Gordon Setter – Breed History, Standards and Origins

The Gordon Setter is a lesser-known hunting dog for upland game that originated in Scotland and continues to push forward today

Nathaniel Parker Willis was a famous American writer who counted Edgar Allen Poe and Charles Dickens among his friends. In 1827 he traveled to Scotland to visit Castle Gordon, the home of one of the most powerful families in Scotland and for whom the Gordon setter is named. In a letter published in the 1840s, Willis painted a vivid picture of his time spent there during the shooting season:

“The immense iron gate, surmounted by the Gordon arms; the handsome and spacious stone lodges on either side; the canonically fat porter, in white stockings and grey livery, lifting his hat as he swung open the massive portal, all bespoke the entrance to a noble residence.

“The Duke’s breed, both of setters and hounds, is celebrated throughout the kingdom. They occupy a spacious building in the centre of a wood, a quadrangle enclosing a court, and large enough for a respectable farm-house. The chief huntsman and his family, and perhaps a gamekeeper or two, lodge on the premises, and the dogs are divided by palings across the court.“

When Willis visited Castle Gordon in 1827, his host was George, the 5th Duke of Gordon. The ‘rare tan and black dog’ he mentions was eventually named after George’s father, Alexander, the 4th Duke of Gordon, who, at least according to some authors, is credited with creating the breed. But is it true? Was the Gordon setter really created at Castle Gordon?

The answer is, no. The castle’s inhabitants were certainly instrumental in the breed’s development, but there is ample evidence that black and tan setters existed long before the Duke of Gordon began breeding them.

READ: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing a Bird Dog – The Pointing Breeds

The true history of the Gordon setter

So where did black-and-tan setters, the ones that were eventually named Gordon, come from?

Dogs with black-and-tan and black-white-and-tan coats predate the various setter breeds. They occurred in the root stock of dogs imported from the continent that gave rise to the setters, so naturally they would appear from time to time as British breeders developed various strains of setters. At some point in the late 1700s and early 1800s some breeders began to select dogs specifically for a black-and-tan coat.

In Field and Fern, author Henry Hall Dixon wrote that “all the setters in the castle kennel are entirely black and white, with a little tan on the toes, muzzle, root of the tail, and round the eyes. The late Duke of Gordon liked it, as it was both gayer and not so difficult to back on the hill-side as the dark-coloured. The composite colour was produced by using black-and-tan dogs to black-and-white bitches.“

Edward Laverack, the father of the modern English setters, also visited Gordon Castle and viewed its strain of setters. “Two years after the death of Alexander Duke of Gordon I went to Gordon Castle purposely to see the breed of Setters. In an interview with Jubb, the keeper, he showed me three black-tans, the only ones left, and which I thought nothing of. Some years after, when I rented on lease the Cabrach shootings, Banffshire, belonging to the Duke of Richmond, adjoining Glenfiddich, where his Grace shot, I often saw Jubb and his Setters; then, and now, all the Gordon Castle Setters were black-white-and-tan.”

So why black? Other setter breeds are primarily red or white, and anyone who has ever hunted over a mainly white pointer or setter will admit that they are far easier to see in the field at distance. Yet for some reason, the Duke selected for black dogs. David Hudson, author of Working Pointers and Setters, explains why:

“. . . the Duke wanted things that way. He preferred his pointing dogs to be primarily black, and by judicious breeding he was able to produce the line that now perpetuates his name . . . Whim of fashion or personal choice? It really doesn’t matter. What is important, though, is the understanding that there were and are other reasons than simply pure efficiency in the shooting field that have dictated the development of gundogs over the past few hundred years.“

Over the years it has been suggested that the Duke crossed to other breeds of dogs get the black and tan coat we know today. Teasdale-Buckell wrote about a purported cross to bloodhounds in his book The Complete Shot:

” . . . Lord Rosslyn’s dogs had been crossed with the bloodhound to get nose, or so Bruce told the author. What it did get was colour—that is, a bright black-and-tan without white; whereas those dogs that were black-and-tan in the Lovat kennel had white feet and fronts, but a very large majority had body white as well.“

Others suggested that the colour came from a cross to a Collie, undertaken by the Duke of Gordon himself. A detailed account of what is purported to have happened was published in The Field:

“Some time about the year 1826 there was a celebrated sheep-dog belonging to a shepherd who lived far up on the Findhorn. Among her other accomplishments, the shepherd, being a bit of a poacher, had taught her to find grouse, for which she had a wonderful gift; she knew by a wave of the hand and a word whether grouse or sheep were wanted. When she had found grouse the shepherd would say a word or two to her in Gaelic, go down the hill for his gun, and on his return find the bitch still watching the grouse: it was more like watching than regular pointing; you might have fancied there were sheep in front of her to be looked after. The Duke of Gordon (then Marquis of Huntly) heard of this bitch, and begged her of the shepherd. The shepherd unwillingly gave her to the ‘Cock of the North.’ The marquis put her to one of his best setters, and some of her first litter were black-and-tan. She herself was long, low, rather smooth for a collie, and black with very light tan.”

