From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

Explore the history and story of a curious dog breed that never was.

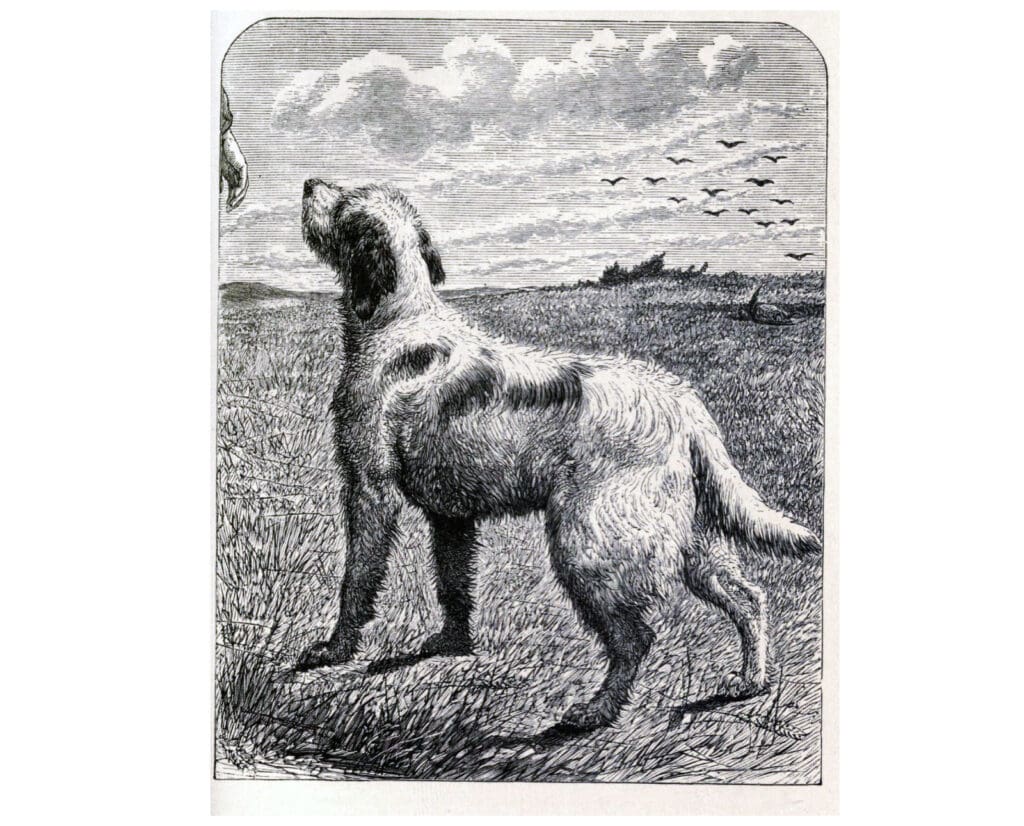

Sprinkled here and there throughout the sporting literature of the 19th century are references to Russian Setters. Despite the references and the fact that there were a number of dogs listed as Russian Setters entered into studbooks in England and the U.S., such a dog breed never actually existed. Be that as it may, for a while, sportsmen did breed and hunt over dogs that they called Russian Setters. From writings of the time, we can form a fairly clear picture of what those dogs were like.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

In terms of appearance, everyone agrees that dogs called Russian Setters had long, rough coats and facial furnishings. Edward Laverack once said that he once saw “a magnificent type of the Russian Setter buried in a coat of a very long floss silky texture; indeed he had by far the greatest profusion of coat of any dog I ever saw.”

When Vero Shaw wrote to William Lort asking him to describe the appearance of the Russian Setter, Lort replied:

Roughly speaking, in appearance this dog is rather like a big “warm” Bedlington Terrier. There are two varieties of the breed, and curiously enough they are distinguished from each other by the difference in their color. The dark-colored ones are deep liver and are curly-coated. The light-colored ones are fawn, with sometimes white toes and white on the chest; sometimes the white extends to a collar on the neck. These latter are straight-coated, not curly like the dark ones. My recollection of this breed extends back some fifty years, and the last specimen I owned of it—a light-colored one—I gave away to a friend who would not take a hundred pounds for it.

