Home » Hunting Culture » Hunting Opportunity is Not Always Equal – The Stormy Present

Hunting Opportunity is Not Always Equal – The Stormy Present

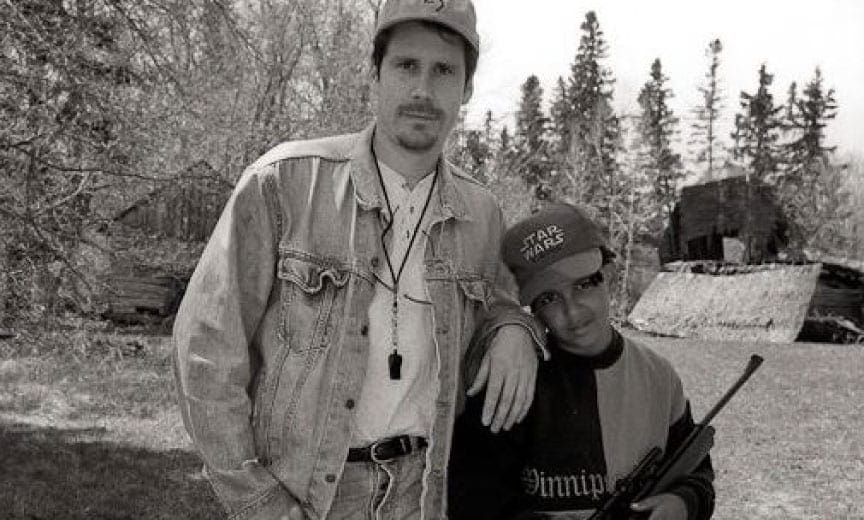

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa…

A story on how hunting privilege changes with the color of your skin.

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty and we must rise with the occasion. – Abraham Lincoln

One more sleep! I said.

Can’t wait! he replied.

It was the day before the pheasant opener. Perfect weather was in the forecast, and reports of good bird numbers were coming in from the locals. The next morning, we hopped in the truck and headed west. Then south.

Four hours later, we crossed the border. After a quick passport check and a peek at the dogs in the back, the officer waved us through. “Good luck!” he said as we pulled away.

Our next stop was to purchase shotgun shells at a big-box outdoor store an hour down the road. While browsing the gun racks, I noticed a cool looking rifle. It was a kind of gun I’d never handled before and I was curious to see what it was like, up close.

“Could I have a look at that rifle, the one on the left?”

“The AR-15? Sure, it’s used, but in excellent shape” said the guy behind the counter.

It was a sleek, well-balanced firearm that felt lighter than it looked. I shouldered it, aimed at a ceiling light. “Sweet!” I thanked the salesman and handed it back. “We’re on our way to hunt pheasants”.

“Good luck,” he replied.

We left the store and drove towards the interstate highway that would lead us to our destination, a motel in a small town in the middle of pheasant country. About a half mile from the on-ramp, I noticed blue lights flashing in my rearview mirror.

Cops.

“Good afternoon, officer.”

“Hi. I pulled you over because you have a rope or something hanging out of the back of your truck, dragging on the road.”

“Really? May I get out to have a look?”

“Yeah, step out.”

It was a check cord. It must have slipped through the space between the tailgate and bumper after we’d stopped to water the dogs. I opened the tailgate, pulled it in and put it in the drawer where it belongs. The officer checked my licence, registration and both our passports.

“Okay, guys, have a good day.”

“Thanks!” we said in unison.

Just before sundown we checked into our hotel and headed straight to a local restaurant for burgers and beers. Nothing better than mom and pop restaurant food after a long day of travelling. The next morning we drove straight to one of our favorite spots and let the dogs do their thing. By noon, we had a pair of roosters, each.

“Remember that spot we saw on our way down? We should go ask the farmer if we could hunt it.”

Twenty minutes later, after a brief chat on the doorstep of a friendly farmer’s home, we had permission to hunt about 100 acres of great looking pheasant cover. An hour after that, we were headed back to town. We’d limited out.

It’s a cool story, and in a way, perfectly ordinary.

