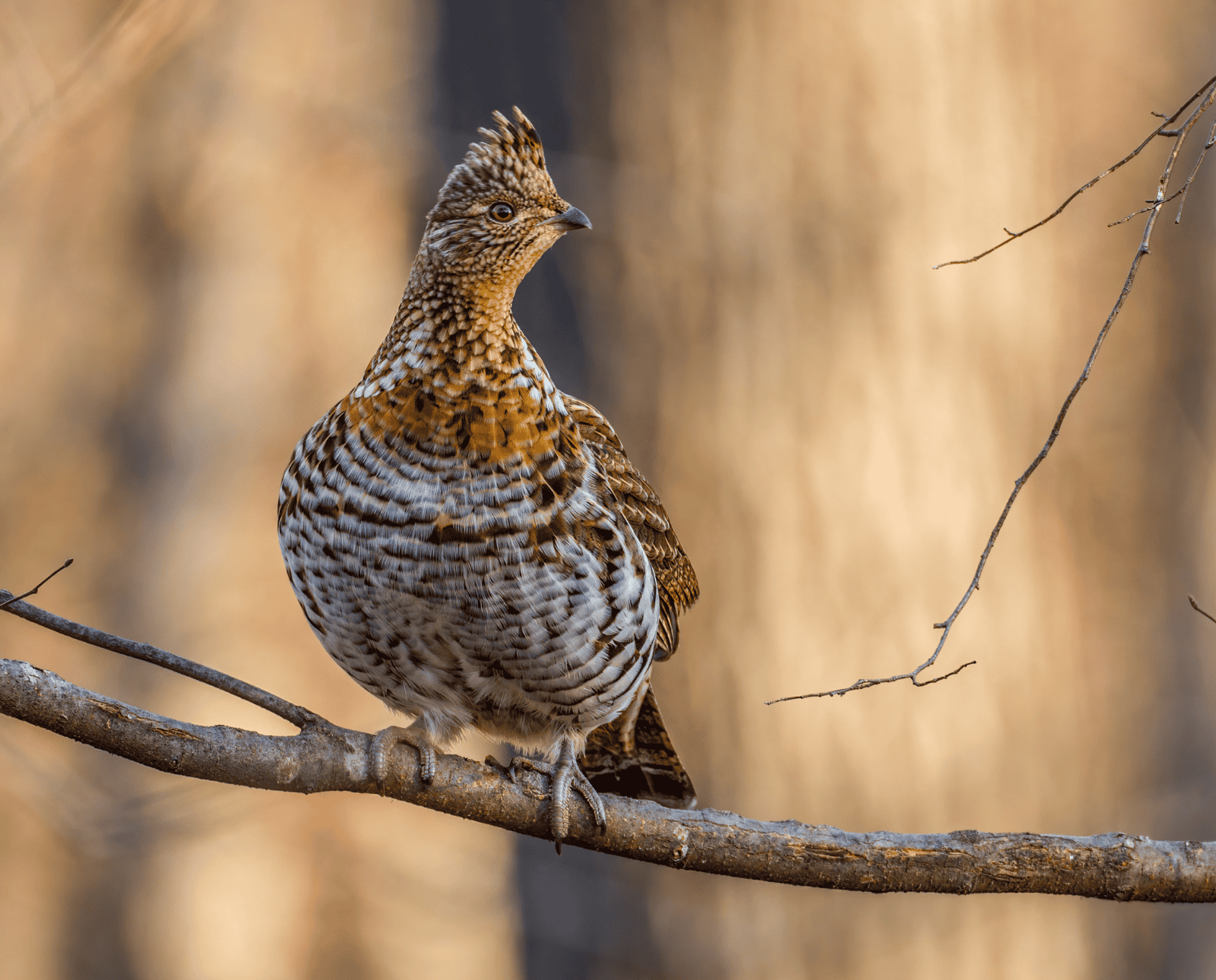

Home » Grouse Species » Ruffed Grouse Hunting » What’s Limiting Eastern Ruffed Grouse Populations?

