, white or tawny.”

The error is the word “tawny,” which means a yellowish-brown or orange-brown coat. In the French original, Febus did not use the word tawny (fauve in French) he wrote that the coat was tavelé, which means “spotted” or “ticked,” just like the coats of modern flushing spaniels and setters.

The most important line in the Duke’s description is the following: “And also when they be taught to be couchers they be good to take partridges and quail with a net.”

There are two very important things in it that we must keep in mind as we dig deeper into the setter’s origin story. The first is the word “coucher.” It comes from the Middle English word “couch” which means to lie down. The other is that, at the time, spaniels had to be trained to couch.

The next time we come across the word Spaniel in a major work is in 1570, in the book De Canibus Britannicis written by Johannes Caius (Dr. John Kays). It is unclear how much personal experience Caius had with dogs or even if he had any particular interest in them, but he must have known the right people in the right places because his work is remarkably accurate and provides an in-depth look at the many kinds of dogs in Britain at the time. The only problem for modern readers is that it is written almost entirely in Latin. Fortunately, six years after its release, Abraham Fleming published Of Englishe Dogges, not a word-for-word translation of Caius’s book but more of an interpretation. From Fleming, we learn what spaniels looked like, and where some of them came from (spelling modernized): “The most part of their skins are white, and if they are marked with any spots, they are commonly red, and somewhat great therewithal, the hairs not growing in such thickness but that the mixture of them may easily be perceived. Others of them be reddish and blackish, but of that sort there be but a very few. There is also at this day among us a new kind of dog brought out of France (for we Englishmen are marvelous greedy gaping gluttons after novelties, and courteous cormorants of things that be seldom, rare, straunge, and hard to get.) And they be speckled all over with white and black, which mingled colours incline to a marble blue, which befits their skins and affords a seemly show of comlynesse. These are called French dogs as is above declared already.”

We also learn that there were two major types of spaniels—”The first findeth game on the land. The other findeth game on the water”—and that the ones that worked on land were further divided into two sorts, one for hawking, and one for netting. The main difference between the land spaniels was their hunting style. Spaniels used for hawking searched for and flushed game, or in Fleming’s words they “… play their parts, either by swiftness of foot, or by often questing, to search out and to spring the bird for further hope of advantage.” He also says that they were “denominated (named) after the bird which by natural appointment he is allotted to take.” So, there were pheasant spaniels, partridge spaniels, and spaniels for the falcon. Today, we still name one spaniel, the Cocker, after the bird it hunts, the woodcock.

The other sort of spaniel did not flush birds, but showed the hunter where the birds were hiding, or in Fleming’s words, “by some secret sign and privy token betray the place where they fall.” And unlike hawking spaniels which had a reputation of being noisy and hard to handle, spaniels used for netting were considered easier to train, and they work in silence, making “… no noise either with foot or with tongue while they follow(ed) the game. These attend diligently upon their Master and frame their conditions to such beckes, motions, and gestures, as it shall please him to exhibit and make, either going forward, drawing backward, inclining to the right hand, or yielding toward the left…”