Sure, limiting out on ring-necked pheasants is not something I actually do very often, but everything else in it reflects what, to me, is a very normal, ordinary experience as a hunter. I’ve crossed the U.S. border dozens of times, I’ve visited a ton of gun shops, I’ve been to motels, bars and restaurants all over the place and I’ve had friendly chats with a whole lot of friendly farmers. And yes, the police really did stop me once for a dangling check cord.

It’s a story of an ordinary hunt in an ordinary year. For me.

But for the other man in the story, my nephew, there is a good chance that the story wouldn’t be the same if he were alone. And it’s not because he’s younger, stronger and way more handsome than me.

It’s because he’s black.

I’m a middle-aged white man. My nephew is a young black man. Together, we’ve crossed the border, been stopped by the police, checked into a hotel, asked to see guns at a gunshop, and knocked on farmers’ doors, and we’ve never had a problem.

But what if we weren’t together? Would the story be the same? What if my nephew crossed the border in a pickup, with dogs and guns, alone? What if he asked to see an AR-15 at a gun shop, or was stopped by the police, or knocked on a farmer’s door, alone? Would the story be the same?

Before I sat down to write this piece I did a lot of soul searching, asking myself those very questions. And the answers I came up with broke my heart. And yesterday, when I asked my nephew about his experiences as a person of colour who just happens to love hunting and fishing, his answer confirmed my fears.

“I don’t really think about it much, probably because I always hunt with you and Auntie Lisa. And you guys are always the ones that ask for permission or deal with the border guards and all that. But to be perfectly honest, I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing some of those things on my own. And if my brother was with me or a couple of my black friends—no way.”

He and I are of the same blood. We have the same name—we’re Craig and Craig to our hunting friends. We grew up in the same neighbourhood, in the same city and together we’ve hunted the same coverts for over 20 years. But our experiences, as men, as hunters, as members of the upland hunting community can never really be the same.

Because the colour of our skin is not the same.

When I cross a border, knock on a farmer’s door, visit a gun shop or meet another hunter in the field, I feel no angst. Because as a white man, I’m exempt. My gender and skin colour give me an exemption from the anxieties that people of colour deal with every day. They immunize me to the effects of a virus that infects much of our world, the virus of discrimination.

But my nephew’s not exempt. He’s not immune. Because his skin is of a different colour.

Read: The Juxtaposition of Pride in Hunting

Over the last few days, I’ve heard from and read articles written by hunters of colour, of different orientations and genders and the main thing that stood out to me was that they all have to deal with a kind of angst that is completely unknown to me. The amount of angst varies of course. Some said it is mild, others admit that it is sometimes severe. But it is never zero for any of them.

Perhaps the most shocking example I read was in an article published on the MeatEater blog. Rick Dillard, a black man who loves to hunt, said: “I’ve had many black friends say there’s no way they’d go to unfamiliar places in the woods where they’d be the only black among a lot of white people they don’t know. When I go to Colorado with my friends to hunt, we’re probably the only black people on that mountain. Friends ask if I’m afraid being out there among all those white people with guns. I’m not, but it’s a real fear for many black people. It might be changing, but it’s there.”

When I mentioned the quote to my friend Durrell Smith, a young black man who’s just as crazy about bird dogs as I am, he said, “Yeah, I totally get that. When I go hunting I make sure I tell my wife exactly where I am going, who I am going with, what route we will take and when I will be back home.”

READ: Ambition to Tradition – Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club

But isn’t that what every hunter or hiker is supposed to do? I always let someone know where I’m going and when I will be back. After all, I could get lost, or my truck could break down. But for Durrell, in addition to the potential hazards of the field, he has a whole list of other things to worry about, things that never even cross my mind.

As a white man, I’m exempt. I’m spared the anxieties that people of colour deal with every day, immune to the virus of discrimination that still infects much of our world today. But Rick Dillard and Durrell Smith are not exempt. They are not immune. Because their skin is of a different shade.

As an armchair historian, whenever I sit down to write an article about dogs and hunting, I always look back to see what the past can teach us about the present. And, in this case, what we can learn is quite a lot, because much of it has been forgotten.