Of course many authorities were sceptical, but some did concede that a cross to a Collie may have happened. Rev. Thomas Pearce (Idstone) wrote:

“I do not give implicit credence to the story from first to last. The Duke may have tried the experiment, but I do not believe that he stained the pedigree of his whole kennel. I have seen, nevertheless, many Collie dogs which would pass muster for coarse Gordons, and Gordons which might easily be mistaken by a Gaelic shepherd for his Sheep Dog; and the Collie, or teapot-tail, occurs occasionally in the very best and most authentic strains which trace directly to the duke’s breed.”

Others were more adamant in their refusal to believe that the duke would ‘contaminate’ his line with Collie blood. In The Dogs of Scotland, Thomas Gray quotes a certain ‘Mac’:

“The collie cross I cannot for a moment entertain, for no sportsmen would ever think of doing such a thing, because it would spoil a dog’s ranging qualities, and dog of this cross would have a tendency to run with their noses too low; a collie finds by the foot scent, a setter that would do so would be a complete failure.”

Reverend Thomas Pearce thought that the Duke must have crossed Irish Setters into his line at some point writing:

“ . . . for in every litter, provided it descends from his kennel, there are a brace or more of red setters. These have the peculiarity of being almost white until they moult their setter coat, when they take the brilliant mahogany red, and follow the form and have the noiseless panther gallop of the Irish setter.”

James Watson on the other hand discounts the idea, writing that a cross to Irish Setters would have been extremely difficult at the time.

“No, we will have to discard the Irish suggestion altogether and stick to the line of least resistance, which is, that when he sent south for greyhounds or cattle he got what setter crosses he wanted. His man would have to ride on horseback as the easiest mode of travel and the dogs or animals would have to walk. Yet Irish setter crosses are glibly talked about as if all that had to be done was to telephone or telegraph to Ireland to send over an Irish setter by express and look for it at the railway station the next day.“

In more modern times, there have been rumors of unofficial crosses to Irish and English Setters. American field trial lines are usually singled out as having been modified by such crosses.

The Gordon setter in America

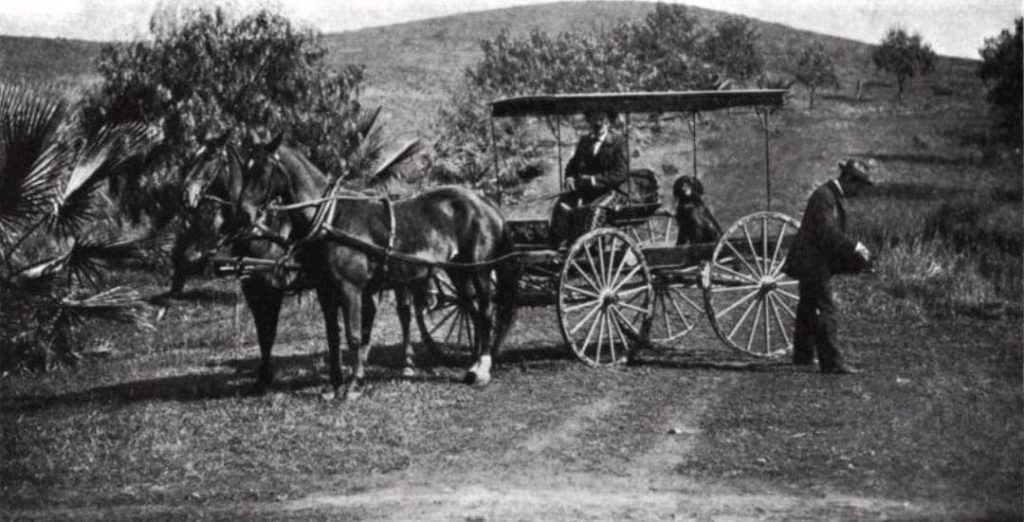

The first Gordon setters to arrive in America were imported from Scotland by American Secretary of State Daniel Webster as a favor to his friend George Blunt. In 1874, Blunt wrote a letter to Forest and Stream describing how and when the dogs came to America and his experiences with the breed since that time.