What’s Limiting Eastern Ruffed Grouse Populations?

Gary recently retired as Forest Game Project Leader with the…

Insights from a career grouse biologist on the factors impacting eastern ruffed grouse survival.

As an aspiring wildlife biologist, I was extremely fortunate to spend a semester of my undergraduate studies in an internship program with Mr. William K. (Bill) Igo, a biologist with the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources (WVDNR). Among the many influences Bill had on my life was his passion for upland game bird biology, management, and hunting.

Bill and his Brittany gave me a great introduction to ruffed grouse hunting. He sensed my interest and gave me a copy of The Upland Shooting Life by George Bird Evans. Bill was quick to point out that Mr. Evans was somewhat of an enigma for the WVDNR. He was a gifted writer and enthusiast for upland game bird hunting. Evans was a strong critic of late grouse seasons. He maintained that late season hunting suppressed grouse populations.

Due to his notoriety, Mr. Evans had a lot of influence in his home state of West Virginia. His writings were repeated throughout the region by outdoor writers and avid grouse hunters whenever grouse populations fluctuated. It turned out that his book and theory of hunting effects on grouse shaped my career.

Initial Investigations of Virginia Ruffed Grouse

Following a sharp decline in grouse flushing rates in 1976, the Virginia Game Commission shortened the grouse season by two weeks. Mr. Joe Coggin, then-Supervisor of Game Research, told me George Bird attended the regulation hearings and spoke in favor of a shorter grouse season. But Joe was not sure late season hunting was limiting Virginia grouse. He asked researchers at Virginia Tech to begin an investigation.

I was fortunate to be the first Virginia Tech graduate student in this investigation. My advisor, Dr. Roy Kirkpatrick, directed me to begin studying the nutritional ecology of grouse in Virginia. I specifically examined food quality and grouse condition. I found grouse were able to build body fats on diets of soft mast in the summer and fall, and acorns in the fall and winter. We hypothesized that winter survival and reproduction could be impacted without high-quality foods.

Years later, I became Virginia’s Ruffed Grouse Project Leader. The question of the impacts of late season grouse hunting persisted in the upland bird hunting community. The fundamental question was whether late season hunting was additive or compensatory mortality.

Is Late Season Ruffed Grouse Hunting Additive Or Compensatory?

The basis for sport hunting is that hunting losses are compensated by fewer natural mortalities. Thus, post-hunting populations compare to unhunted populations. Wildlife managers also considered a third hypothesis—that hunting was compensatory up to some threshold where it then becomes additive. The obvious concern was that hunting would cause a decline in breeding populations and result in long-term population declines.

Regrettably, wildlife studies have concluded different results on hunting effects on ruffed grouse populations. One explanation is that ruffed grouse ecology and hunter pressure vary widely across its range. After all, it is the most widely distributed resident game bird in North America. Key factors wildlife managers ideally want to know before drawing any conclusions about hunting impacts include survival rates, hunting mortality rates, and reproductive rates. Knowledge of the impacts of weather, predation, diseases, and habitats on all these parameters are important considerations for managers. Thus, it is understandable that different conclusions have been reported about hunting and other factors limiting grouse populations across their range.

Nevertheless, decisions must be made about setting seasons, with or without expert knowledge. Criticism and complaints from concerned users come when populations and harvests are less than satisfactory. Joe Coggin had felt the heat. Now it was my turn as concerned grouse hunters continued to raise the question about hunting impacts.

Concerned hunters wanted to know if those hens harvested in late season would live and reproduce, thereby increasing the population.

The Appalachian Cooperative Grouse Research Project

Together with Jeff Sole, Upland Game Bird Project Leader in Kentucky, we conceived a research project to address these concerns. It took several years of planning and coordination, but we eventually realized our wishful thinking of a cooperative multi-state research project to investigate hunting and other factors limiting grouse populations.

