Home » Hunting Dogs » Creating the English Pointer from the Pointer Dog Ancestry

Creating the English Pointer from the Pointer Dog Ancestry

Durrell Smith is a Georgia native, visual artist, wing shooter,…

A look at the history and development of the English pointer from the pointer dog

In an effort to better understand the development and prevalence of our current achievements in the contemporary world of pointing dog breeds, it is imperative that we reach back into the complex history of what is recognized as a foundation breed to our most beloved wingshooting lifestyle and field trial sport. Historians recognize the English setter and English pointer as the most effective points of entry into the modern pursuit of wild and liberated game birds.

In this essay I hope to outline the earlier highlights of the propagation as best as possible within a three part series. There have been a number of literary documents from essays, to articles, to hard and soft bound books that have attempted to record and illustrate the best attributes of the English pointer. None, however, are more notable than three works by William Arkwright and A.F. Hochwalt that I wish to cite and reference in support of my lifelong pursuit to study, admire, and harness the traits of my favorite breed, the pointer—a dog mistaken for its English forefather, similar in some ways, but altogether a by-product of man’s manipulation of the English subject at hand.

It is my hope that by the end of this series we as a gun dog community will have a much clearer definition of what differentiates both animals from the other, and provide an understanding of their ancestral network as a whole.

A “start with the end in mind” approach may help in better understanding the rise of the English pointer. The pointers of England at the time were a manifestation of successful efforts of their pioneer breeders who capitalized on the very few shortcomings of the English setter, which during the 1800s, dominated the rapidly growing field trial scene.

Initially, Spanish pointer dogs brought into England were too slow and heavy boned for the English sportsmen. It was the goal of the owners of the early English pointers to improve their dogs in order to build a more complete breed that would be a competitor, if not a winner, on the trial scene.

From A to B: the Aviarii and the Braque

Humans have engaged with a pointer-like dog since Roman times. In the antiquity of Gaius Sallust Crispus through Pliny the Elder, historians have revealed early anecdotes of Romans who, after war, had taken from Spain dogs called “aviarii” and introduced them to France and Italy. Noted by Arkwright who revealed the passage in the Paginas de Caza by Evero, “When the sagacious animal approached the quail or other sluggish bird, he appears to fascinate it by his flashing glance; meanwhile the fowler, now with a kind of cage, now by spreading a net over, gets possession of his prize.” The description was always one in question, but confirms that a dog of similar repute has always been native to the Spanish landscape and had been imported through Europe from there.

The origins have met with skepticism with the narratives being then told by German author H. Francken in 1754 to the French author M. Castillon d’Aspet in 1874. I’m confident in saying that the lack of a truly accurate historiography left much in question regarding how these dogs were classified in the times before the Middle Ages. We do know that hunting dogs of various types were prevalent, but little had been written of a dedicated pointing dog.

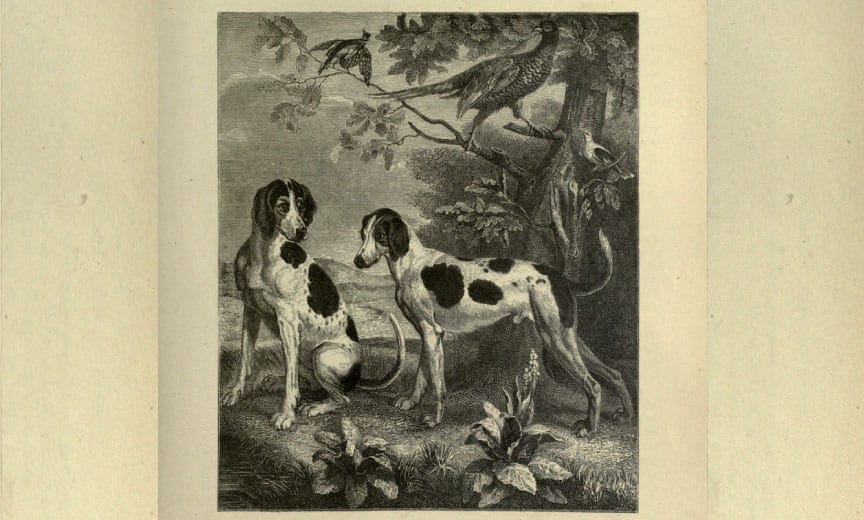

The earliest known recordings of the braque, an early ancestor of the English pointer, date back to Spain and France, with roots tracing back to Italy in the 1300s. The famous painter, Vittore Pisano (or Pisanello) sketched the faint white head of a pointing-dog. It evidenced a light colored profile with a flesh colored nostril and orange eye.

