Home » Hunting Dogs » Understanding the Stages of Steady Training a Dog

Understanding the Stages of Steady Training a Dog

Jason Carter is a NAVHDA judge, NADKC member, director of…

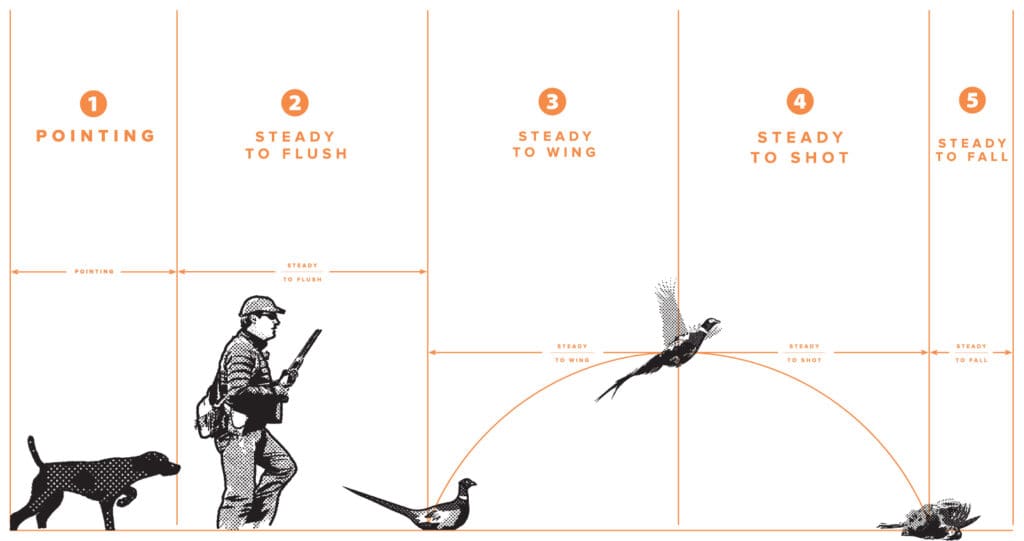

Steadiness training can be broken down into four phases: steady to flush, steady to wing, steady to shot, and steady to fall. Here, we explore the dynamics of each learning stage for a pointing dog.

During 2023’s opening weekend of bird hunting, I ran into a gentleman enjoying a day in the field with his two-year-old Brittany. He was one of those quirky Mainer types with that Downeast accent and a dry sense of humor, complemented by a razor-sharp wit. I asked him how his hunt was going, and he replied, “Wicked good, I’m tellin’ ya!”

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

“Have you seen lots of birds?” I asked.

“A few, but my dog’s seen plenty,” he quipped, squinting one eye with a sideways smirk.

“Are you having some steadiness issues?” I asked.

“Yesah, something awful bub. Rippin birds like it’s his job.” After investigating further, he explained to me that his dog was competing with him for the birds and would charge in at first acknowledgment of his approach. We spoke for a bit longer, and I gave him a few ideas that would hopefully allow him some shooting opportunities later in the day.

With a handshake and some pleasantries, we went on our way. What stuck with me from our brief interaction was that a bird dog, at a minimum, must be steady enough to allow you to move ahead of it to have any success in the field.

A dog that will stand still no matter what temptation is placed before it is considered to be a steady dog. Synonymous terminology you may have heard would be “broke” or “staunch,” both describing a statue-like dog that will not move during the flush, wing, shot, or fall of the bird until commanded to do otherwise. Having a steady dog allows a unique experience reserved only for those willing to put in the time. Whether you are testing your dog or hunting it, owning a steady gundog will guarantee endless safe and productive adventures.

To be fair, I’ve hunted over a good many “meat dogs” that are only steady to flush, or long enough for us to get ahead of it, and have provided us with just as many birds. There is absolutely nothing wrong with training a dog to only be steady to flush if that’s your goal. It’s really about your personal preference. However, if you plan on taking a youth out or a novice hunter, I’d argue that a steady dog is what you want. It provides a much safer hunting experience. Keeping the dog behind the gun allows us to focus on the bird with one less variable to worry about.

