Home » Grouse Species » Ruffed Grouse Hunting » Trial by Fire: The Loss and Potential Recovery of Ruffed Grouse Habitat in Virginia

Trial by Fire: The Loss and Potential Recovery of Ruffed Grouse Habitat in Virginia

Born and raised in Virginia, Ryan Dawson is a physical…

When it comes to restoring ruffed grouse habitat, particularly in Viriginia, our conservation practices need a trial by fire.

This article originally appeared in the winter 2024 issue of Project Upland Magazine.

As a young boy, I spent more time outdoors than anywhere else. I dedicated my time to whitetails in the fall, eastern turkeys in the spring, and whatever fish I could find in the summer. I hunted rabbits, squirrels, doves, and ducks. Simply put, if there was a season for it, you could find me chasing it—except for upland game birds.

Upland birds were exempt from my long list of hunting experiences, not for lack of desire but quite the opposite. My father and grandfather filled my mind with story after story of the sport. He provided me with all but the lived experience.

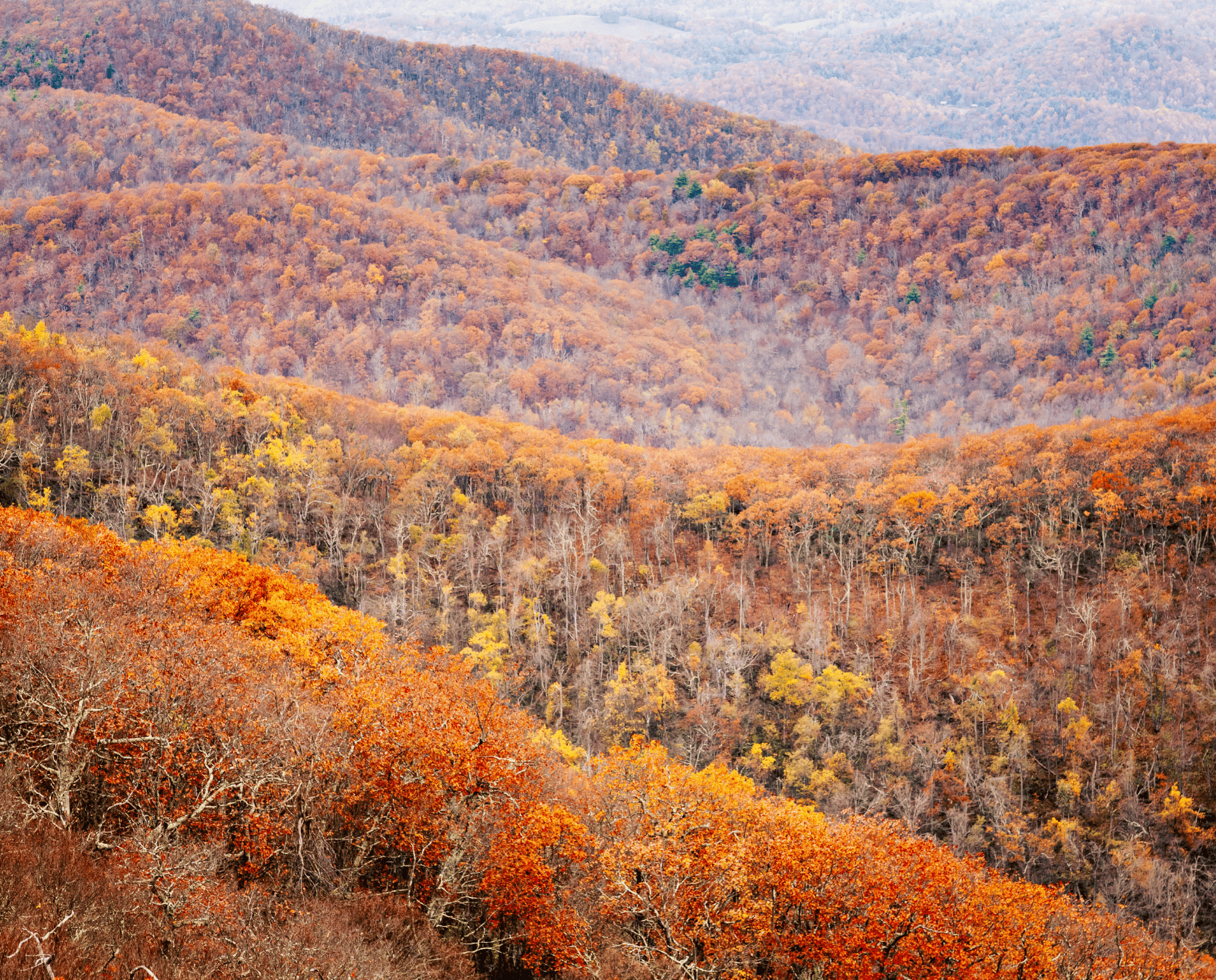

They often described the crescendo of a grouse’s drumming echoing through the ian hardwoods and the beauty of a strutting cock dancing around a Forest Service roadbed. My grandfather recounted hours spent training English Pointers and Setters. My father shared stories of grueling hikes through thick laurel hells. Although he complained about the breakneck pace maintained by my grandfather and his friends, he always concluded with how the adrenaline rush from a flushing ruffed grouse made it worthwhile.

Word by word, story by story, a passion for upland hunting grew in me, although I never spent a minute in the field. Frankly, they couldn’t have done a better job of making me want to experience the world of upland bird hunting.

However, the days of my childhood and early adulthood spent in the grouse woods were a far cry from the stories of the late sixties that my grandfather shared—stories of action-filled days, flushing twenty-three birds and bringing twelve to hand. My efforts pursuing Virginia grouse were met with very little reward.

I raised and endured the heartbreak of losing my first gun dog. My boots walked hundreds of miles through denser hellholes than I knew existed. I trekked deeper into the National Forest than most are willing to go at all in pursuit of a bird the size of a Cornish game hen. All that effort, and we only ever flushed two ruffed grouse and brought no birds to hand.

