Home » Hunting Dogs » The Long-Coated St. John’s Water Dog

The Long-Coated St. John’s Water Dog

Scottie Westfall is a native West Virginian who now lives…

Tracing the origins of Flat-coated and Golden Retrievers through the extinct dog breed, the Long-Coated St. John’s Water Dog

The history of retrievers is very recent when compared to other types of dogs, and in the case of those bred by noble families in the British Isles, much of the origin is well-documented. The Labrador Retriever is well-known to have derived from the St. John’s Water Dog, a working fisherman’s dog that hauled in lines, nets, and even stunned fish from the boisterous, chilly seas of Newfoundland’s Grand Banks. Some texts call this dog a “lesser Newfoundland” or “true Newfoundland” to differentiate between this smaller dog and the large Newfoundlands that were all the rage as pets during the nineteenth century. A few texts called them “Labradors,” which leads to great confusion. The modern Labrador Retriever came into being in the 1880s when the Duke of Buccleuch included dogs from the Earl of Malmesbury in his breeding program.

Listen to more articles on Apple | Google | Spotify | Audible

The last of the St. John’s Water Dogs were living in Newfoundland in the late 1970s. They were smooth-coated and mostly black, and it was easy to see how such dogs could have been selected into the modern Labrador Retriever in Britain.

All retrievers derive from this working fisherman’s dog. Much of the speculation in discussions of retriever origin is really about how this working dog developed, and Labrador Retriever historians have very clearly posited their dog as a derivative of the St. John’s Water Dog. Golden Retrievers and Flat-coated Retrievers, which were similarly derived from the St. John’s breed, are not as well-defined as being from the same stock. But they clearly were, and they were bred by people with the same socioeconomic status as those who created the Labrador.

The Labrador’s smooth coat connects it to the most recently surviving St. John’s Water Dogs, but the Golden and Flat-coated retrievers have long hair. Most historians have assumed that the long coat came from crossing the smooth-coated St. John’s Water Dog with some sort of setter, and there definitely is some evidence that setters were crossed into what eventually became the Flat-coated and Golden Retrievers. However, truly smooth-coated retrievers were quite uncommon in Britain. Almost all of them were owned by the families associated with the Earls of Malmesbury and the Dukes of Buccleuch, and these dogs were the basis of the modern Labrador Retriever breed.

The Wavy-coated Retriever, as it was known in Britain, was the most common breed of sporting retriever in Britain and Ireland during the nineteenth century. It was the first breed to be established as a popular show dog, and it had two important patrons, Sewallis E. Shirley and Dr. Bond Moore. Sewallis Shirley was the founding president of the Kennel Club and Dr. Bond Moore also had an established breeding program. Both were said to base their dogs on imported ship’s dog that were free of any cross-breeding with setters, and both produced dogs with long coats.

If they were producing long-coated retrievers that were free of setter blood, where did the long coat come from? Long hair in dogs is conferred via a recessive allele. A first cross between a setter and a short-haired St. John’s Water Dog would produce smooth-coated puppies. It would have been nearly impossible to get rid of smooth-coated retrievers in the general British population in the nineteenth century. However, they were quite rare.

Labrador Retriever historians, such as Helen Warwick and Richard Wolters, generally pointed to the setter crosses for the origin of the long-coated retrievers, but they were simply far too common to have arisen by occasional smooth-coated water dog/setter crosses.

A more careful reading of the breed history shows that at least some of the St. John’s Water Dogs imported to Great Britain had long coats.

The earliest account of the water dog from Newfoundland being used as a retriever is from Col. Peter Hawker’s Instructions to Young Sportsmen in 1814. Hawker was a celebrated shooter and a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. He recommended the “true Newfoundland” as the best retriever, which he describes as being “scarcely bigger than a pointer.” He describes the coat as “short or smooth,” a phrase that could mean that some with “smooth coats” were actually long-haired but had no wave to them. Hawker included an image of one of his “Newfoundlands” fetching a flock of Brant geese and swans. The dog’s tail can be seen sticking above the surface of the water, which Labrador Retriever historian Helen Warwick claimed was a good example of an otter tail. When I look upon the tail, though, I see a plume tail, suggesting that the dog was long-haired.