When it came to the Russian Setter’s field prowess, there was no agreement. Some considered the breed to be as good or even better than the other setters of the time. Others thought they were hard-headed boot-lickers. Laverack wrote that a friend of his, a Mr. Arnold of London, had two Russian Setters, purchased as pups and professionally trained that “…were not at all good specimens of the class, and, as working dogs, comparatively useless. So disgusted was he with them before he left, that he shot one, and gave the other away.”

Another friend of Laverack described Russian Setters as

. . .good but most determined, willful, and obstinate dogs, requiring an immense deal of breaking, and only kept in order and subjection by a large quantity of work and whip; not particularly amiable in temper, but very high-couraged. . .“Old Calabar” got a brace of these puppies, had them well broken, and took them to France; but, after shooting to them two seasons, and being disgusted with their wilfulness and savage dispositions (they would take no whip), sold them to a French nobleman for a thousand francs and considered he had got well out of them.

Despite a lot of criticism from some quarters, most accounts of hunting over Russian Setters portray them in a positive, even glowing, light. Here is one such account by Fredrick Tolfrey, published as “Dogs and Dog Days” in Sporting Magazine in 1845.

Strange to say, though sprung of a race indigenous to the coldest climate, he stands the heat better than our more delicate breed; and is, taken altogether, the best dog a sportsman can possess.

The nose of the Russian Setter is beyond comparison superior to that of English origin, and he will decidedly stand more work. Dog-breakers too have far less difficulty and trouble with the “Rooshians”, as they call them; for an erudite game-keeper told us in confidence not very long ago that they are “quicker at larning” than our highly-bred dogs, more tractable, and endowed with greater sagacity. Mr. Lang, of the Haymarket, has some of the best Russian Setters in Her Majesty’s dominions, and they are worth any money. We have seen some splendid dogs from a cross between the English and Russian Setter, and we look forward to the day when we shall have established in this country an invaluable breed.

A thorough-bred Russian Setter will do the work of four dogs: no gorse, furze, or hedge-row is too thick for him, and he will invariably retrieve his game. We hope to see this description of dog in more general use, for a little Russian blood will materially improve our English kennels. We do not mean to infer that we have no good blood of our own: on the contrary, we have too much of it: what we would urge is that it requires intermingling. We are too fond of breeding in and in, and sticking to one family; and the animals so begotten from generation to generation dwindle down into little, puny, fine-drawn specimens, which can never live out a long day. We speak from experience, having paid considerable attention and bestowed no little time and trouble on breeding and crossing setters. Our labor has not been thrown away, for we can boast of possessing as good dogs as ever went into a field, and to their surpassing excellence do we attribute the admixture of a little Russian blood.

Some four years ago, on our return from France, we pitched our tent in the South-eastern corner of Devonshire, on the confines of its neighboring county, Dorsetshire. It came to pass that being in want of an useful dog for the marshes, and one that would retrieve snipe and wildfowl, we wrote to an old friend in the neighborhood of Dorchester on the subject, and he most kindly sent us over . . . a Russian Setter worth his weight in gold. We have seen and owned some few dogs in our day, but never did we shoot over so extraordinary an animal as “Don.”

For nose, speed, courage, and sagacity we never beheld his equal: he would do the work of a whole kennel: no day was too long for him; his powers of scent were absolutely astonishing, and woe to the winged bird if it once touched terra firma: Don cared not for distance or impediments; have it he would, and have it he did; for, with every qualification a dog should be master of, he combined the art of retrieving his game. In short Don was a paragon of perfection. We shot to him a whole season, and before we returned him to Colonel D–D– we put him (not the Colonel, but Don) to a very handsome, clever setter-bitch, the property of a neighboring country Squire, and the produce turned out, as we expected, superlatively good puppies.

