Home » Woodcock Hunting » The Evolution of American Woodcock

The Evolution of American Woodcock

Sage Marshall is a longtime outdoor journalist from southwest Colorado.…

The leading theories surrounding woodcock evolution in North America

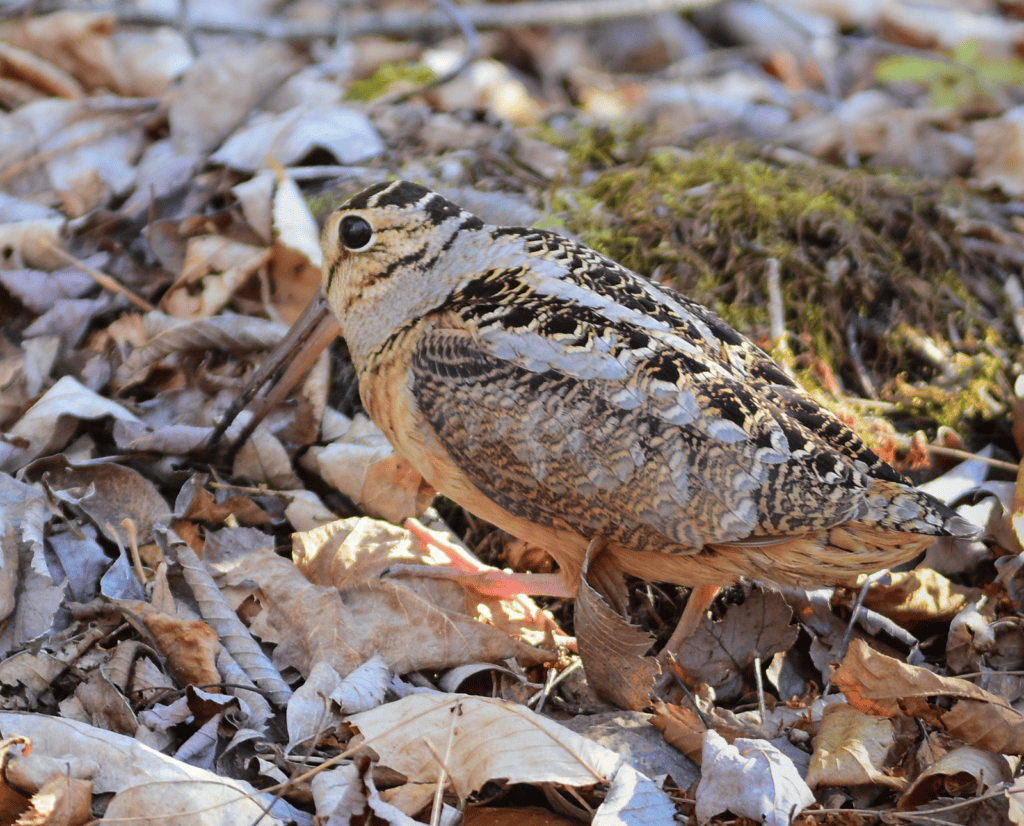

The American woodcock, also known as the timberdoodle, is one of the most well-known—and distinctive—game birds in North America. To put it simply: there’s no other upland bird quite like a woodcock. The species is unique for being one of the only migratory birds upland hunters chase. The birds also have unusual body compositions with small, rounded bodies, long pointed beaks, and eyes set far back in their skulls. They also walk with a strange “bobbing” gait that distinguishes them from other birds—traits that reflect the evolution of woodcock into highly specialized forest dwellers.

How did these oddballs of the forest come to be? Here are the leading theories surrounding woodcock evolution.

Woodcock Migration Patterns

The American woodcock is technically a shorebird. However, the species lives in forested areas where it primarily forages on earthworms. Woodcocks are part of the Scolopacidae family and are in the genus Scolopax. The most closely related species in the genus is the Wilson’s snipe. Snipes are another migratory gamebird popular among wingshooters, though snipe live in wetland areas.

One of the defining characteristics of woodcock—and one of the reasons hunting them can be so hit or miss—is its migration patterns. The woodcock evolved to migrate south during the cold weather months to be able to forage on unfrozen soil. They return north during the summer to breed and feed. Some southern populations do not migrate.

