Home » Hunting Dogs » The Evolution of the Pointer in America from the English Pointer

The Evolution of the Pointer in America from the English Pointer

Durrell Smith is a Georgia native, visual artist, wing shooter,…

Take a journey through the lineage and bloodlines that built the pointer in American as we know it today

In Part One, Creating the English Pointer from the Pointer Dog Ancestry, on the study of the evolution and development of the pointer dog and its predecessors, I concluded with a final thought stating, “The English Pointer is the definition of man’s unmistakable desire to manifest that which has lain dormant and untouched.” If we are to piggyback off that statement alone, it should be noted that the pointer as we know it in the United States has been a symbol of genetic excellence and persistent ambition. Our unmistakable desire, dormant and untouched, has been awakened and refined as the years of the 20th century chip away at the coals of rugged conformation, molding and pressing raw genetic material into the epitome of style, class, drive and intelligence. As the years flew by, departing from the late 1800s, the American ideal of a superior pointing dog manifested itself from the shores of the British Isles to the foothills and red clay of American soil.

The pointer itself is not coincidental, but rather the result of strategic breeding in an effort to accomplish a particular set of goals: to defeat the English setter in the field trials of America and to create a gun dog that could effectively cover the wider expanses of terrain and handle all forms of the native birds of the American continent. The earliest importations of pointer blood were not adequate to suit the environmental conditions of the American continent. The dogs were too large, too heavy-boned, and because of this there were a number of selective breedings that occurred which changed the conformation of the pointer in a very short amount of time–roughly over the span of 50-60 years.

This was also the reason why many of the earliest field trials differentiated contestants into weight classes. Dogs over 55 pounds were run against each other and dogs under were run accordingly. This distinction would later be broken up even further into the smaller, leaner, swifter, and fast pointers that we expect today.

I would like to note before diving into the study that this is not a full observation of all the pointers that make up our most notable dogs today. It is simply a glance at the some of the earliest dogs and their genetic traits which have contributed to the breed as a whole. It is an effort to find some of the common denominators that paved the way for notable National Champions and National Championship contestants. While I would love to run down the miles-long rabbit hole to uncover every pointer within the breed that made a great impact, in consideration of time and length it is simply impossible. This is only the beginning of my life’s work and just a chip off the tip of the glacier.

Earliest American history of pointer breeding: Price’s Champion Bang

The development of the pointer in America can be traced back to roughly 1850 when we consider the important patriarch of the pointer lines and break down the passage of the DNA on the X and Y chromosomes. The theory of chromosomal inheritance suggests that genetic traits are passed directly from father to son (y chromosomes) and there is a bit more genetic diversity on the mother-daughter side (x chromosomes).

Understanding this relationship will help identify the major players in the genetic pool within the earliest pointer breedings and how that affected future generations. Between the father and son we find a dog by the name of Champion Price’s Bang.

In 1871, Sam Price’s Bang was quite the knockout in field trials, starting in Shrewsbury winning third prize in the pointer puppy stakes, first prize in the pointer stakes of Devon and Cornwall trials, and winning his Champion title at the bench at the Plymouth Show. For three consecutive years after he continued to take first prize there.

Price’s Champion Bang would combine the smaller, leaner, and swifter qualities that were highly desirable from earlier pointer lines (Lang’s bloodlines) combined with the choice liver and white coloration. Champion Bang was a proponent stud, siring many winners. His offspring would go on to influence the American pointer as they were imported to America and bred with bitches that would be referred to as the Natives.

These Native dogs were already in America and were the desired bitches to be bred to Bang’s offspring due to their various unique qualities. It is from here we see the genetic diversity begins to reveal itself.

Offspring of Champion Bang: Bow, Beaufort, and Croxteth

We can see the impact of Price’s Champion Bang by observing many of his notable offspring and their impact as they were imported to America. Many of them were bred to prominent bitches as the selection was fairly limited during those early days.

Two of Bang’s sons, Button and Bow, out of Davey’s Luna, were brought over in 1878 by T.H. Scott from England. Stepping on American soil at four years old the dog, Bow, was noted to be in terrible condition. After being officially purchased by E.C. Stirling and turned over to the St. Louis Kennel Club, he was treated with cod liver oil and made a full recovery to return to the field.

