Home » Hunting Dogs » Transitioning a Dog from Training and Testing to Hunting Wild Birds

Transitioning a Dog from Training and Testing to Hunting Wild Birds

Jason Carter is a NAVHDA judge, NADKC member, director of…

This guide will help you troubleshoot and transition onto wild birds with your pointing dog this hunting season

“Time’s up! Please turn in your exam,” announced my Biology 101 professor. Are you kidding me? There are time limits on tests? Did I even use the right study guide? Feelings of bewilderment and dejection swelled in me as I sheepishly handed over my first big test failure during my freshman year of college. It was a wake-up call to the fact that I wasn’t in high school anymore. Eventually, I figured out what it took to be successful, and I made my way through the course.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Just like a high schooler entering the real world, an accomplished dog in its testing doesn’t necessarily mean it’ll be an accomplished dog on wild game. In fact, I can almost guarantee that there will be an adjustment period. Until the dog bridges the gap from training birds to wild ones, they’ll flounder. This begs the question: why do dogs sometimes struggle to make this transition? Also, what is our part as handlers in helping our dog make the transition? Here’s my reasoning behind why many dogs struggle finding and pointing birds during hunting season and some suggestions to help them transition.

Liberated at Last: Moving Away From the Training Microscope

When hunting season comes and folks hit their favorite spots with aspirations of heavy game bags and sore shoulders, questions start coming in from frustrated new handlers. Dan Riley, a new Brittany owner and late-onset hunter inspired this article. He recently qualified his Brittany in NAVHDA’s Utility test, earning a maximum score. However, since the season started, Dan has been in constant consult attempting to bridge the gap between summer training and hunting. Why is my dog breaking? Why isn’t my dog pointing? These questions have been on his mind every day since the 2022 hunting season began. After getting a month of hunting under his belt, I asked him about what he’s learned thus far.

“For those of you with young dogs or dogs that have a natural tendency to range, remember your role. Your job is to be the leader and dictate the cadence and pace of the hunt,” said Riley. “My job is to reign my dog in with a come around/whistle command to change the direction of her search for birds while not interfering with her expertise with finding the scent cone. This task takes effort and focus. When I do my job well, there is a remarkable difference in the outcome of the hunt.”