Erik Blomberg, Associate Professor and Chair of Department of Wildlife Fisheries and Conservation Biology at University of Maine, is part of the Eastern Woodcock Migration Research Cooperative (EWMRC). The EWMRC a collaborative group of researchers that study woodcock migration with satellite tracking technology.

Studying Woodcock Migration

In an article published in the Ruffed Grouse Society and American Woodcock Society, Blomberg writes many questions remain about woodcock migration. Researchers say it is “highly variable,” depending on location and subpopulations. That said, scientists have been able to pinpoint what a typical woodcock fall migration looks like.

“The ‘average’ woodcock in the Eastern Management Region begins fall migration around November 7 and takes about four weeks to travel just under 1,000 miles to its wintering destination, stopping five or six times along the way,” writes Blomberg. “Most of the stopovers last a single day while around one in five stopovers is prolonged and lasts 10 days on average.”

Itinerant Breeding

One truly unique evolutionary characteristic of the timberdoodle’s spring migration is that it practices “itinerant breeding,” a rare biological quirk that means birds breed and nest multiple times in different places in one season. This finding was revealed in a 2024 study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences by University of Rhode Island researchers.

“This paper provides the best documented case of a migratory bird that is an itinerant breeder. Such itinerant breeding is exceptionally rare,” said Scott McWilliams, URI professor in natural resources science.

“We often think of spring migration, breeding, fall migration, and wintering as separate events,” URI Ph.D. student Colby Slezak told Science Daily. “But woodcock are combining two of these into one period, which is interesting because both are so energetically expensive.”

According to Blomberg, the woodcock’s return migration is typically slower than its fall migration. As it travels north, the species waits for snow to melt along the way. These birds also face unfavorable winds. While itinerant breeding is costly, it may allow woodcock to be flexible to environmental changes and predators.

Woodcock Evolved Quirky Physiological Traits

Woodcocks are funny-looking birds. The species’ appearance, however, is the result of evolutionary adaptations that allow it to survive in its preferred forested habitats. For instance, its earth-tone feathers blend into the forest floor, making them difficult for predators to spot.

