Home » Woodcock Hunting » Targeting Worms with GIS Soil Data to find Woodcock Habitat

Targeting Worms with GIS Soil Data to find Woodcock Habitat

Jesse St. Andre is a native New Englander and is…

A woodsman tests theories of targeting worms for good Woodcock habitat

If I could smell a bird, walk effortlessly through thick brush, and cover ten times as much ground as the average human, Woodcock hunting would be a breeze. If I had a dog which could do all these things, Woodcock hunting would be even more of a breeze.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Unfortunately I can’t smell birds, I’m a slow walker, and I don’t have a dog.

The problem is that I’ve grown increasingly fond of hunting American woodcock. I am a dog-less hunter with a young family and limited time to hunt, so pounding the ground in search of good woodcock cover just isn’t an option. As a lifelong deer hunter and avid trapper, I do more than 50% of my scouting on a computer. It might seem a a bit unorthodox to adapt this aspect of my deer hunting to woodcock hunting. But so far, it’s paid off.

Having experience using GIS maps from my days as a forester, I started looking at areas where I’ve flushed/shot woodcock in the past. I wanted to see if there are certain attributes that all these areas have in common. I placed a mark on the map for nearly every flush I could remember, utilizing dozens of different map layers. It became pretty obvious that there were several characteristics each spot had in common. A couple, however, stood out more consistently than others—a soil and vegetation type.

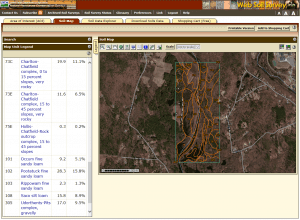

The USDA has a “Web Soil Survey” website where anyone can view all the individual soil types in any particular area in the nation. The soil types which are the best for holding Woodcock will vary depending on geographic region. Simply zoom into a few of your favorite Woodcock covers and see what type of soil is present. You should find that the majority of your Woodcock covers will consist of the same soil types. Using this information, you can then look on the map and find new areas with the same soil type.

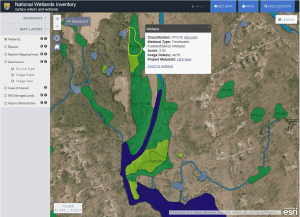

The second common denominator of each cover was the type and density of vegetation present. The tree and shrub species present in my known Woodcock covers are consistent with the species that grow in certain wetland habitats (e.g. forested/shrub wetlands). Using a simple “Wetland Layer” available through the USFWS, I could identify all my known Woodcock covers to within just a few yards.

While this “Wetland Layer” accurately depicted ideal Woodcock habitat in New England, other areas of the country may vary. This assumption behind using this layer is that certain tree and shrub species only grow in very particular environments. The primary species that grow in these forested wetland areas are: speckled alder, red alder, boxelder, willow, dogwood, and bottlebrush in the understory, and poplar and maple in the upper canopy. This is consistent with ideal Woodcock cover for my region.

Armed with these two simple map layers, I spent just a few hours on the computer and identified several areas of potential woodcock habitat. After arriving at the first area, I found myself walking directly past hundreds of acres of thick cover consisting of birch, poplar, cherry and hornbeam. Normally, I would have tried to hunt through this.

Once I reached the area on the map with both the ideal soil and vegetation, I began hunting and flushed six Woodcock in the first hour. I’m not a great shot, however. So with the one out of five Woodcock, I made my way back through the hundreds of acres of thick dense cover outside my identified area. I never flushed another bird. The vegetation was thick and seemed like ideal Woodcock habitat. Unfortunately, the map showed the soil was mostly sandy with lots of rocks, which is bad for worms.

This pattern held true for the next four areas. At that point, I was sold on the technique. With the knowledge and a little confidence, I have since identified more Woodcock covers than I have time to hunt. All within twenty minutes of my house. Each one holds enough Woodcock for a dog-less hunter like myself to flush and reach limit in an hour. I can only imagine that this method, in combination with a good hunting dog, would be nothing short of epic.

Jesse St. Andre is a native New Englander and is a lifelong hunter and avid trapper. He holds a degree in Forestry and works for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife as a Hunter Education Specialist introducing others to the Outdoor sports.

Interesting. In Robert McCabe’s book, “The Professor”, he recalled finding Aldo Leopold in his office pouring through soil maps of areas they would hunt woodcock in that day.

That was back in the 1930s. Leopold, an avid grouse and woodcock hunter, knew all to well they’d find woodcock where the worms lived!

That is very interesting! Clever clever.

I’m an upland bird hunter in AZ and use GIS on a regular basis for hydrology/flood control studies. I love this approach and now I’m curious about how I can do something similar to help find quail spots here.

We would love to hear more about it if you stumble onto something!

I know it has been awhile since you wrote this but thought I’d share my use of GIS in identifying potential hunting areas. Nevada publishes an atlas with the location of all water guzzlers (1,725) that I’ve plotted in Google Earth Pro. With the addition of topo, watershed, streams and streambrook layers, and Chukar distribution plots I’ve created a pretty good mapping of “ideal” locations for Chukar. Now to put it to work. Will have to share the results later in the season.