Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was…

Learn about all the various types of bird feathers and how to identify them.

Feathers tell us all sorts of things about birds. They are beautiful to look at, help us identify individual bird species, protect birds from the elements, and they’re the reason birds can take flight. Ornithologists can tell us even more about birds thanks to feather measurements and samples. Some research labs even can measure where the carbon in feathers comes from, which tells us a lot about avian diets and migration patterns. However, before we get too deep down the rabbit hole regarding ornithological research, it’s important to start at the beginning. What are feathers, and how many types of feathers are there? To answer these questions, I consulted the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Handbook of Bird Biology from 2016.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

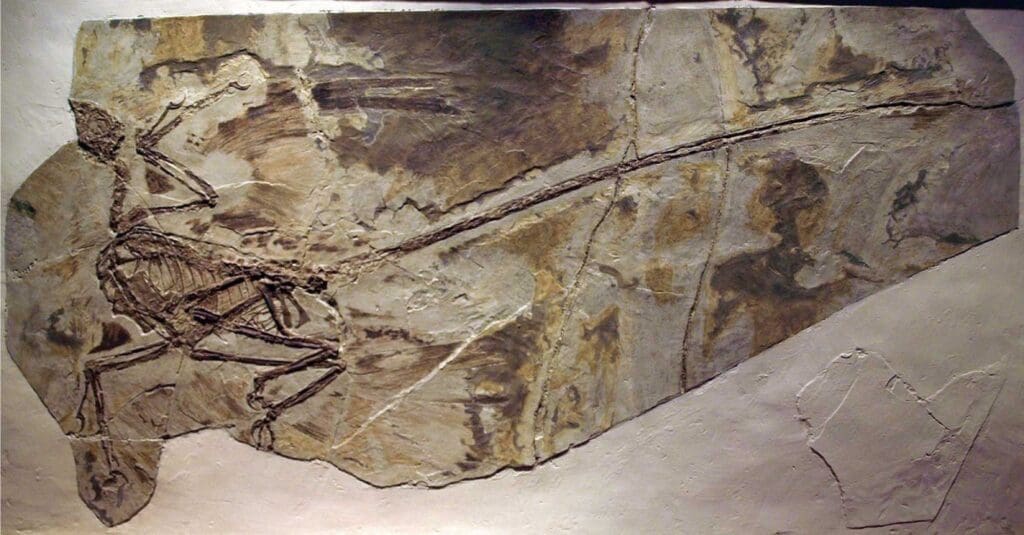

Birds are some of the closest living relatives to dinosaurs. Typically, we imagine dinos as giant, scaly, terrifying lizards lacking any decorative feathering. However, current research suggests that may only be the case for some prehistoric critters. In 2001, researchers analyzing dinosaur fossils found that the “hair-like” halos of organic tissue surrounding fossilized skeletons consisted of beta-keratin, which is only found in feathers and reptile scales. From that point forward, researchers began referring to these structures as feathers. Today, it’s widely accepted that many theropods and other dinosaurs had primitive feathers. If you really want to nerd out, give the four-winged Microraptor gui a Google.

If you’ve ever plucked a game bird, you’ve probably noticed that different types of feathers grow on different parts of the bird. Groups of varying feather types are called pterylae. Conversely, some places along birds’ bodies don’t grow feathers and remain bare skin. These bare spots are called apteria. Together, these tracts of feathered and featherless areas are called the pterylosis.

Feather types along the pterylosis vary by their “aerodynamic, hydrodynamic, insulative, repellant, acoustic, and visual properties.” Plainly speaking, different groups of feathers are good for different things. Some are meant for flight, others to keep birds warm in frigid temperatures. Other feathers are purely for attracting a mate in the spring. Keep in mind that these groupings are simply convenient ways to categorize similar-looking feathers, and there are many exceptions to these rules. However, familiarizing yourself with the physiological features of beloved bird species enhances our human connections to them and deepens our appreciation for the natural world.

Insulatory Down Feathers

Most folks are familiar with down feathers. Down is a standard component of pillows and winter coats and is easily identifiable on game bird species like ducks and geese. If you refuse to let valuable parts of birds go to waste like our Director of Operations Jennifer Wapenski, you might even harvest the down off your waterfowl while you pluck them in preparation for the dinner table.