We sent one to our old and talented friend, Mr. Archer Croft, of Greenham Ledge, near Newbury, and Don junior is not only the handsomest but the best dog the Berkshire Squire has in his kennel, and a hundred guineas would not buy him. From this cross we have established an undeniably good stock to breed from. The whole of the litter turned out well: at six months old they stood, backed, and retrieved without any further tutoring than tying a wounded bird to a stake on the lawn, and teaching the young ones to fetch and carry a ball.

Another account, this one from the same Mr. Lang mentioned in Tolfrey’s article above, offers a few more details regarding the working style of the Russian Setter.

I found, from the wide ranging of my dogs, and the noise consequent upon their going so fast through stubbles and turnips (particularly in the middle of the day, when the sun was powerful, and there was but little scent), that they constantly put up their birds out of distance; or if they did get a point, that the game would rarely lie till we could get to it.

The Russians, on the contrary, being much closer rangers, quartering their ground steadily—heads and tails up—and possessing perfection of nose, in extreme heat, wet, or cold, enabled us to bag double the head of game that mine did. Nor did they lose one solitary wounded bird; whereas, with my own dogs, I lost six brace the first two days’ partridge shooting, most of them in standing corn.

. . .For all kinds of shooting therefore there is nothing equal to the Russian, or half-bred Russian Setter, in nose, sagacity, and every other qualification that a dog ought to possess.

Descriptions of Russian Setters were not confined to the English sporting press. Several articles were published in the US and Canada mentioning them, such as this one from Frank Forester’s The Complete Manual for Young Sportsmen in 1864.

The only remaining pure variety of setter to be noticed is the Russian, which is rarely or never met with in this country. It is an admirable creature, docile, good and gentle, to a charm. Enduring, beyond any other race of cold and wet, and dauntless beyond any other in covert, but more susceptible of heat and thirst than the others of his race. He is, I think, rather taller than the English or Irish dog, muscular and bony; his head is shorter and rounder than that of his family, and, like the rest of his body, is so completely covered with long, wooly, matted locks, tangled and curly like those of the water-poodle, only ten times more so, that he can hardly see out of his eyes.

His color is black, black and white, or pale lemon and white. I never saw one of any other color. I never have seen a pure one, though I once owned a half breed—a most superior animal—in America, nor are they common or easily attainable in England.

I learned to shoot over one in England, which I was permitted to take out alone, because it was well known that “Henry could not spoil Charon” and almost every thing that I know of shooting that old Russian taught me. He would not drop to shot, if a bird were killed, but dashed right into fetch; yet I never saw him flush a bird of a scattered covey in my life; for if the fresh birds lay between him and those killed, he would set them all one by one.

In the same way, if a hare were wounded, which he knew by the eye by some indescribable sign which no man could descry, he always chased and never failed to retrieve him. If he were missed or went away without a shot, he would charge steadily enough; but if two or three shots were missed in succession, particularly in the first of the morning, home he went in disgust, in spite of all threats or coaxing.

Russian Setters have what is called more point, they couch lower, and steal in more silently on their game than any other dog, consequently they are the best in the world over which to shoot game, when it is wild. Could they be procured, I think of all sporting dogs they are the most adapted for ordinary American shooting, and the best of all for beginners. They have less style,and do not range so high as the English or Irish dogs, but that is no disadvantage for America, where there is so much covert shooting.

One of my favorite accounts of Russian Setters in the field comes from an article titled “Shots Among the Prairie Chickens,” published in the January 29, 1886 issue of Forest and Stream. Since it not only mentions Russian Setters but paints a vivid picture of what prairie chicken hunting was like in the American midwest at the time, I can’t help but include it here.

