Home » Waterfowl Hunting » Legacy of the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox

Legacy of the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox

Mike Adams is an outdoor writer, wildlife biologist, and educator…

The Barnegat Bay Sneakbox is a waterfowling boat legacy that has lasted generations and adpated with the times

Golden waters run in the twisting rivers that weave through West Creek, New Jersey. It trickles in from upland pine forests, where pine needles leach tannins and tint clear water with an amber hue. The water carves through cedar swamps and pours into the estuaries. Here, saltwater blends with fresh. The mix creates a brackish marsh that holds thousands of wintering waterfowl every year.

West Creek overlooks the marsh like a shepherd tending a grassy vista filled with sheep. It’s a town that takes pride in its waterfowl, and it’s a town anchored by tradition. Rotten plywood signs hang by single rusted nails above the shed doors that line West Creek’s streets. They’re labeled Decoy Shop and Boat Yard in blistered, dripping black paint. Stained tobacco pipes hang loosely from their owners’ cracked and dried lips as they whittle away at cedar mallards and black ducks, pintail and teal. They wear faded flat caps and stiff flannel jackets cloaked with sawdust. When they’re not at work, they’re on the marsh. Waterfowl hunting runs as thick in the veins of West Creek’s townsfolk as the water runs gold, and at the heart of it all lies the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox.

The legacy of the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox

The Barnegat Bay Sneakbox chiseled its legacy back in 1836. Captain Hazleton Seaman of West Creek began a mission to create the ultimate duck hunting boat. Hazleton was a waterfowler and expert craftsman. He hunted the marshes surrounding Barnegat Bay, about ten miles from West Creek as the duck flies. Like all tidal creek duck hunters, he battled against shallow bays, icy winters, wary ducks, and unforgiving terrain. He needed a boat that he could both row and sail. It had to be sleek enough to conceal in salt marsh sedge yet durable enough to survive ice floes and rough surf. Above all else, it had to be a boat specifically designed for duck hunting.