Growing up, I was told bird dogs should remain anchored to the ground until commanded to retrieve. That was the goal, at least. We worked hard all summer long to attain that goal. During hunting season, when our focus shifted from training to wild birds, we tended to lose some ground in steadiness. However, the understanding was there to easily reel our dogs in when needed. As my father would say, “All dogs are liars and cheaters waiting for the right opportunity to get what they want.”

Dogs that have been trained to hold point until the handler arrives will do so partly due to it being cooperative. However, this is mostly due to the dog fearing that if it moves, the bird will fly away. Steadiness comes into play once the dog realizes the presence of its handler. Before initiating the steadiness process, you would have hopefully provided your dog with a hunting season filled with copious amounts of wild bird exposure.

Wild bird contacts are unequivocally the best experience you can provide any developing hunting dog. These experiences bolster its drive to find game, its understanding of how to find and handle birds, and provide a foundation in steadiness before you start putting on the controls. I encourage every and all opportunities to get your dog on wild birds no matter where you are in your steadiness process. It introduces the dog to game, and the bird will teach the dog manners. This provides dogs with a deeper understanding that birds can’t be caught. This will strengthen your point and avoid the early-season dog imbalances that most hunters experience.

Introducing Steadiness Training

Before attempting to steady up your dog, you must first have a dog willing to stand point. Pointing is separate from steadiness, as pointing should naturally occur in pointing dog breeds. This innate behavior causes the dog to pause before it pounces to catch the bird. The point happens before the dog is aware of the handler. It’s purely a relationship between the bird and the dog. Our job is to foster this relationship in the absence of our influence. Flying the bird on the dog’s approach or movements strengthens and elongates the point over time. Only when the dog is holding point for an extended period of time do we begin the steadiness process.

Next, it will be important that your dog has completed a collar conditioning program where the dog understands there is no end to your line of control. Ideally, this process systematically teaches the dog that the collar’s stimulation means much more than just recall, or returning to you.

At times, dogs with a lot of drive tend to push out too far in pursuit of game. This inspires some handlers to seek control at a distance through the use of an e-collar. If used exclusively for this purpose, the collar will cue the dog to return, no matter what the situation is. This can become problematic; it could teach the dog to come off birds, or worse, believe that the correction is coming from the bird. Without a proper collar conditioning program, the collar could elicit fear around birds and steal the hunt from the dog. However, with proper understanding and use, the e-collar can be an invaluable tool that reinforces the understanding you worked so hard to develop.

The scope and sequence of your steadiness program need to systematically lead your dog toward your steadiness end goal. However, it’s your dog’s obedience foundation that provides the tools necessary to get you there, and you will need this foundation before beginning steadiness training. The dog will need to understand how to keep still, go away from you, and how to come back. The stronger the obedience, the easier your dog will progress through its steadiness training.

Steadiness can be broken down into four phases: steady to flush, wing, shot, and fall. Each phase of steadiness builds upon the learning of the previous to create a comprehensive understanding to remain stationary from the moment the bird is located until commanded to retrieve or hunt on. Let’s dissect each of these categories to glean a more comprehensive understanding of what steadiness is all about.

Steady to Flush

Steady to flush is the process of teaching your dog to accept you as a teammate and provider, not a competitor for the bird. I call this “allowing you in.” Dogs often perceive you as the reason they lose the bird, so they will charge in, or “break,” preventing you from denying or stealing the bird from it. It is your job to teach your dog manners around game through the flushing steadiness process.

Training flushing steadiness may take some time. Rushing it will only be detrimental. Handlers should allow themselves ample time to prepare their dog before hunting season. Remember, each lesson should progress the dog’s steadiness. It doesn’t need to be perfect; just progress.

If your training is successful, your dog is now showing more and more self-control, resisting the temptation to break. As the dog solidifies its point, it will allow you to approach, touch it, and even move past it towards the bird. The dog has accepted your leadership and your steadiness to flush rules, which means it’s time to start heading towards steady to wing.