Typical of many Bang descendants, he was of liver and white coloration and carried the old type head of the English pointers. As we look further back, the dog was also a descendant of Whitehouse’s Hamlet (previously discussed in Part One of this series). From Bow, we find Champion Bang’s grandson, Beaufort, out of Beaulah, one of the Native pointers of the time. Beaufort was considered most in fashion and one of the handsomest pointers of his day. We can safely say that many of the pointers of today go back to Price’s Champion Bang, although there were other sires who contributed to the progress of the American pointer bloodlines that we are familiar with today.

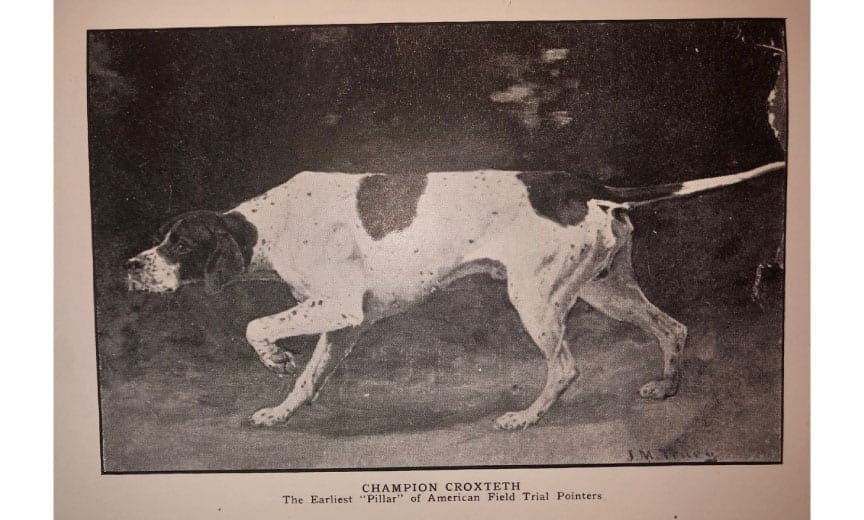

Of the other prominent sires, one who stood out was Croxeth, owned by Reverend J.C. MacDonna, coming to America in 1879. Sired by Price’s Bang, out of Jane, he was a large, strong-boned, liver and white dog with the unusual characteristic of a longer, leaner head in comparison to the more squared heads typical of the Sefton-bred pointers popular during the time.

Another of Croxteth’s unique physical attributes was his influence on the lighter-colored eyes of some pointers today and at the time. With these characteristics in mind and the success of his performances in field trials, it is no wonder that he would catch the public eye in the grand way that he did. He was quite the specialist of game birds, noted to be very intense of game, very fast and high-strung.

His arrival would mark the initial period of achievement for pointers in the American field trials. Having the greatest influence on the breed during the time, he would later be purchased by A.E. Godeffroy of Guymard, New York, and sired 12 field trial winners out of nine different bitches. Considering the selection within the gene pool, this was quite a remarkable feat.

The great matriarchs of the American pointer

Historical reference reveals that there were a small handful of dams that were influential in starting the various bloodlines of pointers that we are so fortunate to witness. Modern developments in breeding have continued the work of the earliest owners and breeders who realized that the passage of genetic material is most influential on the side of the dam and its X chromosomes.

Many of the traits we currently seek in great pointers can be attributed to the dam of a litter. Advancements in genetic analysis have led us further into the theory of sex-linked inheritance. The discovery of mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) has led to other analysis of the mDNA stating that, “Since the mDNA regulates the metabolism of the cell, it also determines the metabolism of the individual with practical applications to strength, speed, and stamina” (Bell, p.23). Although it was previously thought that the sire had the most influence on a litter, that sentiment would later be found untrue as geneticists would find more attributes in examining the relationships between the mother and daughters of a pedigree.

Of the limited offerings during the earliest days of breeding pointers in America, there are a handful of bitches that should be carried into memory as they offered the genetic prominence and diversity that was necessary for pointers to take the lead in winning championships and producing championship caliber bird dogs. The earliest distinct matriarchs predate Volume One of the Field Dog Stud Book records; thus we should start with the oldest and most influential matriarch that we will refer to as Nellie, who is known to have a number of alternative spellings and aliases throughout various kennel club documents.

