Home » Homesteading » Tips For Keeping Quail Year-Round

Tips For Keeping Quail Year-Round

Born and raised in southern Ontario, it wasn't until Mike…

Useful practices for raising domestic quail during all four seasons.

When I began researching domestic quail, it seemed like raising them was a seasonal affair that always ended with selling or killing your birds. Admittedly, I understood where that mindset came from. In the beginning, I adhered to it because I couldn’t really see any other way of doing things. After all, Canadian winters are very cold, and everything I read about quail indicated that these tiny little birds wouldn’t fair well in below-freezing temperatures. Why would I try to keep my quail year-round if they’d suffer all winter long?

Like many other things in life, the truth lies in the middle. Today, I keep quail all year by strategically culling them. Let me elaborate.

Year-Round Quail Keeping Requires Two Pens

I developed a way of raising my quail that works best for both the birds and myself and, in the grand scheme of things, saves me a lot of money. The result is what I call “full circle quail keeping.” My quail pay their rent and engage in a breeding cycle that replenishes their covey. Despite what you might read elsewhere, getting domestic quail to hatch eggs and raise young is possible.

My process involves having two separate pens for the birds, both of which have dual purposes. The first is the main pen. In my case, it’s an 8’x8’ square pen with enough headspace that I can comfortably stand up inside. This is where most birds spend the warmer months scratching around and living the best version of their quail lives.

The second pen is a smaller 8’x4’ pen that sits four feet tall. My quail spend the winter in this pen. Thanks to the pen’s smaller size, they are much more likely to bunch up to keep warm amongst the straw I put down for bedding. Plus, this pen holds half a dozen straw square bales that act as insulation.

Fostering Broodiness and Incubation In Domestic Quail

As I mentioned before, quail will go broody and hatch eggs. However, you must consider some very important factors as general rules of thumb.

One such rule is that your pen must be on the ground. Despite their demeanor, quail know when they’re in an above-ground pen. As a result, they will more than likely resign from broody intentions. Think of it like this: you wouldn’t expect any other ground-nesting bird to simply skip the instinctual characteristics of doing exactly what they are genetically predisposed to do . Quail are no different.