“In December 1839, I received a note from Mr. Webster, who had arrived from England, stating that he had a brace of Duke of Gordon setters for me, which I found on board the London packet John Griswold’s line. The dog was named Rake, and the bitch Rachel. The pair were the handsomest I ever saw—gentle and intelligent, with most acute powers of scent.“

The first registered Gordon in the U.S. was “Bang” born in 1875 and registered in 1879. In 1891, Henry Malcom formed the Gordon Setter Club of America and in 1892 the AKC recognized the breed. In 1924, the BKC changed its club name from Black & Tan Setters to Gordons.

In the early years, Gordons met with some success in field trials and bench shows. They were well regarded by hunters and in some regions a relatively popular gundog. But by the end of the 1950s, there were very few breeders selecting dogs for their abilities in the field. Most Gordons were bred for dog shows, not for hunting. By the late 60s most of the field Gordons were gone. Thankfully a few dedicated breeders, and in particular, Suzanne and Norman Sorby, the founders of Springset Gordon Setters, hung on. By carefully line-breeding dogs from their predecessor, Alec V. Laurence, they succeeded in producing a dominant line of field-bred Gordons that went on to win field trial, bench show and even dual championships. Today it is estimated that over 90 percent of field bred Gordons in North America are related to the Springset line.

Dan Voss, an American owner, breeder, field trialer and judge of Gordon setters, said that the late Norm Sorbie “took a breed on the brink of extinction and raised it to a whole new level. He was a trainer and dedicated field trialer who bred very tightly within his own line producing over 6-7 thousand dogs in his lifetime. His dogs had a racier build, were smaller, faster, and had a much bigger range than other Gordons. You can’t overstate what he did. Without Norm, there would be no hunting Gordons today.

Considering a Gordon setter? Here is the breed’s modern overview

Gordon setter health issues

Like all dog breeds, Gordons are not exempt from health issues. A recent survey of Gordon owners and breeders identified hip dysplasia, cancer and bloat as the most common concerns. But there are also other breed-specific issues such as cerebellar cortical abiotrophy (CCA), a hereditary neurological disease found only in Gordon setters (and possibly Kerry blue terriers) affecting muscles and coordination.

In Norway it was discovered that 9 percent of Gordons suffer from an autoimmune disease found in other breeds called symmetrical onychomadesis which causes the dogs’ claws to slough off over a period of about three months. When the claws grow back, they are unusually brittle and misshapen.

Gordon setter populations

In terms of population, the history of the Gordon setter is marked by periods of growth followed by years of decline, then renewed interest, an increase in numbers, followed by yet another period of decline, and so on.

In the U.K., the high point in terms of registration numbers was in the early 1900s. But, like all breeds, two world wars had a devastating effect and rebuilding the British population took longer than the other setter breeds. Currently only around 250 Gordons are registered with the Kennel Club each year, and many of those are from show lines. Yet, despite the low numbers, the British continue to produce some outstanding dogs that can hold their own in all-breed field trials.

In the U.S. during the 1880s and 90s, fewer than 100 Gordons were registered, on average, each year. Numbers remained low until after World War 2. The 1950s and 60s saw steady growth for the breed with numbers peaking in 1974 when nearly 1400 Gordons were registered. The 1990s were a time of precipitous decline in registrations, a trend that continued into the 21st century. Currently (2020), approximately 350 Gordons are registered with the AKC each year.

In Europe, the Gordon has solid bases of support in some countries. In France for example, nearly 600 Gordons are registered each year and in Norway about 550. However no matter where they are bred or how many there are, Gordon setters from lines bred mainly for dog shows are in the majority. In some regions, the ratio of show-bred to field-bred is close to 50:50 but in others like the U.S. and U.K., there are probably 10 show-bred Gordons for every one field-bred dog.

Form and function of the Gordon setter

Throughout the history of the breed, the ideal size, weight and overall build of the Gordon setter has been the subject of debate. As far back as the 1870s, Gordons appeared to have been of two types. Teasdale Buckell wrote that “one lot were light-made, active dogs, and the other, including the descendants of Rev. T. Pearce’s Kent and those of Lord Rosslyn’s blood, were very heavy in formation.“

A trend towards larger, heavier dogs in the show ring was not isolated to Britain. Harry Malcolm, then president of the American Gordon Setter Club wrote in 1891 that “the Gordon Setter in America is called, by the opposition, all the hard names they can think of because some men who breed dogs simply for show, breed them to a size that utterly unfits them for field-work.”

Reverend Pearce wrote that “He is far too heavy—I am writing of the common type observable at our shows—and he must be refined at any cost. How all this lumber and substance accumulated I cannot say.“

Voss says that in America today the breed is “made up of various sized dogs, from 90 pound males to 30 pound females, if you include both show lines and field bred lines. If you focus only on field lines, a big dog would be 60 pounds, and the corresponding female from field lines would be considered large at 50 pounds.