The project started small, but interest in grouse was high in the region. Eventually, seven state wildlife agencies joined the project. The project was titled the Appalachian Cooperative Grouse Research Project (ACGRP). Six years later, we had caught and radio collared 3,118 ruffed grouse at 12 study sites in eight states. A total of 17 graduate students at eight universities worked on the project.

As part of our primary objective, we closed the hunting seasons at three study sites over the project’s final three years. We compared survival rates in the closed areas to four control sites where hunting continued into February.

We found no difference in survival rates between hunted and un-hunted populations. In effect, we observed that hens “saved” from hunting were nevertheless subject to high predation rates in March, April, and May. The primary spring predators were hawks and owls. It is important to note that hunting mortality rates in our studies averaged 12 percent.

Pat Devers, Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech working on the project, wrote, “It is important to recognize that we cannot assume harvest rates higher than those observed in this study are compensatory; nor can we extrapolate our results beyond the Appalachian region.”

We did find hunting increased grouse winter home ranges.

What Is Limiting Grouse Populations In The Appalachians?

Surprisingly, we found survival rates in the region were comparable to or even higher than studies from the Lake States and New England. Most of the mortalities were predation, with the greatest losses from avian predators, primarily in the fall and spring. We found Cooper’s hawks and owls were the primary predators.

Reproductive Rates

In contrast, we found reproductive rates in the region were lower. Most notably, chick survival rates and renesting rates were lower in the region’s most abundant forest type, oak-hickory. We found significant annual variation in reproduction in oak-hickory forests that correlated to acorn crops. We noticed hens in these forests tended to forgo nesting in the spring following a poor acorn crop.

Body Condition

Bob Long, then-M.S. student at West Virginia University (WVU), found that nutrition and pre-breeding condition had a significant impact on reproduction. Bob suggested that hens have a threshold of approximately 11 percent body fat to be successful nesting.

Weather And Predation

Beyond body condition, weather and predation were responsible for regulating chick survival rates. Using miniature transmitters on grouse chicks, Brian Smith, then-Ph.D. candidate at WVU, found predation and weather were equally responsible for chick losses.

Additional Findings From The ACGRP*

In contrast to oak-hickory habitats, grouse in hardwood forests (cherry-maple) in the Appalachians have more reliable food resources and more predictable reproduction. John Tirpak, then-M.S. student at California University of Pennsylvania, found nests in dense understories were more likely to be successful than those in sapling stands and those near openings.

Darroch Whitaker, then-Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech, studied the home ranges and space use of grouse across 10 study sites. He examined 67,814 locations of radio-marked grouse to determine home ranges of more than 1,000 birds. Darroch found that females had larger home ranges than males, juveniles had larger home ranges than adults, and hens with broods used moist bottomlands and riparian areas. He concluded managers should maintain and enhance these critical areas to increase grouse reproduction and grow populations.

We offered extensive suggestions to land managers on the best habitat management practices to improve ruffed grouse habitats (Craig Harper and Ben Jones, UT and Darroch Whitaker, VT). We recommended shelterwood cuts to landowners and managers. (A good number of trees, preferably oaks, are left in shelterwood cuts.) These residual trees offer a more appealing appearance than traditional clear-cuts. Additionally, residual oaks provide acorns, a vital resource that supports grouse condition and reproduction. The developing understories provide essential protection from avian predators. The research team also evaluated other forest harvest systems, prescribed fire, and forest roads and openings.

All totaled, 17 theses and dissertations resulted from the project. We also produced a book summarizing our most important findings: Ecology and Management of Appalachian Ruffed Grouse. Our hope with the book was to condense important ACGRP findings and make them accessible for wildlife managers, hunters, and grouse enthusiasts alike.

Appalachian Ruffed Grouse Post-ACGRP

The ACGRP concluded in 2002. Is the volume of ACGRP information now dated? What has happened to grouse populations in the region since 2002? As avid Appalachian ruffed grouse hunters will tell you, the news is not good. Flushing rates have sharply dropped. Wildlife agencies suggest grouse numbers in the Appalachians have declined 30-70 percent since 2002. Declines since 2017 are particularly troubling. However, grouse populations and hunting are stable in other regions of the country, namely in Maine and the upper portion of the Great Lakes region.