Nellie has been found to have produced the highest percentage of National Championship contestants of all contributing dams within the breed. She was of the then popular Pape strain of pointers–solid black dogs bred by William Rochester Pape. Along with solid black, the Pape strain produced pointers of unusual colorations such as solid black with a white star on the chest and solid lemon dogs with white stockings. As of the 2015 record in the American Field, Nellie would go on to produce 21 dams holding a total of 25 Championship titles. It should be noted that she was the great matriarch of Champion Manitoba Rap, the first pointer to win the National Championship title in 1909.

Adding to the mix was the dam, Trinket, who produced nine dams with a total of 12 titles. It was noted that Trinket was bred to Croxteth several times to produce field trial winners. Trinket’s lineage would be responsible for notable National Champions such as Paladin (1951 & 1952), Whippoorwill’s Rebel (1987 & 1989), and Dunn’s Fearless Bud (1990) to name a few.

Third, we find the dam, Pearlstone, responsible for producing nine dams holding nine titles throughout their lineage. Pearlstone’s blood would show the likes of National Champion Comanche Frank (1914), Champion Lipan (1995), and Champion In The Shadow (2010) among many others. Pearlstone was also the earliest example of close breeding to Price’s Bang as she was the product of his son, Lord Downe’s Bang II out of Lloyd’s Hebe. Two of the top producing females, Pearl’s Dot and Dot’s Pearl (daughter and granddaughter) were the earliest top producers identified by anyone on record.

Next in line was the lemon and white dam Lily. Lily would be the Great Mother to a total of eight dams holding 10 titles. Lily’s lineage would later produce the three-time National Champion Becky Broomhill (1922, 1923, and 1925). Lily was bred by Edmund Orgill, known breeder of the Natives. Lily’s breeding with Flake could be considered the original meeting of the “blue bloods” with the Native pointers. Lily’s family would be the longest and most diverse but carried few landmark dams. From Lily’s bloodline we can also fast forward to find in it the 2007 National Champion Funseeker’s Rebel.

Out of the great matriarch, Bloomo, we see that she was the Great Mother of six dams holding six titles. Interestingly enough, Bloomo was a bit of an alien within the pointer strain, lacking in quality and symmetry, poor in conformation and not pleasing to look at yet quite the performer when turned loose in the field. She is the ancestor to National Champions The Arkansas Ranger (1958), Riggins White Knight (1968), and Red Water Rex (1969), again, only to name a few.