Coat and color of the Gordon setter

All modern standards for the Gordon setter state that the only officially recognized and accepted colour combination for the breed is black and tan. Dogs that are anything other than black and tan are disqualified in the show ring and anything more than a small patch of white on the chest is not allowed. However, in the past, and occasionally today, other colours occur in the breed. In Dogs of Scotland, D.J. Thomson Gray wrote:

“Let us hark back seventy years (from 1891), and we find one of the most famous kennels of setters in the kingdom of Gordon Castle. These dogs were of different colors, the majority being black and tan and black, white and tan. Some were liver and white and black and white, and lemon and white was sometimes seen. . . . The black, white and tans were heavily marked, black and white with tan spots above the eyes and on the cheeks—the black and white clearly defined, but not ticked or spotted, but for what reason I don’t know, and the head and ears stood by black.

“The black-and-tans were of a lighter tan than the black-and-tans of to-day, and very often had white breasts and white feet. . . . As to the original color, I had it from an old man named ‘Bill’ Roger (who was about the kennel at Gordon Castle before the battle of Waterloo) that the dogs were of the several colors that I have already mentioned, and my opinion is that the setters were of no particular color.“

If the setters were of no particular color in the beginning, by the time the Duke’s dogs were auctioned off in 1836, most were either black-and-white or black-white and tan. Today, the breed standard only accepts black-and-tan coats. However, other colours can and do pop up from time to time in purebred Gordon litters. Perhaps the most common non-traditional colour is solid red. Gordons with white-and-black coats also occur. One of the greatest U.K. field trial champions in breed history had a mainly white coat with black-and=tan.

Liver (brown)-and-tan coats are the result of a combination of recessive genes inherited from both parents. It is unknown where the recessive gene came from, but like the genes for a red coat, it has probably been in the breed from the very beginning. Vero Shaw mentioned liver-and-tan coats in his book The Dog, stating that “The black-and-tan Setter has unquestionably been crossed with the Irish, probably to improve the brilliancy of the tan. Hence the appearance in many litters of Gordons of liver-coloured whelps. It is also noticeable in the reputed pedigree of Old Kent . . . the great-grandfather of that famous dog was a liver-and-tan dog belonging to Sir Matthew Ridley.”

Coat length and texture varies as well, mainly between show lines and field-bred lines. Voss notes, “There are dogs that have been bred for generations as show dogs, with coats dripping to the ground. There are lines of field dogs that seldom need to have a clipper applied to them. Maybe the top knot needs to be cleaned up now and again.“

Field search and point

Like every other aspect of the Gordon, speed and range have varied over time and between lines and even regions. In its homeland, there were times in the early days when Gordons were considered to be just as fast and wide ranging as the other setters, and times when it was expected to be closer working and slower. In the U.S., similar variations occurred throughout the breed’s development. Today, Gordon Setters from field-bred lines are fast, dynamic workers in the field search that range relatively widely. However, true big-running all-age dogs are extremely rare in the breed.

Voss observed, “Big running dogs are in the minority. There have been a very few all-age Gordons like one of my dogs, five times national champion Buck. He was among the biggest running Gordons of all time, but we don’t need all Gordons to run like him. The breed standard mentions that the Gordon’s range should be comfortable, and not many folks want the really big running dogs. They cover the ground with an attractive, smooth, elegant gallop, head held high. Their tail is not as active as other setters, and most of them over here point with a high tail. Gordons typically have a strong point that develops relatively early, but there are some that may lack point. Some are natural backers, but overall needs some improvement.“

Retrieving abilities of the Gordon setter

Historically, the Gordon, like all the other setter breeds was not expected to retrieve in field trials in the U.K., but many American hunters and breeders in the early days did use their dogs to fetch game. In the past, the Gordon Setter Club even ran field trial stakes with a retrieving component in the past, but they were dropped years ago. So some Gordons are natural retrievers but many are not. That said, a few have done well in NAVHDA tests, proving that they can get excellent retrievers if well trained.