State wildlife agencies have been extremely concerned with these downward developments. Managers have been planning and revising conservation strategies to address the declines. They recently announced a coordinated regional initiative to address regional decline in ruffed grouse populations: “Eastern Ruffed Grouse Conservation Plan – 2025-34.” The plan does a great job of explaining where ruffed grouse are now and how we can change the trajectory of their decline.

Drivers of Grouse Decline

The plan identifies the loss of young forests, changes in climate, predators, land use, and West Nile Virus for the declines in grouse populations. However, landscape-scale loss of young hardwood forests is the primary driver in the decline in ruffed grouse populations in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Southeastern states. Grouse populations are stable or increasing in aspen forests with short timber rotations and an abundance of young forests.

The daunting challenge for grouse managers will be to somehow slow or reverse the landscape-scale loss of young forests. One of the most significant challenges is the decline in demand for oak products in flooring and cabinets. That decline has resulted in a drop in both demand and price of the most abundant trees in the region. This has led to the closure of mills and reduction in logging businesses.

There are large acreages of National Forests in the Appalachians that offer great potential for young forests. This acreage is obviously important to grouse hunters as it is frequently our primary destination. Indeed, the VA Department of Wildlife Resources offers an app that maps the location of young forests in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests for grouse hunters. However, the creation of young forests in National Forests is a challenge. The appeals and lawsuits from individuals and groups that oppose timber harvesting would be a barrier to management. The opposition has effectively accelerated the decline of wildlife that require young trees in National Forests.

There are some good examples of state wildlife and forestry agencies doing good work to create young forests. Unfortunately, most states do not have enough land or the resources to provide significant opportunities for grouse management. Pennsylvania is the exception as it has over 1.5 million Game Lands it actively manages. There are some encouraging examples of timber companies that still own large tracts that are actively managing in the region.

Hunting Declining Grouse Populations

The ACGRP and other research have found that low harvest rates did not impact grouse populations. The latest research, in Maine from 2014-16, also concluded late season hunting was not excessive and was consistent with sustainable harvests. Nevertheless, biologists setting grouse seasons will be expected to consider hunting impacts on sharply declining ruffed grouse populations. Pressure will be brought to bear to “do something” even though a reduction or closure may not change the trajectory of grouse populations.

I first heard the term “Laws of Diminishing Returns” applied to game harvest theory by the late Mr. Jack Raybourne, former Chief of the Wildlife Division in Virginia. He commented that season length is irrelevant as hunters adjust their efforts based on the population levels. Applying Jack’s theory, grouse harvest rates have declined sharply as the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources recently reported grouse hunter numbers, effort, and harvests have declined more than 90 percent between 2001 and 2023.

Overlapping Deer Seasons And Grouse Seasons

Several Eastern states (NY, WV, VA, KY, GA) still hunt grouse in February. The length and timing of deer seasons that coincides with grouse hunting is a consideration as most grouse hunters choose not to hunt during deer seasons.

Regardless, some states (e.g. VA) have relatively long deer seasons that effectively reduce grouse hunting mortality rates. Others have shorter seasons, generally ending at the beginning or end of December. Some states (IN, NJ, RI) on the fringe of grouse range have closed grouse seasons.

Indirect Impacts Of Hunting

There is some concern for the indirect impacts of hunting on grouse. We did see an increase in grouse home ranges in ACGRP during hunting seasons. Repeated and frequent flushing could impact an individual’s fitness and survival. We saw grouse return to their smaller, we assumed, preferred home ranges when the season closed. However, winter survival rates in ACGRP were high.

Pennsylvania’s Responsive Grouse Harvest Framework

Concern for declining flushing rates led the Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) in 2018-19 to implement a Responsive Grouse Harvest Framework. It adjusts late season hunting based on annual estimates of grouse population levels from hunter flushing rates, reproduction based on summer brood sightings, and an index of West Nile Virus. Depending on their population assessment, their late season (post-Christmas) can either be canceled or offered for one or four weeks.