Having little time and less money to spare last fall, but being—as usual—possessed of a very large desire to look at something over my gun barrels, fortune favored me one day late in September on meeting a friend who said: “I understand you have been out chicken shooting.” I had been up north about eighty miles, where, I was told, I could find a few birds, and I found them few indeed—I tramped for three days—got up a flock of six and divided even with them, taking three for my part, and came home. “Yes,” I said;—I have been out, but found few birds and no sport.” “Well,” he answered, “now I want you should lay out a trip and go with me.” I told him I could hardly stand another trip. “But,” said he, “this is my trip. You will go with me, will you not?” You would be almost surprised to know how little urging it required to induce me to say yes. As my friend had recently been presented with a fine Irish Setter but had no gun, he insisted I should go with him and select an outfit, which we at once proceeded to do and accomplished satisfactorily.

After making what inquiries I could for several days I nearly satisfied myself that all localities within a few hundred miles had been shot over. As this was toward the last of the month and the law was off on the first, if we decided to hunt within a radius of four or five hundred miles we should be obliged to glean the fields where others had reaped the harvest; so we decided to start for Nebraska, hoping to get beyond the market hunters, especially those who had hunted for this market, for the woods are full of them all over the West, and they are wiping out the game of all kinds as effectually as a fire licks up the prairie grass.

We bought tickets to Omaha, with a privilege of a rebate if we decided to stop anywhere this side; but after diligent inquiry at every possible point and opportunity we traveled across the States of Illinois and Iowa from east to west, receiving but the one answer, “The birds have been about all shot off.”

Now, this looks a little sad, that in two states, where but a very few years ago chickens enough could be found almost anywhere to make excellent sport, one should be told that the first month of the shooting season is over, that “The birds have been about all shot off.” It only reveals the truth that our game of all kinds is being rapidly and surely exterminated. I am aware that in the Great West everything is done on the “broad gauge” plan, and that a majority of sportsmen here think they must have a “pile” of game in order to get any sport out of it; but they will very soon have to moderate their desires and learn to get more sport out of less game.

We arrived at Omaha in the evening, and stopping overnight were told that a great many chickens had been shot about 100 miles west on the U. P. R. R. . We told our informant that we were not after chickens that had been shot, in fact we were not in the second-hand business at all, but had started for some locality where we could “sit down at the first table.”

The next morning we took cars and after riding about eighty miles in a northwest direction, we landed at the little town of Bancroft on the edge of the Omaha Indian reservation. A few moments’ conversation with the landlord, a Parker gun behind the desk and two Russian Setter dogs under the table, satisfied me that we had made no mistake in our location. I, being the commissary of the party, was ordered to make arrangements for our supplies during our stay, which I did by saying we should want a team at our disposal which would stand fire, enough to eat and a good bed to sleep on at night. “How long do you propose to stay?” asked the landlord. Our answer was: “Until we get satisfied.” The price was named and that settled it.

Prairie chicken shooting is par excellence the sport of the lazy man; it is the easiest of all land shooting—first, because the field is always open, and if one is too lazy to walk he can shoot from a horse or wagon; second, because early in the season, before the birds are quite matured, or have been too often disturbed, they will lie in the tall grass as close and long as one wishes; and thirdly, because they make a good big mark, flying true and not too rapidly, and there is so much of them that one need not fear of blowing them all to pieces, leaving nothing but feathers in the air. If they happen to get up too near for a shot, you can measure your distance, knowing there is no bush or tree for them to dodge behind. Thus in all respects,they make fine game for one not disposed to be in a hurry; and for these same reasons the gentle things are easy plunder for the unscrupulous market-hunter. Later in the season (or at the time we were out), during the last of September, the birds are fully matured, have become stronger flyers, and have been made a little more shy from an occasional shot among them, even in this far off locality, and will not always allow a dog to approach so near them; and if a bird gets up twenty-five or thirty yards away one has to wink his eye pretty quick in order to stop him, for being strong they will carry off quite a weight of shot unless winged or hit in a vital part.