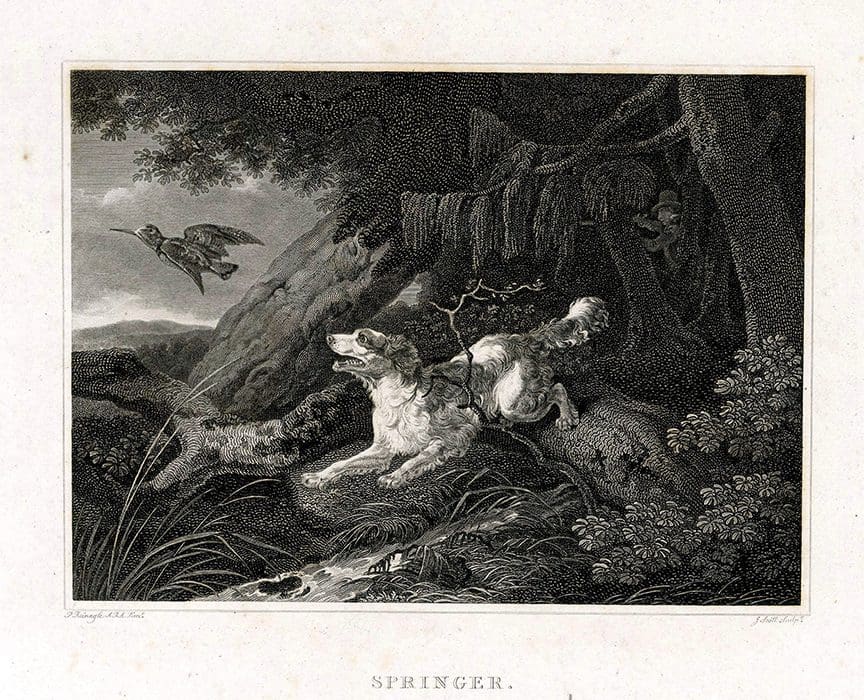

This part of Fleming’s work, inspired by the Caius book, was an updated and expanded description of the dogs the Duke of York called couchers. But neither Caius nor Fleming adopted the word coucher from the Duke’s book. If they had done so, today we’d have English, Irish, and Gordon Couchers. Instead, Caius chose a different name for those dogs. In a schematic he drew up to categorize the various types of dogs in Britain at the time, he listed them as Setters.

Fleming then explained that “…this kind of dog is called Index, Setter, being indeed a name most consonant and agreeable to his quality.”

So according to both Caius and Fleming a “setter” was a dog that “betrays the place of the bird’s last abode.” And since setter sounds like sitter, and setting sounds like sitting, it has long been assumed that, like the name coucher, the name refers to dogs that lay down. But it is a mistake. For Caius and Fleming, the word “setter” had nothing to do with laying down, and to understand what they truly meant we have to go back to the original Latin text and then take a close look at Fleming’s English translation.

Understanding historical translations of ‘Setter’

Caius wrote his book in Latin because that was the language 16th-century scholars used to communicate with each other, no matter where they were or what their mother-tongue may have been. But he did include a few English words in the text, specifically the names people gave to the types of dogs in their Britain. That is why words like Tumber, Dancer, Turn-spit, Spaniel, and Setter appear in the schematic he provided.

And since Caius knew that many of his readers didn’t read or speak English, he also included a sort of glossary at the end of his book with definitions of the English words he used. Here is what he wrote about the word setter: “… Setter nominare solent, a verbo sette, quod locum designare nostris Britannis significat.”

Not particularly helpful if you don’t read Latin. Fortunately, Fleming gave us a translation, sort of.

“Setter (comes from the) word Set which signifies in English that which speakers of Latin mean by the words ‘Locum designare.'”

So Fleming translates most of the definition, except the most important part—he didn’t explain what Locum designare means. And by doing so, he created a sort of linguistic trap that we’ve been falling into for nearly 500 years. If he had actually translated the entire sentence and written that ‘Locum designare’ means, “to designate a location,” generations of authors and experts would have known that the word setter had nothing to do with sitting, couching, or lying down. It referred to the dog showing the hunter where the game is. The fact they were trained to lay down while performing the act is irrelevant—a dog can designate a location while standing up, sitting down, or lying flat on its belly. Setter refers to a dog that designates or indicates the location of game, or in Caius’ words, one that “betray(s) the place of the bird’s last abode.”

But the other name Fleming mentions—“…this kind of dog is called Index.”—what did he and Caius mean by that? In the 16th century, the index was the name of a part of a sundial that casts a shadow to indicate the hour. Nowadays, we don’t use sundials much, but they still exist, and they still have a part that casts a shadow to indicate the time of day. The only difference is that we don’t call that part an index anymore; we call it a pointer.

For Caius and Fleming, the words index and setter were synonymous. They both meant “to point at something.” Yet to this day, many people believe that the word “Setter” refers to a dog that “sets” or “sits” down. But it is a mistake. Setter actually means pointer with a lowercase “p and it is a name “most consonant and agreeable to his quality.”

So, if there was already a difference between flushing spaniels and setting spaniels when Caius wrote his book, how much of it was due to training and how much was natural? The most likely answer is a bit of both.

Unraveling the Setter’s origin

Obviously, the amount of instruction required to teach a busy spaniel to be a coucher varied among individuals. But throughout the early literature, there are references to natural inherited qualities possessed by the various sorts of hunting dogs.