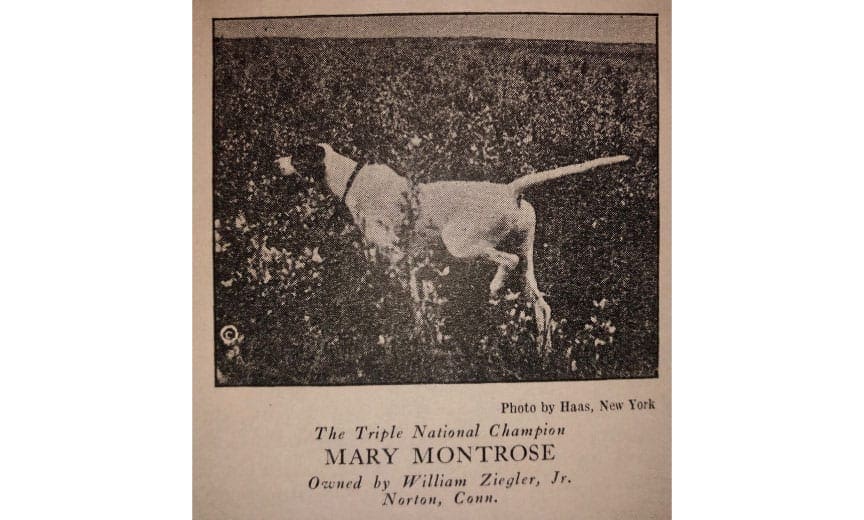

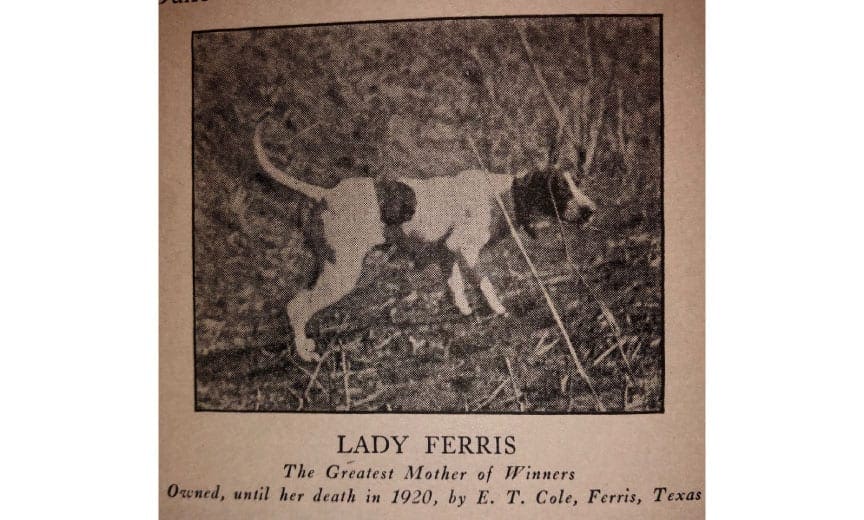

The matriarch, Jasmine, would produce four dams holding six titles, and the most notable offspring being Lady Ferris, an early field trial winner and the dam of triple National Champion Mary Montrose (1917, 1919 & 1920). National Champion Miss One Dot (1979) was also a product of the family of dogs.

Matriarch Westminster Rose, belonging to the Westminster Kennel Club, purchased in order to breed to Sensation, and another of the Natives, would produce four dams and four titles–most notably 1940 National Champions Lester’s Enjoys Wahoo, Safari in 1966 and most recently, Sparkle, the all time producing bitch responsible for National Champion Whippoorwill Justified. She was bred to the earliest of Price’s Bang offspring as they were imported into America.

Great Mother, Lee’s Grace, would produce two dams responsible for three titles. Little is traceable of the dogs from Lee’s Grace’s pedigree and she is likely related to another of the Great Matriarchs and traces to Native stock. Her most notable offspring are her daughter, National Champion Mary Blue (1929 & 1931) and Champion Norias Annie in 1934.

The remaining matriarchs are listed below:

- Faskally Belle – 2 dams, 3 titles

- Dainty – 2 dams, 2 titles

- Fanny L – 2 dams, 2 titles

- Hops – 2 dams, 2 titles

- Vanity – 1 dam, 1 title

- Queen Flush – 1 dam, 1 title

- Watson’s Nellie – 1 dam, 1 title

- Moonstone – 1 dam, 1 title

- Kate – 1 dam, 1 title

- Curfew – 1 dam, 1 title

**Note that a few of the dogs in the remainder of this list show no evidence that the line is still in existence today.**

History and genetics reveal so much more about the impact of the pointer’s importation to America that just could not be articulated in a single sitting. Our standards have blossomed exponentially since the dawn of the new wave of pointers setting foot on this side of the Pond. What is most impressive is the development of the original pointer dog and its standard on the bench and in the field in such a radically short amount of time.

In less than a century the pointer became America’s elite canine athlete and has excelled on the major field trial circuit along with hunters seeking to find enjoyment on a weekend in the piney woods or the prairies chasing the various elusive game birds. The accomplishments of the breed are still only a fraction of the overall picture. We as upland enthusiasts should not rest solely on the accomplishments of the dogs of old. We as field trialers, wingshooters, owners, and breeders can and should learn from the diligence of the earliest breeders and strive to continually advance the breed through careful analysis in both the conformation world and in performance.

It is a great responsibility that we have as aspiring dog men and women to continue to breed up, and it is my hope that this essay not just be seen as statistical or numeric jargon. As we move forward in our game bird pursuits, keep in mind that history shows that our breeds, especially the pointer, have been successful because of careful breeding and a love for the class dog world and an appreciation for their ambition in the field.

