Home » Firearms and Shooting » Shotguns » From the Invention of Gunpowder to the First Shotgun Cartridges

From the Invention of Gunpowder to the First Shotgun Cartridges

Project Upland is an editorial initiative to capture the cultures…

The invention of gunpowder served as the catalyst to develop the firearms we use to hunt today as well as the development of our hunting dogs

Recently, while listening to the Hunting Dog Confidential Podcast on the Origins of Pointing Dogs, I gained new insight into how pointing dogs and the development of firearms were so tightly connected. To put it simply, the need for a pointing dog came about because we gained a new weapon to kill our game. But well before we transitioned from nets, crossbows, and falconry as our means of hunting wild birds, this whole revolution required the invention of gunpowder.

The earliest recorded reference of gunpowder was in the Taishang Shengzu Jindan Mijue during the Tang Dynasty in China; it was discovered during an alchemist’s search to find an elixir of life. (Cambridge University Press 2008) It would still be hundreds of years until gunpowder would begin to be harnessed in way that resembles a more modern firearm.

Craig Koshyk, Editor-in-Chief of Hunting Dog Confidential and foremost authority on hunting dog history and development, inspired me to dig into old books to find the clues that lead to the stories of our past. One such book is The Gun and Its Development, written by W. W. Greener in 1897. In the second chapter of this historic text, Greener lays out the oldest historic references to the development and use of gunpowder. He references the invention of gunpowder in China as early as the 9th century, but leans heavily into discussing its development in Europe as it was harnessed for the refinement of the modern firearm and, more specifically, for the breech-loader.

What follows is a collection of excerpts from The Gun and Its Development by W. W. Greener, 1897.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION for FREE Google | Apple | Spotify

The invention of gunpowder

There seems little doubt that the composition of gunpowder has been known in the East from times of dimmest antiquity. The Chinese and Hindus contemporary with Moses are thought to have known of even the more recondite properties of the compound. The Gentoo code, which, if not as old as was first declared, was certainly compiled long before the Christian era, contains the following passage:

“The magistrate shall not make war with any deceitful machine, or with poisoned weapons, or with cannons or guns, or any kind of fire-arms, nor shall he slay in war any person born an eunuch, nor any person who, putting his arms together, supplicates for quarter, nor any person who has no means of escape.”

Gunpowder has been known in India and China far beyond all periods of investigation; and if this account be considered true, it is very possible that Alexander the Great did absolutely meet with fire-weapons in India, which a passage in Quintus Curtius seems to indicate. There are many ancient Indian and Chinese words signifying weapons of fire, heaven’s-thunder, devouring-fire, ball containing terrestrial fire, and such-like expressions.

Dutens in his work gives a most remarkable quotation from the life of Apollonius Tyanseus, written by Philostratus, which, if true, proves that Alexander’s conquests in India were arrested by the use of gunpowder. This oft-cited paragraph is deserving of further repetition:

“These truly wise men (the Oxydracas) dwell between the rivers of Hyphasis and Ganges. Their country Alexander never entered, deterred not by fear of the inhabitants, but, as I suppose, by religious motives, for had he passed the Hyphasis he might doubtless have made himself master of all the country round them; but their cities he never could have taken, though he had led a thousand as brave as Achilles, or three thousand such as Ajax, to the assault; for they come not out to the field to fight those who attack them, but these holy men, beloved of the gods, overthrew their enemies with tempests and thunderbolts shot from their walls. It is said that the Egyptian Hercules and Bacchus, when they invaded India, invaded this people also, and, having prepared warlike engines, attempted to conquer them; they in the meantime made no show of resistance, appearing perfectly quiet and secure, but upon the enemy’s near approach they were repulsed with storms of lightning and thunderbolts hurled upon them from above.”

Although Philostratus is not considered the most veracious of ancient authors, other evidence corroborates the truth of this account, and it is now generally acknowledged that the ancient Hindus possessed a knowledge of gunpowder making. They made great use of explosives, including gunpowder, in pyrotechnical displays, and it is not improbable that they may have discovered (perhaps accidentally) the most recondite of its properties, that of projecting heavy bodies, and practically applied the discovery by inventing and using cannons. The most ingenious theory respecting the invention of gunpowder is that of the late Henry Wilkinson.