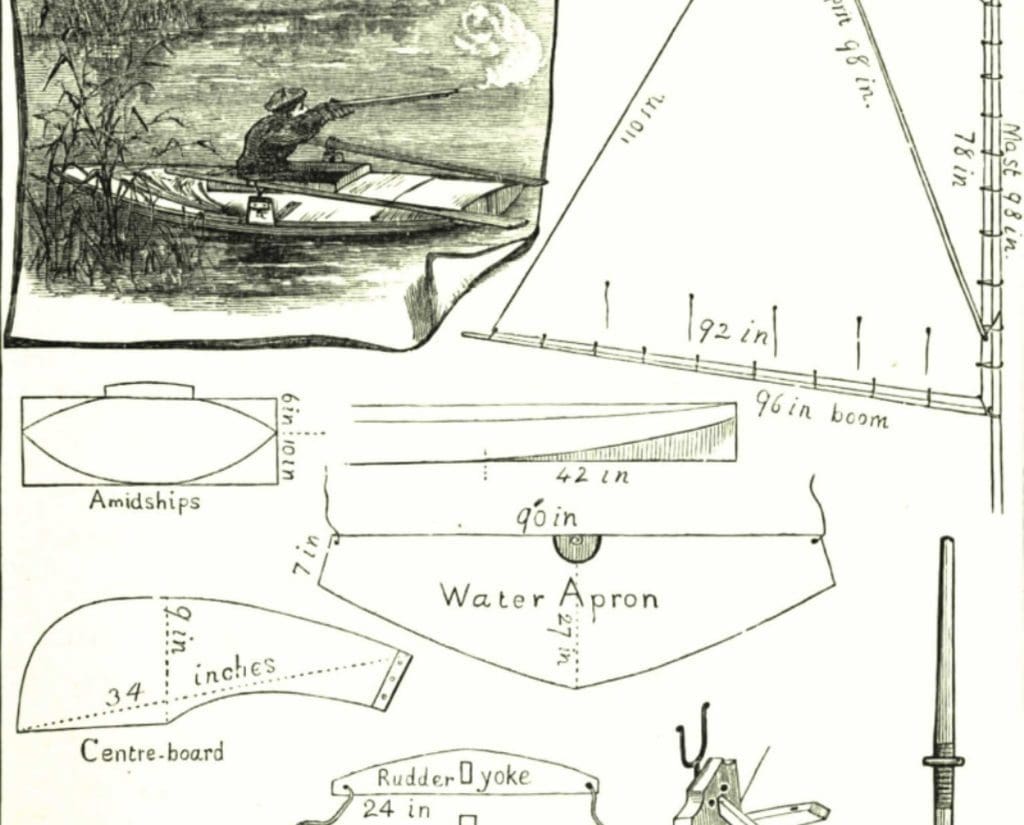

Seaman’s creation was the Frankenstein of duck boats. It had the cover of a ground blind and the hull of a skiff. It had an elongated, convex frame like an eye contact lens. The hull acted like a sled on mudflats, ice, and snow. It could be rowed or sailed. Its ribs were water-resistant and crafted from lightweight Atlantic white cedar, giving it a local flare tailored for the marsh. From the side, the boat was barely a foot tall. It could hardly be seen as it skipped like a stone across the water. He built gunnels that served as decoy racks and a flat deck that could be manicured with cordgrass and salt hay for camouflage. He stretched canvas across an oak hoop and fastened it to the bow. The apron laid on the boat like a raised fingernail and shielded the rider from sea spray. In the middle of it all, Seaman built a cockpit where duck hunters could slip in and sink low as if they were in a layout blind. Seaman named his creation the Devil’s Coffin. The local baymen dubbed it the Barnegat Bay Sneakbox.

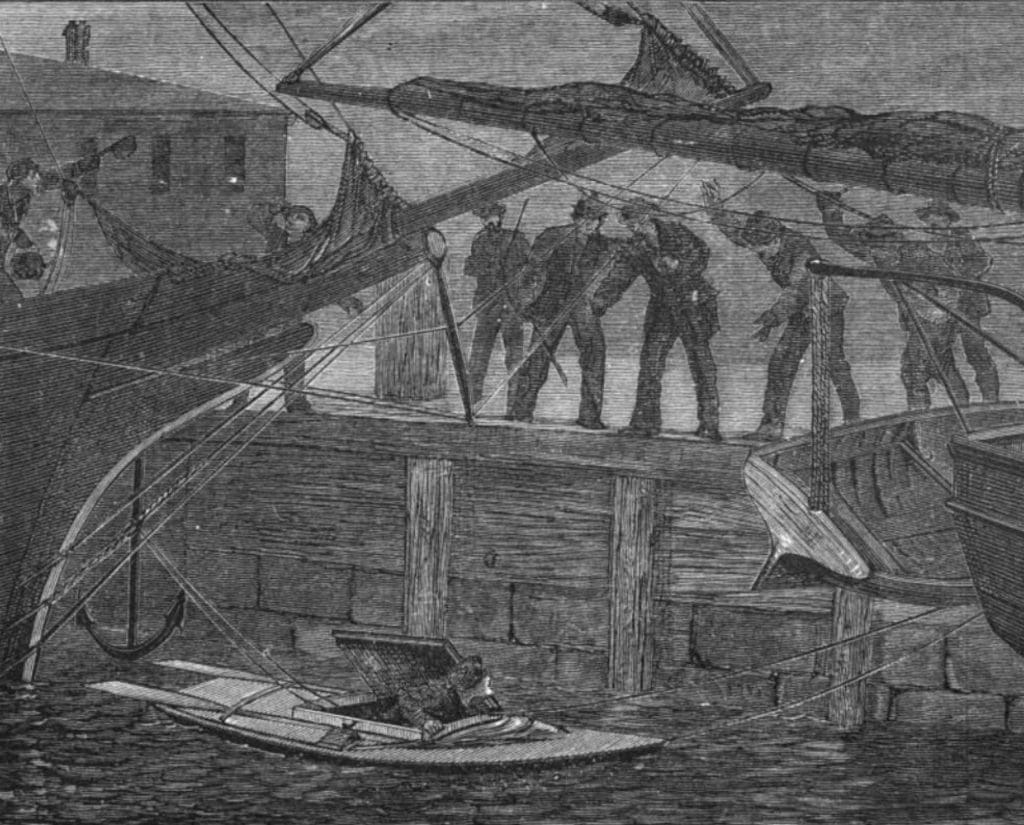

In Seaman’s sneakbox, hunters could row within shooting range of unsuspecting ducks or simply tuck up among some grass behind some decoys. In the grass, the boat disappeared, and duck hunters could fool birds all day long without getting busted. Its usefulness didn’t go unnoticed. Suddenly, sneakboxes hoarded winter marshes from the tip of Cape May to Long Island Sound.

The rise in popularity of the Sneakbox

As the boat rose in popularity, backyard artisans began improving its initial design. They modified spray shields and custom-tailored the gunnels. Hazelton’s boat evolved and sprouted into dozens of varieties that differed in hull dimensions, lengths, and weights. Some of the best were created by Captain George Bogart of Manahawkin. Bogart built his sneakboxes in his yard, surrounded by thick swamps and dense cedars. One sunny morning in the fall of 1875, while Bogart labored on a new boat under the shade of a willow, a bright young adventurer from Medford, Massachusetts, came strolling down his driveway. His name was Nathaniel Bishop, and he requested a sneakbox of his own.