Steady to Wing

Steady to wing is the process of teaching your dog to remain frozen in place upon the flight of the bird. For most dogs, a flying bird triggers a predatory instinct to chase and capture. For this reason, it’s of great importance to use good flying birds to avoid teaching the dog that birds can be caught.

For the most part, the bird teaches the dog to hold point, not you. With young dogs, verbal commands are essentially useless as they are normally not heard by the dog in its excitement to chase. Asking a dog to remain in place can be challenging. As the bird lifts off, a dog with self-control will remain still while marking the bird solely by turning its head. If it’s too much too soon, it will move its body in the direction of the bird or even attempt to catch it.

Allowing the dog to move at all is a slippery slope that may lead to it taking out the bird. For young dogs, chasing the flight of a bird is a normal developmental reaction. In fact, it’s something we encourage to help develop drive. However, for mature dogs, it’s your job to deny any catch attempts by launching the bird, restraining the dog with a long lead, or both.

Dogs find it far easier to remain still if the bird stays still on the ground or flies within sight. It’s when the bird is up and walking or disappears behind a tree or hill in flight that tends to trigger the chase. This is more of an issue for trained retrievers because getting that bird in its mouth is paramount. You may also notice that the closer the bird is to the dog, the more tempting it becomes to break. Lastly, dogs that encounter wild birds tend to be far more driven to point and then chase. Wild birds add another level of stimulation for the dog to deal with.

As your dog develops its steadiness to wing, it will settle when the bird takes flight. Initially, you may see some steps or hops due to over-excitement. In time, this will dissipate. Your dog will get to the point where it can stand still at the flight of the bird, no matter the species or direction of flight. Remember, it takes good flying birds to make a bird dog, so don’t skimp on wild bird exposure.

When your dog remains glued to the ground regardless of whether the bird flies over its head or between its legs, you know the dog is ready to start the steady-to-shot training process.

Steady to Shot

A dog that stands still at the shot is considered to be steady to shot. A shotgun blast can create a startle response or excitement level within the dog, triggering it to chase the bird. Hopefully, once the dog puts it together that the gun provides the retrieve reward as long as it remains steady, your approach will help anchor the dog. On the shot, at best, the dog will flinch as if to catch the bird. If it’s too much too soon, the dog will crash in and take out the bird. These are normal developmental reactions. It’s your job to control the dog, denying it any catch opportunities, and if it does break, returning the dog to its pointing position. After the dog demonstrates success, you can add more temptations, including multiple birds, shots, and gunners.

It’s important the dog has gone through a gun acclimation or neutralization process prior to using a gun in proximity to any developmental hunting dog. The dog must understand the shot is connected to something positive before you use it to steady up the dog. Sensitive dogs can become fearful of the shot and will run from birds to avoid exposing themselves to the shot blast. To avoid this debilitating issue, be sure to treat every dog as if they are gun-sensitive when introducing gunfire.

When the dog realizes the gunshot equates to putting birds in its mouth, there will be an initial spike in drive and likely a loss of steadiness for a little while. Denying the dog this retrieving opportunity is very important. It’s only when the dog is willing to religiously stand still until after the shot is fired do we progress to the final phase of the steadiness process: steady to fall.

Steady to Fall

A shot bird is exciting for both hunters and dogs. This is the moment everyone has been working so hard to see. The steadiest of dogs will be chomping at the bit to get the retrieve if trained to do so. The dog may take it upon itself to self-release, or break, so that it can finally get what wants: a bird in its mouth. For pheasant hunters, self-releasing dogs are preferable to help deny a crippled pheasant the opportunity to escape. However, the break denies the hunter an opportunity to reload for late fliers and risks bumping (running over) other birds on the way to the bird.

