Home » Hunting Dogs » Edward Laverack: the Father of the English Setter

Edward Laverack: the Father of the English Setter

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

The life and times of Edward Laverack, the man renowned for remodeling the English Setter, provides a fascinating insight into the breed’s history and legacy.

“Suddenly into the middle of the coterie of breeders a bombshell was flung, so startling as to cause a violent upheaval of all the old theories, and a complete revolution in setter breeding, the effects of which have lasted to the present day.” —Walter Baxendale

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

Walter Baxendale’s “bombshell” was a man named Edward Laverack, now universally regarded as the father of the modern English Setter. Little is known about his early life, but as a young man, Laverack was apparently a shoemaker’s apprentice, but where he worked and for whom is not clear. According to Robert Armstrong in All Setters, Laverack “spent his youth in Hawick, a town in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, but at the age of 17, not liking it after he had been there some time, he ran away.”

Edward Laverack’s Early Life

| Born | 1800, grew up in Hawick, Scotland |

| Died | April 4, 1877 in his home, Broughall Cottage |

| Appearance | Short, stout, cherry-faced, gentlemanly |

| Marriage | Mary Dawson, wife. Born in 1819 and died in 1862 |

| Starting Setters | Old Moll (F) and Ponto (M), or a male from Sir F. Graham’s strain |

| Laverack Setter Qualities | Hard-headed, incredibly staunch, high head carriage, an improved nose, a tendency to bolt, perpetually in motion |

| Publications | The Setter (1872) |

In his book The Setter, Laverack himself wrote that he had been shooting in the highlands of Scotland “ever since was eighteen years of age” and that he had “rented shootings for the last forty-seven years.” Since Laverack was in his early 70s when he wrote the book, that would mean he had been shooting on the moors since he was in his mid-20s. This would seem to tally with Amy Fernandez’s claim that Laverack left the shoemaking trade at age 25 after an unexpected inheritance abruptly revised his career plans.

In any case, we can assume that by the 1820s, Laverack must have had the money to not only rent shooting rights on moors owned by the likes of the Earl of Carlisle and the Earl of Southesk but to purchase a brace of setters from one of the best strains in the land. Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean he was rich. On the contrary, when Laverack was a young man, rates for shooting rights and the price of dogs were relatively low.

In his mid-30s, Laverack seems to have settled down a bit. Census records seem to indicate that in 1835, he married Mary Dawson, then just 16 years old. In 1840, the couple welcomed their only child, a boy. Sadly, the child died at age three. Then, just as Laverack was beginning to make his mark as a breeder, he lost his wife Mary, who died in 1862 at the age of 41.