West Nile Virus

West Nile Virus (WNV) is another major consideration when discussing the current and future status of ruffed grouse. The virus, which can be deadly to ruffed and sage grouse, was first confirmed in the United States in 1999. Its impact on a host of other wildlife, horses, and humans is well documented. It is interesting to compare population trends of ruffed grouse to Cooper’s hawks, perhaps its greatest avian predator. Both species are susceptible to WNV. However, Cooper’s hawk populations have increased 3.2 percent annually since WNV according to Christmas Bird Counts.

Summer weather has a big impact on mosquito populations and the spread of WNV. A regional study of WNV prevalence in Appalachian grouse was coordinated by Southeast Wildlife Disease in 2018-20. In the first two years, we found eight to 12 percent of grouse in Virginia had WNV antibodies. These preliminary results suggested some ruffed grouse are resistant to the disease and may offer some level of population immunity to WNV. Results of the study are expected soon.

Additionally, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation recently initiated a study to investigate WNV impacts on ruffed grouse abundance and condition. Other research suggests WNV effects on ruffed grouse may be reduced at higher elevations. Thus, there has been a focus on creating young forests at higher elevations.

Some biologists have expressed concerns about genetics of isolated grouse populations. The PGC is leading a regional study to investigate this theory and the importance of connectivity of grouse populations.

The Future Of Appalachian Ruffed Grouse

What does the future hold for Appalachian grouse hunters? Many have told me they are giving up and not replacing aging bird dogs. The die-hards search for remaining good habitat. Many are spending more time hunting American woodcock. Marc Puckett, VA Quail Project Leader, tells me he is encouraged by bobwhite quail adaptations to pine forest management in eastern Virginia. He has seen encouraging numbers of quail and quail hunters on public lands. Personally, I have been amazed to see the numbers of upland hunters chasing prairie grouse. My dog now knows a bird hunt may involve a good road trip.

My thanks to Bill Igo, George Bird Evans, Jeff Sole, and the ACGRP team for our contributions to ruffed grouse knowledge. I encourage all to invest in our book. It is a good read for grouse die-hards. By the way, I get nothing from this endorsement other than the satisfaction of knowing that if you are reading this, you might find something useful buried in our work.

*Due to an editorial error, this story was originally published without the text below. This article has been updated on 3/24/25 to include the rest of Gary’s article.

Gary recently retired as Forest Game Project Leader with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. He worked on ruffed grouse, wild turkey, and American woodcock research and management projects. Gary has owned a wide variety bird dogs including Brittanies, English Setters, GSPs, and now, English Pointers.

Gary Norman is a highly respected biologist. I had the opportunity to meet and talk with him years ago at Canaan Valley at a Conference on the Appalachian Grouse study. Other notables were michigan DNR AL Stewart and Bill Goudy.

Now there are other factors including the effects of altitude on grouse survival and of course West Nile virus.

Congrats Gary on your retirement. Hope you and the dogs are still hunting those Upland Covers.

.

Great research and very well written article from a true expert on the subject. The article was short, sweet and to the point. Like any good research it brings up many more questions than it can often answer. Well done!

Would love to see an article build on the broader issue of early successional forest habitat with accompanying regional/historical mapping trends. As modern even-aged forest management practices decline in application, we find ourselves with less habitat for ruffed grouse and other species to populate and prosper. I appreciate that this informative and thought-provoking article touches this issue of forest management in its closing summary.

I have watched the ruffed grouse population plummet in SE TN over the past 45 years as critical habitat was eliminated with timber harvests being reduced and basically eliminated. It is possible that they are attempting a comeback presently. One can only hope.

Among the factors affecting ruffed grouse populations an important and overlooked one is the rise in coon, skunk and possum populations since they are no longer hunted or trapped the way they were 50 years ago. These everpresent predators affect all ground nesting birds, along with the high coyote population in many areas of the eastern hardwood forests. Does anyone know of studies that have been done on grouse populations in areas where those predators have been controlled or eliminated vs an area where they are abundant ? And yes, west nile virus is a head shaker when it comes to adding anothet mortality factor to the grouse populations and their reproductive success.