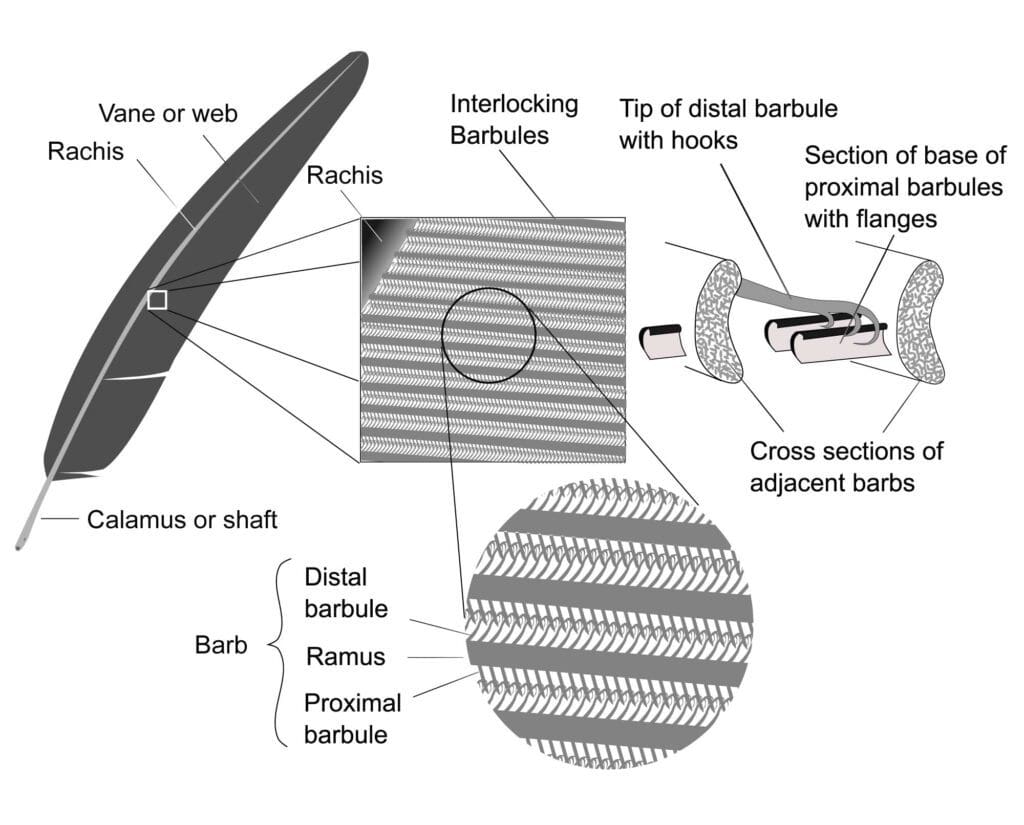

Down feathers are the simplest type of feather. Their rachis, or the feather’s central quill, is shorter than the longest barb, or the tuft-like strands that come off either side of the rachis. Additionally, their barbs are “entirely plumulaceous.” This property allows them to trap air, making them incredibly lightweight insulators. Down is also what makes nestling birds look so fluffy and cute.

Not only are down feathers excellent at insulating adult birds’ bodies, but they’re also a common nest material. Many waterfowl species pluck down feathers out of their breasts and line their nests with them, which helps thermoregulate their eggs.

Distinguishing Contour Feathers

Contour feathers are what cover the majority of adult birds’ bodies. They give birds their iconic round shapes. These feathers are defined by having a rachis longer than the longest barb, and “at least a portion of the rachis contain a pennaceous vane.” Pennaceous vanes are made up of pennaceous barbs, which are the opposite of plumulaceous barbs. These barbs are stiff, pointy, and held tightly together by many barbules. Think of barbules like a meta-barb; they’re the tiny barbs that are on the larger barbs. Barbules are what let the tips of feathers stick back together if they’ve separated when you run your fingers over them.

These exterior feathers are great at streamlining a bird’s body, reflecting sunlight, repelling water, holding in heat, and deflecting wind. They’re typically colorful and aid in camouflage, attracting mates, or both. Sometimes, contour feathers contain an additional afterfeather; if you’re a grouse hunter, you’re likely already familiar with afterfeathers. Grouse are known for that small, secondary feather that grows from the same feather follicle as a contour feather. It’s completely plumulaceous and aids with insulation, especially in cold climates like New Hampshire or Colorado.