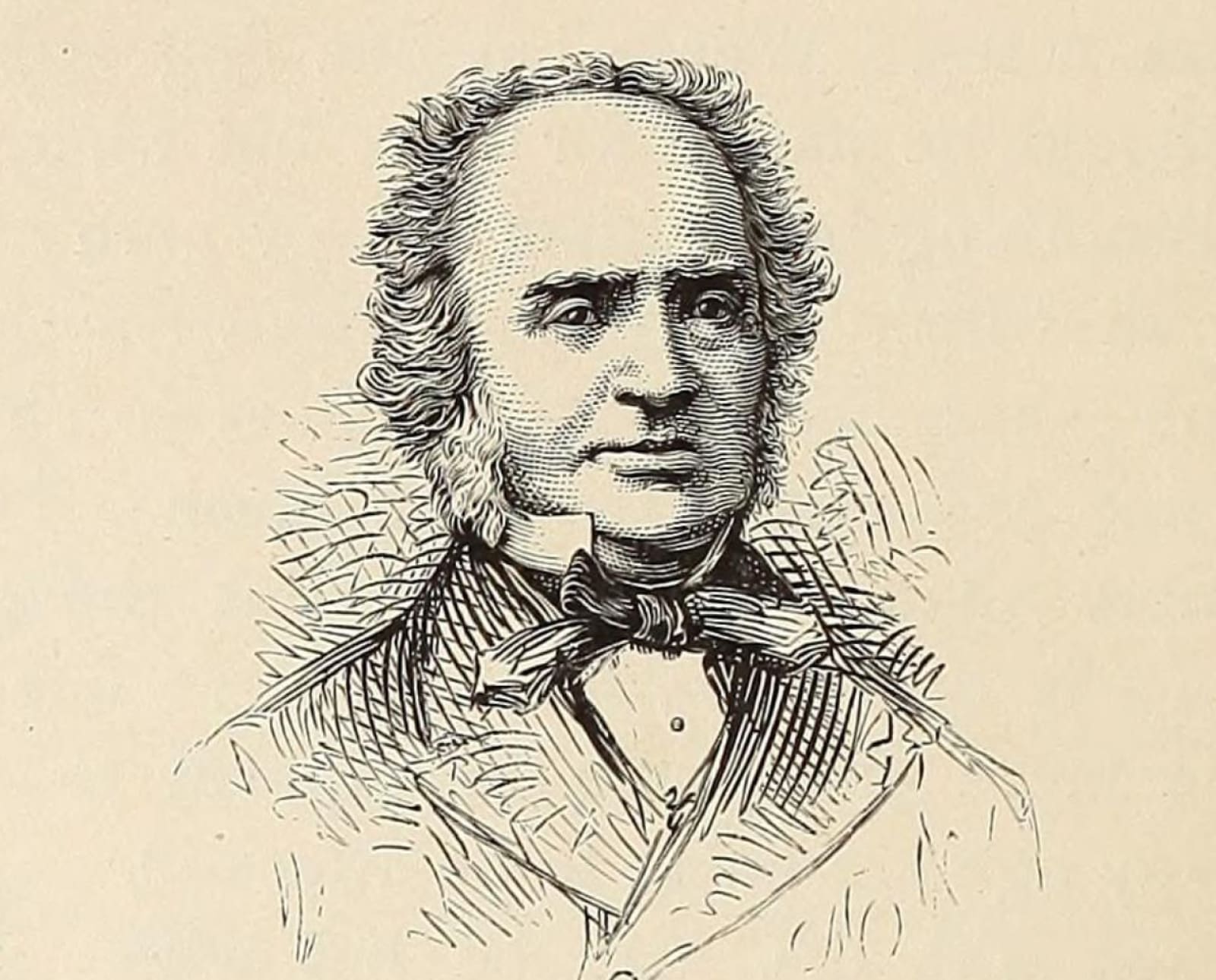

Not many photos of Laverack exist, and only a few written descriptions are found in the old literature. Perhaps the best was written by L. H. Smith, who met Laverack in the 1870s at a dog show in London. Smith wrote that he was a “short, stout, cherry-faced old gentleman, who looked exactly like what he was–a contented, retired tradesman.”

Laverack’s Setters

Laverack’s claim to fame was, of course, his setters. Here, in his own words, is the origin story of his line, which he said started with a female named Old Moll and a male named Ponto. Watson wrote in The Dog Book that “it would seem fair to assume that he did not get her (Old Moll) as a puppy, but probably obtained both as developed shooting dogs.

Laverack’s account regarding the origins of his first two setters has been repeated ad infinitum since it appeared in his book. However, after his death, evidence came to light that suggested it may not have been entirely accurate. For example, in May of 1882, Stonehenge, then editor of The Field, wrote in “Laverack Setter Pedigrees”:

. . . it is doubtful whether Mr Laverack’s memory served him correctly, for we have recently heard from Sir Frederick Graham that Mr Laverack bought his original setter bitch from Mr. Connell, banker of Carlisle, for £8 8s., and, crossing her with his (Sir F. Graham’s) strain, formed his breed.

In the following issue of the same magazine, Edward Armstrong, the son of a close friend of Laverack’s, corroborated Frederick Graham’s statement in All Setters.