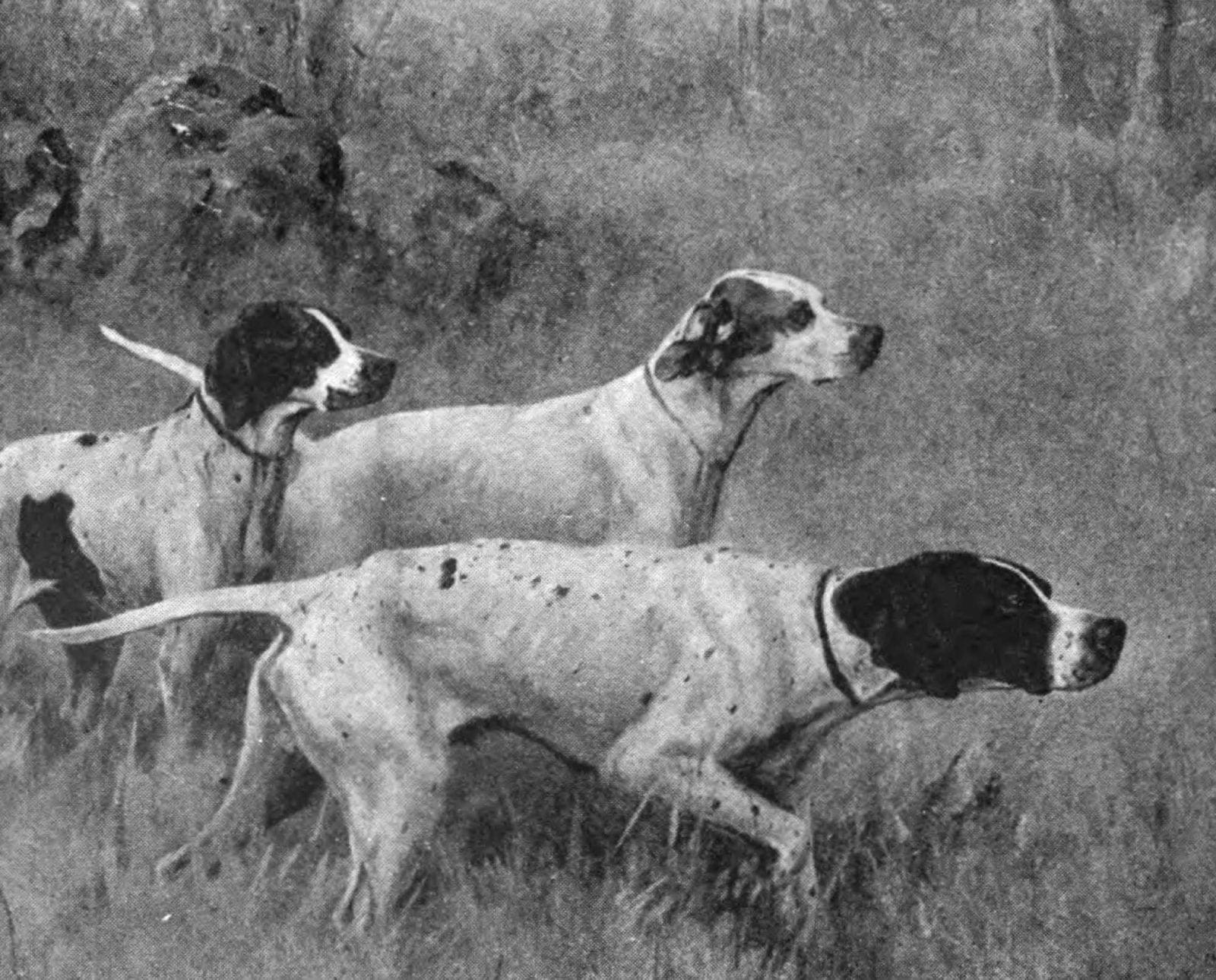

Titian of the Venetian School (1477-1576) followed with a painting of two dogs of “pointer character” (Arkwright, Plate III). The braque, during the earliest times before the English pointer, was a dog of antiquity and the word was used to classify both hounds and pointing dogs. Imported from Spain to France, and then to England, the braque would later be solely attributed to the imported pointing dogs alone.

