Home » Conservation » Aldo Leopold: Wisdom of a Ruffed Grouse Hunter

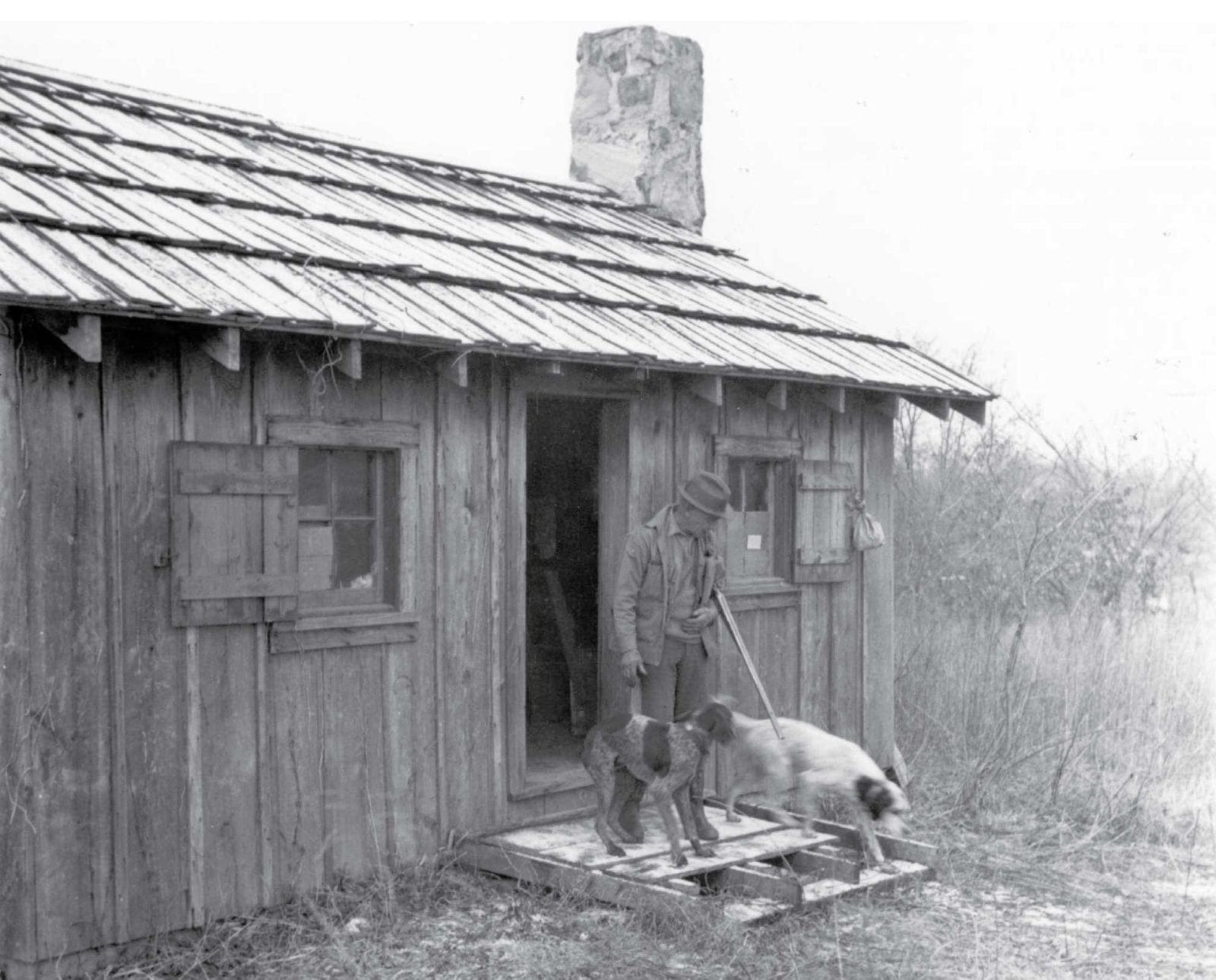

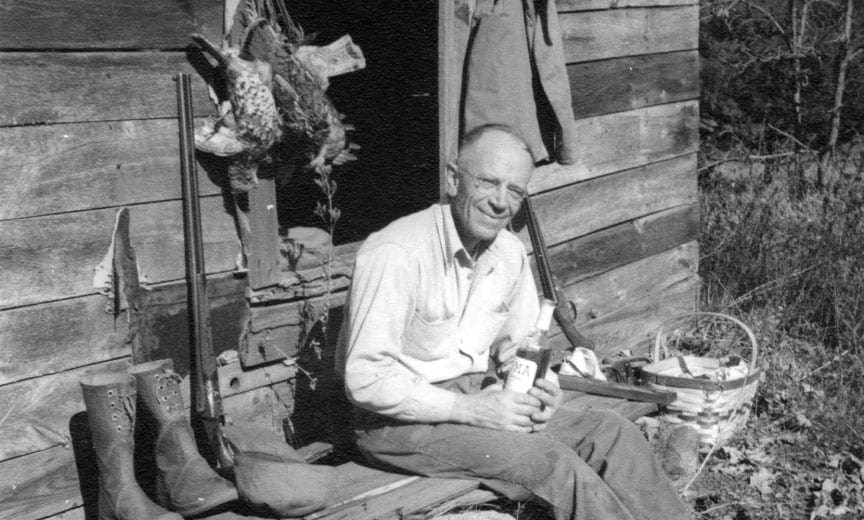

Aldo Leopold: Wisdom of a Ruffed Grouse Hunter

Understanding Aldo Leopold: a founding father of conservation and passionate ruffed grouse hunter

Aldo Leopold is considered a father of the American conservation movement. His A Sand County Almanac has influenced countless conservation scientists and nature lovers. He helped change the way our culture perceives the environment by promoting a new “land ethic” that “changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it” and “implies respect for his fellow-members and also respect for the community as such.”