“It has always appeared to me highly probable that the first discovery of gunpowder might originate from the primeval method of cooking food by means of wood fires on a soil strongly impregnated with nitre, as it is in many parts of India and China. It is certain that from the moment when the aborigines of these countries ceased to devour their food in a crude state, recourse must have been had to such means of preparing it; and when the fires became extinguished some portions of the wood partially converted into charcoal would remain, thus accidentally bringing into contact two of the principal and most active ingredients of this composition under such circumstances as could hardly fail to produce some slight deflagration whenever fires were rekindled on the same spot. It is certain that such a combination of favorable circumstances might lead to the discovery, although the period of its application to any useful purpose may be very remote from that of its origin.”

The introduction of explosives into Europe followed the Mahomedan invasion. Greek fire, into the composition of which nitre and sulphur entered, was used prior to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. In 275 a.d. Julius Africanus mentions “shooting powder.” Gunpowder, or some mixture closely resembling it, was used at the siege of Constantinople in 668. The Arabs or Saracens are reputed to have used it at the siege of Mecca in 690; some writers even affirm that it was known to Maiiomet. Marcus Grscus described in Liber ignium an explosive composed of six parts saltpeter and two parts each of charcoal and sulphur. The manuscript copy of this author in the National Library at Paris is said to be of much later date than 846, inscribed upon it; the recipe given is nearly akin to the formula still employed for mixing the ingredients of gunpowder.

Other early uses of gunpowder recorded are: by the Saracens at Thessalonica in 904; by Solomon, King of Hungary, at the siege of Belgrade, 1073; in a sea conflict between the Greeks and Pisanians, the former had fire-tubes fixed at the prows of their boats (1098), and in 1147 the Arabs used fire-arms against the Iberians. In 1218 there was artillery at Toulouse. In the Escurial collection there is a treatise on gunpowder, written, it is supposed, in 1249, and it is from this treatise that Roger Bacon is presumed to have obtained his knowledge of gunpowder; he died in 1292, and the description is contained in a posthumous work, De nullitate, etc., which was probably written in 1269.