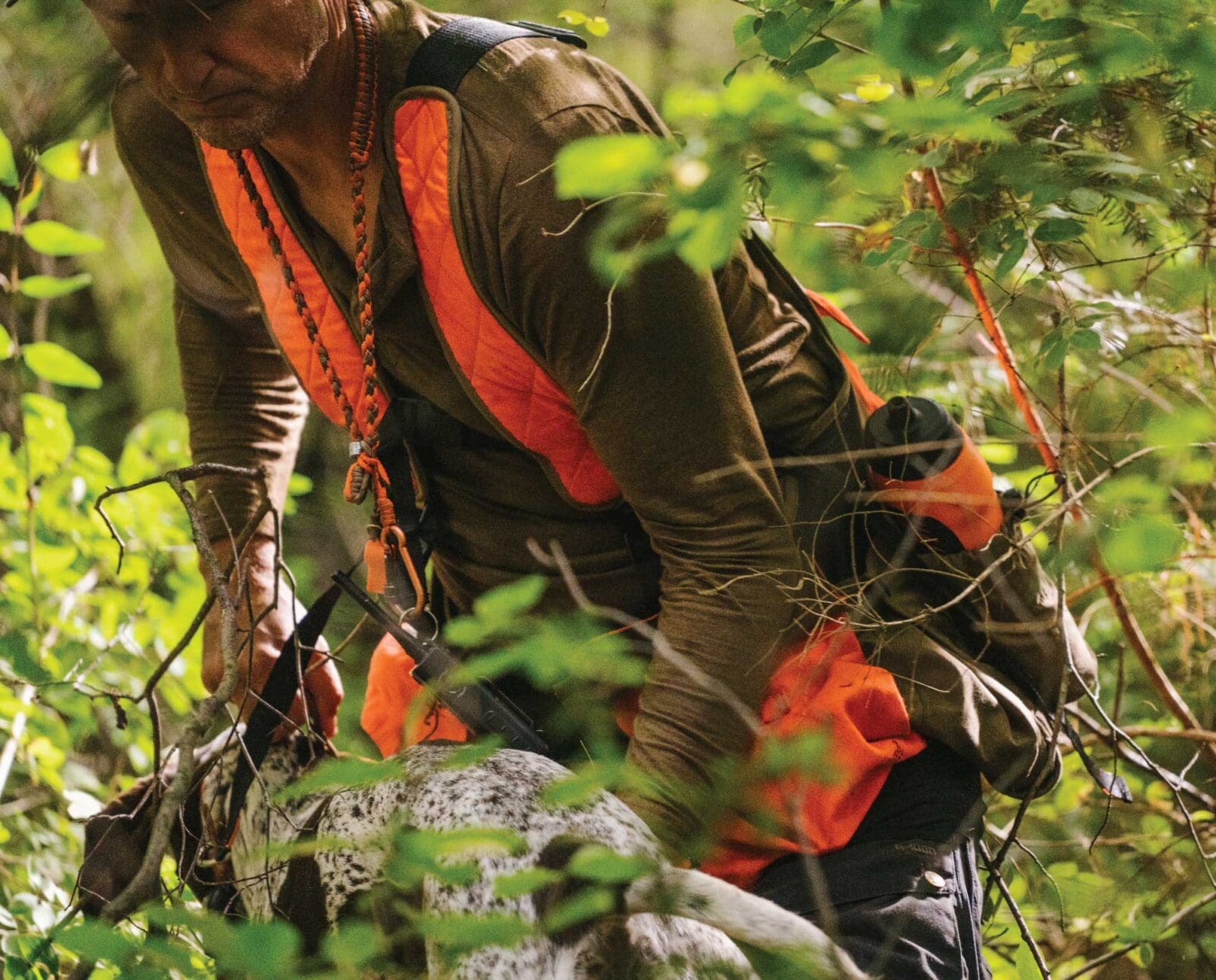

Similar to my freshman year, the hunt has become more challenging for the dog. Adjusting to the unyielding terrain along with the challenge of finding and pinning wild birds takes time. Also, the handler’s focus has transferred from the dog to the birds. Training is over. Killing birds has begun, and many handlers leave the dog to figure things out on its own. Though some dogs seamlessly make the transition from training to hunting, most dogs require time, patience, and guidance to get up to speed.

Liberation from the dog training microscope and the discovery of bountiful bird opportunities leaves the dog on unfamiliar grounds. It’s an all-you-can-eat-buffet to a new pup. To the dismay of many handlers, young or early season dogs may rip through coverts, overrun birds, and take out anything that wiggles. You may be meeting this new version of your dog for the first time, which can be concerning. However, it’s a normal developmental step in the finishing process.

Unfortunately, some of us have to address this each and every season. For those who are fortunate enough to live in states that allow training on wild game, this phase of training can be addressed prior to the opener. However, even with well trained, veteran dogs, there are times when some tweaking needs to be done, especially once you begin killing birds again. It’s a process we all go through to bring the dog back into balance and connect training to hunting. For some, this is a quick, early season lesson that reminds the dog that all rules still apply. For others, it remains a daily routine to keep the dog attached to us and honest around game.

The Nose Knows: Transitioning From Training Birds to Wild birds

To be reunited with the dog you once trusted, first identify why a dog sometimes struggles bridging the gap from training to hunting. One reason is that the nose hasn’t been honed in on the birds you’re targeting. Until you’ve eaten french fries, the smell of McDonald’s doesn’t make your mouth water. Similarly, until you expose your dog’s nose to its target wild bird species, it doesn’t understand what you are after.

A dog’s entire world is seen through the lens of scent. A nose is a muscle that gets strengthened through hunting experiences. The stronger the nose, the farther out the pointing instinct is triggered in the scent cone. In the end, strong-nosed dogs pin the most wary of birds for the gun. From the smell of our bird bag, launchers, shotgun, and vest, a dog is aware of its job and our expectations that have been associated with those scents. When associative scents are removed, as they are during hunting season, a dog may revert to aimlessly exploring the world. It’s our responsibility to put purpose into the dog’s hunt and provide the understanding behind all those exciting smells, helping bridge its training to the new environment.

Too often, the failure to point or constant breaking catches handlers off-guard. They become frustrated with their dogs, not understanding that the leg work is already there. Handlers only need to overlay their training to the hunt and remain relevant to the dog. A dog running helter-skelter is not thinking about its handler; reuniting the dog with us using recall commands, whoa work, and other familiar obedience tasks puts us back on the map.