I was lucky enough to have experienced awesome grouse hunting in northwest PA in the 70’s. By around 1982 or so the woodcock (which were abundant] in the 70’s were also disappearing fast just like the grouse disappeared. One thing I do know is that the thick logged over areas where the woodcock and grouse thrived, became big woods. The creek bottoms and swamps became to big with zero brushpiles and thickets. Going back to our family camp, in which our property ran into State game lands, was now big woods with no thick logged over areas. The PA game commission tried little clear cuts. The clear cuts aren’t big enough to help. The state game lands there at camp is 5000 acres. There are many game lands in that area of PA. The clear cuts need to be a lot bigger than 100 acres. At least 3000 acres should always be clear cuts of different ages to make any difference. Food was abundant like the green leafy ground [I don’t remember the name ] anymore was growing everywhere. All harvested grouse had the green food in them. Wild grapes were everywhere, raspberries blackberries and wild strawberries were everywhere. After the woods got too big, all that food went with it. I’m talking 30+ flushes in just two hours of hunting to nothing in a 4 year time frame. We have our property logged as much as possible to try and help. The game commission control enough property in that part of PA to do a better job. They need bigger areas logged to remotely make a difference. The natural foods are still there but disappear as the woods get to big. Now for the predator problem. After serving this great country for a few re-enlistments, me and my wife stayed in a pheasant and quail state. The bird hunting on the public lands was awesome. Pheasant and quail everywhere. That has left the scene too. To much farming on the public lands has taken away too much habitat. They started burning to often and too much average. The best winter survival habitat, which is awesome nesting and brooding habitat is burned about every three years. Pushing the birds into substandard areas for winter survival and nesting does not help at all. Wildlife and parks is their own worst enemy. The farmed fields have rows of crops like milo, corn, and beans the must be left by the farmers that use the land. The rows that are more than 20 yards from the cover are nothing more than death traps. In snow one not long ago, I followed a bird track that tried to go out to those rows of corn away from the cover. When I reached that row probably 50 yards, I found ringneck feathers in a poof in the snow. Zero predator tracks in the snow. Had to be a hawk. I followed that row of corn maybe 200 yards back to my pickup. In that two hundred yards, I found more poof in the snow. In total, 1 ringneck, two hen pheasants, 3 quail, a couple of morning doves and a few normal bird pools. The hawks a doing big numbers on the bird population. If wild and parks would make the standing food all run along the bird cover say 10 rows of corn, milo and others and not out in the hawk zone, numbers of birds would survive to nest again. Forcing birds out of cover to feed is dumb. Plain dumb. Just trying to reference what is going on. Unfortunately, it’s our wildlife biologists doing most of the harm. I watched PA and this state go to hell and the biggest problem is the biologists themselves doing the damage. Not paying attention to what is going on. It can be fixed in both states if we pay attention to details. Bigger clear cuts in PA and stop the habitat destruction out here. It’s all self inflicted wounds. Predators from snakes up to hawks all like eggs all the way up to grown pheasant are loved by the predators. A little of common sense would go a big way in helping. Burn as needed policy, not every third year? all grain fields need standing for for the 10 rows or so from habitat, not out in the middle where hawks a the ultimate bird killers. And a few more things. PA just need to do bigger acreage clear cuts and so on. Hunting doesn’t hurt the bird problem, habitat destruction is the problem I have seen drought out here have little impact as long as the habitat is there. No habitat, no animals. It’s that plain and simple. That’s all that is needed. Good habitat, good hunting. Plain and simple. Fix it please. It’s not hard. A good pheasant hunter can look at a place and say there will be birds or there won’t be birds there. Good pheasant is good everything habitat. I’ve seen it . Habitat first, natural food comes with it. PA, you need to push more logging in bigger areas. It will help greatly. My opinions based on experience. Good luck!>⁸