As the miles and cover wore on me, my search for these mythical birds slowly transitioned from the hills of Appalachia to the computer. I scoured the Internet. It didn’t take long to understand why I had been so unsuccessful in finding birds in Virginia. The results of a quick search titled “Appalachian Ruffed Grouse Populations” painted an overwhelmingly dismal picture of the story of ruffed grouse conservation in the Southeast.

The Dismal Picture

My search eventually led me to a 2020 episode of the Dear Hunter Podcast. In it, Dr. Ben Jones, CEO and President of the Ruffed Grouse Society, discussed the future of ruffed grouse in the eastern and midwestern United States. He stated, “The projected path right now is zero. It’s local extinction.” Dr. Jones later mentioned Indiana’s ruffed grouse management catastrophe. He said, “In less than the time that I’ve been around as a 45-year-old, the species has nearly disappeared with a 90 percent reduction…the true thing about this is all the southern Appalachian states are on the exact same trajectory.”

“The general decline in Virginia’s ruffed grouse population has been ongoing for several decades and dates back to the 1960s and ’70s,” said Michael Dye. He’s an upland bird biologist and the statewide turkey and grouse program coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. I reviewed surveys and research from various sources, including state wildlife agencies. The data reiterated Dye’s words, demonstrating a decline in Appalachian ruffed grouse over the past 50 years.

One of the most commonly used tools by state wildlife agencies are grouse hunter surveys. They help estimate grouse populations. The resultant statistic is the flush rate, or the number of flushes per hour of hunting. In Virginia, these surveys have demonstrated a 68 percent decline in flush rate since 2002. There’s been a 9.7 percent annual decline in flush rate since 2009. According to Dye, harvest estimates in Virginia also indicate a decline in ruffed grouse populations. There is an “84 percent decrease in our grouse harvest coupled with a decrease of 74 percent in grouse hunters.” Unfortunately, many of these populations reach new all-time lows every year.

Coincidentally—or perhaps not—the early to mid-1900s marked a pivotal point in United States forestry management practices. Commercial logging became a significant industry by the 1800s. Clear-cutting enormous swathes of land was common practice by the mid-1800s. Only poor-quality dead timber, too small to be utilized as lumber, remained.