Water work with Gordon setters

Dan Voss observes, “Some folks duck hunt with them, but it’s been my experience that the retrieving instinct is not as strong in them and needs to be developed. Tracking is not really in the breed’s profile or nature.“

Gordon setter character

All the Gordon owners and breeders I’ve spoken to agree that Gordons are generally friendly dogs with a decent on/off switch, are easy to live with and tend to be good with other dogs. Cindy Findley, a hunter, amateur trainer and field trialer that owns Gordon, Irish and English setters said:

“Of all my setters, the Gordons that I have are absolutely the most intense on bird scent. All great pointing dogs are usually intense on point, and I’m fortunate that I enjoy staunch solid points on all my dogs. But when the Gordons are in the scent cone, it is almost as though they are on the brink of life or death. Trembling, chattering teeth, and strings of drool are indications of their minds being totally consumed by the scent. And while the English and Irish may be aware that you are approaching, I’m not sure that the Gordons aren’t so focused that for a few seconds they are on a higher plane of existence—a dimension that only a few dogs ever achieve.”

Training Gordon setters

When I asked Dan Voss about training a Gordon he said, only half jokingly, “If you make a mistake with a Gordon you will be apologizing for a long time. Some want to do things their own way, and as soon as you put on any pressure they can sulk. Others are easy going and didn’t hold a grudge. So the best approach is to use the West/Gibbons method where the bird is the cue. Take your time, go easy, and you will have a great dog.”

Craig Koshyk’s take on the Gordon setter

The Gordon setter has never been the most popular setter, or the fastest, or the widest running of the setter breeds. But it is certainly among the most admired, both for its beauty and abilities in the field. When I asked Voss about how and where to get a good one he said, “There are some spectacular bird dogs in the breed, and a number of dogs that won’t make the grade.You have to do your research. In North America there are only about a half dozen breeders of field trial and hunting lines and their waiting lists can be long.”

When I asked Cindy Findley who should consider getting a Gordon to hunt with she replied, “The breed is an ideal choice for hunters who have a deep appreciation for the skills and ELEGANCE needed by pointing dogs. And for hunters that are looking for an absolutely dedicated hunting PARTNER, not just a dog. I have often said that a Gordon is for a hunter who enjoys a hunt, and equally enjoys spending time on the tailgate, pulling a few burs from their partners ears, while enjoying something brown to drink and watching a contented setting sun.”

Wonderful story. I currently have 2 Springset Gordons. And they are truly Partners in the field and at home.

Best article I have read on the breed. Thank you so much! Wouldn’t be without our family Gordon ( our first ever family dog, no involvement in hunting but domiciled very rurally). Long and ranging daily off leads are good for us all; being our hen ‘monitor’ (on the right side of the fence of course!) is a job he takes extremely seriously and assures plenty of stimulus and trembling. He is the most loving, committed family member that you could ever hope for. Why don’t more people want a Gordon, we always ask? Catherine, UK

One aspect as to why Gordon Setters are not preferred by many upland game bird hunters is the chief aspect behind why I love them so. The psyche of the Gordon is such that they tend to not thrive while being treated as an employee. They need the solid certainty of being in an unquestioned, almost mystical, partnership with their owner. They are truly a personal gun dog and will try to move heaven and earth to please the person with whom they are bonded, to the exclusion of all others. They bond fanatically. If someone, God forbid, sells or gives away a Gordon after the dog has bonded to them, the dog will never be the same; something will die forever inside the Gordon’s mind.

Springset Gordon Setter Kennel is very much alive today run by Norm’s daughter Laura Borges in Eagle Point, Oregon–carrying on Norm’s legacy. http://www.springset.com

I have had four Springset Gordons. Two were excellent for duck and goose hunting. One retrieved a goose cripple, still quite alive. They would bring a waterfowl to shore near me. All were excellent in the field and would bring a bird close to me as if to say “the rest is up to you stupid”. I only gave them basic obedience training. The Springset line did the rest.

Good history on the Gordon. You might add that setters of all types were kept and owned by Castle breeders in Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales. The lords interbred dogs with each other. You failed to mention Lord Lovat/Fraser who shot with the Duke of Gordon. Lord Lovat had an excellent line of Black, White and Tan setters that was used by the Duke of Gordon to get his favorite Black, White, and Tans. This same line of Lord Lovat’s is found in the Duke Robe cross by Lewellen. As you stated most of the Duke of Gordon’s dogs were black, white and tan. Laverack points this information out that I just stated. I owned a setter from Russ Guevel of Melrose Gordon Setters. His name I gave him was of course Duke. Duke was great dog with a powerful nose. He had been hunted on quail and other birds. He however did not know what a woodcock was and would flush the birds. Ignorance on my part of not knowing he did not know what they were led to a complaint to another hunting friend about his dastardly deed of flushing. The friend exclaimed the next time he flushes one shoot it for him! Not wanting to shoot a non-pointed bird I got to thinking maybe the friend was correct. Needless to say, I did just that and shot one for him. He now became a pointing woodcock hunting fool! Also, by the way he was a bird retrieving machine.