Bogart sold Nathaniel a custom-made twelve-foot, two-hundred-pound sneakbox for $25. Nathaniel bought oar locks, oars, a sail, an anchor, and other outfits for an additional $50. Nathaniel named the ship the Centennial Republic to commemorate the hundredth year of America’s existence. Bogart helped seal the Centennial in a protective layer of burlap before Nathaniel shipped it on a freight train from Tuckerton, New Jersey, to Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

Nathaniel detested leaving his brand-new boat, if even for a second. He called it “a necessary evil” for a voyage. Nathaniel eventually caught up with his sneakbox in Pittsburg and embarked on an epic four-month-long journey down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. He rowed it the whole way, living and eating out of the boat’s cockpit, skirting through bluegrass fields, and paddling his way through a post-Civil War American south. Eventually, Nathaniel and the Centennial poured out into the Gulf of Mexico and landed on the mouth of the Suwannee River, where his adventure ended. In 1879, he published a book about his 2600-mile journey, aptly named Four Months in A Sneakbox.

By 1909, Ole Evinrude invented the outboard motor, and the sneakbox evolved a transom. A duck boat built on a tradition of rowing and sailing could now be outfitted with an oil and gas motor; this is the sneakbox we see today. There’s the fiberglass Higbee and the wooden Sammy Hunt, the low-profile Schellenger and the planing-hull Simonsen, each variation taking on the name of its builder, imbued with an individual touch of creativity and innovation. The trait that makes each of these boats a true Barnegat Bay Sneakbox is the crafted purpose, down to every rib and every nail, to hunt ducks.

The modified Sneakbox may be the best duck boat one could hope for

Today, sneakboxes dip in and out of the water at boat ramps all along the mid-Atlantic shore, but nowhere more so than the marshes of southern New Jersey. When fellow sneakbox owners run into each other, it often results in an understanding nod and immediate kinship. It’s a club built on art and utility, the owners bearing on their backs a weighted tradition that has been reduced to obscurity and esoterism. It’s a responsibility expressed through pride. Those who hunt out of a sneakbox know just how deadly they can be, but others simply enjoy the craftsmanship. They enjoy a ride in a sneakbox for the art, for the history, and for a little taste of what Nathaniel Bishop experienced when he took the Centennial Republic all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. Regardless of its design, or the intentions of its rider, sneakboxes have an uncanny ability to exude emotion from those who own them. The waterfowl writer Worth Mattewson sums up his feelings on the sneakbox in his book, Big December Canvasbacks.

“There is simply no one ‘best’ duck boat. But for a very wide range of hunting, the modified Barnegat Bay Sneakbox made in fiberglass comes about as close as could be hoped for…”, he continues, “Of course it looks best out in the marsh, but during the off-season, I’d bet I never walk past the two sneakboxes I own without subconsciously admiring them.”

Mathewson’s words rang true on a recent hunt out in the salt marsh fringing the shores of Cape May County, New Jersey. Boone, my golden retriever, and I overlooked a burning-red horizon with a stiff west wind to our backs, sunk down low and nestled into a sneakbox. It was a Higbee, one that my grandfather purchased out of a backyard in the 80s, crafted from fiberglass with decoy rack gunnels and a spoon-shaped hull. We tucked deep into a tidal ditch that drained straight to mud at low tide. Cordgrass bent and folded over our twelve-foot boat, and through their blades and the mud and the morning dew, Boone and I studied a small decoy spread. The cackles of clapper rails echoed through the briny morning air as the sun rose high above a cedar-flanked horizon.

It had been nearly two hundred years since Hazleton laid the foundations for a hunt like this. Just when the cold of the deck began to seep through my waders, the stillness of the marsh cracked to the sound of whistling wings. Boone snapped his head, and I followed. Two black ducks careened above, and they had no idea they were flying straight for a Barnegat Bay Sneakbox.

Mike Adams is an outdoor writer, wildlife biologist, and educator hailing from salt marshes of the mid-Atlantic. His work has appeared in numerous outdoor publications, where he uses hunting and fishing narratives to explore deeper issues in conservation or ecology. In the fall, you'll find him on his Barnegat Bay Sneakbox hunting ducks with his dog, Boone. Any other time of year, he's usually out on the salt marsh, catching crabs or fishing for striper.