Fleming wrote that spaniels “naturally love to hunt the wing of any bird whatsoever” and Nicolas Cox said they were “naturally addicted to the hunting of feathers.” Clearly, the men who were breeding and training dogs at the time understood the difference between natural and trained behaviors. And since all dogs, indeed all canines, have at least some tendency to pause before they pounce, if you wanted to train dogs to couch you would favor dogs with pronounced pause-before-the-pounce behaviors. Indeed, some dogs probably needed no training at all. Even Caius mentions dogs that would “…stayeth (their) steps and…proceed no further..” and the 17th-century painting by Oudry and Desportes, commissioned by the King of France, clearly depict long-haired dogs in natural pointing postures. So it is reasonable to assume that “improved” spaniels—fast, wide-ranging dogs with a strong natural point—were already in use on the continent in the 1500s or even earlier. As for their arrival in England, we have at least one record of importation that gives us a very specific date. In the Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series of the Reign of James I, we find the following entry for Jan. 17, 1624.

“A French Baron, a good falconer, has brought him 16 cast of hawks from the French King, with horses and setting dogs; he made a splendid entry with his train by torch – light, and will stay till he has instructed some of our people in his kind of falconry, though he costs His Majesty 25£ or 30£ a day.”

The French King at the time was Louis XIII, a man obsessed with hunting in all its forms. The kind of hawking the French Baron was sent to teach in England was probably a new variation of the “waiting on” flight. In medieval times, it consisted of trained birds of prey flying above a hunting party as it galloped across fields with dogs running ahead of them flushing ducks, hare, partridges, or any other sort of game fit for a falcon. The new development was adding setting dogs to the mix which gave breeders one more reason to favor dogs with strong natural tendencies to point.

“Game hawking with pointing dogs and falcons trained to ‘wait on’ crystalizes the epitome of falconry, now game birds can be found, pointed, the falcon released to fly high above the point, and then, when the stage is set, the game can be sprung. The result is the total distillation of the flight, once so unpredictable, now so singularly stage-managed with that dowards stoop by the falcon onto its prey taking place directly in front of the spectators!”— Derry Argue p. 32.

In addition to trying to unravel the mystery of the Setter’s origins, much has been written about how it was “improved” or what Edward Laverack referred to as attaining its “sufficiency of point.” Some have suggested that the pointing instinct in setters came from the Pointer. Laverack disagreed.

“How the setter attained his sufficiency of point is difficult to account for, and which I leave to wiser heads than mine to determine. The setter is said, and acknowledged by authorities of long-standing, to be of greater antiquity than the pointer; if this is the case, and which I believe it to be, the setter cannot at first have been crossed with the pointer to render him what he is.” — Laverack, The Setter

Laverack is correct, sort of; the Setter is of “greater antiquity” than the Pointer in England. But on the continent, setters and pointers evolved more or less contemporaneously, and there was surely at least some cross-breeding between long-haired and short-haired pointing dogs in various parts of Europe. Laverack also overlooks the fact that, until the mid-1700s, the amount of natural pointing instinct among setters varied considerably. Indeed, even well into the 20th century, some lines of setters—especially Irish Setters—were sometimes criticized for lacking sufficient amounts of point. Yet, when Laverack started breeding setters in the mid-1800s the vast majority of setters were strong, natural pointers. In any case, it is reasonable to assume that when short-haired pointing dogs from Spain and France arrived in England, about a century after setters first appeared, breeders probably did crossbreed on occasion and ended up strengthening any pointing instincts that were already in their lines of setters. Rawdon Lee offered his thoughts on the issue, quoting Mr. William Lort, a renowned setter expert of the time:

“…I am quite sure that years ago, say from forty to fifty (early 1800s), it was not an uncommon thing to get a dip of Pointer blood into the best kennels of Setters. W. Talpin wrote in the Sportsman’s Cabinet that the setter was ‘…a species of Pointer originally produced by a commixture between the Spanish Pointer and the larger breed of English Spaniel.'”

But Lee also made sure to take these assertions with a grain of salt “(it) will always be a matter of discussion between persons interested in the breed, as many are to be found who deny the existence of the Pointer cross.”