. . .Our wagon was a comfortable two-seated spring wagon with a park top which would carry four or six persons and our dogs, and we had a couple of ponies somewhat larger than jack rabbits for a team which would walk or run all day, but manifested a most decided disinclination to trot. We had taken two dogs with us, an Irish Setter and English Setter and our landlord had two Russian Setters which were at our service, so we were pretty well fixed for an enjoyable time.

Our mode of proceeding was about this: We would get an early breakfast, load up dogs, guns, ammunition, lunch, a big jug of water for ourselves and the dogs; thus equipped our party of four, as reorganized, would point the ponies (which my friend named Splinters and Shanks) for the Indian reservation, when a ride of a little more than a mile would bring us on to good shooting grounds. We always drove to the leeward of the field over which we designed to shoot. Then we would get out, leaving Miss S to manage the team, following slowly in our wake and occasionally marking birds for us, which services she rendered in an admirable manner, and with a new and delightful pleasure to herself.

With the four dogs, the three of us keeping about two hundred yards apart and moving in line as nearly as practicable, each would generally find birds enough for his individual shooting without disturbing the others or placing them in danger; and when one’s pockets became too heavy for comfort or convenience, he would fall back to the wagon and deposit his load. Occasionally we would all meet at the wagon, when we would water the dogs, sample our lunch, a cigar, look over our birds, and when we had finished our chat and were thoroughly rested, start out for another tramp. Thus we would put in the time till about 11 o’clock, when it was time to bundle ourselves and dogs into the wagon and drive back to the hotel for dinner, after which came cigars and usually a game of cards till about 3 o’clock, when we would find ourselves again seated in the wagon and on our way for the evening shoot, which usually lasted far into the “twilight soft and gray.”

To me there is a rare and indescribable delight in shooting on a still, quiet evening, watching the last rays of the setting sun, and the last faint glimmer of light as it quietly passes away under the gauzy curtain of night. (May the last days of all good sportsmen be as quiet and pleasant.) We always found supper awaiting us on our arrival home, when after caring for the dogs and shedding our hunting traps, and taking a good square tin pan bath, we, “us four and no more,” would gather about the little round table aforesaid, doing ample justice to broiled chickens, flanked by vegetables, warm biscuit, pastry, etc.

After supper we would look to the comfort of the dogs, and then seat ourselves for a cheerful chat and game of cards till bedtime. Should you ask me now how many birds we bagged, I could not tell; I kept tally till we got past 100 and then quit. We did not forget our friends nor neglect ourselves, for we sent away a box each day, and kept a string hanging under the little porch of the hotel from which our table was supplied at each meal. Thus we passed the week, changing our route occasionally, always getting birds enough to make it enjoyable sport, never turning it into downright slaughter, and leaving birds “enough and to spare.” And with it all we had a good time.

Despite the various references to Russian Setters throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the description of the dogs is always unmistakably similar to that of a continental-type Griffon. Perhaps they were simply misidentified Wirehaired Pointing Griffons, or perhaps they truly were a unique strain of pointing dogs that eventually faded away to the pages of history. Either way, the Russian Setter remains preserved in the lore of turn-of-the-century hunting tales.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

I spent a lot of time in the USSR from Lemingrad to Petropavlosk and never saw such a dog. German Wirehair Pointes were common. I remember reading Tolstoy where he talked about a dog that pointed and then flushed on command.

Wonderful descriptions and stories, Craig. Many thanks. I wonder if the complete picture of the Russian Setter will ever unfold.

Whatever English-speaking authors may have written, one country that never ever heard of a dog called “Russian setter” is Russia. A few shorthair pointer breeds were created in Russia, the Marklovskaya Legavaya vor instance survived pretty much across the XIX century, until displaced by the English Pointer. But not a single Russian source from Login Krausold (1766) to modernity mentions a native wire- or longhaired pointing dog breed. Rough-coated pointers were indeed present and popular, but they were known as “Brusbarts” and said to originate in Germany or Poland. Interestingly, many old German authors also claim the wirehaired pointing dog came from Poland. As Poland was officially part of the Russian Empire at the time, that might explain the confusion.