Sir Frederick Graham is perfectly right when he says that Mr. Connel’s Moll was bought by Mr. Laverack for £8 8s., and he might have added, too, that she was bought through my poor old father’s recommendations.

In the 1930s, Edward Armstrong’s son Robert went even further. He claimed that his grandfather, old Armstrong himself, sold the dog to Laverack, stating, “The first dog he ever owned he bought from my grandfather. She was a setter bitch called Moll.”

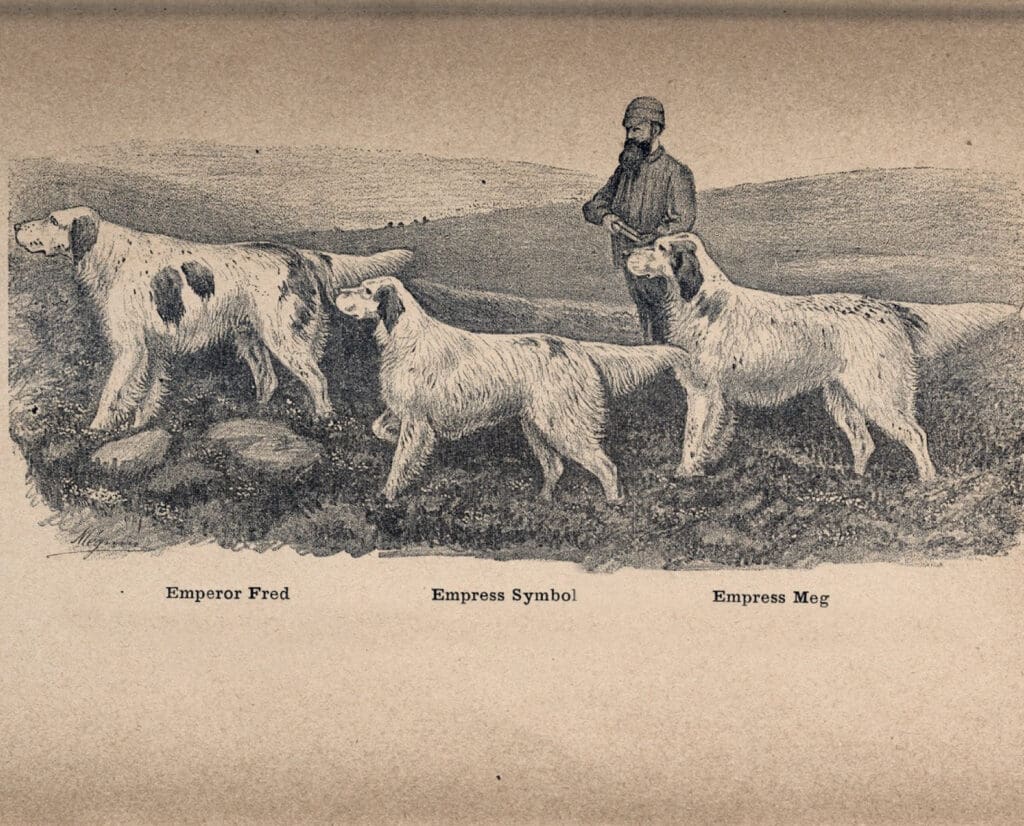

Despite the uncertainties surrounding the origins of Laverack’s original stock and how he subsequently bred from them, by the time his dogs became known to the wider public, they showed a remarkable uniformity in their conformation. Stonehenge wrote in Dog in Health that they were:

. . . of all colors with a white ground, some being white and red, some white and blue, some white and black, and others again white, black, and tan. Latterly the blue Belton (a thickly ticked white and black) was the prevailing color, but even with these a whole litter never appeared alike. His celebrated “Countess” was of this color, but her brother and sister were black and white in large patches.

As for how they hunted, Baxendale described them as “fast and keen rangers, excelling in high head carriage, and of indomitable spirit. In fact, one of the charges laid against them by their critics was that they were practically unbreakable.” Others also wrote about how wild and hard-headed Laverack’s dogs were. But this didn’t bother Laverack himself.