While the lumber industry is selective, nature is not. This dead timber served as an accelerant for wildfires, which were often anthropogenic in nature. These fires became so fierce and frequent that they offered minimal opportunities for reforestation. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) intervened. By the mid-1900s, fire prevention and suppression practices occurred on a large scale. This marked the beginning of a period recognized as the fire exclusion era.

Initially, these practices served their purpose by providing parcels of clear-cut land the reprieve necessary to regenerate forests. However, the impact of these practices quickly extended beyond that. Fire, in all its capacities, became demonized as a result of the USDA and private interest groups pouring resources into advertisements and campaigns, including Smokey Bear. These efforts resulted in the near extinction of wildfires and extensive suppression of prescribed burns in the Southeast.

Fire And Grouse

Historically, fire has been a vital component of both natural and anthropogenic forest management. In the absence of humans, wildfires are one of the few sources of forest revitalization. The redirection, control, and suppression of wildfires by Native American tribes are often recognized as the origin of prescribed burning. They date back long before the arrival of Europeans on the North American continent. Fires occurred in the Appalachian region at relatively frequent intervals throughout indigenous habitation and European settlement.

According to the USDA’s Fire History of the Appalachian Region: A Review and Synthesis, the frequency of these burns served many functions. Frequent burns prevented the accumulation of excessive fuel, limited the temperature and intensity of wildfires, and reduced overall damage. This increased frequency also maintained hard mast-producing timber stands. They limited the ability of fire-susceptible species, such as sugar maple, to dominate understories. Without frequent burning, sugar maples grow quickly. They easily outcompete slow-growing white oaks, whose acorns compose a large portion of the Appalachian ruffed grouse diet.

Moreover, frequent burning allowed for a biodiverse understory by opening dense canopies created by woody growth such as rhododendron and mountain laurel. Higher volumes of herbaceous plants also supplement ruffed grouse diets. However, when considering ruffed grouse habitat, the most important effect of higher-frequency burning is arguably the resultant increase in early successional growth.

The early successional growth created by fires is vital for ruffed grouse brooding. North Carolina is a great example of this. In “Managing Habitats for Ruffed Grouse in the Central and Southern Appalachians,” multiple biologists, including Dr. Ben Jones, described the results of a 700-acre prescribed burn. They stated, “The treated area supported a diverse herbaceous community, which was used almost exclusively by several grouse broods.”

The importance and effectiveness of fire’s role in Appalachian ruffed grouse habitat management becomes evident when comparing the timeline of fire suppression with Appalachian ruffed grouse populations. By the mid-1900s, fires had all but ceased to exist in the region. Shortly thereafter, grouse populations began trending downward. Without fire, there are minimal natural opportunities for early successional growth and improved biodiversity. Although necessary at the time, the implementation of fire prevention and suppression practices marked the beginning of the cessation of a millennia-old regenerative process—a process that played a key role in ruffed grouse survival.

In the words of Michael Dye, “Forest management is a key component to resolving the decline .” However, the demonization of fire initiated a cascade of privately funded anti-active forestry management agendas. Although this effect was unintentional, it continues to limit the implementation of active forestry management practices in the Southeast today. Rather than continuing to spend time and resources to further document the already evident decline in ruffed grouse populations and habitat, these organizations should be utilizing those resources to begin correcting the problem.

While the answer to all wildlife conservation issues is multifaceted, the phrase “the simplest solution is usually the correct one” seems to fit this situation all too well. With fire went Appalachian biodiversity and early successional habitat, and with their loss went the southern Appalachian ruffed grouse.

The answer to restoring southern ruffed grouse populations—or, at minimum, a piece of the puzzle—is fire.

Hope For The Future

In an ideal world, these burns would be prescribed on a case-by-case basis. Each burn would uniquely supplement the existing forest. Dry areas would be burned frequently, every two to three years, at high intensity. This strategy diminishes woody cover and increases the volume of herbaceous cover. Areas with more moisture would be burned less frequently and at lower intensities. This removes leaf litter and promotes increased plant diversity. Stands of mature timber would be selectively harvested prior to burning, using methods similar to those in mesic areas. This approach would open the canopy enough to promote increased growth at the forest floor, maintain mature hard mast-producing trees, and remove litter.