Stiff Flight Feathers

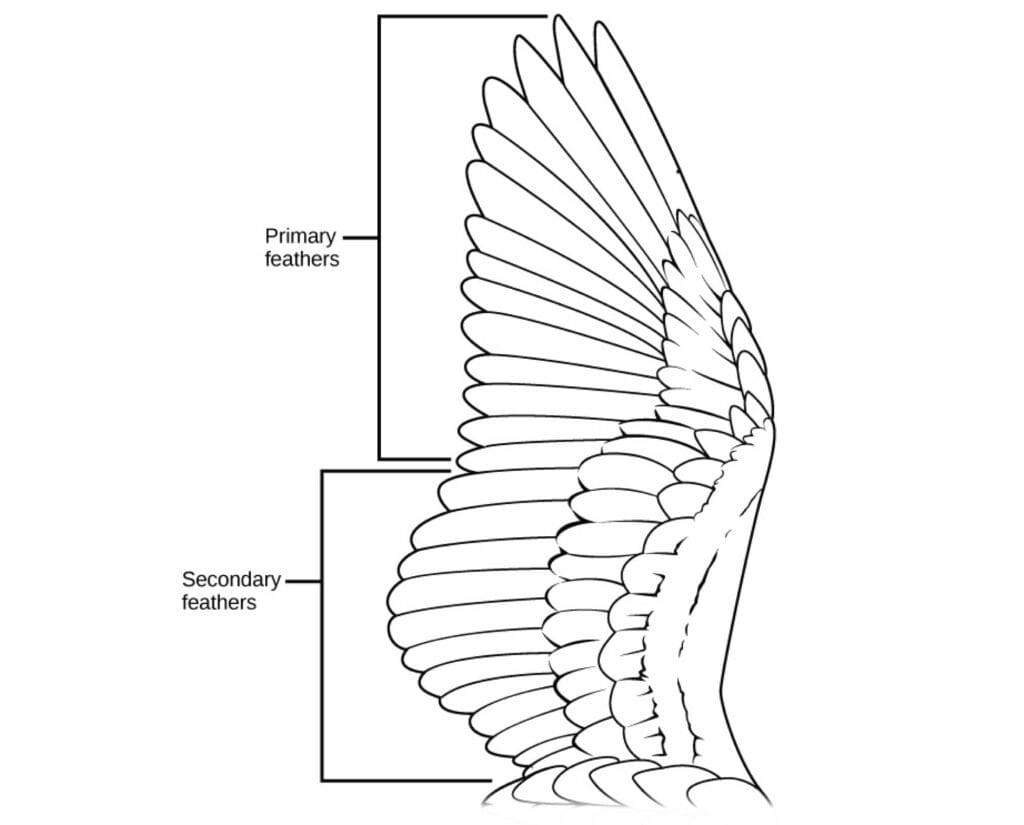

Flight feathers are self-explanatory; they’re the feathers located on the wings and tail that aid in flight. Wing flight feathers are called remiges, and tail flight feathers are called rectrices. Unlike contour feathers, remiges are attached to the wing bones via ligaments. Ligaments also connect rectrices, and the most central pair of rectrices are attached to the tailbone.

The outermost, or distal, remiges are called the primaries. These are the feathers most biologists are interested in regarding measurements and field sampling. Secondary feathers are the inner wing feathers. If you want to nerd out again, you can memorize the numbers corresponding to each primary and secondary remige and all the rectrices.

Specialized Feathers

Down, contour, and flight feathers are easily identifiable and generally familiar to anyone who spends time in uplands. However, birds have a few other feathers that are less recognizable yet highly specialized and contribute to the finer details of upland bird species.

Semiplume feathers

Semiplume feathers are somewhere between a contour feather and a down feather. Typically, their rachis is longer than the longest barb. These feathers don’t have a pennaceous vane at their tip; however, they retain more form than pure down feathers. If you enjoy fly tying, marabou should come to mind when you think of semiplumes.

Bristles

Bristles are tiny, stiff feathers that primarily consist of a rachis. They are almost exclusively located on birds’ heads. Think of those sage grouse eye combs or the fine “hairs” that line the edges of a barn swallow’s beak. Bristles, specifically rictal bristles around the beak, were previously thought to funnel insects into a bird’s mouth. However, research from 1980 provided evidence for that hypothesis to be untrue. Alternatively, they found that more particles entered a bird’s eyes when their bristles were taped down, and now our best understanding of their purpose is to keep the eyes debris-free during flight.

Filoplume feathers

Filoplume feathers are the smallest feathers on a bird’s body. They’re unmistakable due to their long, bare rachis tipped with minuscule barbs. These are often the “hairs” you can’t pluck off when cleaning your game birds; most folks burn them off with a lighter. Instead of being controlled by the musculatory system, filoplumes are connected to the nervous system. It’s believed that birds use filoplume feathers to alert them when their contour feathers are disheveled, which typically triggers birds to realign their feathers, which aids in efficient thermoregulation.

The next time you pluck a grouse, quail, or duck, pay attention to its particular feather types. Identify its third primary, save its down, or when you go to remove the tail fan, check out the ligaments that connect those rectrices. Or maybe you’ll get annoyed at the filoplumes that just won’t come off. Either way, being an informed avian enthusiast can only enhance your relationship with these birds we all religiously pursue each fall. Familiarizing ourselves with ornithology and bird conservation is the least we can do to repay these species that give us so much.

Gabby Zaldumbide is Project Upland's Editor in Chief. Gabby was born in Maryland and raised in southern Wisconsin, where she also studied wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2018, she moved to Gunnison, Colorado to earn her master's in public land management from Western Colorado University. Gabby still lives there today and shares 11 acres with eight dogs, five horses, and three cats. She herds cows for a local rancher on the side.