In 1822, William Epps Cormack crossed Newfoundland in search of the surviving Beothuk people. He became the first person of European descent to see the interior of Newfoundland. He makes mention of the water dogs in his account of his journey, pointing out that the “short-haired dog is preferred because in frosty weather, the long-haired kind become encumbered with ice on coming out of water.”

The exact same claim is made by Lambert de Boilieu in his Recollections of Labrador Life in 1861. Boilieu had been a mercantile agent in Labrador in the 1850s, where St. John’s Water Dogs were used as retrievers to procure fish and wild game. He claimed “the dogs sent to England with rough, shaggy coats are useless on the coast; the true-bred and serviceable dog having smooth, short hair, very smooth and close to the body.”

The period from the 1820s to the 1860s is very important for the development of retrievers in Britain, and we have evidence that in Newfoundland, long-coated dogs were not preferred for working water dogs. It is very likely that they were very keen to see these long-coated dogs sent to Britain, where they could be purchased by sportsmen to be bred into retrievers. The British shooting sportsmen were mostly wealthy, and much of their shooting was very ritualized and stylized. Their setters and spaniels had to be beautiful and stylish, and a short-coated dog just would not have been considered as fancy.

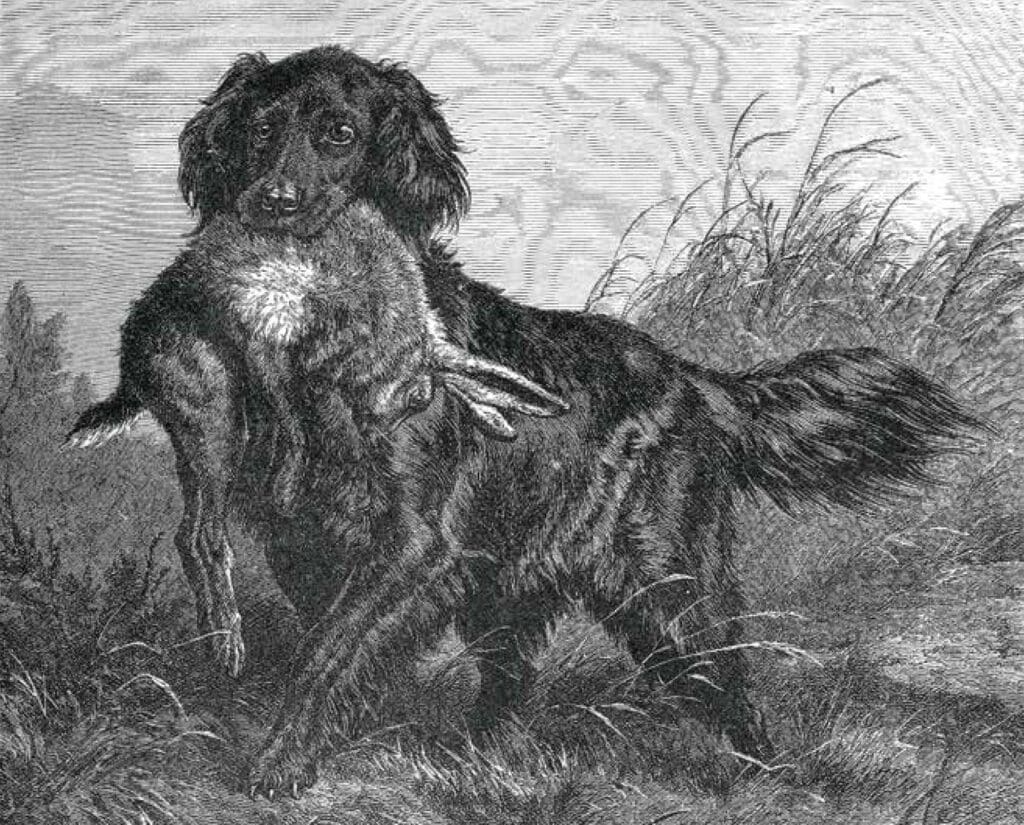

So, the Newfoundland fishermen wanted to get rid of their long-coated dogs, and the British sportsmen wanted them. One particular long-coated St. John’s Water Dog was Tip, imported by Mr. John Cotes in 1832. An image of Tip appears in George T. Teasdale-Buckell’s Complete English Wing Shot in 1907. The dog looks very much like a black retriever with some white on his chest. The dog has a long coat, though not profusely feathered. Teasdale-Buckell includes images of his descendants, both solid black, flat-coated retrievers named “Monk” and “Pitchford Marshall.”