This combination of incredible drive and staunchness on point was illustrated in an anecdote related by Drury in British Dogs:

The writer recollects Laverack himself being once asked on the moors with respect to a dog of his, which was endued with perpetual motion, entire self-hunting, and utter regardlessness of whistle, “However do you get that dog home at night?” “Why, sir, I just wait till he points, and then I put a collar and chain on him and lead him home.”

Laverack spent several decades developing his own strain of setters in the north of England and Scotland. His dogs found favor among some of the most prominent sportsmen of the day in England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Even Queen Victoria may have seen some of his dogs at work when she was staying in Inveraray, Scotland. And, as growing numbers of sportsmen from across England traveled north on newly developed rail lines to shoot over bird dogs, they too may have come in contact with the man and his dogs.

Laverack, Late In Life

By the time dog shows and field trials were first organized, Laverack was an old man. Yet despite his age, he managed to make up two show champions. Others did even better with dogs from his kennel. In fact, until the early 1890s almost every English setter to earn the title of show champion had Laverack’s dogs in its background. While most agreed that Laverack’s dogs were quite good, some, like Stonehenge, thought other men had dogs that were just as good, if not better.

In any case, it wasn’t really a question of how good or good-looking Laverack’s dogs were—even his most strident critics conceded that they were among the best in the land. What really caught the attention of the canine establishment, and ignited a furious debate in the sporting press, was the incredible claim Laverack made about the pedigrees of his dogs.

Walter Baxendale explained in Millais’ Gun at Home:

The bombshell that fluttered the dovecotes of the setter men was Mr. Laverack’s statement that these wonderful dogs had been bred by him, during the forty years since he had the breed, from two specimens only, viz., Ponto and Old Moll. Soon after he published his pedigrees, and these showed the most extraordinary amount of inbreeding—inbreeding to an extent hitherto unheard of. Apparently, the system he had been adopting ran dead against all the canons of breeding animals hitherto held as axioms by breeders of any description of animal; yet here were the results before their eyes, in the shape of dogs showing none of the defects hitherto by common consent laid to the door of inbreeding, even to a far less degree.

On the contrary, the dogs he showed were above the average in substance, size, and stamina, looking the sportsman’s dogs all over, and, as subsequent events proved, possessing speed, nose, stamina, and indomitable endurance far beyond the generality.

All this was a violent upheaval of orthodox ideas, and for a long time following the heated controversies, degenerating in some cases into acrimonious personalities, between the champions of the rival camps—the progressives, on one hand, those that ranged themselves on the orthodox side on the other—proved what an epoch was the arrival of Mr. Laverack with his dogs and his pedigrees.

Few men excited more controversy, or wrath and animosity, from the vested interests which his dogs upset. His story as to the descent of his dogs from two specimens met with much incredulity, and for years in and out of the Press discussion waxed warm between partisans on opposite sides. The eminence of the Laverack was not recognized in all quarters when Mr Laverack first appeared, or if it was, jealousy hindered justice being done to its merits. Owners of the black-and-tans, at that time the fashionable breed, did not care for these rivals and possible conquerors, and it became the fashion in and out of the Press to snub Laverack and his dogs. This tirade was headed by “Idstone.”

A champion for Mr. Laverack, however, came forward in the person of Mr. Llewellin, and directly challenged “Idstone” (the Rev. T. Pearce) to back his criticisms on the Laveracks and of Laverack by meeting him to run a match with a brace of his Gordon Setters against a brace of Laveracks. “Idstone” was far too astute to accept the challenge, and if he had done so, his Gordons would have been second best in an endurance test against the little Laverack bitches Countess and Nellie. As Countess was, in her day, a bitch without a rival.

Since we know so little about his early life and his final years, it would be easy to conclude that Laverack spent most of his time breeding dogs and defending himself in the court of public opinion. However, it is important to remember that Laverack was, above all, a keen sportsman who spent decades on the moors shooting over gun dogs.