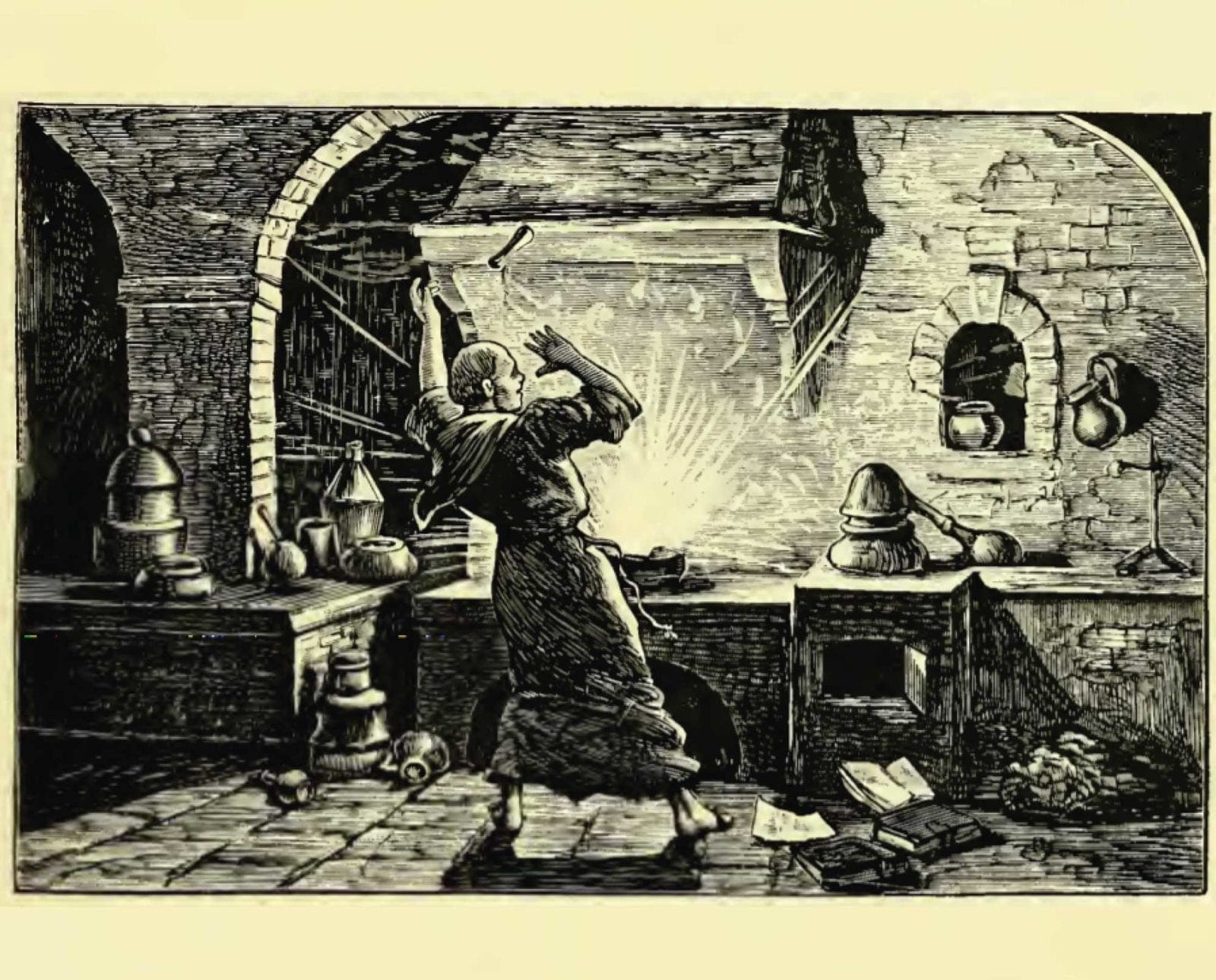

Berthold Schwartz, a monk of Friburg, in Germany, studied the writings of Bacon regarding explosives, and manufactured gunpowder whilst experimenting. He has commonly been credited as the inventor, and at any rate the honour is due to him for making known some properties of gunpowder; its adoption in Central Europe quickly followed his announcement, which is supposed to have taken place about 1320. It is probable that gunpowder was well known in Spain and Greece many years prior to its being used in Central and Northern Europe.

In England gunpowder does not appear to have been made or bought until the fourteenth century. The ingredients were usually separately purchased and mixed when required. Mr. Olliver, of Boklersberry, appears to have been one of the first dealers in explosives; for many years after the use of gunpowder had become general in war the quantities required were purchased abroad, and royal presents to the reigning sovereigns of England often included a barrel or more of gunpowder. Its manufacture in England, as an industry, dates back to the reign of Elizabeth, when mills were first established in Kent, and the monopoly conferred upon the Evelyn family.

As to what was known of the origin of gunpowder by authorities living prior to the Commonwealth, the following extract from Robert Norton’s Gunner, published in 1628, shows exactly.

“I hold it needeful for compiling of the whole worke as compleate as I can, to declare by whom and how this so dieullish an invention was first brought to light. Vffano reporteth, that the invention and vse as well of Ordnances as of Gunnepowder, was in the 85 yeere of our Lord, made knowe and practized in the great and ingenious Kingdom of China, and that in the Maratym Provinces thereof there yet remaine certaine Peeces of Ordnance, both of Iron and Biasse, with the memory of their yeeres of Foundings ingraued upon them, and the Arms of King Fiiey, who, he saith, was their inventor. And it well appearethe also in ancient and credible Historyes that the said King Vitey was a great Enchanter and Nigromancer, whom one Sune (being vexed with cruell warres by the Tartarians) coniured an euill spirit that shewed him the vse and making of Giinnes and Poti’der ; the which hee put in Warlike practise in the Realme of Ffgu, and in the conquest of the East Indies, and thereby quieted the Tartars. The same being confirmed by certain Portingales that have trauelled and Nauigated those quarters, and also affirmed by a letter sent from Captain Artred, written to the King of Spaine, wherein recounting very diligently all the particulars of Chyna, sayd, that they long since used there both Ordnance and Powder; and affirming farther that there hee found ancient ill shapen pieces, and that those of later Foundings are of farre better fashion and metall than their ancient were.”

What is gunpowder?

Gunpowder, by definition, is an explosive and is regulated by the ATF in the United States . Most modern hunters know two distinct types: black powder and smokeless powder.