A few days ago A.J. DeRosa started a conversation in the Project Upland Facebook Community in which he described himself as a privileged white male. But being white and male doesn’t mean he’s automatically better off than others, or that he doesn’t have to work his ass off to succeed. It simply means that, like me, he’s exempt from the day-to-day anxieties that people of colour deal with all year round, on city streets and in the hunting field. At one point in the conversation, A.J. mentioned his grandfather, and that got me wondering if the white-male exemption has always applied to all white men. After all, A.J.’s grandfather and great grandfather were white. Were they exempt too?

One hundred twenty-five years ago in America, if your name was DeRosa, the answer would have been no. As an Italian immigrant you would have been denied the right to hunt and to own firearms and you would have faced fierce, even deadly, antipathy across the land. In fact one of the largest mass lynchings in American history was of 11 Italians in New Orleans, in 1891. Teddy Roosevelt actually described the event as “a rather good thing.”

And it wasn’t just Italians that faced discrimination. The Irish were also despised. Roosevelt wrote that “ . . . the average Catholic Irishman of first-generation as represented in this Assembly, is a low, venal, corrupt and unintelligent brute.” My Ukrainian and Icelandic ancestors faced discrimination when they first arrived in North America and Lisa’s French family can still face some resentment from some Canadians today.

But virulent anti-Catholic, Irish, Italian and French attitudes have all but vanished now. And Teddy Roosevelt is lauded—rightfully so—as a champion of conservation and ethical hunting practices. So history shows us that change is possible. The virus of discrimination can be defeated. But history also reveals that for some groups, like our black brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces, change can take centuries of painfully slow progress that only comes in fits and starts.

Yet there is hope. As millions march around the world, I believe we are on the cusp of another great change, one that will lead us to a time and place where our experiences as hunters are not coloured by the amount of pigment in our skin, but by the amount of love for the chase we hold in our hearts.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION brought to us by: ESP – Digital Hearing Protection for FREE : Google | Apple | Spotify

From their home base in Winnipeg, Craig Koshyk and Lisa Trottier travel all over hunting everything from snipe, woodcock to grouse, geese and pheasants. In the 1990s they began a quest to research, photograph, and hunt over all of the pointing breeds from continental Europe and published Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals. The follow-up to the first volume, Pointing Dogs, Volume Two, the British and Irish Breeds, is slated for release in 2020.

I would politely say that you guys are contributing to the problem by bringing up the past. I’m very disappointed in you all and in your organization. You wanna end racism? According to Morgan Freeman (the actor), one way to get rid of racism at this point in time is to “QUIT TALKING ABOUT IT”. Maybe you should follow suit. Name ONE thing in America today that a black man cannot do that a white man can.

Jackson,

Durrell Smith here. I would like to address a few of your points. First and foremost, lets talk about Morgan Freeman (and not dwell on it too long). First of all, “Freeman” as a last name denotes that he comes from slaves and his ancestors were listed as a FREE MAN during the time when Blacks were documented as such. In addition, Morgan Freeman is QUITE the talented actor and does a heck of a job narrating the Earth shows and such. Because of this opportunity, which at one point he would have had to work through the rigors and struggles of Hollywood and all. Ask Morgan Freeman, or any other Black actor what their experiences in Hollywood were and are like still. (You can also reference the Wayans Brothers who have been very vocal about upward mobility in Hollywood). I bring that up to say, Morgan Freeman is 1. only ONE voice in a much larger community, so please don’t think that he speaks for or represents all of us. I’m sure its nice to find ONE Black man that supports your argument, but Mr. Freeman is a minority…within a larger group of minorities. 2. Morgan Freeman also does not have the same issue as those of us still working to get where he is….frankly, he can choose to tune it out, much like yourself.