It wasn’t until he was an old man that he became famous, and with fame came both praise and scorn, as it so often does. Some considered him a genius who had accomplished the seemingly impossible. Others, as noted in The Armstrong Setter, considered him an outright fraud:

Mr. Laverack, at that time, was beset by such a combination of enemies as never sought the destruction of a single victim. A clique was writing and talking up certain breeds of dogs, and Mr. Laverack, who browbeat them at every meeting and stated his convictions fearlessly in all parties, was detested and abhorred by them. No man ever met with more opposition than he did; yet he triumphed over all his enemies. I am very sorry, too, that certain of these enemies carry their hatred beyond the precincts of the grave, and abuse the old man yet.

The controversy peaked after Laverack’s death in 1877, when a formal complaint was lodged with the Kennel Club by none other than Purcell Lewellin, the man to whom Laverack dedicated his book. However, Llewellin’s goal was not to besmirch Laverack’s reputation. Instead, he wanted to warn others about Laverack’s supposed ‘in and in’ inbreeding system. In his complaint, according to Grinnell’s “Laverack Pedigrees,” Llewellin wrote:

The whole system of inbreeding now beginning to be so much practiced, to the detriment of pointers and setters and other breeds of animals, will once and for all be proved to have no favorable precedent when once the pedigree of Pride of the Border has been brought to light.

John A. Doyle, a Kennel Club member who sat on the committee adjudicating the case, agreed with Llewellin according to Burges’ American Kennel:

It must be remembered that this theory has been used not merely to explain how good setters had been bred in the past, but how they ought to be bred in the future. I hold that the inquiry instituted by Mr. Llewellin, and the evidence adduced by him, has disposed of that theory and all that depends on it.

I will resist the urge to recount the details of how Laverack’s pedigrees were eventually found to be unreliable. All that we can say is that Laverack’s pedigrees seem to contain some rather severe discrepancies. For example, he sometimes listed different parents for the same dog or claimed certain bitches whelped litters at ages that strained credulity. Yet despite the flaws in his recordkeeping and memory, the pedigrees Laverack published were far more detailed and extensive than any others of the time. That may have been part of the problem.

The final years of Laverack’s life were not happy ones. He endured the slings and arrows of his many detractors and struggled to keep alive the strain of dogs he had spent his life developing. When Edward Laverack died in 1877, only five setters remained in his kennel: Blue Prince, Blue Rock, Cora, Blue Belle, and Nellie or Blue Cora.

Today, Laverack is generally considered to be the most important figure in English Setter history. His influence on the breed cannot be overstated. His dogs formed the foundation of almost all modern setter lines around the world, and his book not only served as the basis for the creation of the modern English Setter standard but was the first to describe many of the various strains of setters being bred by sportsmen in Britain and Ireland before the modern era. However, Laverack and his dogs also had some negative effects on the breed. Their dominance of the show ring attracted untold numbers of people to breeding, many of them lacking the experience and judgment necessary to make wise breeding decisions. The dogs’ massive drive and sometimes headstrong nature often proved too much for the average sportsman.

Laverack died on April 4th, 1877. Many years later, a monument was erected at his gravesite, next to the small church in the Village of Ash near Whitchurch, England. The engraving reads:

To the memory of Edward Laverack, born 1800; died 1877 at Broughall Cottage. This monument is erected by admirers in England and America. His great love for the lower animals made him many friends. He was specially fond of dogs and by careful selection remodeled the English Setter, the best of which are known by his name.

Some years after Laverack’s death at his house, then called Broughill Cottage, was purchased by Herbert Lushington Storey, a well-known philanthropist from Lancaster. During the First World War, it was converted into a Voluntary Aid Detachment Hospital with 20 beds for soldiers wounded at the front. Today the house is still there, renamed Ashdale House. The current owners breed world-class show horses.

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.