References:

Bell, Stephen. “A Survey of the National Championship Contestants.” The American Field, Dec. 2014, pp. 22–28.

Bell, Stephen. “A Survey of the National Championship Contestants Part Two: The Distaff Calculations.” The American Field, Dec. 2015, pp. 23–29.

Brown, William Francis., and Nash Buckingham. National Field Trial Champions: an Authentic and Detailed History of the National Field Trial Championship Association since Its Inception in 1896. Pointing Dog Classics, 1994.

Hochwalt, A. F. The Modern Pointer. 1923.

Hochwalt, A. F. Bird Dogs – Their History and Achievements. READ Books, 2017.

Durrell Smith is a Georgia native, visual artist, wing shooter, and dog handler. While creating compelling ink and watercolor illustrations based on his field experiences and hunting dogs, he also runs The Sporting Life Notebook and the Minority Outdoor Alliance. As a first generation hunter, Durrell seeks to learn and contribute to the community by connecting with visionaries and veterans within the bird dog community who are willing to share stories and knowledge about the various breeds, creating a bridge to welcome new and novice dog handlers to the gun dog community.

I see how the pointer has devolved here in America. Sadly, he has lost his identity for the most part. It started when we started putting too much emphasis on the wrong end of the dog.

In Europe, the European pointer retains his morphology. He has a distinct but more importantly FUNCTIONAL pointer head, a pointer body which supports his speedy gait and he/she looks like an English pointer when pointing.

Here in North America, most all dogs either parallel or are some aspect of a quasi-pointer. By this I mean that the pointer is THE most used breed to cross with a wide majority of other pointing breeds. So-much-so, that the descendants are neither their original strain NOR pointer. You can’t breed an Arabian to a mule and end up with a superior horse!

The conformation has been bastardized as well in terms of a “true” pointer’s gait, his stop and of course….that tail. Now…I’ve heard all about that high tail supporting the insinuation that you can find a standing pointer sooner because his tail stands up high in that tall grass. Funny, but when you put words to text, you see the absurdity, don’t you? In-other-words, the transition from the sacrosanct pointer to the American pointer is nothing more than something some individual(s) envisioned and then proceeded to impose/alter/butcher which contributes absolutely nothing to performance.

I challenge you in this regard: Take a black-and-white silhouette of a pointer then, take the same of a GSP but lengthen the tail of the GSP. What are the differences? Answer: Minuscule! In fact, you could do that for the Vizsla, Weim, shaved-Brittany, shaved Gordon, shaved GWP, etc. etc. here in North America – just add tail length. In Europe the pointer is a distinguishable, stand-alone breed unlike here in North America. It is unique – aside from conformation – in those formative ways that separated them from the other pointing breeds PRACTICALLY. No…? Take that black-and-white silhouette of a pointer’s head next to that of a GSP’s head. You could guess at best as to which is which – good luck. Not so, in Europe.

The gait of an “English” pointer sets it apart from other breeds based on functionality/application. Further-more, GSPs, Vizslas, Weims, Britts, GWPS, etc. separate themselves from pointers because they have an intentionally distinct alternate application. Here, we blended/mixed this with that, that with this and what have you got? Again, a sub-standard pointer and a bastardized _____! I get a kick out of all the predominantly white GWPs we’re seeing these days. Yeah….right….???

If you want a pointer, buy a pointer. If you don’t, you’re “skrood” here in North America because the odds support you might get a Britt that runs with relentless independence leaving his owner with a frustrated, perplexed, heart-rendering situation (which affects the whole family!) as to whether he should have bought a “Brittany” in the first place!

The reason for buying a not-pointer is because you aspire to have a not-pointer by way of it’s M.O. Good luck with that regardless of breed. And that is why there is a LARGE resurgence of imported dogs coming to North America. This brings to light yet another dynamic. Many European breeders are exporting their discards. Understandably so, when you look at our track record/past performance, lack of respect for tradition/origins here. We take non-pointers, then cross them into quasi-pointers!?!?! Why would anyone want to part with a breed of dog they have diligently tried to sustain, protect with centuries of sustaining it’s traditional form and function?!? I’ve said my piece and long after I’m done and gone, this offering WILL resurface, or at least the ideology most assuredly will, I’m sure.