Now, to the bottom line…the literal bottom line of your comment. You as that we name ONE thing today that a black man cannot do that a white man can. Lets start by driving a car. Simple enough yeah? Not so…I will give you from my own personal experience, a story among many that I have told before (and do believe that I’ve got many others). At 17 years old, I was late getting to my PRIVATE, WHITE, CHRISTIAN school here in Fairburn, GA. With my little brother in the car (12 years old at the time), we put on our Landmark Christian School UNIFORMS. Let me repeat…we had identifiable evidence that we were heading to school. In order to get to school on time, I made the decision to speed, 5 miles over the limit…nothing more. With 5 miles left of my trip, we were pulled over. Now, usually, that should result in a warning, and maybe even a ticket, but it did not. It resulted in a few other things. 1. I was arrested. The cop said I was driving without insurance. At the time, my father worked (and still does) for a prominent railroad company and does VERY well in his position. Had been there many years and obviously made enough money for us to go to private school. So, needless to say, there was insurance on the car. But the cop felt compelled to arrest me. Now, lets move to problem #2…my brother, at 12 years old, was going to be left on the side of the road with no adult supervision. Thats an issue that I know you aren’t too blind to see. 3. The cop intended to tow my vehicle. 4. That puts me in a unique situation…I had to text my father (using the old school flip phone keypad) from behind my back while my little brother watched me get arrested, crying, screaming, and confused. So I was charged to make a decision…refuse to get in the cop car and stay until someone I trusted came to get my brother, OR get in, cooperate and leave him stranded. You best believe I chose to stay, AND told the officer that I would not budge until someone came to get my brother. Now….that puts me even further in the hole. Quite frankly, I could have gotten my ass kicked, charged with some bogus refusal of arrest, or Lord knows what else. So the officer then lead us to issue 5. Another officer picked my 12 year old brother up in a cop car and dropped him off at school that morning. You dropped a Black child off in a cop car at a predominately white christian private school…you tell me what message that sends. So, issue number 6…I was held in a holding cell for half the school day, and a Black clerk at the jail straight up told me that the cop was a known racist and I was not supposed to be taken to jail. I was 17. That was the FIRST of many incidents. Later, the judge was forced to drop the charges after my family hired an attorney because the cop was in the wrong.

Should I talk about the time when I worked at Albany, GA Cracker Barrel in college and a White family whose table I was assigned to would not take the glass of water that I offered them at the table, as was customary to Cracker Barrel policy? They sat and stared at me, did not speak, would not speak after I asked a number of “how can I serve you” style questions. I quickly realized what was going on, informed my manager, and they got a White server and all was well for them, as if nothing happened. This was also not during the time of COVID-19, so touching things and social distancing was not an excuse.

Would you like more?

Thank you kindly,

Durrell Smith

Minority Outdoor Alliance, Inc.

The Gun Dog Notebook, LLC

Jackson, your logic is at its best flawed. Your opinion on its best day is myopic and would never hold up in a court of law. Unless you have surveyed every person of color in the world who is living the experience of having darker skin, you literally do not have standing nor do you have enough evidence to make such a general statement. In short, you don’t know what you’re talking about. Your commentary would at least be respectful if you had said something like, “I have not personally seen or experienced racism from my perspective.” You see that cAnt be challenged Bc nobody can speak to Jackson’s life but Jackson. You can’t actually speak to an experience that you haven’t been on the receiving end of. It’s funny though Bc I can tell that the movement is impacting you, which is great! The fact that you have been moved emotionally enough to speak boldly although you are uninformed and take the public move to distance yourself from PU who has chosen as a company to support progress shows me that there is a level of engagement with the information in your mind. There is cognitive dissonance at the very least, and that’s good. Anywho, fellow human, those who choose to grow and move forward will do so…you will grow at your own pace and that is your prerogative. The sympathy I have for you is that in 50 years, your public stance will look so silly, unstudied, generalized, and quite frankly on the wrong side of the progression of the collective consciousness. Sidenote: did you catch president trump retweeting a video with white people yelling white power? Do you think those White people In that video think racism exists? Or how about when I was in law school and I was walking to class and someone yelled the n-word at me? Anywho, Jackson Good luck buddy! Summary of your very simple lesson: just because you haven’t seen something or experienced something does not mean that it doesn’t exists. Thanks for listening.

Thank you for your comments Durrell and Ashley. It is important that we share our stories and do our best to listen to each other.