Another more well-known dog that was descended from imports and was said to be free of setter blood was a dog simply known as Zelstone. He was owned by Mr. G. Thorpe Bartram, but his sire and dam were owned by E. G. Farquharson, who was an importer and breeder of Newfoundland dogs of all types. He lived in the county of Dorset, near the port of Poole, which was home to much of England’s fishing fleet that fished off Newfoundland. It was the city where Col. Hawker recommended going to buy a true Newfoundland and not far from Heron Court, the Earls of Malmesbury’s estate where the duck shooting was said to be excellent.

A sketch of Zelstone shows him to look very much like a black, show-bred Golden Retriever, but when he was shown as a Wavy-coated Retriever, he was noted because his coat lacked any wave to it all. This was the beginning of the transition from the Wavy-coated Retriever to the Flat-coated Retriever.

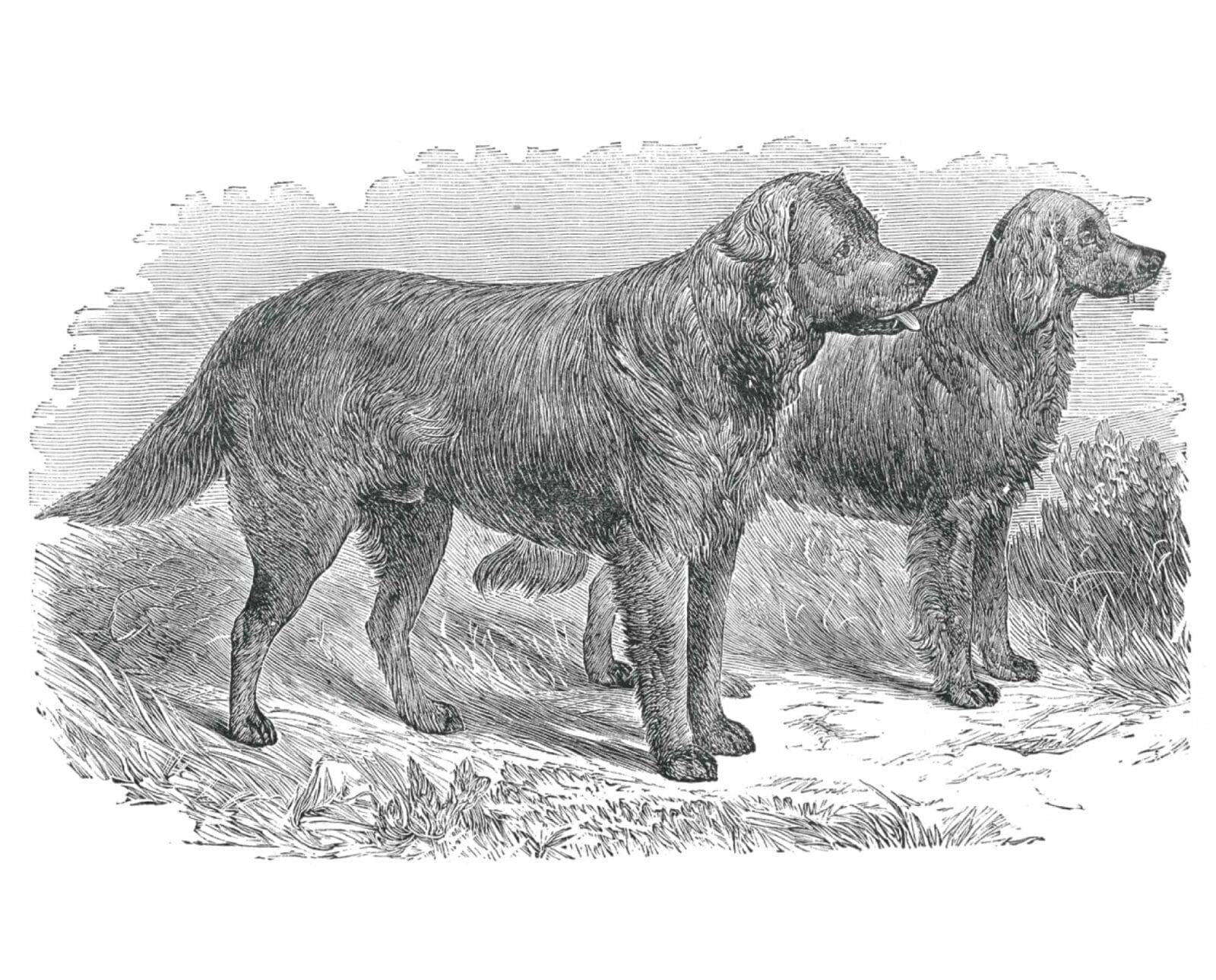

From the 1860s until the 1920s, it was common for retrievers to be crossed with other breeds. Wavy-coated Retrievers were indeed often crossed with setters, and the earliest standard of the Wavy-coated Retriever allowed for a “setter cross” as a type. The other type, which was free of setter blood, was called the “Bond Moore” type. Dr. Bond Moore of Wolverhampton was very much into creating the Wavy-coated Retriever as a fancy show dog. Dogs of his type had more bone than the setter crosses. When Stonehenge ( John Henry Wals) wrote of the two different types in his book Dogs of Great Britain, America, and Other Countries, he included an image of two Wavy-coated Retrievers. Paris was of the Bond Moore type, heavily-boned and with a broad skull and small ears. The other was Melody, and she possessed long, setter-like ears and a lighter frame.

As retriever trials developed in the early decades of the twentieth century, the lighter-built dogs were viewed as more stylish in the field. The modern Flat-coated Retriever is based on these dogs. One could be forgiven for thinking that the Flat-coated Retriever is mostly a setter-derived breed, but its ancestors were in fact St. John’s Water Dogs crossed with the Newfoundland.