W. W. Greener wrote about the definition of gunpowder as follows:

Explosives may be divided into three chief classes; first, simple substances which are of themselves explosive, such as picric acid and its alkaline salts, and the fulminates of silver and of mercury ; second, mechanical compounds of various substances not of themselves explosive, such as chlorate of potassium with sugar, saltpeter with charcoal and sulphur; third, chemical compounds, such as nitro-glycerine and nitro-cellulose. Sometimes the chemical compounds of the last division are used as ingredients in a mechanical compound (as, nitro-glycerine with kieselgurh to form dynamite). . .

To the second division gunpowder belongs. This explosive was until recently the only one in general use, the only one the legislature needed to recognize. Other mechanical compounds (as chlorate of potassium with sugar and flour) constitute explosives which are not nearly so stable as ordinary gunpowder, of greater strength, but in no degree trustworthy.”

Note on the history of cartridges, by W. W. Greener

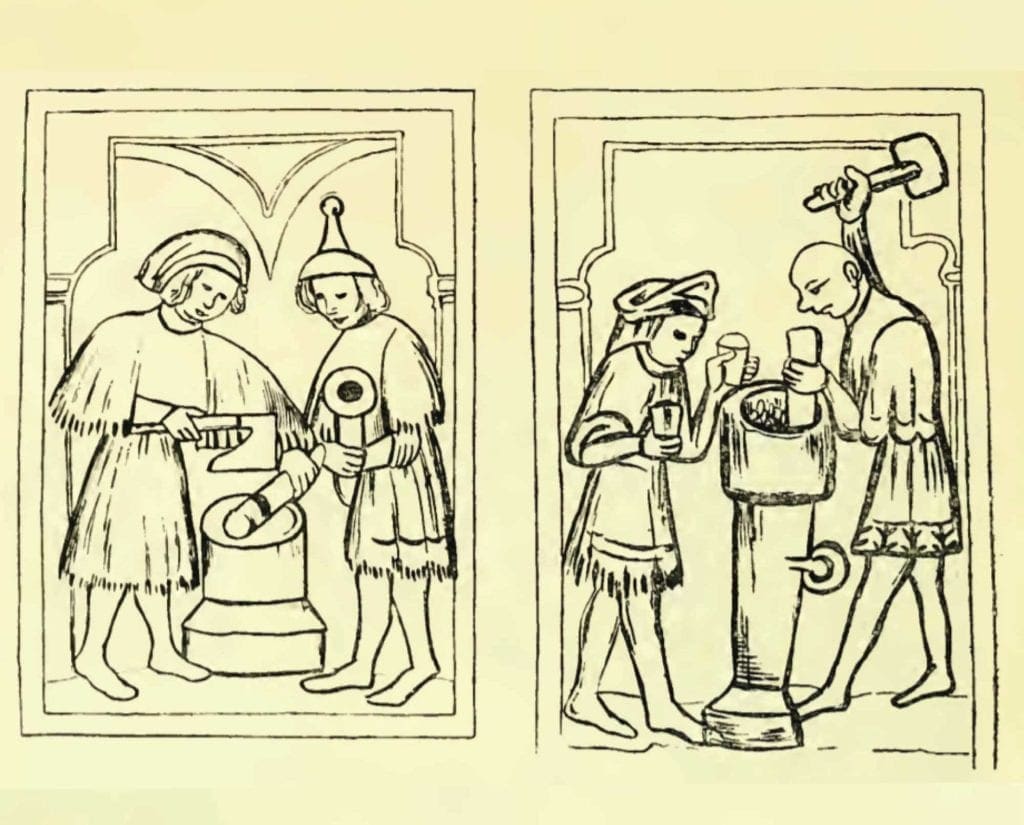

The first cartridges were merely charges of powder wrapped up separately to enable the shooter to load more quickly, and dispense with the cumbrous powder horn. Capo Bianco, writing in 1597, states that cartridges had long been in use among Neapolitan soldiers. Other authorities state that the troops of Christian I. were the first to use cartridges, and they fix the date as 1586. In the Dresden Museum there are Patronenstocke and other evidence to fix the use of cartridges so early as 1591, and doubtless throughout the seventeenth century their use became general.