Quite frankly, I paid little attention to old English vernacular in grade school. I would have been a more attentive student if my teacher had informed me that even Shakespeare referenced those ancestors in his “The Taming of the Shrew.” It seems that the earliest setting style dogs were in high favor during Shakespearean times, as well as those who preferred the pointing trait instead—a contrast not unfamiliar to today’s dog fanciers. Spadoni, around 1673, stated that:

“The brachs that point (bracchi da ferma) should be spotted and dappled with bright tawny, and have large ears, long muzzle, black nose, feet spurred (spronati), hind legs well bent, and tail fine. To make use of them with the gun, it is necessary that these dogs be steady on point, nor ever flush the game that they have found, so that the sportsman, by carefully circling round his dog with arquebus before the game is sprung, may obtain a shot” (Arkwright, p.53)

The tradition of high-class dogs in the most vain sense held true throughout the dogs’ European travels. Maintaining kennels with only the best of the breed was typical among the British aristocracy, with large estates being available to only those of noble birth. With no middle class, England was split between the haves and the have-nots, and the haves surely had an interest in a finer species. Canine stud books were kept private by the owners and no public stud book was in consideration during those times. Yet owners would observe the next man’s dog and the two would breed their dogs if the traits were desirable and coins aplenty.

Hochwalt notes that “English breeders, unlike Americans, were as careful in the matings of their dogs as they were of their horses . . . ” (p.16). Notably, the pioneer sires of these English pointer lines started with four main stakeholders: Brockton’s Bounce, Statter’s Major, Whitehouse’s Hamlet, and Garth’s Drake. Their blood and pedigrees were well kept, exacting, and heavily guarded long before the advent of any formalized pedigree system. The men responsible for these dogs are noted below:

• Thomas Webb Edge • George John Legh & son George Cornwell Legh of High Legh Cheshire • J.C. Atrobus of Eaton Hall • Lorn Combermere • Sir Vincent Corbet (importer of Spanish Dogs) • W. Statham of Derby • Thos. Statter the Earl of Sefton • Lord Derby • Sir Richard Garth • Mr. Whitehouse, breeder of Whitehouse’s Hamlet • London gunmaker J. Lang • George Moore of Appleby • Mr. Bird & Mr. Gilbert • J. H. Salter • R.J. Lloyd Price of Rhiwlas • S. Price of Devonshire • Mr. Lort

***It is noted that there were others to come later***

Braque to Brockton’s Bounce

Breeders of the day placed a significant amount of interest in the Edge dogs, particularly the descendant of that kennel by the name of Brockton’s Bounce, a monolith in pioneering the English pointer strains. Bounce’s notoriety was prolific on the public field trial scene in England in 1865. He would be best remembered as one of the first great performers and a highly potent producer whose offspring were also highly regarded and carried many similar physical and hunting attributes.

Major ecstacies of Statter’s Major

It is true that Statter’s Major was highly celebrated because of his pedigree, and today he would be any pedigree hound’s greatest joy. Statter’s Major was considered one of the most valuable pointers in his day, and his conformation standing as tall as his reputation. He was a dog that could be traced back to when the pointers made their first entry into Spain, something which proved that he was a guaranteed truly purebred dog.

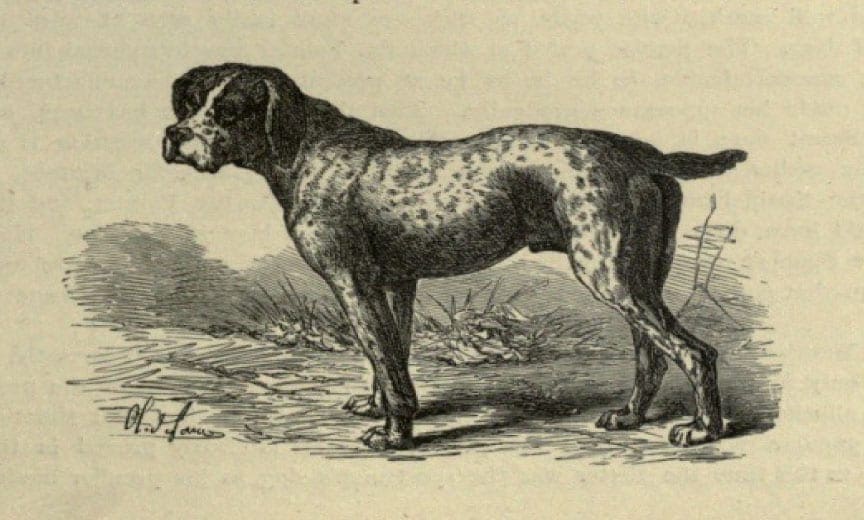

Fast and diligent to the task at hand, Statter’s Major was a dog that could be handled almost anywhere although his conformation would later become his downfall. Though true to type, he was true to the old-type English pointer stature—handsome, large in stature and heavy boned. Yet he could not keep up with the growing demands of range and pace required of top dogs in the growing field trial venues. By today’s standard we look for a more modest dog with great range and style, but Statter’s Major was sure to be the first English dog with an abundance of traceable blood in his background.