Also, keeping the dog in our visual presence makes it far more likely to remain steady. If you watch carefully, you’ll notice your dog giving you a glance now and again, providing itself with visual direction and affirmation. It can be subtle, but a compliant dog keeps tabs on its handler. However, compliance starts at the truck. A dog that bullies its way out of its crate often foreshadows selfish, unsteady work on birds. Be an advocate for your training program. Insist on compliance from start to finish. The dog will come back into balance and begin to settle, allowing it to think again and eventually bridge the gap from training to hunting. It will be like a light switch went on; you will reunite with your dog again.

Be Present: Remaining Relevant to Your Dog

Wild birds tend to be far less forgiving of a dog that needs to get deep into the scent cone. They get up early, run, and use the terrain and survival instincts to keep distance between the dog and itself. It’s a game of chess played between the bird and your dog. In these cases, we let the bird teach the dog. One thing we can do to steepen the learning curve is to not let the dog become overexcited. Remain present in the process. Slow down the dog, take breaks, and be sure your dog remains calm and connected to you. It’s certainly a tall order in the face of large coveys or flights of birds, but out-of-balance or over-excited dogs are often the reason for the loss of pointing.

“Reinforcing the whoa command is something I learned and remember to do most of the time when my young Brittany goes on point,” said Dan. “My role is to harness that drive so we can succeed as a hunting team.”

It may take a lot of time and boot leather to teach a dog to keep its wits about it, but it will master wild birds provided it is given enough time and experience.

The Big Dilemma: To Shoot or Not to Shoot?

The “if it flies, it dies” mentality is a common mindset once hunting season is upon us. We haven’t trained all season to let birds fly away, right? Something to consider, and don’t shoot the messenger, would be to not reward a breaking dog with a retrieve. Forego some shots, and if need be, put your gun away early on to steady up your dog. Maybe allow a friend to do the shooting until the dog steadies up. The closer we keep hunting expectations to our training expectations, the more reliable and honest our dogs will become, making the transition from testing to hunting far easier for the dog.

“Remember to keep your focus on the most important component of the hunt: your dog,” said Riley. “As a handler, I have an obligation to set my ego aside and put my dog’s joy and development at the forefront of every hunt. I have seen days of perfection with beautiful points and sometimes remarkable blind retrieves. Other days have been more like ‘Brittanys gone wild.’ My dog counts on me to help her have the best hunt possible by setting her up to hunt with me every moment that we are in the woods.”

Is Your Dog Mentally Balanced in the Field?

“Is the dog with you mentally?” is a good question to ask yourself during a rough patch on a hunt. In the presence of lots of game and gunfire, the excitement of the hunt can draw out predatory instincts. If the team mentality is falling apart, your dog’s mind may be out of balance. It’s never good for your dog to be out of balance. It’s not safe nor good for the hunt.

The frequency of mentality work depends on what your dog communicates to you. If you notice that the dog is overrunning birds with a pie-eyed look, it’s way out of balance. This crazed animal is unlikely to have any connection to you and will make for a rough day of take outs and self-hunting. To bring these dogs back into balance, slow everything down, reel your dog in, and keep it close; control comes with proximity. Take his opportunity to go back to your basic training drills such as whoa, staunching the dog, come to a finish, or mimick a wild flush with a thrown bird and a shot. Even consider putting your gun away for a bit. Reminding the dog of your presence and control often grounds it, making you relevant once again.

READ: How to Reset Your Dog in Training

If your dog’s mentality is pressure related, the fix is easy. Get the dog on as many birds as possible and forego any steadiness or obedience. Shoot wild flushes and give the dog the time of its life. Take your time and let the search grow. You can get your steadiness back quite easily, though its the search that might take some time.

When it comes time to resteady your dog, follow the least-to-most approach. Be vigilant about the mindset and reaction to the pressure reintroduction. Drop the pressure to almost zero. Normal correction levels will be too abrasive. Take your time, and let the dog acclimate to it; you’re trying to work through the dog’s insecurities. If the prey drive is there, the dog should pull out of it in short order. This is one of the situations where being cognizant of the mental state of your dog will tune you in on how to move forward.