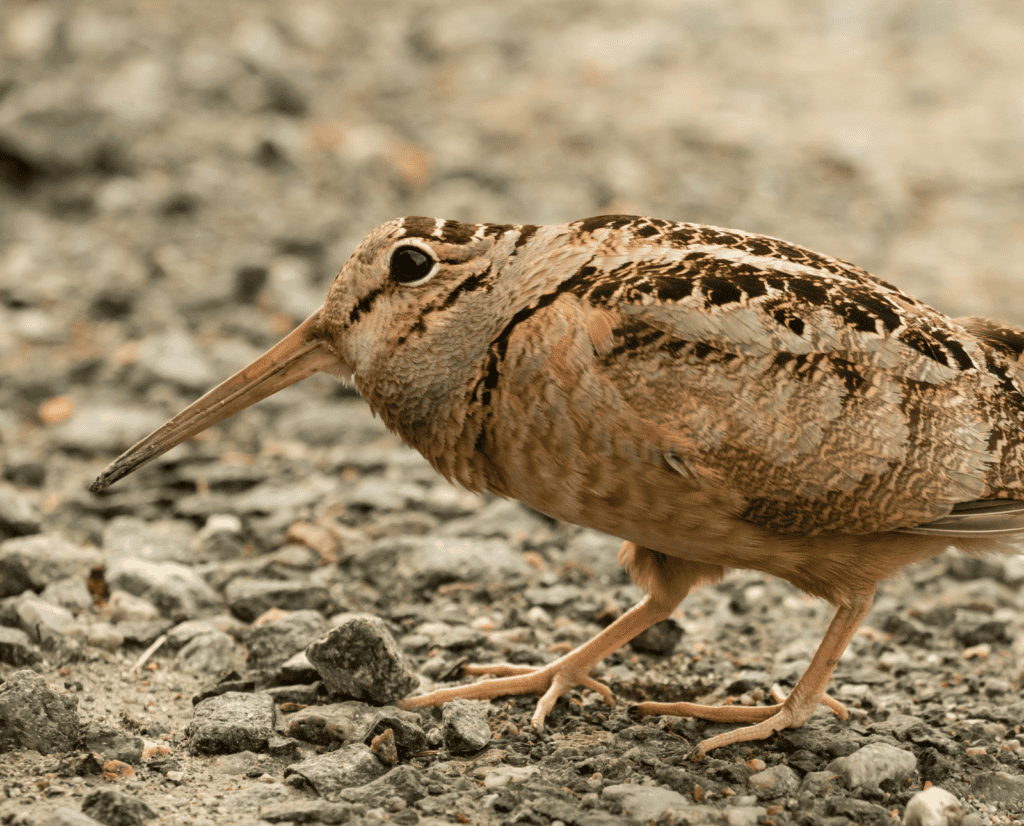

According to the National Park Service (NPS), the woodcock’s specialized bill has a “prehensile tip.” This means its capable of grasping or holding. Because 75 percent of the bird’s diet is comprised of earthworms, the woodcock evolved to be able to open its beak even when it’s plunged into the soil.

Another unique adaptation is the location of the woodcock’s eyes. Their eyes are set further back and higher up in their skulls than other birds. Scientists theorize that this eye location gives the birds a 360-degree field of vision, allowing them to forage in a forest’s floor while simultaneously keeping an eye out for danger. To make this adaptation, the entire composition of the woodcock’s brain changed.

“The bird has an ‘upside down brain’ compared to other birds,” explains the NPS. “The cerebellum, controlling muscle coordination and balance, is set below the rest of the brain and above the spinal column.”

Why Do Woodcock Bob?

By far one of the most unique and least understood aspects of the woodcock’s evolution is the way the species moves. Woodcocks are known for “bobbing” or “dancing” while they walk. The back-and-forth striding behavior is seen even among young chicks. It has also made for some incredibly popular YouTube videos such as this one.

But why did woodcocks evolve to do this funky behavior? Scientists have come up with some theories, though none of them are definitive. In a 1982 study, ornithologist William H. Marshall observed woodcock behavior in the field for extended periods of time. Marshall detailed four prevailing theories for the unusual motion at the time: 1) a nervous tick resulting from fear 2) mimicking the motion of leaves 3) mimicking shadows and 4) attempting to detect earthworms by exerting extra pressure on the forest floor.

In 2016, Dr. Berndt Heinrich put forward an alternative in a scientific study published in the journal Northeastern Naturalist. Heinrich observed that timberdoodles only exhibited the rocking behavior when they knew they were being observed and were in open habitat—where they were more likely to be spotted by predators. Thus, Heinrich theorized that the behavior was akin to “stotting” in springbok.

“In certain situations, some animals make themselves highly conspicuous to predators, as a defense.” argued Heinrich. “I suggest that the Woodcock rocking-walk display is a response to what it perceives as a mild potential threat situation that is not severe enough to initiate predator-avoidance tactics to disrupt it into flight or cryptic hiding. The Woodcock’s rocking-walk display may act as a signal in a situation of a perceived potential audience or a predator, indicating that it is aware and can explode off the ground and escape if the predator seems likely to attack.”

The Final Word on Woodcock Evolution

Woodcocks are clearly one of the most atypical upland birds around. But their distinct physiology, flexible migration strategies, and curious rocking behavior are all the result of evolutionary adaptations that have made them remarkably suited to life in forests. These traits—especially their ability to forage in diverse environments, evade predators, and even shift breeding locations on the fly—highlight the woodcock’s capacity to respond to environmental change. While the species has experienced some population declines due to forest succession and habitat loss, its evolutionary toolkit suggests a bird well-equipped to persist. The timberdoodle may be quirky, but it’s also resilient—and that may be the key to its long-term survival.

Sage Marshall is a longtime outdoor journalist from southwest Colorado. He has lived across the U.S. and currently resides in Western Montana, where he explores the rivers and mountains around Missoula with his partner, Bela, and their adopted bird dog, Gunney. He is a contributing writer and former editor for Field & Stream. His work has also been featured in nationally renowned publications such as Outdoor Life, Men's Journal, and Westword. He is the author of the poetry collection Echolocation (Middle Creek Publishing).

Itinerant breeding is very interesting and confusing. If the female has a successful nest, i.e. chicks survive predation, do the females continue their migration – and, at what point?