Another piece of evidence of cross-breeding may be the fact that within a decade or two after the first imports of short-haired pointing dogs, setters started to point standing up, like a pointer, instead of crouching as they had always had before. Vero Shaw suggests that the change came about after hunters switched from netting birds to shooting them on the wing.

“It is, of course, perfectly well known that the modern Setter usually points his game standing up, as a Pointer does, and the abandonment of netting is unquestionably responsible for this alteration in the method of a Setter carrying out his work. Before, when the sportsman was anxious to net as many birds as he could, it was most essential that they should be as undisturbed as possible, and the presence of a dog would, of course, increase the chances of their being frightened away before the net was fixed for their capture. The chances of the dog being seen by the game were naturally lessened when he lay down, and this, no doubt, was the reason for his being broken to do so.

“Now things are much altered, and the sportsman only wants the whereabouts of the game to be indicated, so that he may walk them up. There is, however, a perfectly palpable tendency to crouch still observable in many of the best and highest bred Setters of the present day, which is unquestionably accounted for by the former habits of the breed, and the uses to which it was put.” — Vero Shaw, Illustrated Book of the Dog.

But seeing such a widespread change in such a short period also suggests that a drop or two of pointer blood crept into setter lines. Indeed, the “alteration in the method of a Setter carrying out his work” continued throughout the 18th century, and by the late 1800s setters could even be penalized for laying down on point in field trials.

“… In the present day, as a rule, the standing position is preferred, though some well-known breakers, and notably George Thomas, Mr. Statter’s keeper, have preferred the ‘drop,’ which certainly enables a fast dog to stop himself more quickly than he could do by standing up. It is, however, attended with the disadvantage that in heather or clover a ‘dropped’ dog cannot be seen nearly so far as if he was standing, and on one occasion, at the Bala Trials of 1873, the celebrated Ranger was lost for many minutes, having ‘dropped’ on game in a slight hollow, surrounded by heather.

“As a rule, therefore, the standing position is the better one, but in such fast dogs as Ranger and Drake, ‘dropping’ may be excused. At the above meeting, however, after a long and evenly balanced trial between Mr. Macdona’s Ranger and Mr. R. J. LI. Price’s Belle, the latter only won by her superior attitude on the point, and Ranger again suffered the penalty for dropping at Ipswich in 1873.”

Idestone thought that “falling to game” was an artificial behavior, but he did not object to it.

“There are also fashions as to the Setter’s work. Originally, he was taught to fall to his game, as he was used either for hawking birds, or to cover them (dog and all) with a net. He was induced from imitation—being broken with the old Spanish Pointer, which never fell to game—to stand like his fellow pupil, for falling is an artificial attitude. Terriers, Spaniels, Retrievers, even cats, stand before they pounce; so do lions, tigers, or leopards, especially the cheetah. Standing is bracing the nerves and balancing the body for a spring.

“Latterly the old Setter instinct of dropping has shown itself in a marked manner, and many of the very best Setters fall as if struck by lightning. I never object to it in the Setter. To my mind it is a sign of breeding; but it is disadvantageous on heath, moorland, or amongst high scrub or deep cover of any kind, especially if the dog is of a dark colour, as he is completely hidden, not only from his owner but from the other dog, who may blunder up the game, or be led from getting once or twice close to the point when he ought to back, to neglect this essential part of his training.”

Today, in North America, any tendency to crouch or lay down on point is severely penalized in most field trial formats and anything but an upright, lofty point is generally frowned upon by the majority of American hunters. In Italy, on the other hand, breeders specifically select for the crouching posture because field trial judges and hunters prefer dogs that demonstrate an extreme panther-stalking-its-prey crouching style. It may seem like a small difference, but it is indicative of one of the challenges faced by all the setter breeds today.

Officially, there are only four, the English, Gordon, Irish Red, and Irish Red and White. But since they’ve all been “distributed beyond the limits of their respective districts” and bred around the world for different game, terrain, and purposes there are now different types, subtypes, and strains within each breed, not to mention the irreparable split between field-bred and show-bred lines. So even if a hunter seeking a pup narrows his or her choice down to one of the four recognized breeds, they still have a lot of homework to do if they want to find the perfect fit.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

Did I miss the difference between what “setting” and “pointing” is?