Bond Moore kept his dogs free of the setter cross. He only ever used dogs that were of St. John’s Water Dog ancestry. He also believed that his Wavy-coats should by solid black in color, and when judging, he would disqualify a dog that had even a few white hairs on its chest. However, in his Illustrated Book of the Dog, Vero Shaw described “a brace” of yellow puppies that had been born to black parents at Moore’s kennels in Wolverhampton. Moore said that virtually every kennel of black Wavy-coated Retrievers that were of this type would occasionally produce yellow puppies. These puppies were born in 1876 or 1879, which would have been after the Marjoribanks family began their breeding program of yellow retrievers in the Scottish Highlands. However, this mention shows that the yellow color was in the St. John’s Water Dog, and that it popped up in British retrievers that were of that blood.

So, Golden and Flat-coated Retrievers are derived from long-coated St. John’s Water Dogs that were occasional crossed with setters and other native British breeds. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the settlers and fishermen preferred smooth-coated dogs, while the British sportsmen, always seeking something stylish, likely wanted the long-coated ones. The first wave of British retrievers derived from the St. John’s Water Dog that became popular as show and sporting dogs in the nineteenth century were long-coated. It was only in the period of retriever trials in the 1910s that the dogs we would call Labrador\ Retrievers would become common and eventually take over as the preeminent British retriever breed.

Scottie Westfall is a native West Virginian who now lives in the backwoods of Central Florida. A long-time admirer of retrievers, he writes extensively about dog history at retrieverman.wordpress.com. He is passionate about studying the significance of dogs in human culture as well as their own evolution as a domestic animal.

Always enjoy these discussions but am disappointed that Chesapeake Bay dogs were not included. The progenitors of the CBR, Sailor and Canton, were described as “Newfoundlands” in 1807, predating the Labrador by decades. The Newfoundland to Chesapeake lineage tends to be lost by the St. John’s dog to Labrador Retriever popular history. My $.02.

I agree with you on this, the CPR has far more in common with the St. John’s water dog by personality and characteristics than Labrador retrievers. Most people think this breed is extinct but in my opinion it is not, I’ve lived in Newfoundland my whole life and they’re what we call cape shore water dogs. Very similar to what was known as the St. John’s water dog but a group was sent to the an area known as the cape shore where they received this name, while there aren’t huge numbers of them they are still being bred here today, some breeders have introduced CBR to the bloodline over the years to take away the risk of inbreeding