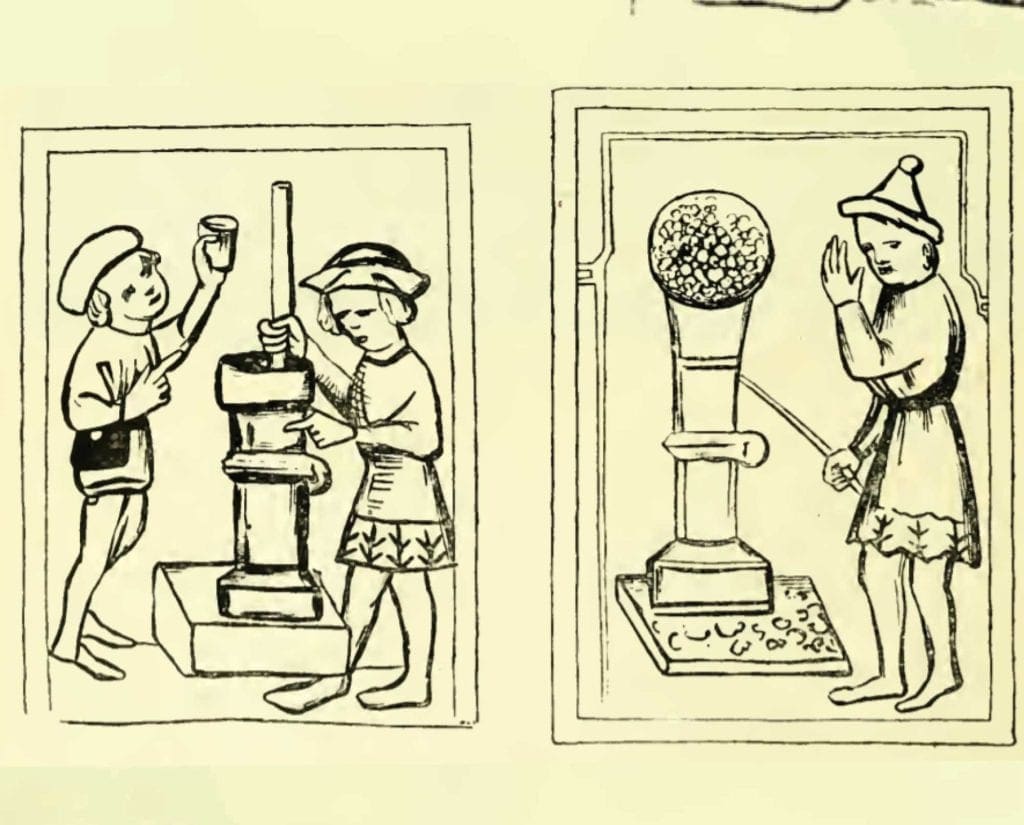

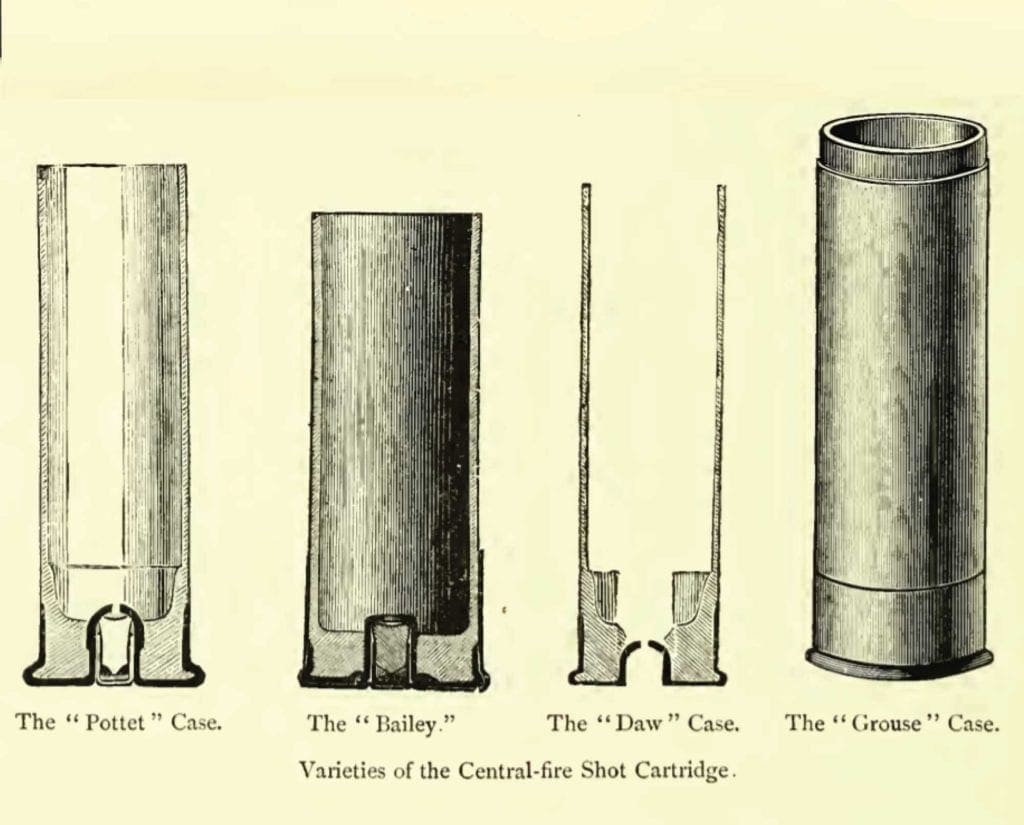

The first mention of cartridges in the records of the British Patent Office is in 1777, when William Rawle patented several “instruments for carrying soldiers’ cartridges,” which consisted of cartridge boxes having numerous divisions. The military cartridges were tied round at each end with string, and the end that contained the powder had to be bitten off and the powder poured down the barrel, and the bullet and paper rammed down, the paper thus serving as a wad or patch. In 1827 a patent was obtained for a wire-shot cartridge by Joshua Jenour ; the cartridge was made from woven wire, with meshes so wide as to allow the shot to be scattered. In 1828 Edward Orson patented a shot cartridge made in two parts, so that the powder might be easily separated from the shot, cases made to break on issuing from the barrel, and so scatter the shots. Augustus Demondion in 1831 patented a breech-loader and cartridge for the same. The cartridge had a tube containing detonating powder projecting from its base. It was exploded by a hammer attached to the end of the mainspring, and striking upwards. Another cartridge was patented in the same year by the Marquis of Clanricarde.

The cartridge consisted of many sections of a cylinder so united as to form a cylinder. These were intended to be scattered when fired, and the barrel was made bell-mouthed for that purpose. In 1831 a similar cartridge to that used in the Prussian needle-gun was patented in England by Abraham Adolphe Moser; this cartridge had the detonating powder attached to the wad placed between the bullet and in front of the powder. This cartridge was first used in a needle-gun loaded from the muzzle, the breech-loading needle-gun not being invented till 1838.