Jackson, as mentioned, before I commented again, I wanted to reach out to some of my black friends to see what their answers would be to your question: “Name ONE thing in America today that a black man cannot do that a white man can.”

So yesterday I did just that, a gave them a call (I also included one native canadian since we also struggle with racism up here, in particular against natives)

Here’s a summary of the insight I gained from listening to their stories.

All agreed that, technically, and in a legal sense, the answer to your question is ‘nothing’. All Americans have the same rights and can, at least in theory, do exactly the same things. And that is due to the enormous progress made over the last 150 years. The 13th, 14th and 15th amendments gave black men freedom, citizenship and a vote. Segregation in the military ended in 1948 and in schools in 1954 . In the 1980s black handlers where finally allowed to run dogs in field trials. So a lot of progress has been made, and the US is a better country for it (up here in Canada, we’ve made progress too, but still have lots of work to do).

But let’s follow Mr. Freeman’s advice and keep quiet about the past for now, because it turns out, the real discussion we need to have is about the future and what we all hope for and expect from our lives.

You see, all of the folks I reached out to told me that as soon as you move out of the past and out of ‘theory’ and into ‘the real world in practice’, the answer is ‘lots of things’. I won’t go into everything they mentioned, but most were about ‘expectations’. In other words, what I heard from them is that the one thing a black man in America cannot do that a white man can is have the same expectations about how their life will play out now and in the future.

For example one friend said, legally, a black man can marry a white woman, but he cannot expect everyone to accept it and he should probably expect some push back, or worse. Same thing with open carry. Legally, a black man is allowed to open carry where it is allowed. In practice though, he cannot expect the same reaction from law enforcement or folks that see him with his fire arm.

Another one said black folks cannot avoid having “the talk” with their kids. I actually had to look that up, I thought ‘the talk’ was about the birds and the bees. But it refers to another conversation black parents have with their kids, that white folks don’t. Sure, they probably talk about the birds and the bees too, but when their kids get to a certain age they try to explain to them how/why they may be treated differently. None of them look forward to the talk, but all of them said they got it from their parents and would also have it with their kids.

Another mentioned things like life expectancy, health treatment outcomes and illness. Black folk cannot expect to live as long as white folks, cannot expect the same percentage of good health outcomes, cannot expect the same level of care in hospital and old folks homes.

I got plenty of other examples, but they are too long and complicated to get into here, so let me just thank you once again for at least participating in this discussion. It is not an easy one to have. Questions like yours are not easy to answer and can lead us to uncomfortable places. I totally get why you quoted Mr. Freeman. I admit, I sometimes feel like the best solution is to just not talk about it.

But all the progress we’ve made, all the changes in law and policy listed above happened because people did not keep quiet. They talked about it, argued about it, heck they fought a war over it. But progress was made by not remaining silent. And changing laws and amending the constitution is great, but it is only one part of the equation. We also need to change our attitudes and amend our treatment of each other. And that cannot happen if we stay quiet.

So to return the favour, may I ask you a question? Would you be open to asking the black guys you know and hunt with to share their thoughts about the issues I raised in my article? And would you be willing to let us know what they shared with you? Maybe they agree with Mr. Freeman or maybe they think my article is a waste of time. But I am pretty sure they’d appreciate you taking the time to listen to what they have to say.

Happy Hunting!

Thank you for your comment Jackson. I am sorry that you feel disappointed, but I am happy that you took the time to voice your opinion.

I should however mention that I may not be the best person to answer your question. I’m Canadian, and I’m white. The best thing I think I could do would be to ask some of my black friends in America to see what their answers are since they would have a better understanding of the issues than I do up here.

And while I respect Morgan Freeman’s point of view and admire his talent as an actor, I can’t agree with him on this issue. I stated the same thing to a fellow who recently posted that if we quit talking about gun rights, we’d get rid of the anti-gun issue. In any case, I am glad to see that you are at least willing to participate in the discussion and to finish your comment with a question that will keep it going.

I will post another reply after I’ve heard back from some of my black friends in American and they’ve shared their point of view.

Happy hunting!

Craig Koshyk