The retrieve must be earned by remaining still until the dog is released for the retrieve. If allowed to break on the fall, you risk losing steadiness earlier and earlier in the steadiness sequence. After the bird has been shot and the dog marks the fall, there should be a notable pause before you release the dog. Alternatively, walk up to the dog’s side before sending it for the retrieve. The idea is to develop emotional restraint and solidify the steadiness before providing its reward.

Once your dog is steady to fall, you have graduated to the final phase of proofing your work.

Proofing Your Steadiness Training

Dogs learn situational expectations. In other words, the learning that happens in your backyard doesn’t necessarily mean your dog will translate it into new environments with different variables. For example, a bomb-proof steady dog at home may become a takeout artist a mile’s drive up the road. This happens because you haven’t proofed the dog, or exposed it to many new places. Currently, your dog’s understanding is that the steadiness rules only apply to your backyard. Teaching consistency through repetitive training in new environments with new variables improves your dog’s working intelligence. This is something that should be introduced during training and finished on the hunt. In fact, much of what a hunting dog needs to learn must be taught in hunting environments.

Once your dog is steady on captive birds, proof your work on wild game or well-liberated captive birds. Before hunting season, I like to train on wild birds using a blank pistol to bring into light any holes in my dog’s steadiness training. If this isn’t possible in your state, try changing things up a bit to get the dog excited. The idea is to find holes in your training and deal with them while they are emotionally charged in a fixed environment versus during a hunt. Running the dog in trials, on new training grounds, or running in braces can fire the dog up or bring out its competitive nature to help reveal steadiness issues.

Proofing isn’t necessarily making your dog unsteady but rather challenging it in a way that tempts the dog to make mistakes. These mistakes can then be corrected in a controlled environment. If this needs to happen during hunting season, so be it. It’s not the end of the world if you forgo a few birds to steady up your dog.

Having a dog steadied up to where it will stand the flush, wing, shot, and fall may seem to be a bit unrealistic or unnecessary until you have experienced it. If you get the opportunity to feel what it’s like to hunt over a steady dog, you’ll find yourself dreaming of having one of your own. The calm and relaxed nature of the hunt allows you to slow down and take in the full experience. A handler who is confident and secure in the dog’s work has the luxury of knowing where the dog will be when a shooting opportunity presents itself. The joy that comes with high-level teamwork and trust between you and your dog grabs ahold of your soul, making your upland experience even more enjoyable.

Steadiness Categories:

- Steady to Flush – The dog remains steady until the handler puts the bird into the air.

- Steady to Wing – The dog remains steady while the bird is in the air.

- Steady to Shot – The dog remains steady after the shot is fired.

- Steady to Fall – The dog remains steady after the bird hits the ground and until the handler commands it to retrieve.

(NAVHDA Aims and Rules Publication)

Training Principles:

- Strive for improvement in each lesson, not perfection.

- Keep it positive. Fieldwork should be filled with affirmation and praise and be an enjoyable experience for the dog.

- Avoid over-training. End every session while the dog still wants more.

- Keep sessions short and successful with consistent repetitions.

- Use variable rewards, such as touch, food, praise, flown birds, and play retrieves.

- Keep quiet. When working steadiness on birds minimize any existential vocalizations until the dog is released for the retrieve. Only talk when you have something to say. Streamline your commands and provide limited quiet affirmations when appropriate.

- A bird dog’s single mission in life is to get that bird in its mouth. It will be your job to shape the dog’s steadiness in a way that eventually allows the dog this opportunity.

Jason Carter is a NAVHDA judge, NADKC member, director of youth development, secretary of NAVHDA’s youth committee, clinic leader and trainer at Merrymeeting Kennels. He has been around versatile hunting dogs his entire life, literally! Born into the Carter family and Merrymeeting Kennels, he attended his first NAVHDA test in Bowdoinham, Maine, when he was just a year of age. Jason successfully trains, tests and breeds Deutsch Kurzhaars in both the NAVHDA and NADKC testing systems. Through his work at the kennel, Jason has had the opportunity to develop pointers, flushers and retrievers over the years. When October arrives he can be found with family and friends hunting throughout New England.