M. Lefaucheux in 1836 produced a breech-loading gun and cartridge. The cartridge as shown is of paper with a metal base; the cap was placed in a chamber with its cup end pointing upwards. A loose brass rod projected from the cup of the caps upwards through the cartridge case, and was struck by the hammer and driven down into the cap, thus causing the discharge. From this cartridge may be dated the success of the modern breech-loader: for, by the expanding at the moment of discharge, escape of gas at the breech is rendered impossible: though, if not well made, or if heavily loaded, they, in common with all pin-fire cartridges, will burst at the pinhole and allow an escape of gas through it. The cartridge as used by Lefaucheux is still the same as that now commonly supplied for pin-fire guns.

Where gunpowder takes us from here

The relevance of gunpowder and its application to the hunting world came to fruition at the most recognizable level with the invention of the breechloader. The breechloader would take us from the first hammered double guns to the eventual “hammerless” shotguns that we love today. The name Lefaucheux, now very much lost to history, is really where the final act lies in the leap to the shotguns and shot shells we use today.

The modern state of gunpowder and the cartridges we use has advanced in many ways since the turn of the century. Modern ballistics have allowed us to push the limits of accuracy and shot patterns, even though many of these advances aren’t immediately obvious since the shotguns and loads we use don’t look very different from those shown in images of days gone by.

Project Upland is an editorial initiative to capture the cultures and traditions of upland bird hunting. We seek to inspire a future generation of upland bird hunters to understand the essence of hunting traditions and the critical cause for conservation.