Jim Cook is a retired man with an impressive resume in forestry services ranging from smoke jumper in the Pacific Northwest to leadership positions within the Virginia Department of Forestry. He explained that prescribed burning works “extremely well” for restoring and managing ruffed grouse habitat in the Southeast. He has even successfully harvested grouse in areas he previously burned.

Active forestry management remains an underutilized practice in the southern Appalachians. Private landowners with assistance from wildlife and conservation agencies perform the majority of active forest management. Cook was responsible for using prescribed burns to manage approximately 1,000 acres annually during his time with the Virginia Department of Forestry. He acknowledged that, although better than the complete absence of burning, one thousand acres is far from enough. In fact, it constitutes just 0.06 percent of the land in Virginia that falls within national forests, nearly all of which could be suitable ruffed grouse habitat.

There is no record of significant change in these numbers since Cook’s retirement about 15 years ago. However, many conservation organizations are busy laying the groundwork for what could result in a massive uptick in active forestry management on Virginia’s public lands.

The Ruffed Grouse Society is an organization founded in the very same hills where I played as a boy. It is establishing partnerships between forest agencies and forest product industries across the Southeast under its Stewardship Project. This work aims to facilitate improved implementation of forest management practices on both private and public land. The chances of this story becoming a success increase as passionate, conservation-minded individuals fill positions in state wildlife and forest management agencies.

The wheel of ruffed grouse habitat management turns slowly. Blame for the downfall of these beautiful birds cannot be placed entirely on one party. However, without action, it is clear that the current trends will continue to creep towards eradication.

Over the years, my grandfather and father, along with many other hunters, stopped grouse hunting due to the decreasing population. As I grew older, the stories my grandfather told shifted from awe-inspiring to dreary and bleak. The story he tells most often now is of one of the last Appalachian ruffed grouse hunts of his life, which took place in the early 2000s. He, a group of other men, and half a dozen of their dogs hunted a 1,000-acre plot of private land. Although they hunted it for several days, they had no points or flushes.

Last fall, I had my first chance to chase these birds in a setting that offered the potential for success. Unsurprisingly, this opportunity came with the same two men who inspired me to pursue the sport in the first place.

My grandfather, father, and I marched into one of the many island mountain ranges in Montana in search of bringing stories of healthy ruffed grouse populations into our reality. With the effects of age limiting both my grandfather and father, the mountains proved to be difficult terrain. I hiked up hillsides, working my Vizsla puppy through thickets of dense hawthorn while they paralleled the creek.

Much to my surprise, the dog screeched to a staunch point. I yelled down to ensure everyone knew of the point. I eased forward, softly woahing and patting my pup on the head as I passed by him. Without warning, three ruffed grouse thunderously erupted from under the bush in front of me. They glided down the hill toward my grandfather. Shots rang from his double-barreled 20-gauge, and two of the birds crumpled as the loads met their flight path. A solid retrieve and return to hand turned the page on a lifelong dream of mine.

As I pulled my sweat-stained socks off my blistered feet on the tailgate, with our three ruffed grouse and my pup beside me, I realized that none of the other birds we harvested on this trip meant an ounce as much as these. Not because of the meat or the dog work, but for the memory, the camaraderie, and the hope it instilled for ruffed grouse populations in the southern Appalachians.

One day, God willing, I’ll find myself in the hills chasing these magnificent birds with my son and grandson. I hope that it’s in my home state of Virginia, on the same hills that I once shared with my father and grandfather. I hope that I can remember the fruitless hours and miles of my youth as a fond memory—a low point in the hopeful underdog story of the Appalachian ruffed grouse. But I know, as I presume many others do, that in order for that to happen, we’ll have to give our conservation practices nothing short of a trial by fire.

Born and raised in Virginia, Ryan Dawson is a physical therapist by trade. Outside the clinic, he can be found pursuing anything that has earned the title wild game, from trout and upland birds to rabbits and elk. Ryan can be found somewhere in the plains or mountains of Montana with his wife, Meredith, and Vizsla, Major.