Dogs that hang too close are of little use to hunters. If you find that the dog is restrictive in its hunt, you’ll need bird numbers. Heavy obedience is your enemy. For these dogs, you want to move and make the hunt exciting. Your goal is to get the dog comfortable at a distance. You want to teach the dog its okay to get away and that there are birds out there to find without pressure. Hopefully, prey drive will kick in and pushes the dog out.

When considering a restrictive dog’s motives, explore the idea that it doesn’t like gun fire. The hunt may have been taken from the dog through poor gun acclimation or too much pressure on birds. If you find that the restrictive search is due to gun sensitivity, this becomes a far more delicate process. If your dog is gun shy, stop hunting. Start your dog on an approved gun desensitization program.

When hunting over a gun sensitive dog, it’s imperative that the dog is either chasing or visually connected to the bird during the shot. A problem we see here in the northeast is the dense cover obscuring the bird from view of the dog. Shooting wild birds out of sight of the dog will compound sensitivity issues. Another issue is the random gunfire of other hunters. Though not over your dog, the low, concussive tone will trigger the same fear response. Many of the dogs we see showing signs of gun sensitivity are predisposed to the issue. Its nervous system is as such that loud or novel noises trigger a fear response. For these dogs, their prey drive must be through the roof, and a proper gun neutralization process must be followed. These dogs should be allowed to mature a bit longer, and given a slow, methodical approach to the gun acclimation process.

Steadiness Training On Wild Birds

Your approach to steadiness on wild game should mimic the training you did leading into hunting season. The dog should feel that the hunt is an extension of your training. There are many systems of training out there for training steadiness, all of which have proven success. It will be your job to pick one that works best for you. For us, the whoa command is the cornerstone of our training system. It’s a system developed from a family friend and the founder of NAVHDA, Bodo Winterhelt.

The stop action command of whoa starts on a training table with a short lead, then moves to the ground, eventually out to the long lead, then onto small grounds overlaid with the e-collar. If everything goes well, we move onto large, open grounds. There are many steps in between, though the idea is to shape the whoa to the point the feet remain anchored to the ground no matter the distraction. This is eventually proofed with bird work, where the dog is expected to stand flown birds, walking birds, birds under its nose, and so on. In this process, the whoa is managed with the long lead. Once the dog understands to stand birds, we begin the pointing process of having the dog find birds which are launched or flushed on the dog’s approach, instilling the idea that birds get away. Once the pointing we need is there, we begin the steadiness process leading into flushing and shooting the bird. It’s at this point the dog’s work has been overlaid onto the e-collar. The collar simply becomes an extension of the long lead. All of this work is proofed on wild game to help bridge the gap prior to hunting season.

With a dog that understands the system, we simply need to overlay our previous work onto the wild birds. Our training techniques depends on where the breakdown is occurring. A wild bird will always be a better teacher than us. They are uncatchable, and will familiarize your dog to wild game prior to the season. It will also provide you an opportunity to hone your training techniques to meet your dog where it will be come hunting season. When similar issues arise during hunting season, you will be ready with the right tool at the right moment, strategically bridging the gap from preseason to bird season.

Note that there’s a resting period we provide for wild birds in the spring. It’s important to provide a period of time where wild birds have the opportunity to rear their young. There is plenty of non-bird work that can be done around this time. It’s more important for these birds we love so much to have a chance to populate, especially on our training grounds and hunting covers.

Hunting season is a glorious time of year. Be patient with your dog and allow them time to study for their upcoming test on wild birds. Slow down and take in what our uplands have to offer. Your experiences in the outdoors with your family, friends, and your dog will tug at your heartstrings, forever calling to you until the next big adventure. Be a good teacher and guide your dog as it bridges the gap between training and hunting. Most importantly, enjoy the limited time that you have with your dog as you will never experience that level of love and loyalty anywhere else.

Jason Carter is a NAVHDA judge, NADKC member, director of youth development, secretary of NAVHDA’s youth committee, clinic leader and trainer at Merrymeeting Kennels. He has been around versatile hunting dogs his entire life, literally! Born into the Carter family and Merrymeeting Kennels, he attended his first NAVHDA test in Bowdoinham, Maine, when he was just a year of age. Jason successfully trains, tests and breeds Deutsch Kurzhaars in both the NAVHDA and NADKC testing systems. Through his work at the kennel, Jason has had the opportunity to develop pointers, flushers and retrievers over the years. When October arrives he can be found with family and friends hunting throughout New England.