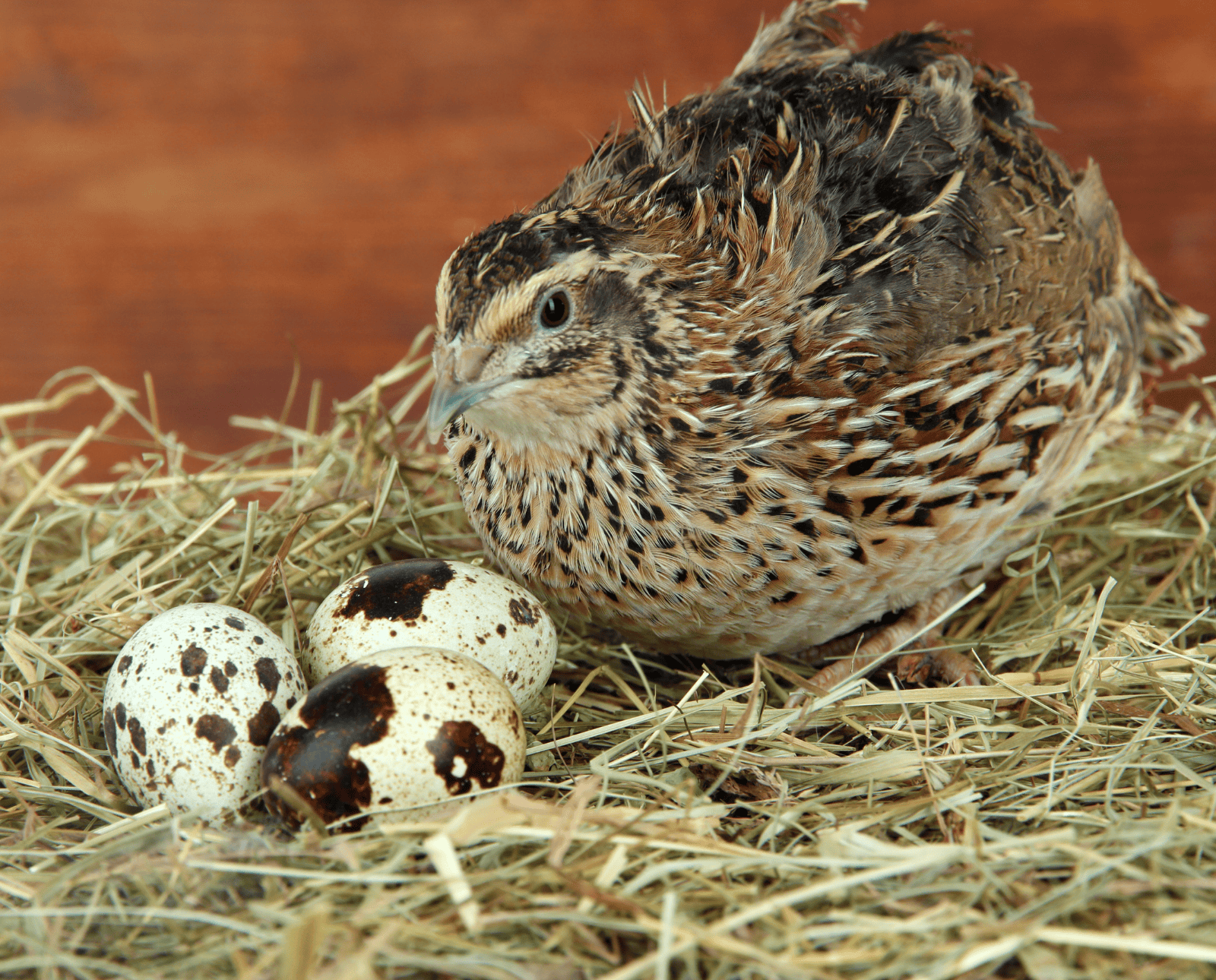

To get quail to incubate eggs, they must be on the ground, which is why my pens are ground-based. With a ratio of roughly eight hens to one rooster who will breed them, I simply stop collecting eggs when I want more quail to hatch. Instead of removing them, I place the eggs in sheltered areas ideal for a hen to go broody and set a clutch. Some hens will show interest over the course of the next couple of weeks. Others will not.

When I notice a hen staying put on a nest, I remove all other quail. Why? The other hens sometimes have a nasty habit of dining on freshly hatched chicks.

Invariably, as the chicks hatch at a decent success rate, it forces me to make room for the new birds. This usually involves culling older hens whose egg production has slowed, aggressive quail, and any males that are coming of age and will soon tip the hen-to-rooster ratio a little too far in favor of the latter.

Culling is an exceptionally important aspect of the health and well-being of a domestic covey. If you choose to, and I highly recommend you do, add your culled quail to your freezer.

Integrating Young Quail Into The Covey

So, you’ve culled birds, your hens incubated their eggs, the chicks hatched, and, miraculously, none died. You’re successfully raising quail during the entire year. Now what?

Well, it takes just six weeks for those chicks to reach maturity—I know, it happens fast. Eventually, you’ll have to incorporate those not-so-little chicks into the covey. When you do, stick around to see how the process goes. The reason is that it is not particularly uncommon for hens that seemed perfectly docile to become complete monsters. Though we may have culled the ones we were sure would be a problem, sometimes surprises happen.

Culling isn’t the only way to mitigate this, by the way. Building the pens close enough so that the birds can see each other will also acclimate them to the other group’s presence. Still, neither is a bulletproof means to get rid of all aggression. Stick around and observe your birds for a while after you first introduce the young quail into their new home.

Why Raise Quail With Varying Plumages?

My year-round quail keeping program has several different aspects, one of which includes various birds of differing plumage. This is important to me because even after the quail are dispatched, I have plans for their feathered skins. A well-skinned quail cape is a thing of beauty, and folks who tie flies for fly fishing absolutely love them. The feathers are webby, small, and mottled, perfect for several different patterns used for trout fishing.

Skinning a quail is a taxing process that takes patience, but once you’re efficient, it’s almost mechanical. The skin side will need a couple of weeks to dry and set in Borax. However, once that is done, your quail will not only have filled your belly but also give you a product that can be sold. Where I live, moving quail skins to the tune of fifteen dollars per cape makes for stock that doesn’t hang around my house for very long, especially when winter sets in and tiers are busy at their vices.

In general, keeping quail year-round can be a productive business. Between fly tiers, hunters, homesteaders, and folks who keep quail as pets, there is always a demand that quail can meet. Whether it’s their habits, their plumage, or the meat and eggs, these birds offer so much to us and ask for so little in return.

Speaking of eggs, quail eggs are remarkably delicious when pickled. In fact, I might just have a recipe!

Born and raised in southern Ontario, it wasn't until Mike was in his late twenties that he started hunting and immediately took a strong liking to the pursuit of small game. Snowshoe hare, cottontails, eastern grey squirrels, grouse, and woodcock all have a place in his heart. When not in the woods, Mike is on the water with a fly rod chasing fish with flies that I tied from the animals he's hunted. What a life!