Lemon and Whitehouse’s Hamlet

There is a familiar interest from your author in the lemon and white dogs within the pointer pedigrees. It seems as though there was a small following of breeders and owners interested in this coloration. Before the era of field trials, lemon and white dogs were not in vogue. With the rise of field trials came a particular interest in a dog that was seen to be agile, clean-cut, and very attractive; these were shown against the darker Major and Bounce varieties.

There were specific arrangements made by Whitehouse who always strove to maintain the purest blood in England. Whitehouse dogs were known to be able to withstand any amount of work and behaved better under a consistent hunting program. Hamlet was known to be built powerful yet light, although visibly very “beefy.” On the bench scene, he was a proven winner, and as a trial dog, sire to many champions. It can be said that Whitehouse’s Hamlet was a great contributor to the foundations of field trial dog conformation.

Garth’s Drake

Bred by Sir Richard Garth, Drake was thought to be superior to any other pointer or setter of the time with regard to speed, handling, and bird manners. According to author Stonehenge, Drake “on account of his marvelous speed . . . invariably dropped to his points in order to stop himself in time, otherwise he would have run over his game. It was not until in later life—his seventh season, in fact—that he began to assume a standing position on point” (Hochwalt, p.24).

Although the dogs in the latter years of England’s field trial origins would commonly move at much higher speeds, dogs moving at that pace were far more exceptional than the norm. This set him apart from the much larger, slower dogs that came before. Drake became notable in the field and was considered a great producer not because of his owner’s ability to market and advertise his dog’s capabilities, but through the dog’s own honest merits and achievements. He was a great athlete that changed the race and standards of race and range in the field trials subsequent to his time in the field.

Beyond modernity of the English Pointer

Beyond the earliest histories of these dogs came many great contributors to the English and American strains of the pointer breed. But what is important to understand is the reverence that both hunters and pointer aficionados have held in regard to pointer-dogs since the earliest of times. The efforts to breed better and more efficient dogs for the hunt and competitive interests have elevated the overall prowess of what was once a rough mold of a dog indigenous to the European continent.

The English pointer is the definition of man’s unmistakable desire to manifest that which has lain dormant and untouched. The efforts would lead your author into a second study moving across the pond to examine the pointer, one of our earliest American bird dog icons. It is my hope that I can continue to document the continued histories of the Pointer breed’s matriculation through the 21st century.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION for FREE : Google | Apple | Spotify

References:

Arkwright, William. The Pointer and His Predecessors: an Illustrated History of the Pointing Dog from the Earliest Times. Skyhorse Publishing, 2015.

Hochwalt, A. F. The Modern Pointer. 1923.

Hochwalt, A. F. Bird Dogs, Their History and Achievements. Sportmans Digest, 1922.

Durrell Smith is a Georgia native, visual artist, wing shooter, and dog handler. While creating compelling ink and watercolor illustrations based on his field experiences and hunting dogs, he also runs The Sporting Life Notebook and the Minority Outdoor Alliance. As a first generation hunter, Durrell seeks to learn and contribute to the community by connecting with visionaries and veterans within the bird dog community who are willing to share stories and knowledge about the various breeds, creating a bridge to welcome new and novice dog handlers to the gun dog community.

Have issues with the history that is claimed in these two books. I did buy the first book! If it is for a picture book? It’s an amazing book! If it is for actual far from the truth. In Spain the have extremely old writings survived the civil war. And even older books in England that places the Perdiguero de Burgos decades before the GSP. There is actual documentation that states the Burgos was the baseline of the GSP. The timeline in the first book is incorrect. William Arkwright book The pointer and his predecessors is a good book. But it is not the Bible of the pointing breed! It itself is subjective to question. Given the timeline and language barrier. If one seeks the truth of the pointer it will take decades of search from the birth place of the pointer. Which everyone knows is Spain.