It’s a testament to Leopold’s influence that this philosophy seems like common sense to us now. But Leopold was not a trained philosopher. He was a forester, and it was this professional background that helped him articulate the land ethic many conservationists now take for granted.

A Sand County Almanac was published in 1949, shortly after Leopold died while helping fight a wildfire on his neighbor’s property. This short book rings with concise but poetic prose; blunt but gentle. Here are a few lines about grouse hunting: “The dog knows what is grouseward better than you do. You will do well to follow him closely, reading from the cock of his ears the story the breeze is telling.”

Leopold is warm and welcoming, but he challenged his readers to change the way they viewed the world. “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us,” he wrote. “When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

Pioneer of responsible forestry

Leopold did not devise his conclusions about conservation in a vacuum of academic thought; formless and unempirical. He answered his own questions while in the field as a forester. Leopold graduated from the Yale School of Forestry in 1909, four years after the creation of the U.S. Forest Service led by Gifford Pinchot.

The Forest Service, in its early days, was in some ways more of a facilitator of the logging industry than a sentinel for nature. Pinchot wanted the forests under his control to “produce the largest possible amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees.” But the concept of sustaining resources, rather than exhausting them, was relatively new to a country that was used to indiscriminately cutting down trees.

The new Forest Service under Pinchot sought to channel the economic interests of the country into the careful conservation of natural resources and ensure they were passed on to future Americans rather than thoughtlessly or deliberately destroyed.

By 1913, Leopold was a supervisor with the Forest Service in New Mexico’s Carson National Forest and was entrusted with “the protection and development, through the wise use and constructive study, of the timber, water, forage, farm, recreative, game, fish, and esthetic resources of the areas” under his jurisdiction.

In a letter to the Forest Service officers at Carson, Leopold called these resources, for short, “the forest.” Leopold, even in this early stage of his development, viewed the forest as a community rather than a mere resource to be consumed. He enjoined his officers to stop and ask themselves “what will be the effect on the Forest of each separate action we take?”

Forestry for game management

Leopold believed in the power of forestry to influence the environment, and he was a proponent of using its techniques for the betterment of wildlife.

A grouse hunter, Leopold became interested in the role of forestry in game management. In a 1931 Journal of Forestry article, he wrote what sounds like an embryonic mission statement for the Ruffed Grouse Society: “Foresters are in a good position to aid the art of game management. They can evolve some mechanism for regulating the ‘kill’; control environment to enhance game; enlighten governments, private organizations and individuals in game management needs and technique; and study game on the areas they are administering and write up their observations.”

In his 1933 book Game Management, Leopold showed a forester’s understanding of cover when he wrote, “Control of game cover or food is largely a matter of understanding and controlling plant succession.” He continued, “Cover can be controlled by either speeding up or setting back the plant succession.”

Leopold understood that humans have an inevitable interaction with the land: “The landscape is a human document written upon the page of geological history.” Not only can we insert ourselves for the betterment of the land, we should. “The conservation movement is, at the very least, an assertion that these interactions between man and land are too important to be left to chance.”

Leopold’s thinking on conservation had fully matured by the time he wrote A Sand County Almanac and defined the meaning of the land ethic. Humans can use the land, but not as a brute would. He contrasted “man the conqueror versus man the biotic citizen; science the sharpener of his sword versus science the searchlight on his universe; land the slave and servant versus land the collective organism.” This is the crystallized and poetic formulation of his early observations as a young forester with the U.S. Forest Service in 1913.

A love for ruffed grouse

Aldo Leopold died twelve years before the Ruffed Grouse Society was founded in 1961. It’s not a leap to suggest he would have been an enthusiastic member had he lived to see its creation. During his life, Leopold collected articles and reports about ruffed grouse and kept them filed away. He also did his own research and kept notes and statistics on grouse habitat, population fluctuations, and food sources.

Among the notes, clippings, and correspondence in his ruffed grouse file, Leopold saved a piece called “The Why and Wherefore of the North American Ruffed Grouse Foundation.” The founder of the organization ended his plea for membership by writing, “If you want more grouse, we need you as much as you need us.” It’s unknown if Leopold joined, but, he stated in his masterpiece that “the autumn landscape in the north woods is the land, plus a red maple, plus a ruffed grouse. In terms of conventional physics, the grouse represents only a millionth of either the mass or the energy of an acre. Yet subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead.”

- Leopold, Aldo. Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings on Conservation and Ecology (LOA #238) (Library of America) (p. 4).

- McKibben, Bill (editor). American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau (Library of America) (p. 172).

- Leopold, p. 752.

- Ibid., p. 753.

- http://images.library.wisc.edu/AldoLeopold/EFacs/ALWritings/ALReprints/reference/aldoleopold.alreprints.i0001.pdf

- Leopold, Aldo. Game Management (The University of Wisconsin Press) (p. 305).

- Leopold, Aldo. Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings on Conservation and Ecology (LOA #238) (Library of America) (p. 393).

- Ibid., p. 330.

- Ibid., pp. 186-187.

- http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/aldoleopold.algamebirds2.i0004

- Leopold, Aldo. Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac & Other Writings on Conservation and Ecology (LOA #238) (Library of America) (p. 122).

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION brought to us by: ESP – Digital Hearing Protection for FREE : Google | Apple | Spotify